This is the third installment of a new column by Convergence Editorial Board member Max Elbaum. “It Is Happening Here” will track the MAGA drive toward one-party rule based on a white Christian Nationalist agenda, and discuss strategies to block it while building independent progressive power along the way. Thirty years after its publication, The Age of Extremes by Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm…

Author Archive for: Rupture.Capital

Author of landmark UK review into the economic value of nature joins UN environment chief in calls for ‘action, not just words’ on biodiversity goals

Humans are exploiting nature beyond its limits, the University of Cambridge economist Prof Sir Partha Dasgupta has warned, as the UN’s environment chief calls on governments to make good on a global deal for biodiversity, six months after it was agreed.

Dasgupta, the author of a landmark review into the economic importance of nature commissioned by the UK Treasury in 2021, said it was a mistake to continue basing economic policies on the postwar boom that did not account for damage to the planet.

Vox; Getty Images

“Regime Change” sounds like a radical book. It isn’t — and that’s telling.

Patrick Deneen hates liberals. But liberals don’t hate him back.

A political theorist at Notre Dame, his 2018 book How Liberalism Failed became a surprising phenomenon among liberal elites. Despite some flaws, including a tendency toward straw-manning liberal thinkers and an allergy to empirical evidence, the book presented a thought-provoking critique of our governing philosophy from the radical right. It was a kind of Trump-adjacent conservatism liberals could engage with; Barack Obama put Why Liberalism Failed on his 2018 list of favorite books.

Last week, Deneen came out with a sequel of sorts: Regime Change, a book promising not only criticism of liberalism but a blueprint for what a “postliberal order” might look like and how America can get there. It’s a promising idea: Attacks on philosophical liberalism are common on the intellectual right nowadays, but concrete attempts to sketch what might replace a regime founded on democracy and individual rights are conspicuously absent.

Regime Change fails to deliver on this promise. All of Why Liberalism Failed’s flaws are on display in the follow-up, but in ways even more damaging to the argument. What is arguably the book’s most important claim — that liberalism is beset by an insuperable tension between a conservative mass public and an insular liberal elite — is never established with a single empirical study or even a simple piece of polling data.

The titular “regime change” similarly proves to be paper-thin. Instead of revolution and a new system of government, Deneen merely proposes replacing liberal elites with more conservative ones. And his means for doing so are mostly quotidian: policies like a universal national service program that would effectively pose little threat to existing elites.

For the most part, Deneen’s book isn’t interesting enough to be dangerous.

But the book’s failures do not render it entirely without value. It tells us something important about the intellectual right and even the culture war more broadly.

In its central conceit that America would be saved if more people in power thought like Patrick Deneen, Regime Change reveals just how much certain aspects of the culture war are really struggles between competing elites and how little relevance they have for the actual problems ordinary Americans face.

History’s worst elite?

The principal problem with liberalism, according to Deneen, is that it strips people of things that provide them with a sense of order and meaning.

By elevating individualism and progress into guiding social values, liberalism destroys the traditions and norms that allow human beings to make sense of life and find their place in the world. American Christianity is on the decline, small-town America is hollowed out, drug abuse rates are rising — all symptoms of a spiritual crisis brought on by liberalism’s philosophical assault on what Deneen sees as the sources of social stability.

The people most responsible for this state of affairs, according to Deneen, are America’s liberal “elite.”

Deneen’s definition of “elite” is somewhat broad, referring not necessarily to people with wealth or high political office, but rather “those who possess social status because they possess the requisite social and educational skills to navigate a world shorn of stabilizing norms.” He’s a bit vague on who specifically this definition applies to, but it roughly appears to mean people with college degrees working in knowledge-sector jobs: the “laptop class,” as his fellow conservatives would say.

Deneen compares this new elite unfavorably to medieval aristocrats, and even the wealthy of Gilded Age America because of their disconnection from place and tradition. Unlike aristocrats, who ruled over specific land and a specific group of peasants, the modern elite is transient and cut off from the working people who surround them. The nature of this elite, he argues, reflects “the culminating realization of liberalism”: a system that theoretically opposes hierarchy but actually has given rise to new and veiled forms of stratification.

Today’s elite care about “inequality” and “oppression,” he concedes — but only in theory. Their definitions are so airy, so focused on insular discourses surrounding race and gender, that they foster a disconnect between urban elites and their Uber drivers — let alone the working class in the countryside with whom the laptop class barely interacts. Unlike previous elites, who ruled with a sense of self-conscious noblesse oblige for those lower in the social hierarchy, the liberal elite rules only for the benefit of itself.

“The educational program of the managerial class is today intentionally designed to ensure radical disconnection from a shared cultural inheritance that might link it to lower classes,” he writes.

There is something valuable in this critique. Elite disconnect from the reality of life for the working class can foster bad or even dangerous policy ideas (see policing or welfare work requirements). And more broadly, I think Deneen is right that “traditional” social structures like houses of worship provide a sense of community and place sorely lacking in much of modern life — benefits that liberals can be too quick to dismiss.

But most of his anti-liberal broadside is at once underbaked and overheated.

The critique is underbaked in the sense that it’s not clear from his account how exactly this rather large “elite” is responsible for the destruction of conservative norms and small-town America. How can we hold a graphic designer in Chicago or a Whole Foods supply chain specialist in Austin responsible for the decline of Christian morals and the hollowing out of small towns?

It’s overheated in the sense that Deneen turns his rivals into cartoon villains, arguing that “the current ruling class is uniquely ill-equipped for reform, having become one of the worst of its kind produced in history.”

Roman nobles were legally permitted to rape their slaves. The military elites of the Mongol Empire were constantly murdering civilians and each other. In France after the Black Plague, the impoverished aristocracy stole from their already-suffering peasants to continue funding their lavish lifestyles. The elite of the early American South centered their entire society around the racist brutality of chattel slavery.

Is the American elite out of touch with the working class in ways that have tangible and negative consequences for the country? Sure. But it’s not remotely comparable to the bad elites of previous centuries.

