Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf discusses his just-released book

Archive for category: #Capitalism #EconomicCrisis #Finance

Hunger is expected to soar across the United States next month when more than 30 million people enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program see their food benefits slashed significantly.

“This hunger cliff is coming to the vast majority of states, and people will on average lose about $82 of SNAP benefits a month,” Ellen Vollinger, director for SNAP at the Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), told CBS News on Friday. “That is a stunning number.”

As the outlet reported: “That means a family of four could see their monthly benefit cut by about $328 a month. The worst-hit could be elderly Americans who receive the minimum monthly benefit, Vollinger said. They could see their SNAP payments tumble from $281 to as little as $23 per month.”

Since a federal public health emergency was first declared at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, so-called emergency allotments have boosted food benefits nationwide.

Republican lawmakers in 18 states chose to eliminate their emergency allotments early. Many tried to justify the move by pointing to the recovery from the coronavirus-driven economic crisis, but research shows that demand at food banks has surged in states that spurned extra federal aid.

The remaining 32 states that have continued to provide enhanced food benefits will be forced to eliminate their emergency allotments in March because funding was cut in the 2023 omnibus spending package enacted in December.

States facing imminent reductions in food benefits include California and Texas, which have the most SNAP beneficiaries with 5.1 million and 3.6 million recipients, respectively. Meanwhile, New Mexico is home to the highest number of SNAP beneficiaries per capita, with more than 3 in 10 households currently receiving augmented food benefits.

As Insider reported Friday, state officials are now “scrambling to get the word out to residents that their benefits are being dramatically reduced.”

Gina Plata-Nino, deputy director for SNAP at FRAC, told the outlet that “the last thing you want is grandma Sue showing up to the grocery store all of a sudden like, ‘Where’s my money? This is what I had budgeted.”

“That’s the hunger cliff that we’re facing—that people had this budget, things haven’t gotten better, and now you’re going to a grocery store where things are more expensive,” said Plata-Nino.

“You’re going to see, as the months go along, more families being hungry, more people visiting food banks, and just seeing the terrible effects that this had on all of these people.”

While the U.S. economy is on stronger footing than it was in March 2020, households are now grappling with higher prices—especially for essentials like milk and eggs—due to unchecked corporate profiteering.

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, groceries cost about 10% more at the end of last year than they did 12 months earlier. The price of a gallon of whole milk climbed from $3.74 in December 2021 to $4.21 in December 2022, for instance, while the price of a dozen large Grade A eggs increased from $1.79 to $4.25 over the same time period.

Given the context in which looming SNAP cuts are set to unfold, “you’re going to see, as the months go along, more families being hungry, more people visiting food banks, and just seeing the terrible effects that this had on all of these people,” Plata-Nino predicted.

Millions of households nationwide continue to struggle with food insecurity. According to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, more than 41.2 million people were enrolled in SNAP in fiscal year 2022, a 15% increase over fiscal year 2019, when roughly 35.7 million received food benefits.

“It may seem like an oddity that SNAP enrollment has increased given that the nation’s unemployment rate is at its lowest since 1969, but many workers still can’t find full-time work or line up enough hours to pay the bills,” CBS News noted, citing Vollinger. “Most working-age people who receive food stamps are employed, research has found.”

Vollinger told the outlet that people are often unaware that “so many SNAP households are employed, but often employed at low-wage levels—they aren’t in jobs that are family-sustaining so they still qualify for SNAP.”

As Insider reported: “Some states are stepping in to try and fill the gap left by the end of beefed-up SNAP benefits: New Jersey increased the minimum benefit that residents can receive, and Massachusetts is moving to try and keep payments higher for three months, albeit at 40% of what recipients get now.”

In other states that are simply sharing advice about how to cope with the pending cuts, such as stocking up on nonperishable items while food benefits remain higher, people are expressing anger.

“We are reducing your food stamps and we know you will have a hard time surviving so here are some tips,” one SNAP beneficiary in Colorado tweeted sardonically. “Don’t say we didn’t ever do nothing for you.”

In less than three weeks, bolstered SNAP benefits “will go the way of enhanced unemployment benefits, free school lunches, and the child tax credit,” Insider noted. “All provided a safety net and helped keep hunger at bay for many, but there is little legislative appetite to renew them.”

Other pandemic-era welfare state expansions—including increased Medicaid coverage and the free provision of Covid-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments—are set to end abruptly on May 11. That’s when the federal public health emergency, which the Biden administration has refused to extend further, is slated to expire.

Happy Friday eve to the smartest corner of the internet. Phil Rosen here, writing to you from New York City.

This week I’ve seen commentators draw comparisons between the current boom in artificial intelligence stocks and that of meme stocks two years ago.

But veteran market-watchers told me that beyond general budding enthusiasm, the two trends couldn’t be less alike. The fundamentals driving each surge are just about from different planets.

Here’s the takeaway: When it comes to AI names, investors won’t have to rely on goodwill from the Reddit crowd this time around.

But we’ve got meaner beasts to tackle today — starting with a global recession.

