Author Archive for: Rupture.Capital

Image Credit: Cynthia Briones

Image Credit: Cynthia Briones

As the Omicron variant sets record-high COVID-19 infection rates across the United States, we look at the conditions in the sprawling network of jails run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement where the Biden administration is holding more than 22,000 people. “There’s still a lot of people detained. There’s no social distancing. People are still facing COVID,” says longtime immigrant activist Maru Mora Villalpando, who adds that most COVID infections are coming from unvaccinated workers who are coming from outside of the jails. She describes how people held in GEO Group’s Northwest ICE Processing Center in Tacoma, Washington, say conditions have gotten even worse during the pandemic, after a federal judge ruled the company must pay detained people minimum wage for work like cooking and cleaning instead of paying them a dollar a day. GEO Group responded by suspending its “voluntary work program.”

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

As concerns grow about record COVID infections across the United States, we look now at conditions in the sprawling network of jails run by ICE — that’s Immigrant and Customs Enforcement — where the Biden administration is holding more than 22,000 people, who are often transferred around the country. ICE says fewer than 300 people in detention are being monitored for COVID. Rights advocates say this is surely an undercount.

Most of the ICE jails are run by private prison companies, like GEO Group, which are not transparent. In Washington state, people held in GEO Group’s Northwest ICE Processing Center say conditions have gotten even worse during the pandemic, after a federal judge ruled the company must pay detained people minimum wage for work, like cooking and cleaning, instead of paying them a dollar a day. GEO Group responded by suspending its so-called voluntary work program. On December 13th, GEO Group issued a memo at the Northwest ICE Processing Center that, quote, “no detainee is permitted to do any work previously done under the Program, including, but not limited to, work in the kitchen, the laundry areas, cutting hair, painting, waxing, or scrubbing floors, or cleaning the secure areas of the facility.”

This is Ivan Sanchez, held for more than a year at GEO Group’s ICE jail in Tacoma. In a call from inside to the group La Resistencia, he describes what happened after the federal judge ordered GEO Group to pay the detainees a living wage for their work.

IVAN SANCHEZ: We lost all our jobs and weren’t able to work anymore, so the facilities stayed dirty for about — since it lasted ’til now. They said they were going to hire a special crew to come and clean the facility, but that still hasn’t happened. And they don’t want none of us to clean. And some of the officers aren’t cleaning theirs, even though they do clean. Other than that, I’d like to say that I’ve worked for them for about three years, and I also cleaned floors in additional to that, and I did barbershop. And they wouldn’t pay me for that. So I would just get a soda or sandwiches or some chips and candy. That was it.

AMY GOODMAN: This comes as Washington state recently passed a law barring private, for-profit prison companies from contracting with agencies there, but GEO Group has signed a contract to keep its ICE jail in Tacoma open until 2025.

For more, we’re joined by Maru Mora Villalpando, the co-founder of La Resistencia and a longtime immigrant activist. In September, the government dropped its deportation case against her and granted her lawful permanent residency.

Welcome back to Democracy Now! Congratulations on your immigration status. Can you talk about why the Tacoma jail is open, and then talk about what’s happening inside with this change of what should happen to the prisoners who are also workers?

MARU MORA VILLALPANDO: Yes. Thank you. Good morning, Amy.

Yeah, what we’ve seen is that the detention center is still open. Although their contract says from 2015 that it will be open for 10 years, because that’s what the last contract was signed for, we know that every year Congress has to approve the budget for this kind of work — in this case, for detention centers to continue operating. Actually, the attorney general here in Washington filed a countersuit in September against GEO for remaining open regardless of our H.B. 1090 law. And so, according to the attorney general, for every day that they remain open, they will have to pay a fee. We assume that by next September we can actually get it shut down, because, yes, they are violating the law. Obviously, GEO filed a lawsuit — I’m sorry, an appeal to this lawsuit. And that’s what they spend the money on. They spend their money on fighting lawsuits of this kind, and they usually lose.

