Right-wing Christian blogger and media figure Rod Dreher has moved to Hungary, where he continues…

Right-wing Christian blogger and media figure Rod Dreher has moved to Hungary, where he continues…

Preacher and former GOP Arkansas lawmaker, Jason Rapert’s organization, the National Association of Christian Lawmakers (NACL) is leading the charge on influencing the enactment of laws that enforce Christian nationalist ideology in state legislatures across the country, Rolling Stone reports.

Per Rolling Stone, as the “first-of-its-kind organization” since the United States’ inception, NACL specifically pushes “biblical” bills — legislation that cannot be identified as “mere stunts or messaging,” but “dark, freedom-limiting bills that, in some cases, have become law.”

Additionally, the former lawmaker noted that the organization is at “‘the forefront of the battles to end abortion in the individual states’ and also seeks to drive queer Americans back into the closet.” He said, “for far too long, we have allowed one political party in our nation to hold up Sodom and Gomorrah as a goal to be achieved rather than a sin to be shunned.”

As Rapert confirmed to Rolling Stone, “NACL was the first and only para-legislative organization in the country to adopt the Texas methodology as a model law, and we promoted it to be passed in every state.”

Rapert tweeted last year that “Sodom and Gomorrah idolized by the United States Government as directed by the #DEMOCRATS in control of our government. This is an embarrassment and defiles the history of our nation. I will never cease fighting to save our country from these mockers of all that is righteous.”

Rolling Stone reports:

As a matter of policy, NACL members must pledge to ‘uphold the sanctity of human life’ from the ‘moment of conception’ to ‘natural death’; to define marriage as the ‘sacred union exclusively between one man and one woman’; and to oppose ‘unhealthy influences such as alcohol abuse, drug addiction, pornography, prostitution, violence, gambling and crime.’ Ironically, NACLs website is ‘Powered by GoDaddy,’ a web service firm that sells .sex and .porn domains.

Additionally, the conservative preacher, according to Rolling Stone, has stated on his show, Save the Nation, he is a “‘proud’ Christian Nationalist,” and “rejects that being a Christian Nationalist is somehow unseemly or wrong.”

Andrew Whitehead, author of Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, notes Christian nationalists “believe that this country was founded for Christians like them, generally natural-born citizens and white.”

The Guardian reports recent national survey taken by the Public Research Institute and Brookings Institution “found that a majority of Republicans in the U.S. ‘are sympathetic to’ Christian nationalism.”

Another survey also conducted by Politico and the University of Maryland discovered that “61 percent of Republicans would be in ‘favor’ of ‘the United States officially declaring the United States to be a Christian nation.'”

Likewise, Rapert believes the United States “was founded as a ‘Judeo-Christian nation.'” Rolling Stone reports the minister also “believes the moment the founding fathers ‘dedicated this nation to God’ that ‘Satan and his forces [have] put a target on the United States of America, trying to take us out.'”

Regarding the group’s influence on nationwide legislation, NACL pushed the United State Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade last year. According to Rolling Stone, organization member and GOP Texas lawmaker, Bryan Hughes, spearheaded “the bounty-hunter bill that all-but outlawed abortion in Texas by allowing private citizens to sue women who terminate pregnancies after six weeks, and their doctors, in civil court.”

Rolling Stone reports:

By the time that bill passed in Texas in Sept. 2021, it had been adopted by NACL as model legislation. The reproductive rights group NARAL later tracked copycat legislation in more than a dozen states. Rapert takes substantial credit for that spread: ‘NACL was the first and only para-legislative organization in the country to adopt the Texas methodology as a model law,’ he tells Rolling Stone, ‘and we promoted it to be passed in every state.’

READ MORE: Do right-wing evangelicals really want a ‘Christian nation’?

Rapert’s group boasts constituents in 31 states, in addition to “a dozen ‘model laws'” members can push forward in their state legislatures.