If this was forwarded to you, sign up here. Download Insider’s app here.

Alexander Spatari/Getty Images

1. Like most economic discussions, risks of catastrophe vary depending on who you ask. That’s where quantitative indicators can prove helpful.

Right now, the chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, Robin Brooks, is watching weakening commodity prices.

Specifically, Brooks pointed out that oil and copper prices have slumped roughly 6% each since mid-January, despite China’s easing of zero-COVID policies.

“Whatever is going on in China, there’s no sign that the end of zero-COVID is boosting global growth, based on commodity prices,” Brooks said in a tweet. “Oil prices never went up and copper prices are falling after the initial China reopening excitement fades.”

And he closed with a brief but powerful warning:

“Global recession is coming.”

Craig Erlam, an analyst at OANDA, told my colleague in London, Zahra Tayeb, that the oil and copper declines suggest lingering anxiety about economic risks, and that markets could be factoring in slower growth elsewhere.

But then again, that weakness could also be a reflection of higher interest rates around the world resulting in reduced liquidity in the financial system.

“No shadow of a doubt, there is no depth to markets (bid offer spreads widening, and depth and number/size of market bids/offers below current prices),” Marc Ostwald of ADM Investor Services told Insider.

He pointed to the sharp change in oil prices last week as an example of shallower liquidity.

To him it comes down to a financial problem, not a problem of supply.

“As witnessed in oil prices round trip on Friday, if there was liquidity, the market does not do round trips like that — the same thing applies to copper and Treasuries,” Ostwald said.

How has your investing strategy changed as recession calls heat up? Tweet me (@philrosenn) or email me (prosen@insider.com) to let me know.

In other news:

US gas prices have cooled off sharply over the last month.

2. US stock futures rise early Thursday, following a number of better-than-expected earnings reports. Meanwhile, investors are watching for the latest data on weekly unemployment claims, due out at 8:30 a.m. ET. Here are the latest market moves.

3. On the docket: PepsiCo, L’Oréal, and Toyota, all reporting.

4. The AI craze has sent some stocks soaring up to 300%. One expert predicted that apps like ChatGPT could accelerate investor returns in the coming years. The sector’s top fund managers shared the best 74 stocks to capitalize on the trend.

5. American drivers are using less gas as work-from-home persists. The EIA said Tuesday it expects that trend to continue, and the rise of electric vehicles will also curtail gas demand: “The heyday of gasoline is over.”

6. Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel explained why he blames the Fed for inflation. In an interview with Insider, the veteran market-watcher slammed the central bank for fanning high prices, and warned that a recession could be on the way. Read his full insights.

7. Russia’s growing use of China’s yuan doesn’t pose a threat to the US dollar, according to a Washington DC-based think tank. If anything, that pivot could end up hurting the Russian economy. Here’s why the yuan’s growing overseas use isn’t going to bring down the greenback.

8. Dallas, Las Vegas, and other cities made Insider’s list of best markets for homebuyers in 2023. Housing prices continue to slide in the new year, and some economists have warned that a 20% decline is around the corner. See the list of 15 cities.

9. Wall Street investors are saying there’s never been a better time to invest money overseas. Goldman Sachs’ David Kostin said the firm’s global equity forecasts point to better return potential in non-US markets. Here are the seven best opportunities right now.

Disney stock price on February 9, 2023

10. Disney stock surged after hours Wednesday after the company announced plans for layoffs. Newly returned Bob Iger has decided to slash 7,000 jobs and reorganize the company — which investors have cheered.

Curated by Phil Rosen in New York. Feedback or tips? Tweet @philrosenn or email prosen@insider.com

Edited by Max Adams (@maxradams) in New York and Hallam Bullock (@hallam_bullock) in London.

Standing Up

Billionaire Microsoft cofounder, philanthropist, and climate advocate Bill Gates will do whatever it takes to save the planet — as long as it doesn’t mean flying economy.

“Well, I buy the gold standard of, funding Climeworks, to do direct air capture that far exceeds my family’s carbon footprint,” Gates told the BBC during a lengthy interview, when asked how he feels about the criticism that, as one of the world’s premier voices in the climate movement, regularly flying private — widely regarded as one of the more blatantly terrible things one can do for the environment — is a bit hypocritical. (To clarify, Climeworks is a direct air carbon capture firm that has a partnership with the Gates-founded Microsoft.)

“And I spend billions of dollars on… climate innovation,” he added. “So, you know, should I stay at home and not come to Kenya and learn about farming and malaria?”

In other words, Gates says that because of all that he already does for the world, his carbon footprint is offset enough that it’s A-OK for him to fly private any time he pleases.

The billionaire also said that he’s “comfortable with the idea that, not only am I not part of the problem by paying for the offsets, but also through the billions that my Breakthrough Energy Group is spending,” referring to his alternative energy-focused investment fund, “that I’m part of the solution.”

Of course, he could very well offset even more carbon if he chose to put the private jet away and, on occasion, humbly opt for first class. But we digress.

One Percenters

Gates isn’t the only famous climate advocate to be hit with similar criticisms.

