In January 2018, the 45th president hit a new low in a closed-door meeting: “Why…

In January 2018, the 45th president hit a new low in a closed-door meeting: “Why…

In the time since Russia invaded Ukraine, a round of self-congratulation has erupted in the West. Moscow is threatening the liberal order, but in the eyes of leaders in Washington, Berlin, London, or Paris, the West has shown the world just how strong and unified it is. The scale of the sanctions package is unprecedented, they say; the idea of freedom has shown itself to be stronger than Vladimir Putin ever could have imagined; the collective spirit of the liberal order has been restored.

It is easy to get carried away in a wave of awe at what is happening in Ukraine, faced with the patriotic bravery of Ukrainians fighting for the right to be free, the Russian military’s apparent early struggles, and the West’s stronger-than-expected response. Germany has finally awakened; the European Union has risen to the occasion; the United States has rediscovered its moral and political leadership. This is a crisis that has reminded Europe how important America remains and how important Europe might yet become.

It is true that the free world has been galvanized, and the fundamental idea of the Western world—individual freedom under democratic law—is still more powerful and righteous than any of the alternatives. But amid all the backslapping, the West has yet to face up to the broader reality of this crisis. The Russian army’s shelling of Ukrainian cities does not mark the last desperate cries of an authoritarian world slowly being suffocated by the power of liberal democracy. This crisis is unlikely to signal the end of the challenge to Western supremacy at all, in fact, for this is a challenge that is of a scale and duration that Western leaders and populations have not yet faced up to.

Perhaps this crisis really has saved the West from its solipsistic pettiness and division. But the bigger picture is far more depressing, whether in the short term for Ukraine or in the long term for the Western order itself.

Many experts have pointed out that Putin might be able to win the war and take control of Ukraine, but he cannot hold on to it for long given the scale of public opposition to his attempted colonization. This is a war that is thus far going badly for Russia, and yet can get worse, perhaps even imperiling Putin’s regime itself. The Russian economy is also at risk of collapse under the weight of the assault that has been launched by the West.

Beyond these sober analyses, however, are more sweeping claims being made in Western capitals about the long-term implications of Putin’s decision and the inevitability of the West’s ultimate victory. In his State of the Union address, Joe Biden quoted approvingly from his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelensky’s speech to the European Parliament, in which Zelensky claimed “light will win over darkness.” Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, argued similarly. “The issue at the heart of this is whether power is allowed to prevail over the law,” Scholz told the Bundestag, “whether we permit Putin to turn back the clock to the 19th century and the age of the great powers.” He then added, “As democrats, as Europeans, we stand by [Ukrainians’] side—on the right side of history!”

Does light really always win over darkness, though? It can, certainly, and did on many occasions during the 20th century. But just because it triumphed in the Second World War and the Cold War does not mean it necessarily will again now or in the future, or, indeed, that this is a fair summary of history. Just because the Allies forced the unconditional surrender of Germany and Japan, and later saw the Soviet Union collapse, does not mean there is, as Scholz declared, a right side of history.

Even if Putin is “defeated, and seen to be defeated,” as Britain’s Boris Johnson said he must be, it still does not follow that light is destined to triumph in the decades ahead. A quick scan across the world suggests that even just since the turn of the 21st century, the picture is far less rosy than the rhetoric from Biden, Scholz, and others might suggest.

Right now, the world’s second-most powerful state, China, is committing genocide against its own people and dismantling the freedoms of a city of several million, but the West continues to trade with it almost as if nothing is happening. Even as Western governments busily sanction Russian oligarchs, they continue to let Saudi oligarchs buy up their companies, sports teams, and homes, despite the fact that their leader, according to U.S. intelligence, approved the butchering of a journalist in one of his embassies. In Syria, long after Barack Obama declared that Bashar al-Assad “must go” and predicted that he would, the dictator remains in power, backed by Putin. Across the Middle East and North Africa, the Arab Spring has largely petered out into a new set of brutal dictatorships, save for one or two exceptions. In Africa and Asia, Chinese and Russian influence is growing and Western influence is retreating. It may be comforting to say that Putin’s troubles in Ukraine now prove the enduring power of the old order, but it is difficult to draw that conclusion when looking at the world as a whole.

The Western conceits that history is linear and that problems always have solutions make it hard to process evidence that challenges these assumptions. Even if Putin is unable to “win” his war in Ukraine, what if, for example, he is prepared to go further than anyone imagines in suppressing the population in whatever territory he does control? Or what if he is able to take Ukraine by force, declares it part of a Greater Russia, and threatens the nuclear annihilation of Warsaw, or Budapest, or Berlin, if the West intervenes in any way in his new territory? We might have on our hands a Eurasian North Korea, but thousands of times more powerful.