READ MORE: Why Marjorie Taylor Greene’s ‘troubling’ endorsement of Christian nationalism is an ‘urgent threat’

Rolling Stone’s full report is available at this link (subscription required). The Guardian’s report is here.

Antifascist researcher Spencer Sunshine offers a critical look at ecofascism and Peter Staudenmaier’s book, Ecology Contested.

The increasing embrace by White Supremacists of environmentalism, which they use to justify their racist ideologies—dubbed “ecofascism”—is on the lips of many today. This has been driven by its mention in the manifestos connected to White Supremacist massacres in El Paso, Texas and Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019; between the two, 74 were murdered. Additionally, the new interest paid by fascists in Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, also shows rising interest in this trend.

Because of this, historian and anarchist Peter Staudenmaier’s book is a timely reminder that ecofascism is not just not a new problem, but also one that provides a bridge between the far-Right and the Left and anarchists. His book is a call, in the best radical environmental style, to blockade that bridge and stop fascists from entering radical circles.

Since the early 1990s Staudenmaier has been associated with the Institute for Social Ecology (ISE). The school was co-founded in 1974 by anarchist theoretician Murray Bookchin, and is best known for promoting what he dubbed social ecology—a fusion of Hegelianized Marxism, classical anarchism, and ecological thought. But ISE members have also been some of the earliest to warn anarchists about the danger of Red/Brown politics, especially in the radical environmental movement.

For example, Staudenmaier co-authored the 1995 book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience with Janet Biehl. His half was one of the first treatments in English documenting the “green wing” of the original Nazi Party, clearly showing how the fascist embrace of environmentalism has a long history and impeccable pedigree. But—especially in the context of Bookchin’s occasionally injudicious, and sometimes downright vicious, attacks on rival radical environmental currents—Ecofascism was controversial when it was published. Today it stands as a prescient warning of what was to come.

(The term “ecofascism” itself is muddy because of the different ways it’s invoked. Staudenmaier, following the clear understanding of different far-Right factions which antifascist work requires, uses it to refer to genuine fascists who embrace environmentalism. Other leftists use it to refer to all right-wingers who oppose environmentalism. Meanwhile, many conservatives use it to smear environmentalists themselves!)

Ecology Contested is yet another warning about the thriving postwar ecofascist currents. In the increasingly crowded field of writings about this subject, Staudenmaier’s book stands out by its focus on the relationship between the Left and Right on environmentalism, but also anti-tech and animal rights politics. He does so by showing their overlapping theoretical, but also in some cases existing political, relationships. Like his 1995 book, Ecology Contested is sure to ruffle feathers. Some may even see it less as a warning of potential right-wing incursions and more as an attack on their own politics.

The five essays in this anthology were written over a period of two decades. The first and last ones, “The Politics of Nature from Left to Right” and “Blood and Soil Revived: Ecological Politics on the far-Right,” provide copious examples of the history of these ideas on the far-Right, from the 19th century on. He focuses on the notion of “blood and soil,” one of the main Nazi ideas the Alt Right later embraced (it was famously chanted in 2017 at Charlottesville) and which remains popular today.

In support of this, he documents a dizzying array of groups, spanning many decades and countries, which have embraced ecology and/or animal rights. Just some of these include both pre-and post-war Nazis and sympathizers in Britain and Germany (including Nazi agriculture minister Richard Walther Darré); crypto-fascist “National Anarchist” Troy Southgate; Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly Front National) in France; Casa Pound in Italy; the Nordic Resistance Movement in Sweden and Norway; and Golden Dawn in Greece. Last, U.S. groups include the multiple organizations in the Tanton Network, which influenced Donald Trump’s administration; the White Order of Thule; and Richard Spencer’s AltRight.com.

But still there are so many more examples. He does not address how a formerly imprisoned Earth Liberation Front activist, “Exile,” became an Evolian fascist. And he only mentions Dave Foreman, one of the founders of the radical environmental movement Earth First!, in the footnotes. Foreman embraced anti-immigration politics and was pleased about the mass deaths of Ethiopians during a major famine in the 1980s.