Elderly babysitter Leonardo DiCaprio, whose entire Instagram is devoted to his environmentalist efforts, has been criticized for his love of yachting, another activity known to be pretty awful for the environment, while Amazon founder and Bezos Earth Fund creator Jeff Bezos is often criticized for his own private jet use as well. (And also, uh, for how generally horrible Amazon is for the planet.)

To Gates’ credit, he does do a lot for the environment, and there are legitimate practical reasons why ultra-wealthy folks might want to fly private. Still, it’s always nice to see those at the top set positive examples for others in their tax bracket, considering how disproportionate the top one percent’s climate impact really is.

READ MORE: Bill Gates on why he’ll carry on using private jets and campaigning on climate change [CNBC]

More on Bill Gates: Bill Gates Gives $12 Million to Flatulent Australian Cows

The post Bill Pledges to Keep Flying Private Jet While Speaking Out Against Climate Change appeared first on Futurism.

“The theories of John Maynard Keynes provide the sound intellectual framework for the views which trade unionists had always instinctively held and known to be right” (TUC, 1968, p. 85)

The ideas and theories of John Maynard Keynes still dominate the economic views and policy proposals of the leaders of the labour movement in the major capitalist economies. Keynes is seen as offering a ‘third way’ between the pro-capitalist ‘free market’ economics that dominates the universities (and among the strategic advisers of government) and the opposite of dangerously revolutionary Marxian economics. Keynes argued that, with a judicious range of policy measures, capitalism can be made to work better and can be managed so that it meets the needs of the many, without disrupting the social structure of society.

On this blog and elsewhere, I have developed a long and detailed critique of Keynesian economics. But suffice it to say now that free market economics claims that prosperity will be achieved as long as capitalists are free of any regulations (environmental, safety, health etc) and of too much taxation, while markets are kept ‘competitive’ and free of monopolies, particularly in the ‘labour market’ ie. trade unions. Then capitalists can compete freely to maximise profits and in doing so will invest in new technology to boost the productivity of labour and employ more workers, whose wages will then rise. Everybody wins.

The Keynesians retort that free market capitalism (‘laisser-faire economics’, Keynes called it) does not work because the market economy has faultlines that generate a chronic lack of ‘effective demand’. Holding down wages to boost profits means capitalists cannot sell all their production and are periodically forced into laying off workers and unemployment ensues. It is necessary for governments to intervene and raise wage levels and/or increase government spending to fill the gap in aggregate demand. Then this will create enough demand for capitalists to sell their goods and make a profit. So a judicious macro management of the market economy can work for all.

The Marxist view is that it is not question of the lack of demand or low wages or inequality in the distribution of incomes, but a problem in the profit system of production itself. The contradiction of capitalism is that, despite the efforts of capitalists, average profitability will fall over time. This causes recurrent and regular crises of production that cannot be resolved by the ‘free markets’ or Keynesian macro-economic management.

This Marxist view carries little traction among economists and leaders of the labour movement. The dominance of the Keynesian thought among the ‘left’ and in the labour movement was expressed most clearly in the UK only last week in a report by the British Trade Union Congress (TUC) on the state of the UK economy and what to do about it.

The report was authored and presented by Geoff Tily, a senior TUC economist. Tily is a long standing and enthusiastic follower of Keynes, whose work he considers as being radical and pertinent to solving the problems of the 21st century capitalism. His book ‘Keynes Betrayed’ is regarded as one of the most prominent in arguing that Keynes was a radical reformer of market economics and economies.

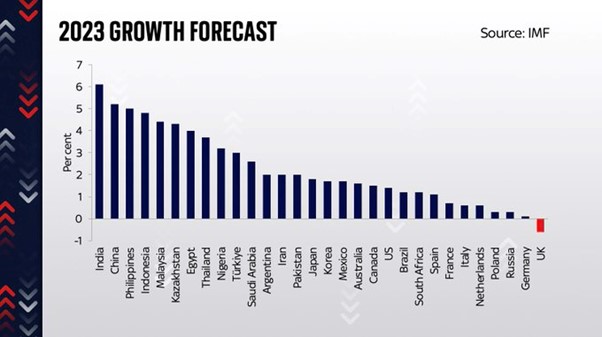

The TUC report offers a powerful account (with facts and figures) of the shocking failure of British capital. The British economy is now not only regarded as ‘the sick man of Europe’ but of the G7 and indeed of the top 30 economies in the world , at least according to the IMF, which reckons it will be the only major economy to enter a slump this year.