This loss of perspective tarnishes Deneen’s argument throughout the book — a problem most vividly on display in his treatment of the divide between “the many” and “the few.”

In Deneen’s thinking, it is axiomatic that the central divide in Western politics is between the villainous liberal elite (the “few”) and the culturally conservative mass public (“the many”). The liberal elites wish to impose their cultural vision on society and attack the customs and traditions of ordinary people; the many, who are instinctively culturally conservative, have risen under the banner of leaders like Trump to oppose them.

Except how do we know that liberals really are “the few?”

Deneen doesn’t cite election or polling data to support his theory of a natural conservative majority. Trump has never won the popular vote while on the ballot; his party performed historically poorly in two midterm elections since his rise to power. Polling on the cultural issues Deneen so cares about, like same-sex marriage, often finds majority support for liberal positions.

And even if you use the term “the many” as interchangeable with “non-college working class,” as Deneen seemingly does at times throughout the book, you need to seriously grapple with the significant partisan racial divide between white and non-white workers. Deneen does not, choosing instead to conspiratorially dismiss this gap as a product of elite manipulation rather than a reflection of deep and authentic political commitments among non-white voters.

When Machiavelli writes of the elite in Italian city-states, or Tocqueville about the French aristocracy, they are talking about conflict between an ocean of peasants and a single-digit percentage of the population with land and titles, not between two swaths of the mass public.

Deneen’s expansive definition of the “elite” requires him to treat grad students as if they were dukes. They are not — but there’s a reason Deneen seems to think they are.

The world’s tiniest regime change

Typically, when one hears a critique of “liberalism” as vehement as Deneen’s, you expect there to be some effort to establish an alternative set of political arrangements to the ones that characterize liberalism.

Deneen refuses to do that. Instead, he argues, things can be made better while keeping the political system mostly the same — so long as conservatives are in positions of power rather than liberals.

“What is needed, in short, is regime change — the peaceful but vigorous overthrow of a corrupt and corrupting liberal ruling class and the creation of a postliberal order in which existing political forms can remain in place, as long as a fundamentally different ethos informs those institutions and the personnel who populate key offices and positions,” he writes.

In that passage and elsewhere, Deneen frequently works to make his ideas sound radical. He calls for an “aristopopulism” in which “the few consciously take on the role of aristoi” and begin regime change via “the raw assertion of political power.”

But a closer look at Deneen’s “Machiavellian means” for transforming America shows the rhetoric to be a touch overheated. Most of his ideas are already under consideration (in one form or another) by elements of the current American elite. Here’s a representative selection of Deneen’s proposals:

- Move elements of the federal bureaucracy out of Washington, DC

- Create a national service program

- Improve domestic manufacturing capabilities through tariffs and subsidies

- Prosecute bosses who employ undocumented immigrants

- Shame media outlets that promote “transgression and libertinism”

- Provide subsidies and tax benefits to families, especially those with more children

- “Most importantly,” bring Christianity into public life through steps like public prayer and closure of businesses on Christian holidays

Some of the policies Deneen advocates, like putting wage earners on corporate boards, seem like good ideas. Others, like reimposing the draft, seem unwise. Some are silly (replacing primaries with caucuses) or even unconstitutional (a ban on pornography). But none are outside the realm of what’s talked about by mainstream liberals and conservatives — both of whom Deneen sees as philosophical liberals of slightly different stripes. In fact, versions of many of his policies already exist at the state and federal level.

There is no structural transformation proposed in the book, akin to the working class seizing the means of production, that marks a meaningful break with the existing order. If every single one of the above ideas were implemented across the country overnight, the same kinds of people would mostly be in charge of America’s core institutions. Even by his shrunken definition of what “regime change” means, this isn’t it.

There is one exception to this pattern: his proposals for higher education. In that realm, Deneen actually does call for a wholesale political attack.

The federal government, he argues, should work to ensure that university enrollment “be substantially reduced,” with more opportunities for vocational training and “a significant direction of public funds [away from] a higher education industry that has increasingly become a highly partisan and ideological program.”

Federal research funding should be contingent on “genuine socioeconomic variety” in the student body. State schools specifically should get more support, but conditioned on “expectations that faculty and administrators at public institutions respect the social and political commitment of the broader public.”

Here, broadly speaking, are our “Machiavellian” means: a comprehensive plan for using state power to replace the leftists and liberals in campus administration and faculty lounges with conservatives.

This book is not a comprehensive plan for remaking America. It is faculty politics by other means.

Elite-on-elite violence

In academia, Deneen is a religious conservative among secular liberals, and it’s clear that really bothers him.

In 2004, he was denied tenure at Princeton, a decision he blames in part on liberal bias. In 2012, he departed a position at Georgetown for Notre Dame on grounds that the former was too liberal and not Catholic enough.

“Georgetown increasingly and inevitably remakes itself in the image of its secular peers, ones that have no internal standard of what a university is for other than the aspiration of prestige for the sake of prestige, its ranking rather than its commitment to Truth,” he wrote in a letter to students. “I have felt isolated and often lonely at the institution where I have devoted so many of my hours and my passion.”

Throughout Regime Change, Deneen returns again and again to the university to illustrate the ills of liberal society. Whether it’s cancel culture at Middlebury College or the eclipse of theology courses by ethnic studies or the transformation of professors into “a version of ‘idiot-savants,’” much of Deneen’s brief against modernity centers on what happens in the university. He explicitly blames the political rise of “tyrannical liberalism” on universities.

“Universities … are today in the forefront of advancing new principles of despotism,” he argues. “These educational institutions help shape the worldviews and expectations of the managerial ruling class, who then deploy to a variety of settings where those lessons come to shape most of the main organizations that govern daily life.”

Throughout the text, his desire to turn Christian conservatism into the faculty lounge’s lingua franca, to make liberal professors suffer in the minority the way he has, is palpable. “Only the fear of not conforming to the regnant ethos will sufficiently move and shape elites — just as it does today to an elite that enforces a progressivist worldview,” he writes.