Staudenmaier’s short “Disney Ecology” from 1998 is aimed at misanthropic environmentalists who see nature as wild and pure, and humans as a cancer. Staudenmaier argues that this is a colonial viewpoint, a view that is widely acknowledged today. Rather than an ‘untouched’ wilderness discovered by Europeans, almost all of the areas seen this way had previously been occupied by indigenous people, who in turn formed and shaped the land—at least until their genocide.

But more importantly, the piece places front and center the nub of one of the book’s main arguments: Staudenmaier holds that notions of a purity that must be defended is a theme found on both the Left and the Right, and as such can link the two in disturbing ways. The answers he offers to the criticisms he makes here, and elsewhere in the book, all draw from social ecology. And so, depending on their own attitudes about this theoretical perspective, readers will likely find them either compelling or annoying

Social ecology sees humans and the natural world as inescapably intertwined. Following this insight, Staudenmaier argues that philosophically separating humans and nature makes for a wrong-headed theory at best, while at worst harmonizes with fascist views. The answer to all these problems is the neo-Hegelian dialectic which drives social ecology: If humans can acknowledge this reciprocal relationship, they have an opportunity to self-consciously create a social and ecological politics that brings (what only appear to be) two separate spheres into harmony.

The longest essay in Ecology Contested, “A Revolution Against Technology,” was written in 2005 and revised in 2019. (In the interest of transparency, I provided feedback on the original version). It plumbs the intellectual origins of Ted Kaczynski, dubbed the Unabomber, who was imprisoned after engaging in a bombing campaign based on apocalyptic, anti-technological politics. Living in a remote cabin in Montana, between the 1970s and ’90s his bombs killed three people and wounded about two dozen.

Staudenmaier wrote his investigation into Kaczynski’s thought at a time when there was a wide breadth of speculation on it. The reason for this uncertainty was because Kaczynski carefully hid his intellectual progenitors in his manifesto, “Industrial Society and Its Future,” which the New York Times published in return for him agreeing to stop his campaign.

The essay correctly dismisses the argument that the origins of Kaczynski’s thought are either in pure nihilism or leftist criticisms of modern industrial society. In particular, Herbert Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, one of the most popular books in the 1960s New Left and similar in approach to Bookchin’s early works, is defended from these accusations. Staudenmaier admits that there is “little direct evidence about what Kaczynski may have read,” and therefore “such hypotheses remain speculative.” Nevertheless, he places the origins of the manifesto’s ideas in the anti-tech and anti-modernist strains of German far-Right thinkers associated with the Conservative Revolutionaries, who directly preceded the Nazis. Of these, the primary culprits fingered are Ludwig Klages, Oswald Spengler, and Friedrich Georg Jünger, who together forwarded a “reactionary critique of civilization.” Staudenmaier claims that there are “too many telltale signs…to ignore Kaczynski’s debt to right-wing thought.”

Ultimately, Staudenmaier, like the others who tried to make sense of Kaczynski, was unable to decipher his theoretical pedigree—and for good reason. In a 2021 article, “The Unabomber and the Origins of Anti-tech Radicalism,” Sean Fleming relied on previously unavailable archival material to identify three main influences, two of which came out of left field. Fleming concluded that the “Manifesto is a synthesis of ideas from three well known academics: French philosopher Jacques Ellul, British zoologist Desmond Morris, and American psychologist Martin Seligman.” Ellul was the least surprising, and Staudenmaier did consider him as a possible influence, writing that wrote that his arguments were a “clear precursor” to Kaczynski. (However, Staudenmaier concluded that the differences between the two made the relationship inconclusive.)