The TUC report describes the UK economy as in a ‘doom loop’, a term used by the current Labour spokeperson on economics, Rachel Reeves: “This government has forced our economy into a doom loop – where low growth leads to higher taxes, lower investment, squeezed wages, and the running down of public services. All of which hit growth again”, Rachel Reeves, response to Autumn Statement, 17 Nov. 2022. According to the ‘doom loop’ argument, the vast erosion of around a third of the UK economy and the arrested standard of life for workers is a consequence of the fiscal ‘austerity’ policies in place since 2010. The TUC report refers to former Marxist (now Keynesian) Paul Mason who explains the loop: “supply is deficient, but the immediate cause of this deficiency is aggregate demand. This means that policymakers over 2022 and into 2023 are intensifying contractionary policy in the face of deficient aggregate demand.“

So the failure of British capital is down to the austerity policies since 2010 of cutting government spending creating a lack of demand. What happened to British capital before 2010 is ignored. The policy answer is to reverse austerity, raise government spending and wages and then aggregate demand will rise through what is called the Keynesian multiplier and so restore economic growth. “With these mechanisms identified, the lost prosperity can be restored.”

The TUC report criticises those on the left who reckon the current crisis is due to supply constraints. Instead, “what is wrong is that existing capacity and resources are being underused and not that we just need to invest for more capacity.” The TUC report refers here to a piece by another former Marxist turned Keynesian, James Meadway, who argues that it is not a zero-sum game between expanding capacity (supply) and raising demand for existing capacity. Keynesian theory “reinforces the empirical judgement that there is vast underutilised potential that can be deployed through current as well as capital expenditures…. So the core of a left strategy today – including its programme for the environment – is redistribution.” (Meadway). I interpret this to mean that it is not necessary to replace the capitalism mode of production but just make the redistribution of income and wealth fairer and the economy will jump forwards.

The Guardian newspaper editorial described, in its paeon of praise, that the TUC report “draws heavily on the recent ‘New macroeconomics’ literature, that in turn recalls the historic contributions of J. A. Hobson (1858-1940) and J. M. Keynes (1883-1946). These emphasise the relation between a too high return to wealth and too low return to work, and theories of over-production and underconsumption. Rather than deficient supply, the underlying problem of the world economy is excessive supply in the context of deficient demand.” Really – excessive supply!

As the TUC report puts it, the problem is that the “excessive imbalance towards wealth from labour distorts economic activity through a dislocation between aggregate production and aggregate purchasing power. On the one hand, too low wages put goods and services out of the reach of workers. On the other hand, the massive resources of the wealthy do not compensate because they are relatively less interested in goods and services …. Consumption therefore falls short and overproduction is the result.”

Thus Tily presents us with an unvarnished theory of crises based on underconsumption. As he says, the logic of his argument “leads to the vital conclusion that underconsumption and overproduction are relative conceptions: production is only excessive relative to deficient purchasing power and pay. It therefore follows that a better balance between labour and capital will permit higher production in an absolute sense. The analysis has always appealed to the left, above all motivating the 1945 Labour Manifesto: over-production is not the cause of depression and unemployment; it is under-consumption that is responsible (my emphasis)”.

This crude underconsumption theory of crises was refuted by Marx 160 years ago and has been proven wrong empirically over time. It is not even strictly Keynes’ theory. But it is apparently the bedrock of the current TUC analysis. What is the cause of this chronic underconsumption? According to Tily, it is that investment cannot expand capacity if interest rates, the cost of borrowing, are too high. Keynes showed that it is high interest rates set by finance capital that weakens productive capital, not the underlying profitability of productive capital. As Tily puts it: “The focal point of his analysis and much of his practical work was securing a permanent reduction in the long-term rate of interest.” Indeed, ending the rule of finance capital altogether, “the euthanasia of the rentier” as Keynes called it.

How this was to be achieved given the expanding role of finance capital in modern economies is not made clear. Reforming the finance sector through ‘regulation’ is apparently the policy measure. Good luck with that! The TUC and Tily never advocate the public ownership of the big banks and the closure of speculative hedge funds and investment banks. Such policies are taboo.

Moreover, how do we explain why the very low interest rates that Britain has enjoyed in the last 20 years have not led to faster investment and growth in the productive sector? Tily’s answer is that “a distinction should be made between Keynes’s low interest rate polices and the manner of monetary policy over the past decade. Keynes sought low interest rates above all to strengthen fixed capital investment, and he envisaged domestic action in the context of capital control on the international domain. Low interest rate policies today are in the context of an utterly deregulated global regime. Rather than foster domestic production, low rates have been recycled to earn high reward on more speculative terrain.”