Here, Deneen is far from alone. Conservative and center-left elites who panic about “wokeness” and “cancel culture” focus their fire disproportionately on elite institutions: top 20 colleges, the New York Times, prominent artistic institutions, and major book publishers. People respond to what they see in their personal life. It’s one thing to hear about someone getting laid off at a factory in a small town, and another thing altogether for a friend — or you personally — to be denied tenure for believing the wrong things.

This has led to a consistent overstatement of the scope of the problem of “wokeness” and “identity politics.” Deneen’s book is, on the whole, a striking example of this trend — a denunciation of the cloistered nature of the American elite that, ironically, falls victim to the very problem it identifies.

I wanted to ask Deneen about how he would respond to this line of criticism, among others, so I reached out to him over email partway through reading the book. He not-so-politely refused.

“I’m quite certain you’re unlikely to deviate from any conclusions you’ve already settled upon, regardless of what I might try to convey in response to any questions,” he told me. This was a shame. There’s something important to his critique of liberalism I would’ve liked to tease out more — even some more personal room for common ground, given my own increasing appreciation for religion and the need for community as I’ve aged.

But after finishing the book, I’m not sure I should have expected anything different. If he really believed what he was arguing, he would indeed have limited interest in engaging with members of the liberal laptop class “elite” such as myself. If liberals truly are the enemy, the people he aims to overthrow, why opt for conversation rather than conflict?

Outside President Trump’s arraignment at a federal courthouse in Miami yesterday, a guy with a pig head on a pike got there early. So did a woman in a fluorescent yellow high-viz vest with a big Q on the back. But the violence some feared failed to materialize. And the final turnout in front of the courthouse was nowhere near the crowds of 50,000 rallying in support of their leader that local police officials said they were prepared to take on.

The threat that wasn’t was easy to mock. “Nice turnout Trump, you clown,” jeered Bill Mitchell, a MAGA Twitter guy turned DeSantis supporter. “There’s no shame in not having people protest your arrest and indictment,” Rachel Maddow said on her Tuesday night coverage of the paltry showing. “Except when you have begged people to.”

But there is another factor, as reporting ahead of Trump’s court appearance showed: Some of the groups who had been key to turning January 6 from a protest into a riot were busy closer to home. While it’s true that the low turnout would seem like a bad look for a strongman, it does not mean that Trump has lost the ability to call his flock to his aid. In truth, they are already mobilized—just elsewhere, and no less in service to all that Trump stands for.

Trump had issued an invitation, posting on June 9, “SEE YOU IN MIAMI ON TUESDAY!!!”—much, much closer to the date than his “will be wild” tweet for January 6—and was able to draw hundreds of people to the courthouse for a relatively routine protest. But far-right researchers and extremism experts had cautioned ahead of the hearing that the turnout and intensity expected in Miami may amount to little. As a recent publication from the human rights group Institute for Strategic Dialogue, or ISD, explained, there were plenty of indicators that Trump supporters would largely stay home: Absent a specific call to action and resources to support protesters, and without trusted figures and influencers amplifying the call to a broader audience, a mass demonstration is unlikely get off the ground.

“Potential protests associated with increasingly polarized political causes continue to be subjects of mass-media hype cycles, influencing and engendering hysteria around the event,” wrote ISD’s Jared Holt and Katherine Keneally. These hype cycles, they explain, are driven by reports that “lift hand-picked comments from the internet—such as talks of civil war or fantasies of executing politicians—and strip them of crucial context.”

What follows such flawed predictions is closer to what we saw in images coming out of Tuesday’s protests at the courthouse. Journalists on the scene reported they at times outnumbered the actual MAGA supporters. News cameras captured a riot of other outlets’ tripods, corralled by bike cops—far from anything resembling a replay of January 6.

Still, that led some commentators to assume Trump was flailing. “This flop is a clear sign of weakness for the authoritarian populist,” noted MSNBC columnist Zeeshan Aleem. But the front lines were never going to be in Miami—nor in lower Manhattan, where only around 50 to 60 pro-Trump protesters turned up in March for his indictment there, nor (as many anticipate an upcoming indictment on yet more criminal charges) in Atlanta. The front lines are much closer to home, in conflicts kicked off by Trump supporters in school board meetings, outside public libraries, and constantly—at all hours—on the phone in your pocket.

Far-right extremism mainstreamed during the Trump presidency. In the aftermath, it has moved “from the mainstream to the main street,” as Susan Corke, director of the Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center, wrote in a 2022 report released last week. “Extremist actors—often armed—brought hatred into our daily lives and public spaces, protesting LGBTQ inclusion, reproductive rights and classroom discussions of systemic racism.”

These days, you are more likely to find the Proud Boys menacing a Drag Story Hour or Pride event than responding to a call from Trump. Just days before Trump’s court appearance in Miami, Proud Boys descended on a school board meeting in Glendale, California, in an attempt to intimidate the board from voting to recognize Pride Month. It’s part of an escalation that extremism researchers have been monitoring: Groups like the Proud Boys, Patriot Front, and others have increased their participation in anti-LGBTQ actions threefold from 2021 to 2022, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project reported.

It seems right now that anywhere expressing support for queer and trans communities—from formerly routine local Pride rallies to the aisles of Target—has become the front line of extremist activity. This extends out to the information war on TikTok and Twitter, where an endless stream of content paints LGBTQ people—particularly trans people—as monsters. We may not see mass mobs of fascists so much on cable news—we may even imagine this all as waged by lone or isolated extremists—but their actions are no less disconnected from the mob power Trump flexed at the Capitol on January 6.

This is the path political violence has followed for decades in the United States, though in different forms. Veterans have been a reliable source of trained-up recruits for white power and militia groups, as historian Kathleen Belew documents in her book Bring the War Home. Belew argued against the idea of the lone wolf, emphasizing the far right’s turn toward a strategy of “leaderless resistance”: Like Timothy McVeigh, who bombed the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 and who was in turn inspired by the ATF raid and subsequent destruction of the Branch Davidian compound at Waco, Texas. Those who were mobilized and perhaps further radicalized by January 6 have also gone home, bringing the MAGA fight with them.