Perhaps Putin is willing to pay a price for this territory that the West finds inconceivable, forcing the U.S. and Europe into a new—and hopefully cold—war. This could last for decades: In 1956, Hungary attempted to break away from Soviet rule but was repressed in brutal fashion. It did not win its freedom for another three decades.

Even this is perhaps an optimistic scenario for the world beyond Ukraine. Whether Scholz likes it or not, the West is already in an age of competition in which “power is allowed to prevail over the law.” In fact, it always has been. The law didn’t stop the Soviet Union from invading Western Europe, after all; raw American power did.

Today, the challenge is not power replacing law but power being diffused. Russia, for example, is wielding its power not just in Ukraine but across Central Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa. Chinese power today does not just stalk Taiwan but makes its presence felt worldwide. And then there are all the other states—Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia—that believe the changing balance of global power offers an opportunity to assert themselves.

In his State of the Union address, Biden argued that in the battle raging between democracy and autocracy in Ukraine, the democratic world was “rising to the moment,” revealing its hidden strength and resolve. But is this true?

Biden listed to Congress the sanctions the West had imposed on Russia, including cutting off its banks from the international financial system, choking the country’s access to technology, and seizing the property of its oligarchs. The list is impressive, and one that analysts believe could well asphyxiate the Russian economy.

Yet Western leaders should not flatter themselves just because of the paucity of prior responses: The sanctions that have been placed on Russia might be enormous compared with the meager ones rolled out over the invasions of Georgia, Crimea, and the Donbas, or over China’s genocide of its Uyghur population, but there remain significant holes in the package, through which the West’s moral and geopolitical weaknesses are all too obvious.

Today, the reality is that the Russian state is paying for its war against Ukraine with the funds it receives every day from the sale of oil and gas. Though the Biden administration is taking steps to ban the import of Russian energy, and Britain and the EU have said they will phase out or sharply reduce their dependence on it, each and every day for now, Russia receives $1.1 billion from the EU in oil and gas receipts, according to the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. In total, oil and gas revenues make up 36 percent of the Russian government’s budget, the German Marshall Fund estimates—money, of course, it is now using in a campaign to terrorize Ukraine, for which the West is sanctioning other parts of Russia’s economy. It is an utterly absurd situation, like something from a satirical novel.

In fact, it is from a satirical novel. In Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, set in World War II, an American serviceman called Milo Minderbinder creates a syndicate in which all the other servicemen have a share, buying food around the world. One day, Milo comes flying back from Madagascar, leading four German bombers filled with the syndicate’s produce. When he lands, he finds a contingent of soldiers waiting to imprison the German pilots and confiscate their planes. This sends Milo into a fury.

“Sure we are at war with them,” he says. “But the Germans are also members in good standing of the syndicate, and it’s my job to protect their rights as shareholders. Maybe they did start a war, and maybe they are killing millions of people, but they pay their bills a lot more promptly than some allies of ours I can name.”

Today, Europe’s attitude seems not too dissimilar to Milo’s: The Russians may have started a war and may be slaughtering thousands of people, which the West is fighting to stop, but Russian energy keeps European homes warm, and at a reasonable price.

On top of the short-term challenge of the war itself, there is an altogether more difficult long-term challenge to the Western order. Put bluntly, it is possible both to believe that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine will be a disaster for Russia, giving the West a much-needed shot in the arm, and to believe that the challenges the West faces from disrupting states like Russia will remain daunting in their enormity.

In some ways, the big picture remains unaltered by the blood-drenched catastrophe in Ukraine: The West faces a Chinese-Russian alliance seeking to reshape the world order, one that Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger spent so much political capital to avoid. Only now, instead of this axis being led by an autarkic and sclerotic Muscovite empire, the senior partner is a technologically sophisticated giant that is deeply integrated in the world economy. Furthermore, unlike it was during the Cold War, the United States is now unable to bear the burden of a global confrontation with both China and Russia on its own; it needs the help of partners in Asia to curtail Beijing, and greater resolve from Europe to hold off Moscow.

Yet has the West faced up to the scale of this challenge? Does it collectively even agree what the challenge is? Though there has been a sea change in European thinking toward Russia, it’s far from clear whether there is agreement across the West that a civilizational battle is being fought between East and West, between democracy and autocracy, as Biden declared. Europe has united in opposition to Russia’s invasion, but as time goes on, and Europe’s own dynamics change, Europe’s interests may well diverge from those of the U.S. (as they appear to have done over their positions toward China).

For so long, as Noah Barkin has written, Germany has pursued a policy of change through trade, a policy that is now clearly based on a fallacy but that was common wisdom across the West, to the likes of Bill Clinton and David Cameron. In reality, China took the trade but ignored the change.