Nonetheless, the evidence Staudenmaier marshaled to support his argument about the influence of reactionary politics remains important. Although Kaczynski occasionally called himself an anarchist, Staudenmaier foregrounds the right-wing nature of much of his thought, based on his own statements. This is especially important as Kaczynski has gained a following in the last few years among ecofascists, despite his own denunciation of them. According to Graham Macklin and Joshua Farrell-Molloy, ecofascists are drawn to him because his ideas reflect their interest in an anti-tech, völkisch worldview; a rejection of a modern decadent society through the use of violence; and anti-leftist views. He is frequently praised in writings and made into memes.

Staudenmaier foregrounds how Kaczynski sounds every bit like today’s Republicans who denounce an illusory notion of ‘antifa,’ using it as a catch-all to include everything from Nancy Pelosi to (post) insurrectionist anarchists. Kaczynski denounces the Left as a whole, a label which he says encompasses “socialists, collectivists, ‘politically correct’ types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists, and the like.” Staudenmaier points out that he also condemns “sexual perversion” and reserves “a special animosity for feminism.”

Staudenmaier also takes this opportunity to tie Kaczynski to three strands of anarchist thought he opposes: Stirnerite individualism, anti-leftism, and primitivism. Supporters and sympathizers who are named and shamed include Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed (AJODA), Bob Black, and of course John Zerzan, who championed Kaczynski after his arrest.

So while Staudenmaier’s speculative piece does not stand as intellectual history, it explains much about why Kaczynski’s thought has been embraced by a new wave of very online fascists. Here, Staudenmaier is convincing that, at least on social issues, Kaczynski easily has more in common with the ecofascist crowd then, say, anarcho-primitivists like Zerzan, who—and this is a good thing!—show their leftist origins by embracing feminism, sexual liberation, and anti-racism.

The book’s most contentious piece is undoubtedly “The Ambiguity of Animal Rights,” a critique of animal rights/animal liberation (he uses the two terms interchangeably), which received pushback even inside the ISE. The heyday of these politics among anarchists was in the 1990s, soon before the essay’s original publication in 2003. Staudenmaier recognizes this, and starts by taking great care to separate his intellectual critique from his respect for his comrades, including fellow social ecologists.

The piece is hampered by an uneven kitchen sink approach. Staudenmaier is critical of animal-rights narratives, describing them as politically confused. He condemns elements within the milieu for being liberal, self-righteous, anti-humanist, colonialist, racist, classist, Western elitist, parochial, and—perhaps the ultimate insult—phylumist (the privileging of animals with a central nervous system).

The essay would have been a much stronger if he had left most of these out and concentrated on two approaches. The first, as with the other essays, is his marshaling of historical examples of how fascists, including the Nazis but also latter day groups, embraced animal rights.

(My personal “favorite” of these was his recounting of the “hardline” subgenre of straight-edge hardcore; it brought back a flood of repressed memories of the Dayton, Ohio scene in 1993 and 1994. Hardline insisted on veganism, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, homophobia, and opposition to abortion; those in the scene also played terrible music and sported even worse fashion. It was rumored that hardline kids would roll drunk people leaving Dayton bars. True or not, it was definitely in the spirit of their approach.)

The second of approach which I found the most compelling was that animal rights draws a problematic line by attributing rights to certain animals while ignoring smaller living creatures like micro-organisms, as well as things that are commonly seen as ‘non-sentient,’ like trees, rocks, rivers, and ecosystems. From an ecological perspective, Staudenmaier rightfully points out the interconnection of all animals and organisms, a pillar of social ecology. Yet his answer falls short because he doesn’t present how social ecology would theorize or resolve the concerns of animal rights activists.

Overall, this short book—I read it in about five hours—is strongest as a warning about fascism’s environmental wing and its appeal to those outside its ideological quarters. It conclusively provides numerous examples for the unconvinced, and contains important warnings for activists who are not right-wingers but are enamored by figures such as Kaczynski. In particular, Staudenmaier’s careful discussion of the similarity between Kaczynski’s ideas and far-Right thought is illuminating, and even the animal rights essay raises a few good points. Last, Ecology Contested shows that Bookchin’s influence today is not solely limited to Rojava and direct democracy. As Staudenmaier so clearly illustrates, it extends into the realm of antifascism as well.

photo: Daniel Lincoln via Unsplash

We know all about the Russian plot to interfere in the 2016 elections, and at the same time to funnel millions of dollars to Donald Trump.