The divide in this slow civil war, as journalist Jeff Sharlet has called it, doesn’t run between North and South, but within our own communities. When someone like Louisiana Republican Congressman Clay Higgins takes to Twitter to summon his own militia (he has previously identified with that movement) in cringey military jargon, it can be tempting to mock him, Sharlet wrote for The Atlantic just ahead of the Miami protest. “Such are the means by which some imagine the center still holds.” But humor, he noted, is no “antidote to fascism, a term that more and more historians and political scientists say at last applies to a mass American movement, even as many news organizations still shy away from it.”

The circuslike scene following Trump around the country is easy to laugh at—and it makes sense that people want to, for the alternative is a far scarier proposition. The kind of violence seen at the Capitol one and a half years ago should not be presumed dead simply because it has reorganized itself, diffused itself, and taken up occupation in communities across the U.S. There is also some hope in that: Rather than steel ourselves for January 6, 2025, we could begin defending ourselves from the threat of fascism where we live, confronting it, unwinding it, before it explodes again.

Alfred McCoy, Ending Putin’s Forever War in Ukraine

[Note for TomDispatch Readers: As you check out today’s post, give a thought to getting your hands on the new paperback version of To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change, Alfred McCoy’s remarkable history of our imperial world from the Portuguese empire of the sixteenth century to late tomorrow night. Updated and with a new introduction, it’s quite a read! And let me remind you that, for a $125 donation to this site ($150 if you live outside the U.S.), you can get a signed, personalized copy of the paperback and, while you’re at it, ensure that future pieces like his today will continue to appear at TomDispatch. As ever, this site needs your help! So, consider visiting our donation page and doing whatever you can. Believe me, it will be appreciated! Tom]

Yes, a crucial Ukrainian dam is destroyed, the downriver communities flood, and the danger to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant only grows. It could prove Ukraine’s worst ecological disaster since the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown of 1986. And yes, it’s that war again, the latest European conflict in a horrific history that extends to hell and back. And what’s on the mind of the top figures in the Biden administration and the U.S. military right now? How to end it as quickly as possible before further disaster strikes? Not a chance!

After all, as I wrote so many years ago, the U.S. lives in a… well, in 2023, you would have to say the dregs of a “victory culture” and, in a Washington still filled with relics from the Cold War era (including our president), peace is not exactly at the top of anyone’s agenda. In fact, in a recent speech, Secretary of State Antony Blinken essentially chucked the very idea of peace, no less halting the war in Ukraine, however briefly, out the window. “Some countries,” he said, “will call for a ceasefire. And on the surface, that sounds sensible — attractive, even. After all, who doesn’t want warring parties to lay down their arms? Who doesn’t want the killing to stop? But a ceasefire that simply freezes current lines in place and enables Putin to consolidate control over the territory he’s seized… It would legitimize Russia’s land grab. It would reward the aggressor and punish the victim.”

And yes, amid the chaos and rising destruction, the Ukrainian “spring” counteroffensive (which only really started last week) is on its way, but whatever gains it may make, one thing is distinctly unlikely: that the Ukrainians will be capable of triumphing in a war with a Russia that, whatever its (many) problems, is simply the larger and more powerful of the two countries. The question then becomes: How — short of escalating to the nuclear level — could this disastrous war near the heart of Europe possibly end?

With that question in mind, let TomDispatch regular Alfred McCoy, author of the aptly titled history of the rise and fall of empires To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change, suggest how it might finally conclude. While he’s at it, let him also explain how that very ending might mark a new stage in the rise — and fall — of imperial powers on this beleaguered planet of ours. Tom

Peace for Ukraine Courtesy of China?

Another Step in Beijing’s Rise to Global Power

All wars do end, usually thanks to a negotiated peace agreement. Consider that a fundamental historical fact, even if it seems to have been forgotten in Brussels, Moscow, and above all, Washington, D.C.

In recent months, among Russian President Vladimir Putin’s followers, there has been much talk of a “forever war” in Ukraine dragging on for years, if not decades. “For us,” Putin told a group of factory workers recently, “this is not a geopolitical task, but a task of the survival of Russian statehood, creating conditions for the future development of the country and our children.”

Visiting Kyiv last February, President Joseph Biden assured Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky, “You remind us that freedom is priceless; it’s worth fighting for, for as long as it takes. And that’s how long we’re going to be with you, Mr. President: for as long as it takes.” A few weeks later, the European Council affirmed “its resolute condemnation of Russia’s actions and unwavering support for Ukraine and its people.”

With all the major players already committed to fighting a forever war, how could peace possibly come about? With the U.N. compromised by Russia’s seat on the Security Council and the G-7 powers united in condemning “Russia’s illegal, unjustifiable, and unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine,” the most likely dealmaker when it comes to ending this forever war may prove to be President Xi Jinping of China.

In the West, Xi’s self-styled role as a peacemaker in Ukraine has been widely mocked. In February, on the first anniversary of the Russian invasion, China’s call for negotiations as the “only viable solution to the Ukraine crisis” sparked a barbed reply from U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan who claimed the war “could end tomorrow if Russia stopped attacking Ukraine.”

When Xi visited Moscow in March, the statement Chinese officials released claiming that he hoped to “play a constructive role in promoting talks” prompted considerable Western criticism. “I don’t think China can serve as a fulcrum on which any Ukraine peace process could move,” insisted Ryan Hass, a former American diplomat assigned to China. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, pointed out that “China has taken sides” in the conflict by backing Russia and so could hardly become a peacemaker. Even when Xi made a personal call to Zelensky promising to dispatch an envoy to promote negotiations “with all parties,” critics dismissed that overture as so much damage control for China’s increasingly troubled trade relations with Europe.