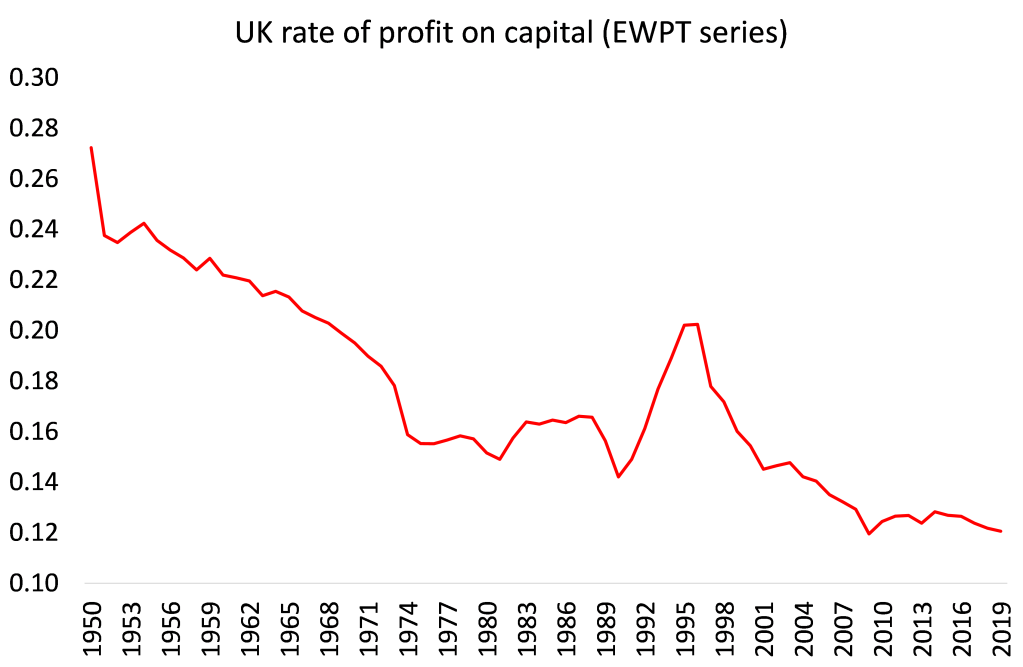

Maybe so, but that still begs the question : why this time has cheap credit been ploughed by banks and big business into financial speculation and not into productive investment (as, according to Tily, it was in the Golden Age)? The reason surely is that now it is more profitable to do the former than to do the latter. In the golden age after WW2, profitability was high in the productive sectors and the financial sector was not dominant. It is the fall in profitability that has led to the switch to financial speculation.

Interestingly, Tily slightly retreats from his view that it is Keynes’ theory on interest rates rather than profitability that provides the explanation of crises, when he admits that “on theoretical grounds the (supply-side) idea of a falling rate of profit may still be persuasive and regarded as vindicated by productivity outcomes on a long horizon.”

And Tily goes on to admit that Keynes was no radical reformer as he claims, being strongly opposed to Marxian economics. “Keynes was on the record making stupid remarks, for example in his (1925) ‘A short view of Russia’: “How can I adopt a creed which, preferring the mud to the fish, exalts the boorish proletariat above the bourgeois and intelligentsia who, with whatever faults, are the quality in life and surely carry the seeds of all human advancement?” (CW IX, p. 258) Indeed, Keynes refused to support the Labour party in the 1930s, siding with the Liberals because Labour was “a class party and the class is not my class. The class war will find me on the side of the educated bourgeoisie.”

As for supporting wage increases to solve crises, Keynes was not so keen on boosting wages as a solution to a slump. “in general, an increase in employment can only occur to the accompaniment of a decline in the rate of real wages. Thus, I am not disputing this vital fact which the classical economists have (rightly) asserted as indefeasible.” Indeed, Keynes in his later years increasingly emphasised the correctness of ‘free market economics, what he called ‘classical economy’. “I do not suppose that the (neo) classical medicine will work by itself or that we can depend on it. We need quicker and less painful aids. But in the long run, these expedients will work better and we shall need them less, if the classical medicine is also at work. And if we reject the medicine from our systems altogether, we may just drift on from expedient to expedient and never get really fit again.” Keynes 1940.

This is what Keynes said in his last years: “If our central controls succeed in establishing an aggregate volume of output corresponding to full employment as nearly as is practicable, the classical theory comes into its own again from this point onwards.” So once full employment is achieved, we can dispense with planning and ‘socialised investment’ and return to free markets and mainstream neoclassical economics and policy: “the result of filling in the gaps in the classical theory is not to dispose of the ‘Manchester System’ (‘free’ markets – MR), but to indicate the nature of the environment which the free play of economic forces requires if it is to realise the full potentialities of production.”

When arch free marketeer Friedrich Hayek published his book, The Road to Serfdom, which preached that state control would end ‘democracy’ and the freedom of the market economy, Keynes wrote to Hayek: “morally and philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it; and not only in agreement with it, but in a deeply moved agreement.”!

As he concluded: “For the most part, I think that Capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organisation which shall be as efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life.” The profit motive must remain: “The loss of profit may be due to all sorts of causes, but short of going over to communism there is no possibility of curing unemployment except by restoring to employers a proper margin of profit.” As Keynes argued that “Economic prosperity is…dependent on a political and social atmosphere which is congenial to the average businessman.” These are hardly comments of a radical reformer.

Tily and the batch of Keynesian economists who spoke at the presentation of the TUC report always refer back to the golden days of the 1960s when supposedly Keynesian policies were working and a prosperous economy was being achieved through management of the economy. But this is a myth. The 1970s saw rising unemployment and inflation, alongside falling profitability of capital. How was that possible if Keynesian policies were so successful?