But the Russian scheme to pick our political leaders went much, much deeper than Trump, according to Dr. Ruth May. A Professor of Global Business at the University of Dallas and an expert on Russia, her expertise includes the reversal of market-based institutions in Russia under Vladimir Putin, and exposing Russia’s attack on our American democracy in the 2016 presidential election.

She explains how Vladimir Putin‘s right hand men arranged to have a river of dirty money flow into the pockets of top Republican senators, a certain infamous new member of Congress and other shady connections.

These are names you’ve definitely heard. But you may not have heard about their corruption at the hands of Russia, because the media can’t be bothered. Watch the video to see what Dr. May revealed about these GOP Senators. It’ll shock you, as will the media’s indifference to (or complicity in) burying this. They should be hitting these facts at every opportunity.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

A

t the small elementary school in Jouy-sous-les-Côtes, in northeastern France, Gisèle Marc knew the rumor about her: that her parents were not her real parents, and her real mother must have been a whore. It was the late 1940s, just after the war, a time when whispered stories like this one passed from parents to children. Women who were said to have slept with occupying soldiers—“horizontal collaborators”—had their heads shaved and were publicly shamed by angry crowds. In the schoolyard, children jeered at those who were said to be born of “unknown fathers.”

The idea that Gisèle might have been abandoned by someone of ill repute made her terribly ashamed. At the age of 10, she gathered her courage and confronted her mother, who told her the truth: We adopted you when you were 4 years old; you spoke German, but now you are French. Gisèle and her mother hardly ever talked about it again.

Gisèle found her adoption file, hidden in a drawer in her parents’ room, and from time to time she snuck a look at it. It contained little information. When she was 18, she burned it on the stove. “I said to myself, If I want to live, I have to get rid of all this,” she told me.

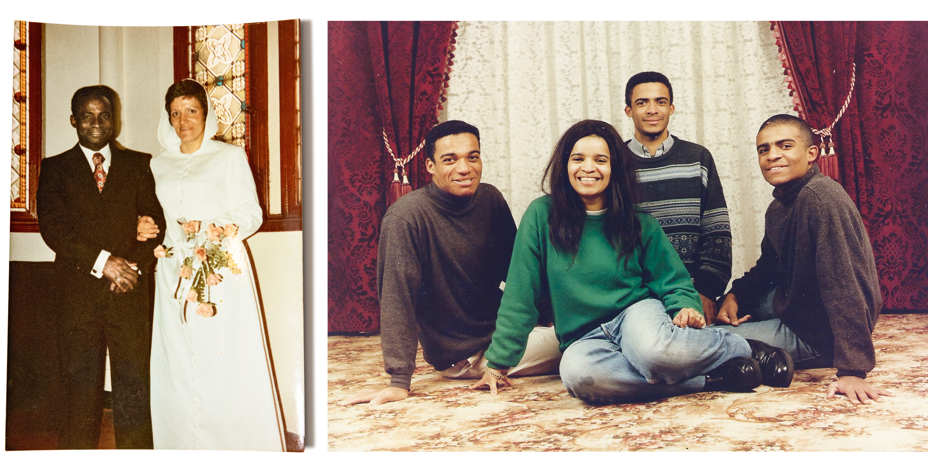

Gisèle is 79 now, and she does not regret burning the papers. For a time, she was able to put aside questions about her origins. At 17, she took a job in a children’s home and hospital and realized she had found her calling. She spent her career working mainly in day-care centers, and eventually founded her own. In 1972, she married Justin Niango, a chemistry student from the Ivory Coast. They bought an old hotel just behind Stanislas Square in Nancy and turned it into a house.