And in the meantime, what they decided to do was to remain — to keep people remaining detained in squalor conditions, in filth. It took over a month for GEO to actually hire an outside company. The company is called Trustus. And what we heard from people in detention is that there are some instances where about a crew of maybe two to three people show up to clean maybe for half-hour, maybe at the most an hour. And we’re talking about units that hold maybe 60 to 100 people in total. Maybe that’s not the total that we have right now in every pod. As far as we know, on December 30th, there were 411 people detained. It’s way less than the average that was 1,500 in the past, pre-pandemic. Yet there are still a lot of people detained.

There’s no social distancing. People are still facing COVID. Just from December 22 to December 30th, there were five cases of COVID in the detainee population. There were seven cases of GEO guards with COVID in that same period of time, plus three ICE employees also testing positive for COVID. So, having a crew of two to three people showing up for half-hour, maybe an hour, maybe two to three days sporadically here and there in different units, is not going to solve the problem of having unsanitary conditions.

This, the way we see it and based on what people in detention have told us, is nothing but retaliation against people detained, that thanks to their work, thanks to the hundreds of thousands of people going on hunger strike, they sounded the alarm about this exploitation. And now that Washington state passed the law against this kind of detention centers, and also a federal jury and a federal judge determined that this should not be the case and people should be paid for their labor, what GEO does is they come against people in detention, and they retaliate, and they just create further worse unsanitary conditions in the middle of a global pandemic.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Maru, I wanted to ask you — the GEO Group obviously is a national private prisons company. It has more than a hundred jails and detention centers around the country. Could you talk about what, in the lawsuit, that exposed the exploitation of people there? There was something called the sanitation memo you found, that you referred to as the hunger games? Could you explain that memo and what it signified?

MARU MORA VILLALPANDO: Yes. So, we knew, once the first hunger strikes started happening here in the detention center in Tacoma, and, really, throughout the country, that GEO has relied on the voluntary work program, which they pay a dollar a day for all this kind of work, really to create people detained as slave labor to be the backbone of the detention center.

But there’s also a part of that program that doesn’t give any money to people in detention. So, another way to make people — everyone, regardless of you choosing to go into this voluntary work program or not, everyone had to clean. That meant that every week there will be a contest, that we called the hunger game, a contest so every pod will compete against each other to see who’s the cleanest pod. And the reward was a night with the Xbox, that you can borrow, and chicken for the night, because, obviously, the food that is given to people in detention is nothing but trash. That’s another of the demands that people that have staged hunger strikes have actually named as number one. They want real food. And so, the conditions that GEO created in the first place of hunger, it’s used by pushing people to clean the units.

So, the most recent one that we saw, in early December, there were these two pods that won — C3 and A2, I believe — and, actually, one of the pods, that remained in third place, called us, and the people in that pod told us, “Well, yeah, C3 is going to win, because there’s very few people there. But if you compare to our pod, there’s way many of us here. We cannot compete against a pod that there’s less people, and they produce less trash, let’s say.”

So, this is another way in which GEO profits from not only the detention of people, but to actually make them clean, make them sustain the facility. People in detention did everything except security in the detention center. And now that GEO is saying, “No, no, they’re not going to do it,” because they refuse to pay the minimum wage, people still feel obligated to clean, because they don’t want to live in squalor, they don’t want to live in filth, and they’re afraid of the conditions in regards to COVID, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally —

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in relation —

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead, Juan.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: In relationship to COVID, you mentioned ICE has said that nine people held in its sprawling network of for-profit jails have died from COVID. What is your sense, especially with the Omicron, the spread of the Omicron variant, what is happening in terms of COVID in these detention facilities?

MARU MORA VILLALPANDO: Well, it’s spreading fast. We saw an uptick in June. We actually kept track of numbers since June. When actually the Biden administration started transferring more people throughout the country, we’ve seen an increase in detention. You know, the numbers of people detained have grown since Trump left. When Trump left, we were at 15,000 capacity; now we’re now at 21,000 throughout the nation. We even receive calls from other detention centers, such as Georgia. Yesterday, we received like five calls.