Germany and others are beginning to shift away from this policy, but that should not blind the West to the challenges that change itself poses. While it is true, for instance, that the war in Ukraine has awakened the EU and its most powerful state, Germany, the bloc’s structural challenge remains the same: It is a force in world affairs without the capacity to defend its members. It remains a construct of the postwar American world, dependent on American power for its defense. Though Germany’s sharp increase in defense spending is seismic, if Europe genuinely wishes to share the burden of American global leadership, it still has much further to go. And even if it did more to share that burden, were Europe to become more powerful in the world, would it really subjugate its interests to the wider American-led West? Why should it when it has different economic interests to protect and enhance?

Whatever happens in Ukraine, it is not clear that the level of Western unity currently on display is likely to last. It is not even clear that such unity could survive another term of Donald Trump, let alone decades of parallel political development, American fatigue over defending Europe, or the need to rebalance the Western alliance to incorporate Asian powers that fear China’s rise.

If 2022 really is a pivot in Western history, like 1945 or 1989, then it is reasonable to wonder what changes we can expect to see to the way the West is structured. The end of both the Second World War and the Cold War produced a flurry of institutional reforms that shaped the new worlds that were being born. In 1951, just six years after the fall of Nazi Germany, six European states, including France and Germany, took the first step on their journey to today’s EU. In the early 1990s, following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany was united, and a single European currency was agreed. The following decade, former members of the Warsaw Pact joined the EU.

Where, then, are the modern contemporaries to the grand figures of the postwar West who brought about European integration, economic rehabilitation, and common defense against the Soviet Union? The challenges today are new, and so new institutional scaffolding is required to rebalance the Western world’s share of rights and responsibilities; to unite the liberal democratic world; to ensure its primacy over autocratic challengers. Instead, Western leaders talk about the reinvigoration of the institutions designed in the aftermath of the last world war to ensure a new one did not begin. That war has gone. A new one is being waged.

Northeast Ohio’s Cuyahoga River bisects the city of Cleveland, winding its way past parks, railyards, and downtown breweries before emptying out into Lake Erie. The waterway has come a long way since 1969, when the river’s polluted waters caught fire and brought national attention to the nascent environmental movement. Today, people fish in the river, stroll along its banks, and enjoy paddleboarding festivals. But several dozen times a year, heavy rains flood the waterway with raw sewage.

Like many older cities in the Midwest and Northeast, Cleveland’s sewer and stormwater systems are combined, and too often can’t handle the volume of water coursing through them after a heavy storm. The city is a little over halfway through an effort to upgrade this network, building tunnels to store extra wastewater deep underground. But there’s a problem, experts warn: The designs are based on decades-old rainfall estimates that do not reflect current – let alone future – climate risk.

That worries Derek Schafer, executive director of the West Creek Conservancy, a local nonprofit that aims to protect Cleveland’s watershed. “Flooding is natural,” Schafer told Grist. But now, “with a changing climate system, we have higher volumes at quicker intervals, so our systems become even more quickly inundated.”

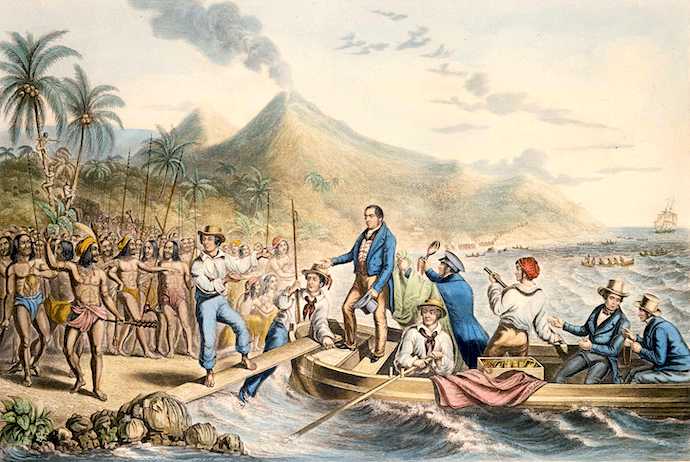

Today, combined sewer systems like Cleveland’s are found in more than 700 communities around the country. In 2004, the last year for which federal data is available, they collectively released 850 billion gallons of raw sewage into rivers, streams, and lakes — closing beaches, polluting drinking water sources, and contributing to harmful algae blooms. The Midwest is home to 43 percent of these systems, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

As of 2004, more than 700 communities around the U.S. had combined sewer systems, where wastewater and stormwater flow through the same pipes. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

As of 2004, more than 700 communities around the U.S. had combined sewer systems, where wastewater and stormwater flow through the same pipes. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection AgencySpilling large amounts of sewage into waterways is a direct violation of the Clean Water Act. And many cities, from Detroit to Chicago, have been forced to sign consent decrees with the EPA, requiring them to reduce the number of overflows by upgrading water infrastructure and capacity. This process, however, can take decades from planning, funding, and permitting to completion, said Becky Hammer, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council who focuses on federal clean water policy. That means the rainfall estimates that dozens of cities use to design their billion-dollar projects are already obsolete by the time they’re finished. The government’s own rainfall estimates are also outdated — it last released figures for Ohio, for example, in 2004 — making planning difficult even if updates were required.