In contrast to Keynes, Marx said that the key to understanding the capitalist mode of production lay in the nature of production to sell commodities on a market for profit. Profit was the key. Now capitalists have to use some of that profit to pay interest on loans or rent on property and, if these ‘rentiers’ (bankers and landowners) squeezed the profit-holding capitalist too far, sure, they could cause a crisis in investment. But even if interest rates are low or zero and even if rents are low or zero, there would still be crises, slumps and depressions. Why? Because rent and interest and profit come from surplus value, not the other way round.

Keynes and Tily say the crisis comes about through a lack of ‘effective demand’, namely an unaccountable fall in investment and consumption and this causes profits and wages to fall. Marx says: let’s start with profits. If profits fall, then capitalists would stop investing, lay off workers and wages would drop and consumption would fall. Then there would be a lack of effective demand, as Keynesians like to put it, but this would not be due to a drop in ‘animal spirits’, or ‘confidence’ (we often hear that phrase from economists, ‘a lack of confidence’), or even due to ‘too high’ interest rates, but because profits are down. The problem lies in the nature of capitalist production, not in the finance sector alone.

Policies designed to reduce interest rates, or even get some government spending going, namely Keynesian policies, would not avoid these slumps or even get recovery going. Indeed, more spending on welfare and unemployment benefits could drive up taxes and extra borrowing could drive up interest rates. And more government investment that replaced or encroached on private sector investment could be damaging to the profitability of capital. So Keynesian policies could even delay economic recovery.

Indeed, the austerity policies of most governments are not as insane as Keynesians think. Austerity policies are perfectly rational: they follow from the need to drive down costs, particularly wage costs, but also taxation and interest costs, and the need to weaken the labour movement so that profits can be raised. It is a perfectly rational policy from the point of view of capital, which is why Keynesian policies were never introduced to any degree in the 1930s.

Marx’s analysis shows that the capitalist system is not just suffering from a ‘technical malfunction’ in its financial sector (due to high interest rates), but has inherent contradictions in the production sector, namely the barrier to growth caused by capital itself. What flows from this is that the capitalist system cannot be reformed or corrected in order to achieve sustained economic growth without booms and slumps – it must be replaced. That is the ultimate policy action for the left.

Lintao Zhang/Getty; Anna Moneymaker/Getty; Katsumi Murouchi/Getty; Anna Kim/Insider

- The Chinese yuan poses a threat to US dollar dominance, according to Nouriel Roubini.

- He predicted in a Financial Times column the emergence of a bipolar currency regime.

- “The intensifying geopolitical contest between Washington and Beijing will inevitably be felt in a bipolar global reserve currency regime as well.”

The US dollar is facing a threat from the Chinese yuan and the end of its dominance in the global financial system, according to Nouriel Roubini, chief economist at Atlas Capital Team.

In a Financial Times column on Sunday, Roubini said that as the world becomes ever more split between US and Chinese influence, “it is likely that a bipolar, rather than a multipolar, currency regime will eventually replace the unipolar one.”

The so-called Dr. Doom economist, who is noted for his dire predictions, said that while skeptics typically caution that China’s stiff currency controls should prevent the yuan from overtaking the dollar, the US has its own version that “reduce the appeal of dollar assets among foes and relative friends.”

“These include financial sanctions against its rivals, restrictions to inward investment in many national security-sensitive sectors and firms, and even secondary sanctions against friends who violate the primary ones,” Roubini wrote.

Last year, the US and its Western allies froze Russia’s foreign exchange reserves and kicked it out of the SWIFT financial system. In addition, the Biden administration has sought to cut off China’s access to key technologies and investment that could aid its military.

Other attempts to erode the dollar’s dominance have also emerged recently, including Russia and China opening talks last year to develop a new reserve currency with other BRICS countries as well as an effort by Russia and Iran to create a cryptocurrency backed by gold.

Meanwhile, China and Saudi Arabia have already transacted for oil in yuan this past December, Roubini said, and “it is not farfetched to think that Beijing could offer the Saudis and other Gulf Co-operation Council petrostates the ability to trade oil in RMB and to hold a greater share of their reserves in the Chinese currency.”

The rise of a so-called petroyuan will gain momentum as China leverages its status as the world’s biggest oil importer, analysts have said separately.

In addition, Roubini predicted that the growing interest in central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs, will help accelerate dollar’s erosion as a global reserve currency over the next decade.

“The intensifying geopolitical contest between Washington and Beijing will inevitably be felt in a bipolar global reserve currency regime as well,” Roubini said.

On the other side of the argument, top economist Paul Krugman said investors shouldn’t lose sleep over potential threats to the dollar’s dominance. The Nobel Prize-winning economist said Friday in a New York Times op-ed that he’s not expecting to see the greenback unseated as the major currency for international trade anytime soon.

Compassionate Eye Foundation/Martin Barraud/OJO Images Ltd / Getty Images

- The US economy isn’t in a recession yet.

- But the tech, housing, and manufacturing industries might be already.

- The more industries that falter, the greater the odds the whole economy falls with them.

No, the US economy isn’t in a recession yet. But some of its key industries might be, suggesting the desired “soft landing” is far from a sure thing.

