Holidays in my childhood were spent at my grandparents’ farm in Plain Grove, Pennsylvania, 35 miles from East Palestine, Ohio. My grandfather’s grandfather fought at Gettysburg and homesteaded the 160-acre farm after the Civil War. My grandmother sold it in the 1960s for $13,000, lacking a male heir to do the work; but my relatives still live in the area. I have therefore taken a keen interest in…

Archive for category: #Capitalism #EconomicCrisis #Finance

REUTERS/Steve Marcus

- Paul Singer sounded recession alarms and warned of a lengthy period of low returns.

- The hedge fund manager said the US economy is facing an “extraordinarily dangerous and confusing period,” per the WSJ.

- Singer previously called the subprime mortgage crisis and warned of the post-Covid inflation spike.

Billionaire hedge fund proprietor Paul Singer warned investors of a prolonged market cycle of low returns in financial assets as recession risks continue to mount.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page, the founder of Elliott Management and one of the world’s most notable money managers said the US economy is facing an “extraordinarily dangerous and confusing period.”

Financial markets are facing a slew of obstacles on top of an already difficult macro environment as the Federal Reserve and other central banks continue to hike interest rates to battle stubbornly high inflation.

“Valuations are still very high. There’s a significant chance of recession,” Singer said. “We see the possibility of a lengthy period of low returns in financial assets, low returns in real estate, corporate profits, unemployment rates higher than exist now and lots of inflation in the next round.”

And if the next recession hits, central bankers will ease monetary policy again, thinking that inflation has been conquered, he added. But inflation will come back, possibly even more than before, meaning rates will have to go higher for longer, he said.

Singer was one of the first to call the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, and warned of high inflation at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In an April 2020 letter to investors, Singer said: “We think it is very unlikely that central bankers will move to normalize monetary policy after the current emergency is over… The world has moved demonstrably closer to a tipping point after which money printing, prices and the growth of debt are in an upward spiral that the monetary authorities realize cannot be broken except at the cost of a deep recession and credit collapse.”

“After a decade of action, we are making a difference in the fight against climate change,” proclaims DivestInvest, the global divestment network. Dozens of leading climate organizations from 350.org to the World Council of Churches have enlisted as core partners or endorsers of DivestInvest.

According to DivestInvest’s website, 1,585 institutions have publicly committed to “at least some form” of fossil fuel divestment, representing an enormous $39.2 trillion of assets under management.

“That’s as if the two biggest economies in the world, the United States and China, combined, chose to divest from fossil fuels,” the site goes on.

DivestInvest’s 2021 glossy prospectus intimates that, thanks to divestment, the fossil fuel industry has begun to collapse. At the very least, oil and gas moguls should be trembling with fear that divestment activists will soon force them to close their spigots and relinquish their financial and political power.

If only this were true.

The balance sheets of the fossil fuel companies say otherwise. Instead of the industry tailspin portrayed in DivestInvest’s report, the fossil fuel giants are awash in record profits. In 2021, The Hill reports, “the four largest oil and gas companies made over $75 billion in profits, returned billions to their shareholders through record dividends and share buybacks, and handed out millions in compensation to their chief executive officers.”

Number two U.S. oil company Chevron’s stock hit an all-time high of $186.13 on January 26, 2023. After 10 years of divestment activism targeting the fossil fuel industry, loyal Chevron investors saw the dollar value of their nest eggs double. In April 2022 Chevron posted its highest quarterly profit in 10 years.

Worldwide fossil fuel production keeps rising. The U.S. government’s Energy Information Administration expects U.S. fossil fuel production to reach new highs in 2023.

Chart of Chevron stock price over the last 30 years. Source: macrotrends.net

Clearly, whatever the value of the divestment movement, it is not hitting the fossil fuel industry where it hurts.

How can this be?

Divestment and Its Discontents

The divestment movement began in earnest when Bill McKibben penned “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” for the August 2012 issue of Rolling Stone magazine. McKibben’s article did not actually make the case that divestment would lead to financial pain for the fossil fuel industry, but rather that it would bloody the industry’s reputation and identify it as “Public Enemy Number One.”

McKibben’s eloquent prose kicked off a campaign to pressure institutional investors to dump stock in fossil fuel companies. A group founded by McKibben and some university friends — 350.org — launched its Go Fossil Free: Divest from Fossil Fuels! campaign with the stated goal to “revoke the social license of the fossil fuel industry.”

McKibben went on a barnstorming tour across the country urging those concerned about climate to “Do the Math,” explaining the rationale behind divestment in strategic terms:

“The one thing we know the fossil fuel industry cares about is money. Universities, pension funds, and churches invest a lot of it. If we start with these local institutions and hit the industry where it hurts — their bottom line — we can get their attention and force them to change.”

The campaign spread rapidly from campus to campus. Many students got their first taste of collective action around climate. They learned basic skills of movement-building: organizing rallies, circulating petitions, knocking on doors, making speeches, devising slogans, pitching one-on-one in conversation, and creating posters, leaflets, and signs. Divestment provided clearcut targets and clearcut demands while leaving room for a variety of creative tactics.