Youngstown, Ohio finalized a $160 million long-term control plan for sewage overflows in 2015 based on rainfall data from the early 1980s. It’s currently in the second phase of its plan, which involves constructing a “wet-weather facility” to store and treat excess sewage and stormwater during periods of heavy rain. Indianapolis is halfway through a $2 billion tunnel project that was designed more than 20 years ago, using precipitation estimates from 1996 to 2000. Chicago is in the final stage of a nearly $4 billion effort to construct 109 miles of tunnels and three reservoirs that was designed in 1972, then updated based on modeling conducted in 2012.

Now, climate change is setting these infrastructure projects even further behind. In the decades since cities’ plans were first approved, storms in the Midwest have grown more frequent and intense. Total annual precipitation in the Great Lakes region has increased by 14 percent, according to research from scientists at the University of Michigan, and the amount of rainfall from the heaviest storms has grown by 35 percent.

A man tries to unplug a sewer drain in a suburb of Chicago following heavy rains in July 2017.

A man tries to unplug a sewer drain in a suburb of Chicago following heavy rains in July 2017.The EPA doesn’t instruct cities to consider climate change projections in their proposals, despite a report from the agency finding that “many systems could experience increases in the frequency of [sewage overflow] events beyond their design capacity.” A provision that would have required projects receiving federal funding to conduct climate change assessments was struck from the bipartisan infrastructure bill before its passage last year, Hammer said.

“There are thousands of people [with] sewage and floodwater either backing up into their homes, or running off streets into their basements, damaging property and threatening their health,” Joel Brammeier, president of the nonprofit Alliance for the Great Lakes, told Grist. It is a “failure to modernize our water infrastructure to deal with the reality that people are facing across the Midwest.”

The issue is gaining new urgency with an infusion of federal funding from November’s bipartisan infrastructure bill expected to hit state coffers in the coming months. Though cities haven’t yet figured out exactly how they’re going to use the funding or how much they’ll receive, the package includes $55 billion for water, wastewater, and stormwater management over five years. Biden’s proposed Build Back Better bill, which is currently stalled in the Senate, also includes $400 million per year directly to deal with combined sewer systems.

Cleveland started the overhaul of its water infrastructure system in 1994 under the federal Combined Sewer Overflow Control Policy, and work got underway after signing a consent decree with the EPA in 2010. The $3 billion initiative, known as Project Clean Lake, was designed using rainfall data from the early 1990s. The project’s seven new tunnels — three of which are complete, with another operational next year and three others in the construction and design phases — are built to capture most of the runoff from the “largest-volume storm” in a “typical year,” which would dump 2.3 inches of rain in 16 hours, said Doug Lopata, a program manager for the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District.

Since Cleveland began planning Project Clean Lake, however, climate impacts have gotten worse. In September 2020, Cleveland received nearly four inches of rainfall in 24 hours, the third-highest total for a single day in the city. Half of the top ten rainfall days in the city have occurred since 2000, with more than 3.5 inches of rain falling in a day in 2005, 2014, and twice in 2011. Looking ahead, more intense rainfall in the 21st century “may amplify the risk of erosion, sewage overflow, interference with transportation, and flood damage” in the Great Lakes region, Michigan researchers found.