Bloomberg economist Anna Wong, for instance, recently put the chances of a US recession this year at 80%. But as more industries fall into downturns of their own, she said it could become increasingly difficult for the US economy to avoid the same fate.

“We have a manufacturing recession, a housing recession, a tech recession,” she said in a Bloomberg post last week. “Things are starting to add up.”

It’s possible, however, that the US simply experiences a “rolling recession,” Loyola Marymount University finance professor Sung Won Sohn told CNBC. In this scenario, parts of the economy would “take turns suffering rather than simultaneously” — and the broader economy would never reach recession status.

Recent GDP and retail sales figures point to a slowing but still-growing economy, and economists say the US could enter a recession in 2023. That said, the labor market is still shockingly good, with the US adding a surprisingly large 517,000 jobs in January and seeing the lowest unemployment rate since 1969. Jobless claims figures over the past month remain low despite layoffs in Big Tech.

If the US economy does ultimately fall into a recession, it will partially be because the following three industries dragged it down with them.

The Fed’s efforts to cool rising prices may have doomed housing

Ever since the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to combat inflation, experts knew it could be bad news for the housing industry. Rising rates have led to elevated mortgage rates which, in combination with already-high home prices, have dampened demand.

As early as last September, ING’s chief economist James Knightley told Insider the US housing market had entered a recession.

“We have only had one monthly fall in house prices but with more supply coming on the market at a time when demand is weakening rapidly implies that prices fall further,” Knightley said at the time, adding that home affordability was “stretched to the limit.”

Five months later, things haven’t improved much.

“The housing market is already in recession,” Fannie Mae’s Deputy Chief Economist Mark Palim told Insider, pointing to the “pretty dramatic declines” in home sales in recent months. Fannie Mae is projecting a roughly 7% decline in home prices over the next 24 months.

Home applications have risen in recent weeks as mortgage rates have fallen slightly, but Mortgage Bankers Association economist Joel Kan told Insider that homebuying activity “remains tepid.”

Americans cutting back spending is bad news for manufacturing companies

US consumers facing inflation and dwindling savings are spending less on goods. That’s bad news for the manufacturing industry.

On Wednesday, Reuters markets analyst John Kemp said in a column that US manufacturers “probably entered a recession” in the fourth quarter of last year, based on the new results of the monthly Institute for Supply Management Report. The index, a survey-based measure of activity across the sector, fell to its lowest level since March and April of 2020, and excluding these months, the lowest level since the Great Recession in June of 2009. In December, PMI, another indicator of manufacturing activity, fell to its lowest level since May of 2020.

While the manufacturing industry has avoided widespread layoffs thus far, Kemp attributed this in part to “labor hoarding,” or a hesitancy from business to let workers go after having a difficult time attracting labor over the prior year.

The industry hasn’t been entirely unscathed by layoffs either. 3M, for instance, recently announced it was cutting 2,500 manufacturing roles across the globe.

Tech companies have led the way with layoffs

If any area of the economy is going through some challenges, it’s the tech industry.

In 2022, tech companies like Meta and Twitter laid off roughly 150,000 workers across the globe. While this fell far short of the two million workers let go during the dotcom bubble of 2001, it was well above the roughly 65,000 workers laid off in the sector during the worst years of the Great Recession.

Layoffs have come full speed ahead so far in 2023. There were over 55,000 reported tech layoffs during the first 20 days of January, more than the entire first half of 2022.

The industry’s struggles have been driven by a myriad of factors, including rising interest rates and slowing advertising demand. It’s led some to declare that a “tech recession” is already upon us.

The layoffs, in particular, however, can partially be attributed to companies scaling up their workforces too quickly.

When the pandemic took hold, and Americans flocked to streaming entertainment, at-home fitness, food delivery, and ecommerce, many companies thought this shift would be a permanent acceleration — and hired in mass as a result. But today, businesses in these industries are reckoning with the possibility they got a bit ahead of their skis.

It’s why despite significant job cuts, companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet still have significantly more workers than they did a few years ago.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

- The US stock market could face collapse by 2050, according to new research by a Finnish economist.

- That’s because US stock growth is unsustainable, and a crash is bound to happen in the coming decades.

- The findings of the study mirror recent commentary from Wall Street legends, who are warning of an epic wipeout.

The next few decades could bring on an epic stock market collapse, according to a Finnish economics professor and researcher from the University of Vaasa who’s sounding the alarm over an “armageddon” financial crisis.

In a recent paper titled “Armageddon of Financial Markets: Is the US equity market eventually going to collapse?”, Klaus Grosby pointed to extraordinary events that have rattled markets over the past decade, including the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war, which rocked global financial markets since last year.

Those stressors have all had “dramatic” impacts on the world economy, Grosby said, disrupting supply chains and spawning high inflation that central bankers are still trying to control. So far in the US, the Fed has hiked rates 450 basis-points to fight inflation. But when combined with ballooning levels of US debt, central bankers could be forced to choose between relieving debt burdens or stamping out high prices, economists warn, meaning a severe recession and stock market crash could be on the horizon.