Despite the obvious upsides, not everyone in the climate movement embraced McKibben’s call to place divestment at the center of climate action. Responding to McKibben, Christian Parenti, author of Tropic of Chaos and currently a professor of economics at the City University of New York, criticized 350.org’s focus on divestment in a 2012 op-ed that appeared here at Common Dreams:

“[T]he spectacle of targeting the enemy — giving them a name and an address — is great but it needs to be linked to other forms of leverage. Namely, we need to also focus on state power and what we can do with it. The movement should be demanding that government at every level move to contain and control Big Carbon and to directly support alternative energy. Regulation is the only thing that will actually check the industries — oil, gas, coal — that are destroying the planet.

“I am all for dumping carbon stocks, if for no other reason than a sense of decency and honor. But how is dumping oil stock supposed to hurt the enemy? The boards of oil companies will be embarrassed? The spectacle of the discussion around divestment might provoke actions on other fronts — like legislation? I am not at all clear on how this is supposed to work. And I am not sure McKibben or 350 are either.”

Parenti got slammed by some for questioning a tactic that would enable us to “take back our money and our souls.” Parenti provided a nuanced defense of his position in an interview that appeared in The Nation. Over time, a few other skeptics appeared.

After the heirs of oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller announced in 2014 that their charity would be divesting from fossil fuels, Journalist Matthew Iglesias wrote a short piece for Vox entitled “Does Fossil Fuel Divestment Work?” Iglesias explained that divestment neither deprives fossil fuel companies of capital nor drives down their stock prices, though it does inflict reputational damage on the fossil fuel industry.

Writing for The New Yorker in 2015, the philosopher William MacAskill addressed the question “Does Divestment Work?” and concluded, like Iglesias, that divestment campaigns might accomplish something, but not necessarily the kind of financial damage to the fossil fuel industry that activists unversed in industry economics often imagine:

“Divestment campaigns have the potential to do good, but only with caveats. To avoid the risk of misleading people, those running campaigns should be clear that the aim of divestment is to signal disapproval of certain industries, not to directly affect share price [emphasis added]. They should be clear that they aim to stigmatize the organizations (like fossil-fuel companies) that are being invested in, not those that do the investing (like universities, pension funds, or foundations). They should aim to maximize their media exposure. And, where possible, they should bundle the campaigns with actions that have larger direct effects, such as fossil-fuel energy boycotts, or with calls for specific policy changes.”

In April of 2018, the distinguished economist Robert Pollin and his coauthor Tyler Hansen of the Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst, published “How Well Does Fossil Fuel Divestment Combat Climate Change?” Their report was the first major scholarly study to evaluate the effectiveness of the divestment movement. Their conclusion:

“Divestment campaigns, considered on their own, have not been especially effective as a means of significantly reducing CO2 emissions, and they are not likely to become more effective over time.”

Ben Norton of the Real News Network presented Pollin’s conclusions and offered divestment advocates in the environmental movement an opportunity to respond. The divestment supporters more or less conceded that the value of their campaigns lay in removing validation, withdrawing social approval, and stigmatizing the fossil fuel industry — not in inflicting economic damage on fossil capital.

Let’s Stop Pretending

After 10 years of divestment activities having consumed large amounts of activist energy and funding, it is fair to ask whether these moral appeals have run their course. Aren’t we already fairly well sorted out into people who admire well-run, energy-efficient public transportation, electric cars, and bikes . . . and those who are more comfortable riding around in F-250 trucks and giant SUVs? Who is left to proselytize?

A nonprofit-industrial complex thrives on this campaign, but it’s time to go back and review what Parenti presciently explained years ago in his response to McKibben. By focusing on pressure campaigns against private actors with no direct effect on the fossil fuel industry, well-intentioned people inadvertently delay the necessary struggle to win and engage state power to phase out the extraction and production of fossil fuels.

Indeed, doing so buys into the neoliberal logic that government can do nothing when, in fact, only government can shut down the fossil fuel industry. There is no evidence that the divestment strategy of persuading a quorum of capitalist financiers to abandon the most powerful and profitable industry on earth will achieve success before the planet blazes past 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) of global warming.

As fossil fuel industry consultant Cyril Widdershoven observed last October, “The impact of these gestures is limited in an environment where demand is only increasing and returns are very impressive for those who do invest.” Thus divestment may even have the paradoxical effect of increasing future returns per share as the fossil fuel industry reaps record profits and uses them to buy back shares from divesting institutions.

So, What to Do?

There is plenty to do that might actually have the desired effect of ending the fossil industries. It should be clear by now to everyone that the only effective way to cut fossil fuel production at the necessary pace and scale is by direct regulation of the fossil fuel industry.

NGOs, activists, and especially policymakers need to stop pretending that our climate movement can succeed by pressuring capitalists to be more responsible through market mechanisms like changing who owns the shares of companies that pollute. Remember that every divested share of a fossil fuel company winds up in a different investor’s hands. How does that stop the industry that is hell-bent on baking the planet?