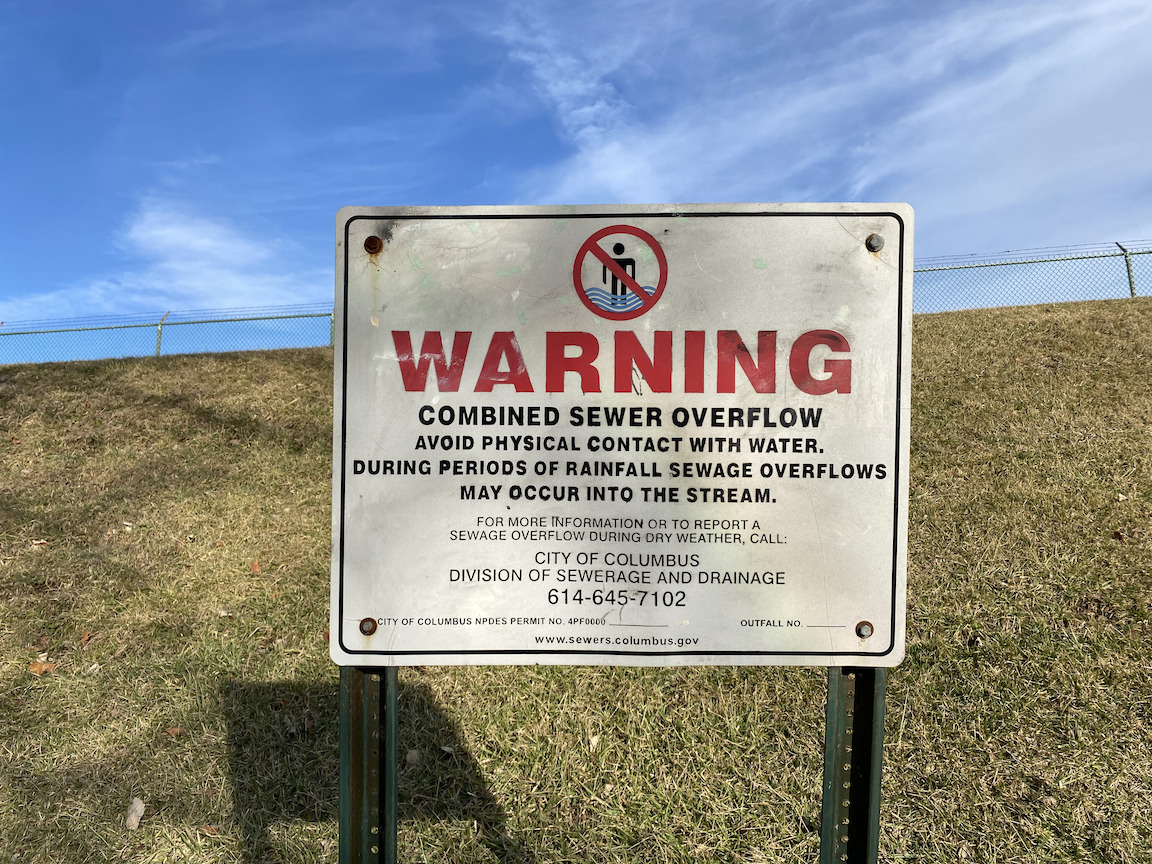

A sign warns of a combined sewer overflow, a point where sewage and rainwater discharge into the Olentangy River in Columbus, Ohio. Diana Kruzman/Grist

A sign warns of a combined sewer overflow, a point where sewage and rainwater discharge into the Olentangy River in Columbus, Ohio. Diana Kruzman/GristDespite these changes, Lopata said the sewer district isn’t planning to change the structure or design of Project Clean Lake, which aims to capture 98 percent of the water that would otherwise result in sewage overflows. Lopata believes that goal will still be achieved, even as climate change stresses the system. And even if sewage overflows aren’t eliminated entirely, he said, they’ll be reduced enough to keep the sewer system in compliance with the EPA. However, Lopata also said the district is monitoring rainfall data from the past decade and conducting an internal study to learn more about how the “typical year” has changed.

Anticipating greater and more frequent rainfall doesn’t just mean building bigger tunnels to accommodate it, though. Brammeier said cities will have to implement more of what’s known as “green infrastructure” — restoring wetlands that can absorb water and removing impervious surfaces like asphalt to reduce the amount of water that ends up in combined sewer systems in the first place. That’s going to require “a new way of thinking about doing water infrastructure at a large scale,” Brammeier said.

“You can’t build a tunnel big enough to stop the impacts of climate change,” Brammeier said. “You’ve got to think about how we’re going to make our water [infrastructure] more resilient in a more integrated way than we’ve thought about it in the past.”

Some cities are waking up to that message. Project Clean Lake includes $42 million in green infrastructure investments, and Detroit developed a 15-year green infrastructure plan to replace a tunnel project that was canceled in 2009. Milwaukee, which completed its own “deep tunnel” in 1993, now aims to eliminate sewer overflows entirely by 2035, capturing 50 million gallons of runoff with green infrastructure alone.

Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) to deal with combined sewer overflows involves building three large reservoirs to hold extra wastewater during storms.

Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) to deal with combined sewer overflows involves building three large reservoirs to hold extra wastewater during storms.While these improvements are progress, they’re likely not enough to prepare for what’s ahead, Brammeier said, and that even agencies that invest in resilient infrastructure now will need money to maintain it. Detroit’s calculations for how much rainwater the system will capture are based on data only up to 2013, and the plan states that “climate change is ignored” in this modeling. Milwaukee, which commissioned a report examining the sewer system’s vulnerability to climate change in 2014, has yet to implement many of its recommendations, according to a 2019 assessment. The city acknowledged that “continued increases in rainfall intensities and amounts” due to climate change would make it difficult to meet its rainwater-capture goal consistently.

Without significant federal aid, the costs of dealing with sewage-laced flooding are passed on to ratepayers, many of whom can’t afford to pay higher water bills in the first place. The price of water in cities like Cleveland and Chicago has more than doubled over the last decade, according to an investigation by APM Reports. Despite these increases, though, low-income communities still experience the worst consequences of aging infrastructure, Hammer said — including flooded basements from backed-up sewers. That makes funding for climate resilience in these communities all the more urgent.

“The estimates for the nationwide need for wastewater and stormwater projects is in the hundreds of billions,” Hammer said. “So we are not done.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Cities are investing billions in new sewage systems. They’re already obsolete. on Mar 8, 2022.

There are two Republican centers of gravity coming together in and around Washington D.C., and on spec, they couldn’t seem to be more different. On one side are the truckers currently engirding the D.C. metro area in an attempt to create some chrome-heeled Woodstock dystopia where everyone took the brown acid despite repeated warnings. Back in town, the ultra-conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is organizing its annual World Forum confab, which will be held this weekend down at posh Sea Island, Georgia. The event will feature a constellation of Republican leaders and deep-pocket conservative megadonors, all looking to rub their collective woes together regarding the state of political play. They would have the upcoming midterms by the throat, they fret, but for that headless orange chicken down in Florida who keeps running and running because it refuses to believe it’s already dead.

AEI and its upcoming forum have positioned themselves as vividly Not Trump. The former president was pointedly not invited to the affair, and among the key speakers will be Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who has finally made his distaste for Trump very public. Also speaking is Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, who made Trump’s all-time shit list for doing his job by certifying President Biden’s win in that state. Several other Republicans of like mind are expected to speak, and the affair may serve to formalize the expanding rift between the old-line party and its Trump-obsessed base.

Take a drive out of town and find that base in its truck convoy, however, and pumping up Trump appeared to be the last thing on most everyone’s mind. Historian Terry Bouton explored the trucker encampment at the Hagerstown Speedway, and was struck by how little politics was discussed. “Lots of Trump gear, but no one was talking about him,” he noted. “Not one person mentioned Russia or Ukraine all day.”

So what do they want? The whole trucker protest convoy idea began in Canada (funded with U.S. donations) with a fight against vaccine mandates at the border, but as mandates are rapidly going the way of the dodo, convoy organizers threw wide the doors for any and all far-right ultra-nationalist white power super-conspiracy advocates to join in, the fringe of the fringe of the fringe as it were, and the scene got weird at warp speed. Weird, and more than a little ominous.

“This was a movement-recruiting event,” reported Bouton. “It was designed to draw people in with a family-friendly, carnival atmosphere. Free food & drinks. Booths, activities, a prayer tent. Revving engines, honking horns, bright lights. ‘Sign My Truck’ with sharpies. T-shirt and flag vendors. There was a clear attempt to appear more mainstream. The focus was a big-tent ideology of ‘Freedom.’ Although started by anti-vaxxers, it was re-framed as ‘protecting our liberties’ in ways that allowed for diverse beliefs. Christian Nationalism mixed with QAnon spiritualism.”

“Christian Nationalism mixed with QAnon spiritualism” is what passes for “diverse beliefs” on the trucker circuit these days, I guess. No such wildness over at AEI, of course. Having a CEO who once worked for Democrats is about as far outside the lines as those folks tend to go. These are serious people about serious business.

“Christian Nationalism mixed with QAnon spiritualism” is what passes for “diverse beliefs” on the trucker circuit these days, I guess.

AEI, you may recall, is the birth mother of the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), another right-wing think tank that most every George W. Bush-era neo-conservative called home at one point or another roundabout the turn of the century. Their blueprint for the future, “Rebuilding America’s Defenses,” envisioned a far more militarily muscular U.S. bringing “Pax Americana” to the Middle East. All they needed was a catalyst, “a new Pearl Harbor” as they put it, and on September 11, 2001, they got exactly what they needed.

In short, this — all this, every bit of this, this ash pile we occupy, this careening juggernaut, this doomed and double-damned moment, right now — is the future PNAC and AEI set up for us 20 years ago. Soon, they’ll be down at Sea Island taking in the ocean air and plotting their next big play… and that right there is the THUD in the middle of the sentence: What play can they plan for with Trump bashing around, and with the GOP base seemingly in his grasp?