The Symbolism of Peace Conferences

Still, think about it for a moment. Who else could bring the key parties to the table and potentially make them honor their signatures on a peace treaty? Putin has, of course, already violated U.N. accords by invading a sovereign state, while rupturing his economic entente with Europe and trashing past agreements with Washington to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty. And yet the Russian president relies on China’s support, economically and otherwise, which makes Xi the only leader who might be able to bring him to the bargaining table and ensure that he honors any agreement he signs. That sobering reality should raise serious questions about how any future Beijing-inspired peace conference might happen and what it would mean for the current world order.

For more than 200 years, peace conferences have not only resolved conflicts but regularly signaled the arrival at stage center of a new world power. In 1815, amid the whirling waltzes in Vienna’s palaces that accompanied negotiations ending the Napoleonic wars, Britain emerged for its century-long reign as the globe’s greatest power. Similarly, the 1885 Berlin Conference that carved up the continent of Africa for colonial rule heralded Germany’s rise as Britain’s first serious rival. The somber deliberations in Versailles’s grand Hall of Mirrors that officially ended World War I in 1919 marked America’s debut on the world stage. Similarly, the 1945 peace conference at San Francisco that established the U.N. (just as World War II was about to end) affirmed the ascent of U.S. global hegemony.

Imagine the impact if, sooner or later, envoys from Kyiv and Moscow convene in Beijing beneath the gaze of President Xi and find the elusive meeting point between Russia’s aspirations and Ukraine’s survival. One thing would be guaranteed: after years of disruptions in the global energy, fertilizer, and grain markets, marked by punishing inflation and spreading hunger, all eyes from five continents would indeed turn toward Beijing.

After all, with the war disrupting grain and fertilizer shipments via the Black Sea, world hunger doubled to an estimated 345 million people in 2023, while basic food insecurity now afflicts 828 million inhabitants of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Should such negotiations ever prove fruitful, a televised signing ceremony, hosted by President Xi and watched by countless millions globally, would crown China’s rapid 20-year ascent to world power.

Forget Ukraine for a moment and concentrate on China’s economic rise under communist rule, which has been little short of extraordinary. At the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, China was an economic lightweight. Its massive population, 20% of the world’s total, was producing just 4% of global economic output. So weak was China that its leader Mao Zedong had to wait two weeks amid a Moscow winter for an audience with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin just to plead for the industrial technology that would help rebuild an economy devastated by 12 years of war and revolution. In the decade following its admission to the World Trade Organization in 2002, however, China quickly became the workshop of the world, accumulating an unprecedented $4 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves.

Instead of simply swimming in a hoard of cash like Scrooge McDuck in his Money Bin, in 2013 President Xi announced a trillion-dollar development scheme called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Its aim was to build a massive infrastructure across the Eurasian landmass and Africa, thereby improving the lives of humanity’s forgotten millions, while making Beijing the focal point of Eurasia’s economic development. Today, China is not only an industrial powerhouse that produces 18% of the global gross domestic product, or GDP (compared to 12% for the U.S.), but also the world’s chief creditor. It provides capital for infrastructure and industrial projects to 148 nations, while offering some hope to the quarter of humanity still subsisting on less than four dollars a day.

Testifying to that economic prowess, for the past six months, world leaders have ignored Washington’s pleas to form a united front against China. Instead, remarkable numbers of them, including Germany’s Olaf Scholz, Spain’s Pedro Sánchez, and Brazil’s Lula da Silva, have been turning up in Beijing to pay court to President Xi. In April, even French President and U.S. ally Emmanuel Macron visited the Chinese capital where he proclaimed a “global strategic partnership with China” and urged other countries to become less reliant on the “extraterritoriality of the U.S. dollar.”

Then, in a diplomatic coup that stunned Washington, China took a key step toward healing the dangerous sectarian rivalry between Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia by hosting a meeting of their foreign ministers in Beijing. As the Saudis’ chief oil customer and Iran’s largest creditor, Beijing had the commercial clout to bring them to the bargaining table. China’s top diplomat Wang Yi then hailed the restored diplomatic relations as part of his country’s “constructive role in facilitating the proper settlement of hot-spot issues around the world.”

Geopolitics as a Source of Change

Underlying the sudden display of Chinese diplomatic clout is a recent shift in that essential realm called “geopolitics” that’s driving a fundamental realignment in global power. Around 1900, at the high tide of the British Empire, an English geographer, Sir Halford Mackinder, started the modern study of geopolitics by publishing a highly influential article arguing that the construction of the 5,000-mile-long Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok was the beginning of a merger of Europe and Asia. That unified land mass, he said, would soon become the epicenter of global power.

In 1997, in his book The Grand Chess Board, former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brezinski updated MacKinder, arguing that “geopolitics has moved from the regional to the global dimension, with preponderance over the entire Eurasian continent serving as the central basis for global primacy.” In words particularly apt for our present world, he added: “America’s global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained.”

More than a quarter-century later, imagine geopolitics as a deep substrate shaping far more superficial political events, even if it’s only noticeable in certain moments, much the way the incessant grinding of the planet’s tectonic plates only becomes visible when volcanic eruptions break through the earth’s surface. For centuries, if not millennia, Europe was separated from Asia by endless deserts and sprawling grasslands. The empty center of that vast land mass was crossed only by an occasional string of camels travelling the ancient Silk Road.

Now, thanks to its trillion-dollar investment in infrastructure — rails, roads, pipelines, and ports — China is fundamentally changing that geopolitical substrate through a more than metaphoric merger of continents. If President Xi’s grand design succeeds, Beijing will forge a unified market stretching 6,000 miles from the North Sea to the South China Sea, eventually encompassing 70% of all humanity, and effectively fusing Europe and Asia into a single economic continent: Eurasia.

Despite the Biden administration’s fervid attempts to create an anti-Chinese coalition, recent diplomatic eruptions are shaping a new world order that isn’t at all what Washington has in mind. With the economic creation of a true Eurasian sphere seemingly underway, from that Iran-Saudi entente to Macron’s visit to Beijing, we may be seeing the first signs of the changing face of international politics. The question is: Could a Chinese-engineered peace in Ukraine be next in line?