People are really worried about it, because not only it means transfers are happening and ICE doesn’t give absolutely no information about what they do in regards to COVID or anything in general, but also what we’ve seen is that guards and ICE employees might not be vaccinated. And the way we find out is because in this case in Washington, the notices that ICE has to give to the judge, the immigration judge, because there’s a lawsuit pending also in regards to COVID cases — when there’s a case, a positive case of COVID, ICE needs to notify this judge. And we get these notices. And what we can tell is that most of the guards and the ICE employees are not vaccinated; otherwise, the notice will say this person was vaccinated. And so, what people in detention have said, not only here but throughout the nation, is most of the COVID cases that we’re going to get in detention come from outside. That means all these employees that refuse to get vaccinated, they bring the COVID in, and we have no recourse, knowing also that we have suffered medical neglect for years and years in detention centers.

AMY GOODMAN: Maru Mora Villalpando, we want to thank you so much for being with us, a well-known immigrant rights activist. As we turn to Europe, where a French humanitarian group has filed a complaint against Britain and France over the drowning of 27 refugees. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “The Lost Singer” by Ismail Kaseem. The song was part of The Calais Sessions, a benefit album recorded at the Calais refugee camp with refugees and professional musicians years ago.

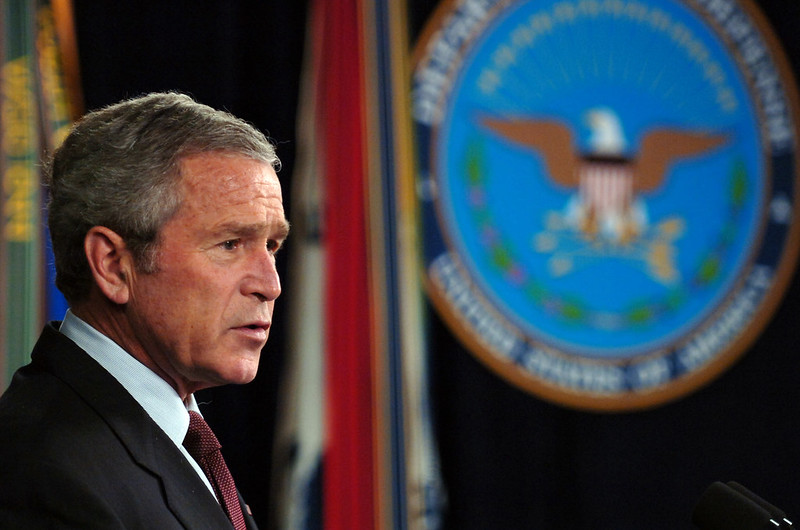

It began more than two decades ago. On September 20, 2001, President George W. Bush declared a “war on terror” and told a joint session of Congress (and the American people) that “the course of this conflict is not known, yet its outcome is certain.” If he meant a 20-year slide to defeat in Afghanistan, a proliferation of militant groups across the Greater Middle East and Africa, and a never-ending, world-spanning war that, at a minimum, has killed about 300 times the number of people murdered in America on 9/11, then give him credit. He was absolutely right. Days earlier, Congress had authorized Bush “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determine[d] planned,… Read more

Source: The War on Terror Is a Success — for Terror appeared first on TomDispatch.com.

Over the last year, since the events at the US Capitol on the 6th of January, there has been increasing scrutiny and concern around the threat of far-right extremism to and within the military. However, what is driving this threat is less clear, not only in the US but in militaries across the Western world. Therefore, it is important to consider how the hyper-masculine organizational culture promoted in the military might be creating a bridge of familiarity and appeal between service and far-right extremism.

On one side of the threat are the individuals already possessing far-right extremist belief systems that enter the military with the purpose of using their service time to gain useful skillsets or to enforce their belief systems (i.e., the opportunity to engage in sanctioned combat with an outgroup). This aligns with research indicating that others, such as organized criminal gangs, also strategically infiltrate the armed forces, in order to receive the accompanying training. This is ultimately an issue of vetting and learning to be aware of, as well as being willing to address, risk identifiers within recruits and within the culture of the ranks.

The other side of the threat comes from radicalization during or after time in service and the appeal that these groups might offer to current and former members of the forces, as well as specific targeting strategies aimed at veterans and retirees by extremists because of their skillsets. For example, there is evidence of such a strategy being employed by The Base, a US-based neo-Nazi group, seeking to appeal to veterans for their skills – they see the radicalization of ideological viewpoints as a secondary step.