Grosby’s paper re-examined past studies of stock market crashes to determine if another cataclysm was headed for the US market. Specifically, he referred to a 2001 paper that concluded that the US stock market was growing at such a rate it was headed for “finite-time singularity” – meaning growth is unsustainable, and will eventually lead to an “apocalyptic collapse” in stocks.

The 2001 paper pulled 1790-1999 data from the Dow Jones 30 Index. Using a model that detects faster-than-exponential growth to identify stock market bubbles, the researchers concluded that the US equity market was headed for a collapse in 2052.

Grosby tinkered with the same model using stock market data from the S&P 500 over the past twenty years, which would account for the dot-com bust, the 2008 crisis, as well as the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, which all led to a steep drop in the stock market. He also re-calibrated the model, as other analyses show it could be overestimating the time it takes for a stock market crash to occur. That could be due to the “extreme monetary policies” of the central bank in previous years, which Grosby speculates could accelerate the onset of a financial crisis. He compared the coming crash to the events of 1987 and 1929.

“The stock market crashes of October 1987 and October 1929 which were investigated in the current research as robustness checks might serve as a guide of how such a collapse could evolve: For both events, market participants observed extreme reductions in market capitalization in a very short time,” Grosby warned.

His findings echo warnings from prominent Wall Street commentators, who say disaster looms over the stock market. Legendary investor Jeremy Grantham warned investors last week of a “stomach-churning” crash that could wipe away 50% from the S&P 500. Ex-Bridgewater CEO Ray Dalio has warned repeatedly that financial markets are headed into a new world order – and after the Fed’s latest rate hike, interest rates this high could easily spark a severe recession and a 20% plunge in stocks.

Getty

- Elon Musk, Michael Burry, and Jeremy Grantham foresee potential pain for stocks and the economy.

- “Black Swan” specialists Nassim Taleb and Mark Spitznagel also see a tough road ahead for investors.

- Rising interest rates are exerting pressure on US asset prices and the economy.

Elon Musk, Michael Burry, and Jeremy Grantham are bracing for stocks to tumble and the US economy to slump into recession.

“The Black Swan” author Nassim Taleb and Universa Investments’ Mark Spitznagel, who specialize in protecting portfolios against unpredictable events with extreme impacts, also expect asset prices to plummet and a painful downturn to take hold.

Here’s a roundup of these 5 experts’ latest warnings:

1. Michael Burry

Burry is one of a handful of people to predict and profit from the collapse of the mid-2000s housing bubble. He tweeted a single-word message to investors this week: “Sell.”

The fund manager of “The Big Short” fame has compared the S&P 500’s rebound this year to the benchmark’s short-lived rally during the dot-com boom. He’s previously cautioned the index could plunge over 50% from its current level to below 1,900 points, and suggested a multiyear US recession is a virtual certainty.

2. Jeremy Grantham

Grantham acknowledged the significant scale of the market selloff last year in his latest research note, but noted the pain may not far from over.

“While the most extreme froth has been wiped off the market, valuations are still nowhere near their long-term averages,” the market historian and GMO cofounder said.

“If something does break and the world falls into a severe recession, the market could fall a stomach-turning 50% from here,” he continued. “At best there is likely to be at least a further modest decline.”

The veteran investor said the S&P 500 would most likely drop 23% to around 3,200 points this year or next, and spend some time below that level. He also suggested the index could plunge 50% in real terms from its peak at the start of 2022.

3. Elon Musk

Musk raised the prospect of a severe economic downturn during Tesla’s latest earnings call, and warned fear could send stocks spiraling downward.

“We’ll probably have a pretty difficult recession this year,” he said. “When there’s a recession and people panic in the stock market, then the value of stocks can drop sometimes to surprisingly low levels.”

The Tesla, SpaceX, and Twitter CEO has advised people to navigate the tough road ahead by conserving cash, avoiding debt, and taking fewer risks.

4. Nassim Taleb

Stocks soared after the financial crisis due to near-zero interest rates, which made it easy for companies to fuel their growth with cheap debt, and secure inflated valuations from cash-rich investors with few better options. However, the Federal Reserve has now hiked rates to nearly 5% in a bid to curb historic inflation, worsening the market backdrop.

Taleb, a Universa adviser and statistics guru, made that argument to Bloomberg this week.

“The stock market is way too overvalued for interest rates that are not 1%,” he said. “I think that we may have a collapse in many, many prices.”

“It doesn’t rain money anymore,” Taleb continued. “Disneyland is over.”

5. Mark Spitznagel

Spitznagel predicted massive economic and financial fallout, after years of freewheeling government spending and rock-bottom interest rates.

“It is objectively the greatest tinderbox-timebomb in financial history — greater than the late 1920s, and likely with similar market consequences,” he said in a letter to investors viewed by Bloomberg.

The Universa chief, who previously ran the now-defunct Empirica Capital hedge fund with Taleb, warned of a looming downturn that could have disastrous consequences.

“The correction that was once natural and healthy has instead become a contagious inferno capable of destroying the system entirely,” he said.