To be sure, certain high-profile GOP figures are slipping away from Trump. Mike Pence, who can easily be mistaken for a glass of low-fat milk if the prescription on your glasses is out of date, smacked Trump around at a GOP fundraiser the other day. That’s like getting attacked by a footrest.

Mitt Romney, who spends most of his time doing an excellent “Sam the Eagle from the Muppet Show” imitation, channeled some undistilled Don Rickles in his recent takedown of Trump’s most ardent allies within the party. Trump’s only response has been incoherent yelling about the fact that his precious new social media platform works almost as well as two tin cans tied together with string (and yes, these are a few of my favorite things). When Pence and Romney get bold, it’s hats over the windmill.

The Not Trumpers have their work cut out for them, because it isn’t just QAnon spiritualists flooding his corner. As recently as a week ago, a large majority of all Republicans want him to run again in 2024, preferring Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis as the nominee only if Trump stays home. Many of those still believe the big lie that Trump has been weaving for more than a year now. Much of the GOP has become like one of those bouncy rooms that gets caught in the wind and goes flying over the horizon with the kids still inside; McConnell and his ilk will need some long ropes to haul them back down to Earth.

Right now, the GOP is like a loaf of bread split down the middle. One half is stale and moldy, the other hot and filled to bursting with grubs and mealworms. The two have existed together, and even thrived, for a very long and damaging time.

The party is still mightily dangerous; even in its separated state, it is an ultimate menace. If it is repaired, the rest of us will lose badly, perhaps mortally. This bears watching.

Summer driving season is going to suck.

The backdrop of global and domestic inflation in the United States was already worrying. Now, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the global reaction to it stand to make the situation worse — including sending gas prices soaring.

The conflict has roiled global markets, causing stock market turmoil, sending oil prices higher, and injecting even more uncertainty into an already off-balance worldwide economy. It’s also sparked concerns that inflation, already running hot, could run even hotter.

In the United States, the Consumer Price Index, which measures the average change in prices consumers pay for goods and services, was up by 7.5 percent over the past year in January. That’s a 40-year high. The hope was that inflation would soon start to come down, and that factors driving it, such as high gas prices and supply chain woes, would finally pass. Now, it appears that the situation could be quite the opposite.

“What we’re observing is essentially an energy price shock and a financial markets shock that comes on the back of this already concerning inflation environment, an environment in which global supply chains are already stressed and in which there is already some degree of uncertainty as to the outlook,” said Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY-Parthenon. “It’s not just a shock in isolation, it’s a shock in that context.”

Russia is one of the biggest oil and gas producers in the world, and any disruptions stand to have a major impact on prices — disruptions we’re already seeing. On Tuesday, President Joe Biden announced that the US would ban imports of Russian oil, natural gas, and coal. The United Kingdom has said it will scrap Russian oil imports as well. These maneuvers prompted a spike in oil prices, which have already been on the rise, and the situation is sure to have ripple effects across the global economy.

In early February, JPMorgan analysts projected that disruptions to oil flows from Russia could push oil prices to $120 per barrel, which, indeed, it already has. (For context, oil was priced in the $60 per barrel range a year ago, and started 2020 in the $70s and $80s.) Some analysts have warned that worst-case scenario oil prices could hit $200, and Russia has warned that $300 oil prices could be on the horizon, depending on what Europe, which is much more reliant on Russian oil and gas than the US, does.

In the US, Russian oil made up about 3 percent of shipments in 2021, according to Bloomberg, and when you include other petroleum products, that rises to 8 percent. That’s not a ton, but it’s not nothing, either. Major oil companies, such as Shell and BP, have said they’ll stop buying oil and gas from Russia and curb business with the country, which is causing volatility and prices changes as well. Europe is starting to move away from its dependence on Russia, too.

Americans — already dealing with high gas prices and annoyed at the rising costs of heating their homes — are in for a bumpy ride. Gas prices matter not just for people filling up the tanks of their cars but also because of shipping and transportation. The conflict could also translate to high diesel prices and jet fuel for airplanes. “The inflation machine is just not going to slow down,” said Patrick De Haan, head of petroleum analysis at GasBuddy.

According to AAA, the average price of gas nationally is $4.17 a gallon, up significantly from $2.66 a year ago. That number now stands to climb even higher, especially as the summer months approach, which will put more people on the road. As the New York Times points out, the last time gas prices were so high was during the 2008 financial crisis, when — adjusted for inflation — a gallon was priced at about $5.37.

Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at accounting and consulting firm RSM, told CNN in February that the Russia-Ukraine conflict could push inflation to 10 percent year over year, driven in part by gas. By his calculation, an increase in oil prices to $110 could increase consumer prices by 2.8 percent over the course of a year. Alan Detmeister, an economist at UBS, told the New York Times that oil at $120 per barrel could mean inflation at 9 percent in the coming months.

“It becomes a question of: How long do oil prices, natural gas wholesale prices stay elevated?” he told the Times. “That’s anybody’s guess.”

In remarks at the White House on Tuesday, President Biden acknowledged that the Russia-Ukraine conflict and measures the US and Europe have taken to push back against Russia will be felt domestically. “This decision today is not without cost here at home,” he said, referring to the Russian oil ban.

The Biden administration has promised to try to protect Americans from a spike in gas prices. Over the weekend, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken told CNN that the US is “talking to our European partners and allies to look in a coordinated way that prospect of banning the import of Russian oil while making sure that there’s still an appropriate supply of oil on world markets.”

Still, the options on oil supply are limited, at least in the immediate term. “The president has insinuated that he’s got it, he’s going to do everything he can,” said De Haan in February, but it’s not clear what other strings Biden can pull on. Striking a new nuclear deal with oil producer Iran could help, but it’s no silver bullet, nor is it clear it’s very likely to happen. “It’s no Russia, in terms of oil supply,” De Haan said. The US has also begun weighing whether it could look to Venezuela.

Higher oil prices could dampen on economic growth. People and companies having to spend more on oil and gas could reduce spending in other areas, and that could cut into GDP. By one estimate, a long-term increase in gas prices could cost the typical household in the US $2,000 per year.

There are other areas where the Russia-Ukraine conflict could show up in consumer prices. Russia is the largest wheat exporter in the world. As the Times notes, Russia and Ukraine make up 30 percent of global wheat exports, and Ukraine is also a major exporter of corn, barley, and vegetable oil. Disruptions to any of that could lead to disruptions in the commodities markets, therefore pushing up prices eventually at the grocery store. The conflict has caused wheat prices to surge. Bloomberg reported in February that the Biden administration isn’t yet going to impose sanctions on Russia that would impact aluminum, which would throw a wrench in the global supply, though aluminum and metal prices have already gone up.

“It’s a combination of a set of commodities that are being produced either in Ukraine or Russia that have been affected,” Daco said. He warned that if further sanctions are imposed on Russia, it could affect aluminum and commodities prices even more. “It’s a wide spectrum of agricultural, energy, and other commodities.” On Tuesday, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree banning the exports of some commodities, which could have major global ramifications.

I took a brief moment from the news in the last hour … Big mistake.

This will have a dramatic impact on inflation, global value chains, growth and could cause a global recession. https://t.co/SP8YnMc9Q7

— Elina Ribakova (@elinaribakova) March 8, 2022

Reuters reported that the White House has warned the microchip industry about the possibility that Russia will curb access to some of the materials it sources from Ukraine and Russia and to look into diversifying the supply chain. A chip shortage and kinks in the semiconductor supply chain have contributed to higher prices and challenges across a number of industries, including cars and phones.

To be sure, there’s still plenty of uncertainty around what will happen in the Russia-Ukraine conflict and its economic consequences. Brusuelas told MarketWatch in February that the inflationary pressures depend “on the severity of sanctions and what happens on the ground.” The US and Europe have hit Russia with severe sanctions that will devastate the Russian economy and likely have a widespread impact on economic conditions around the world. In other words, economic uncertainty, including inflation, is probably not going away anytime soon.

In the United States, this will be a headache for the Federal Reserve, which is already on track to likely start to raise interest rates in an effort to combat inflation and otherwise roll back some supports for the economy.

“Energy prices mean that inflation is going to stay well above the Fed’s target in 2022, and that’s going to stiffen the Fed’s resolve to normalize monetary policy this year,” Bill Adams, chief economist for Comerica Bank, told Vox. “Inflation was drastically above the Fed’s target in 2021 and had looked like it was about to slow in 2022, but the surge in energy prices caused by the invasion is going to keep inflation higher for longer.”

Adams did, however, note that the US economy is quite strong at the moment, despite inflation. Jobs are coming back, and supply chain problems are being worked out.

“The big picture is that the US economy is strong and is well-positioned to absorb a shock like higher energy prices or disruptions to commodity supply from the Russia-Ukraine war,” he said. “We’re in a better position to absorb this shock than, for example, in 2006-2007 when energy prices were jumping but consumer balance sheets were much more stressed than they are today.”

Still, for Americans already navigating inflation, the current crisis is likely going to push prices up before they come down.

Update, March 8, 2022: This story was updated to include new economic developments stemming from the war in Ukraine.

©2025 RUPTURE.CAPITAL