Pressures on China for Peace

Such growing geopolitical power is giving China both the motivation and potentially even the means to negotiate an end to the fighting in Ukraine. First, the means: as Russia’s chief customer for its commodity exports, and Ukraine’s largest trading partner before the war, China can use commercial pressure to bring both parties to the bargaining table — much as it did for Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Next, the motivation: while Moscow and Kyiv might each exude confidence in ultimate victory in their forever war, Beijing has reason to grow impatient with the economic disruptions radiating out across the Black Sea to roil a delicately balanced global economy. According to the World Bank, almost half of humanity (47%) is now surviving on seven dollars a day, and most of them live in Africa, Asia, and Latin America where China has made massive, long-term developmental loans to 148 countries under its Belt and Road Initiative.

With 70% of its lands and their rich black soils devoted to agriculture, Ukraine has, for decades, produced bumper crops of wheat, barley, soybeans, and sunflower oil that made it “the breadbasket of the world,” providing the globe’s hungry millions with reliable shipments of affordable commodities. Right after the Russian invasion, however, world prices for grains and vegetable oils shot up by 60%. Despite stabilization efforts, including the U.N.’s Black Sea Grain Initiative to allow exports through the war zone, prices for such essentials remain all too high. And they threaten to go higher still with further disruption of global supply chains or more war damage like the recent rupture of a crucial Ukrainian irrigation dam that’s turning more than a million acres of prime farmland into “desert.”

As costs for imports of fertilizer, grain, and other foodstuffs have soared since the Russian invasion, the Council on Foreign Relations reports that “a climbing number of low-income BRI countries have struggled to repay loans associated with the initiative, spurring a wave of debt crises.” In the Horn of Africa, for example, the sixth year of a crippling drought has pushed an estimated 23 million people into a “hunger crisis,” forcing the governments of Ethiopia and Kenya to balance costly food imports with the repayment of Chinese loans for the creation of critical infrastructure like factories, railroads, and renewable energy. With such loans surpassing 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in nations like Ghana, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Zambia, while China itself holds outstanding credits equivalent to 25% of its GDP, Beijing is far more invested in global economic peace and stability than any other major power.

Beyond Western Fantasies of Victory

At present, Beijing might seem alone among major nations in its concern about the strain the Ukraine war is placing on a world economy poised between starvation and survival. But within the coming six months, Western opinion will likely start to shift as its inflated expectations for Ukrainian victory in its long-awaited “spring counteroffensive” meet the reality of Russia’s return to trench warfare.

After the stunning success of Ukraine’s offensives late last year near Kharkiv and Kherson, the West dropped its reticence about provoking Putin and began shipping billions of dollars of sophisticated equipment — first, HIMARS and Hawk missiles, then Leopard and Abrams battle tanks, and, by the end of this year, advanced F-16 jet fighters. By the war’s first anniversary last February, the West had already provided Kyiv with $115 billion in aid and expectations of success rose with each new arms shipment. Adding to that anticipation, Moscow’s own “winter offensive” with its desperate suicide attacks on the city of Bakhmut suggested, as Foreign Affairs put it, that “the Russian military demonstrated… it was no longer capable of large-scale combat operations.”

But defense is another matter. While Moscow was wasting some 20,000 lives on suicide assaults on Bakhmut, its specialized tractors were cutting a formidable network of trenches and tank traps along a 600-mile front designed to stall any Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Ukraine’s troops will probably achieve some breakthroughs when that offensive finally begins, but are unlikely to push Russia back from all its post-invasion gains. Remember that Russia’s army of 1.3 million is three times larger than Ukraine’s which has also suffered many casualties. In March, the commander of Ukraine’s 46th Air Assault brigade told the Washington Post that a year of combat had left 100 dead and 400 wounded in his 500-man unit and that they were being replaced by raw recruits, some of whom fled at the very sound of rifle fire. To counter the few dozen “symbolic” Leopard tanks the West is sending, Russia has thousands of older-model tanks in reserve. Despite U.S. and European sanctions, Russia’s economy has actually continued to grow, while Ukraine’s, which was only about a tenth the size of Russia’s, has shrunk by 30%. Facts like these mean just one thing is likely: stalemate.

Beijing as Peacemaker

By next December, if Ukraine’s counteroffensive has indeed stalled, its people face another cold, dark winter of drone attacks, while Russia’s rising casualties and lack of results might by then begin to challenge Putin’s hold on power. In other words, both combatants might feel far more compelled to sit down in Beijing for peace talks. With the threat of future disruptions damaging its delicate global position, Beijing will likely deploy its full economic power to press the parties for a settlement. By trading territory, while agreeing with China on reconstruction aid, and some further strictures on Ukraine’s future NATO membership, both sides might feel they had won enough concessions to sign an agreement.

Not only would China then gain enormous prestige for brokering such a peace deal, but it might win a preferential position in the reconstruction bonanza that would follow by offering aid to rebuild both a ravaged Ukraine and a damaged Russia. In a recent report, the World Bank estimates that it could take $411 billion over a decade to rebuild a devastated Ukraine through infrastructure contracts of the very kind Chinese construction companies are so ready to undertake. To sweeten such deals, Ukraine could also allow China to build massive factories to supply Europe’s soaring demand for renewable energy and electric vehicles. Apart from the profits involved, such Chinese-Ukrainian joint ventures would ramp up production at a time when that country is likely to gain duty-free access to the European market.

In the post-war moment, with the possibility that Ukraine will be an increasingly strong economic ally at the edge of Europe, Russia still a reliable supplier of cut-rate commodities, and the European market ever more open to its state corporations, China is likely to emerge from that disastrous conflict — to use Brzezinski’s well-chosen words — with its “preponderance over the entire Eurasian continent” consolidated and its “basis for global primacy” significantly strengthened.

Many S&P 500 food and consumer-goods companies are still raising prices, making it harder for the Federal Reserve to tame high inflation.