This is not to say that all strategies focused on blocking investment are a misallocation of movement energies. We should fight tooth and nail against every specific attempt to finance the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Where we can block the funding of particular projects by making them appear risky to investors or by campaigning against identified backers, our carefully targeted efforts to stop the money pipeline can be effective. When activists discovered that the Bank of Montreal was actively involved in attempting to raise $250 million to fund construction of a coal export terminal in Oakland, California, they launched a reputational campaign against the Bank of Montreal, which then vanished from the scene, leaving the coal project floundering.

Let’s no longer waste our limited energy, resources, and time on divestment campaigns that have no identifiable impact on specific fossil fuel projects. A winning climate movement must offer more than symbolic victories. Let’s focus on shared campaigns that build close working relationships and solidarity among the environmental, social, and worker justice movements.

Wen Stephenson

The post The Media’s Recent Turn to “Climate Optimism” Is a Cruel Fantasy appeared first on The Nation.

Banking turmoil has driven up spreads on sovereign bond yields over US Treasuries to levels that impair ability to raise funds

The US dollar still dominates debt markets, but some niche-sounding data suggests things could be set to shift

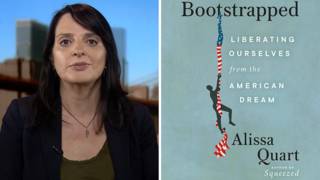

We speak with journalist Alissa Quart, executive director of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, about her new book, Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream, which examines myths about individualism and self-reliance that underpin the U.S. economy and the inequality it fosters. She says a focus on succeeding through hard work obscures the degree to which many rich and powerful people have benefited from social support, resulting in a cycle of “shame and blame” for those who fall short.

Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

- Sovereign defaults are at a record high, with 14 default events since 2020, Fitch said.

- That’s compared to 19 such events between 2000 and 2019, according to the ratings agency.

- Default events are also taking 107 days on average to resolve, up from 35 days in 2000, Fitch added.

Sovereign defaults have jumped exponentially in the last three years, according to a Fitch Ratings report published Wednesday.

Since 2020, 14 such events occurred across nine countries, compared to the prior two-decade span between 2000 and 2019 that saw 19 defaults across 13 different countries.

The surge in defaults comes as sovereign borrowing ramped up, with the median general government debt-to-GDP ratio climbing to 48% pre-Covid from 31% in 2008, helped by easier access to the eurobond market and financing from China.

“Against this backdrop, frontier markets with limited buffers were poorly placed to cope with the severe shocks from the pandemic and the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on food and energy prices, global inflation and the subsequent abrupt tightening in monetary policy,” Fitch said.

Currently, Belarus, Lebanon, Ghana, Sri Lanka and Zambia are in default. Other countries that underwent such events since 2020 include Argentina, Ecuador and Suriname, as well as Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Russia faced its own default last year, after Western sanctions limited its ability to pay back investors.

Default events are also taking longer to resolve, particularly due to a lack of coordination between Chinese stakeholders, in addition to China’s demand for multilateral debt within restructuring efforts.

While it took around 35 days to resolve a delinquency event in 2000, the average duration now takes around 107 days since 2020. Slower restructurings lead to higher financing costs, Fitch added.

Kilito Chan/Getty Images

- Generative AI could lead to “significant disruption” in the labor market, says Goldman Sachs.

- Researchers at the company estimated that the new tech could impact 300 million full-time jobs.

- AI systems could also boost global labor productivity and create new jobs, according to the report.

Generative artificial intelligence systems could lead to “significant disruption” in the labor market and affect around 300 million full-time jobs globally, according to new research from Goldman Sachs.

Generative AI, a type of artificial intelligence that is capable of generating text or other content in response to user prompts, has exploded in popularity in recent months following the launch to the public of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. The buzzy chatbot quickly went viral with users and appeared to prompt several other tech companies to launch their own AI systems.

Based on an analysis of data on occupational tasks in both the US and Europe, Goldman researchers extrapolated their findings and estimated that generative AI could expose 300 million full-time jobs around the world to automation if it lives up to its promised capabilities.

The report, written by Joseph Briggs and Devesh Kodnani, said that roughly two-thirds of current jobs are exposed to some degree of AI automation while generative AI could substitute up to a quarter of current work.

White-collar workers are some of the most likely to be affected by new AI tools. The Goldman report highlighted US legal workers and administrative staff as particularly at risk from the new tech. An earlier study from researchers at Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and New York University, also estimated legal services as the industry most likely to be affected by technology like ChatGPT.

Manav Raj, one of the authors of the study, and an Assistant Professor of Management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, told Insider this was because the legal services industry was made up of a relatively small number of occupations that were already highly exposed to AI automation.

Goldman’s report suggested that if generative AI is widely implemented, it could lead to significant labor cost savings and new job creation. The current hype around AI has already given rise to new roles, including prompt engineers, a job that includes writing text instead of code to test AI chatbots.

The new tech could also boost global labor productivity, with Goldman estimating that AI could even eventually increase annual global GDP by 7%.

For the first time ever, women CEOs now make up more than 10 percent of Fortune 500 leaders. But that’s hardly a reason to celebrate. On every indicator, white men still dominate the upper rungs of the economy, while women — particularly women of color — continue to be overrepresented in low-paying jobs. And even when women do break through the glass ceiling, they’re still part of a system…