The bridge between service and violent extremism is only traversed by the very few. However, these very few also have the potential to be very dangerous. Additionally, the larger the number of active and former service members that cross to non-violent extremism the higher the general threat level. While they might not pose a direct threat of violence themselves, the further extremism spreads within the ranks the sooner it reaches the level of violence.

The building blocks of this bridge are the hyper-masculine culture within which the military was formed and still operates today, offering organizational familiarities and cultural overlap for those who crave this type of environment. Western militaries were established within the international relations system – a system based on realist interpretation of the state as the sole actor, entirely masculine in nature. The male citizen both holds the power within the state, as he is the rational actor, and is willing to defend the state at all costs.

This patriarchal foundation has developed the idealized conception of the archetypal ‘hero’ as a white, straight, male figure who is brave, valiant, honorable, and patriotic. The same patriarchal organizational structure applies to most groups across the far-right spectrum, with many of the same foundational expectations of heroism twisted to extremist viewpoints.

The military training environment banks on these expectations, building the strength of the unit on absolutes – trust in authority, trust in your comrades, and the value of the mission. Boot camps and other forms of military training are designed to use extreme stress and even sometimes violence to develop the military unit in-group and formulate the strength of the hierarchal culture. Once this has been developed, a sense of loyalty lies with the in-group (i.e., the unit) and its established chain of command. A process of othering then takes place to prepare for combat, dehumanizing the enemy as a threat which needs to be neutralized. This process of becoming a soldier or “martialization” can share many parallels with the radicalization process itself, as well as with the pseudo-martial environments that many far-right organizations seek to create.

In this cultural environment, expectations of hyper-masculinity and the archetypal hero can create familiar pathways into white supremacy, ultra-nationalism, and even anti-government sentiment. The othering of the enemy is often linked to racial and ethnic profiling – in the context of the last two decades of the Global War on Terror, the Middle Eastern Muslim man – and can create a familiar pathway into white supremacy.

Patriotic, nationalist expectations of military members can be a short step from ultra-nationalist sentiment, either based on racial or ethnic hatred. On the other hand, the potential negative experience within the military – perception of failure or misjudgment, or failure to reach required goals – can be an equally short step to anti-government sentiment.

These familiar pathways are potentially encouraged by the hyper-masculinized military training and culture, often with the immediate negative impact being felt first by those within the ranks that don’t fit within this archetypal hero conception. There needs to be increased understanding at the top of how this culture is propagated within the ranks. Additionally, there needs to be further research on how transition points, into the military, potentially between ratings, and especially out of the military can be points of vulnerability and opportunity for altering mindset and action.

Transparency is needed to prevent the spread of extremism within the ranks, both on the extent of concern (e.g., details of cases or investigations into extremism) and on regulatory guidance for what is considered extremism. Ultimately, there needs to be meaningful introspection and a concerted effort to address cultural permission and encouragement of othering, through critical engagement and education at all levels. However, further education and training will only be effective if it is designed and implemented alongside transparent and meaningful analysis of the problem, not if it is only a tick-box exercise to appease the concerns of others.

Veterans should not be tainted by fears of extremism. Rather, it is essential to think about how to protect and increase resilience among active and former service members to these ideological threats. However, in order to prevent and counter the appeal of far-right extremism within the security forces, it is necessary to challenge the hyper-masculine organizational culture that is promoted and to examine how it might be creating a bridge of familiarity and appeal over the gulf between service and far-right extremism.

Dr Jessica White is a Policy and Practitioner Fellow at the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right and a Research Fellow at the Terrorism and Conflict Group, Royal United Services Institute. See full profile here.

© Jessica White. Views expressed on this website are individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR). We are pleased to share previously unpublished materials with the community under creative commons license 4.0 (Attribution-NoDerivatives).

This article was originally published at CARR’s media partner, Rantt Media. See the original article here.

Paul Dirac was one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century. A pioneer in quantum theory, which shaped...