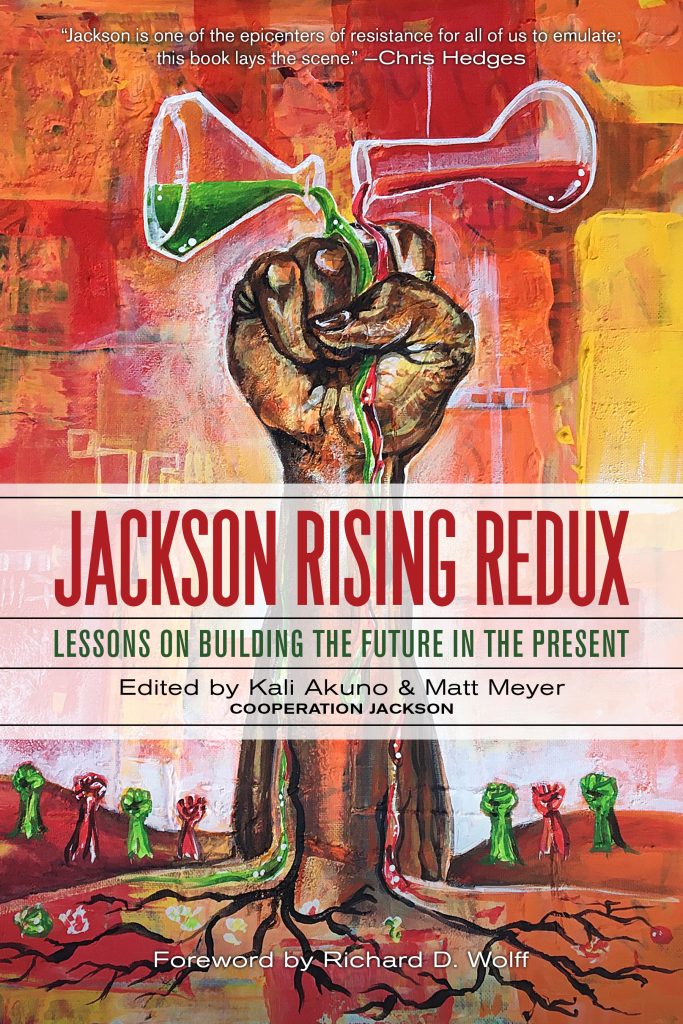

Collection of pieces looking at the campaign for a Black-led new municipalism in Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson Rising Redux: Lessons on building the future in Mississippi, ed Kali Akuno and Matt Meyer (PM Press)

Cooperation Jackson, a radical campaign to set up a Black-led, solidarity-based new municipalism, was born out of desperate crisis and centuries of oppression in the Mississippi city. But since a previous book documenting these endeavours – Jackson Rising (2018), the situation has grown more urgent: starved of funds by the state government, the city’s water supply has collapsed.

The underlying strains in the world economy have also increased, worsened by the pandemic and sparking a wave of reactionary populism around the world. In his foreword to this book, Richard D Wolf presents this as the beginning of the end for capitalism. If that’s the case, it’s important to attend to what comes next: the co-op model, and efforts towards a new municipalism in cities like Cleveland, Ohio and Preston, Lancashire have long been touted as an option.

Jackson Rising Redux is latest in a series of books published in the last year or so which make the case for this co-operative new economy. But with the poorest state in the USA as its base, and with the racial injustices that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement continuing unabated, it states that case with a singular urgency.

The book gathers academics and activists from around the world to discuss Cooperation Jackson in a range of contexts – local, international, historical, political, etc.

It begins with a history of the project by its co-founder Kali Akuno, who sets out the movement’s four goals: to place the ownership and control of the primary means of production in the hands of the Black working class in Jackson; to build and advance the development of the ecologically regenerative forces of production in the city; to democratically transform the political economy in the city and the wider south-eastern region; and to advance the Jackson-Kush Plan.

Related: Solidarity economy: Case studies from Rojava and Jackson, Mississippi

This was a radical movement formulated in the 2000s, with the goal of attaining self-determination for people of African descent and the radical, democratic transformation of the state of Mississippi.

Sacajawea ‘Saki’ Hall

Sacajawea ‘Saki’ HallIt’s a wide-ranging project, taking in the push for net zero, food sovereignty, green worker co-ops, mutual aid and sustainable communities. A tall order. Founder member, activist Sacajawea ‘Saki’ Hall, says the work is “filled with complexities, successes, failures, and everything in between”, as the fledgling movement struggled to mobilise support in the city’s population and clashed with the city government – led by Baba Chokwe Lumumba, son of the founder of the Jackson-Kush plan.

But she also points to achievements, such as an autonomous People’s Assembly which led to housing justice work, rent relief, an eviction hotline and rental assistance fairs. “We see in our everyday work that everyday working-class Black people in Jackson are ready to engage with and be introduced to radical ideas,“ she adds.

Hall also contributes a moving personal piece – setting out her ‘Beautiful Struggle’ in blend of verse and memories; this varied collection also includes a history of US Black co-operativism by Jessica Gordon Nembhardt, a look at a radical movement by marginalised people in Atlanta, Georgia by Yolanda M.S. Tomlinson, and a short discussion of the Preston model, Brexit and the British left by Daniel Brown.

This is a fascinating book, an inspiring set of perspectives on a community fighting to organise itself after being pushed beyond the limit.

There are already accomplishments – the Lawn Care Cooperative is becoming self-sustaining, and the Freedom Farms Cooperative has weathered a bad winter to supply food to co-ops, markets and restaurants in the city; the Community Production Cooperative is carrying out training; and the Fannie Lou Hamer Community Land Trust has more than 40 parcels of land. Hopefully the next book on Jackson Rising will present further stories of progress.

Available from PM Press: UK website £23.99; US website $24.95

The post Cooperation Jackson: Updates on a citizen-led struggle to transform a city of injustice appeared first on PM Press.

Editor’s note: The below article first appeared in David Corn’s newsletter, Our Land. The newsletter comes out twice a week (most of the time) and provides behind-the-scenes stories and articles about politics, media, and culture. Subscribing costs just $5 a month—but you can sign up for a free 30-day trial of Our Land here. Please check it out.

On Thursday, Pat Robertson, the television preacher and founder of the Christian Broadcasting Network, died at the age of 93. The obituaries duly noted that he transformed Christian fundamentalism into a potent political force with the Christian Coalition that he founded in 1990 and that became an influential component of the Republican Party. They also included an array of outrageous and absurd remarks he had made over the years. He blamed natural disasters on feminists and LGBTQ people. He called Black Lives Matter activists anti-Christian. He said a devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti occurred because Haitians had made a “pact with the devil” to win their freedom from France. He prayed for the deaths of liberal Supreme Court justices. He insisted the 9/11 attacks happened because liberals, feminists, and gay rights advocates had angered God. He claimed Kenyans could get AIDS via towels. He insisted Christians were more patriotic than non-Christians. He purported to have prayed away a hurricane from striking Virginia Beach. (The storm hit elsewhere.)

Yet left out of the accounts of Robertson’s life was a basic fact: He was an antisemitic conspiracy theory nutter.

In 1991, Robertson published a book called The New World Order. As I noted in my recent book, American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy, it was a pile of paranoia that amassed assorted conspiracy theories of the ages. He melded together unfounded tales of secret societies, such as the Illuminati and the Masons, and claimed they and their secret partners—communists, elites, and, yes, occultists—had for centuries plotted to imprison the entire world in a godless, collectivist dictatorship. The list of colluders was mind-blowingly long: the Federal Reserve, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, the Ford Foundation, the J.P. Morgan bank, the United Nations, the Rockefellers, Henry Kissinger, and many others. (Okay, maybe he was correct about Kissinger.) Also in on it were “European bankers,” including the Rothschild family, long a target of antisemitic conspiracy theories that Robertson echoed.

In the book, he called the Rothschilds possibly “the missing link between the occult and the world of high finance.” He asserted that Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Jimmy Carter, and George H.W. Bush had “unwittingly” carried out “the mission” and mouthed “the phrases of a tightly knit cabal whose goal is nothing less than a new order for the human race under the domination of Lucifer and his followers.”

Robertson was saying that the first President Bush was a Satanic dupe and fronting for a nefarious global elite that was in league with Beelzebub. What was his evidence for this? Bush had repeatedly in speeches referred to the “new world order.” Now that’s some high-powered logic.

The Christian leader—who was fervently courted by Republican politicians who yearned for campaign cash, volunteers, and votes from the Christian Coalition—offered an apocalyptic view of the future. Looking at the US military action Bush had launched earlier that year that had repelled Iraqi forces from Kuwait and interpreting it according to the Book of Revelation, Robertson maintained that the Persian Gulf War was a sign that “demonic spirits” would soon unleash a “world horror” that would kill 2 billion people. (You might recall that did not happen.)

His The New World Order transmitted classic antisemitic garbage and the swill of conspiracism, within an end-is-near biblical narrative. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies and became a bestseller. The Wall Street Journal described the work as a “compendium of the lunatic fringe’s greatest hits.” Robertson was pushing a narrative that had been adopted by the right over the previous decades: Democrats and liberals (and even some numbskull Republicans) were not just wrong on issues; they were a Devil-driven clandestine operation seeking to annihilate the United States and Christianity. They were pure evil.

On his television show, Robertson repeatedly served up this dark message for the faithful. During one broadcast, he exclaimed, “Just like what Nazi Germany did to the Jews, so liberal America is doing to evangelical Christians. It’s no different…It is the Democratic Congress, the liberal-biased media, and the homosexuals who want to destroy all Christians.” This was a foul and hysterical comparison: Democrats were the equivalent of Hitler and committing genocide against Christians. Robertson begged viewers to donate $20 a month: “Send me money today or these liberals will be putting Christians like you and me in concentration camps.”

Yet the Republican Party welcomed Robertson, who had mounted a failed campaign for the GOP presidential nomination in 1988, into its tent. Top Republicans trekked to Christian Coalition conferences to kiss his ring. In search of political support and money, they validated an antisemitic and paranoid zealot and signaled to his followers and the world that he was worth heeding and that his dangerous and tribalist propaganda ought to be believed.

In 1992, Bush addressed the Christian Coalition’s second annual conference. He hailed Robertson for “all the work you’re doing to restore the spiritual foundation of this nation.” He then attended a private reception with major contributors to the coalition in the rose garden of Robertson’s estate. Black swans swam in a pond, a harpist played, and Bush warmly greeted members of the televangelist’s inner circle. Presumably, Bush’s alliance with Satan was not mentioned.

Robertson got away with being a crazy antisemite because Republicans needed him and his following. His Christian Coalition aided a great many GOP politicians in getting elected. This included George W. Bush, the son of that Satanic tool. In 2000, the younger Bush called on the Christian Coalition to help him win the crucial South Carolina primary and beat back the threat of Sen. John McCain. In one of the nastiest political battles in modern history, Robertson’s troops rallied, and Bush’s presidential prospects were saved.

Robertson had inherited the religious right from Jerry Falwell, who had created the Moral Majority in the late 1970s, and he further—and perhaps more effectively—injected Christian fundamentalism into electoral politics. His grand view was demented and detrimental to a diverse and democratic society. It paved the way to the divisive politics of Newt Gingrich, Sarah Palin, the tea party, and, yes, Donald Trump.

And he was bonkers.

Yet because this antisemite was embraced and enabled by the GOP, he had a tremendous impact on the political life of the United States. Reflecting on Robertson’s death, historian Rick Perlstein told the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent, “The idea that God’s law trumps man’s law absolutely saturates [Robertson’s] world. Along with Falwell, he’s most responsible for turning Christianity into Christian nationalism and Christian nationalism into insurrectionism.”

Given all the damage Robertson did and all the hatred he spread, it’s hard to wish him a peaceful rest in eternity.