I visited Gisèle there in June. It was easy to imagine the vibrant family life that once took place inside: her children—Virginie, Gabriel, Grégoire, and Matthieu—running up and down the stairs and playing instruments in their rooms. At school, they were sometimes the only Black kids in their class. Gisèle has a lot of stories about the cruel comments made through the years; all the stories end with her confronting the culprit.

Gisèle at home in Nancy, France; a young Gisèle in Jouy-sous-les-Côtes, France (Nolwenn Brod for The Atlantic; courtesy of Gisèle Niango)

Gisèle held off on telling her children that she had been adopted, because she was worried that the revelation might weaken their bonds with her parents. Sometimes, though, the secret “burned a bit.” She knew she would share it eventually.

When her mother died, in 2004, she gathered her children and told them. They were shocked, and asked questions whose answers she did not know.

After years of denial, Gisèle longed to find those answers. She remembered the name and place of birth that had been listed in her burned adoption file: Gisela Magula, born in Bar-le-Duc, in northeastern France. She started her research there, and went on to write to the Arolsen Archives, the international center on Nazi persecution, in Germany, to ask if there was any mention of her in the organization’s extensive records.

In March 2005, Gisèle received a reply: She had not been born in Bar-le-Duc after all, but near Liège, Belgium, in a Nazi maternity home at the Château de Wégimont. That home and others like it had been set up by the SS, an elite corps of Nazi soldiers, under the umbrella of the Lebensborn association, through which the regime sought to encourage the birth of babies of “good blood” in order to hasten its ultimate goal of Aryan racial purity.

Everything Gisèle believed about herself wavered. The family she’d spent her adult life defending against racism, she realized, descended from one of history’s darkest racial projects.

N

azism was an ideology of destruction, one that held as its primary aim the elimination of “inferior races.” But another, equally fervent aspect of the Nazi credo was focused on an imagined form of restoration: As soon as they came to power, the Nazis set out to produce a new generation of pure-blooded Germans. The Lebensborn association was a key part of this plan. Established in 1935 under the auspices of the SS, it was intended to encourage procreation among members of the Aryan race by providing birthing mothers with comfort, financial support, and, when necessary, secrecy. The association’s headquarters were in Munich, in the former villa of the writer Thomas Mann, who had left Germany in 1933. In 1936, it opened its first maternity home, in nearby Steinhöring.

The SS was overseen by Heinrich Himmler, who hoped that its elite soldiers would serve as a racial vanguard for a revitalized Germanity. “As far as the value of our blood and the numbers of our population are concerned, we are dying out,” he said in a 1931 address to the SS. “We are called upon to establish foundations so that the next generation can make history.” An agronomist by training, Himmler supervised this undertaking with a level of attention that bordered on voyeurism; initially, all SS leaders’ marriage applications had to be referred to him. All were expected to reproduce: Four children was considered “the minimum amount … for a good sound marriage.” Himmler had no problem with childbearing outside marriage, and criticized the Catholic Church’s hostility toward illegitimate births. Raising “illegitimate or orphaned children of good blood” should be an “accepted custom,” Himmler wrote. In 1939, he issued an order that called on members of the SS to procreate wherever they could, including with women to whom they were not married.

According to Himmler, the Lebensborn homes were intended “primarily for the brides and wives of our young SS men, and secondarily for illegitimate mothers of good blood.” But the latter were, in practice, a majority. Far from the eyes of the world, single mothers could give birth in Lebensborn homes and, if they wanted to, abandon their babies, who would receive the best care before being placed in an adoptive family—so long as the biological parents met the racial criteria (photos of both were required). Early applicants had to meet a height requirement, and had to prove their racial and medical fitness going back two generations. The German historian Georg Lilienthal found that initially, fewer than half of the women who applied were accepted.

Lebensborn employees took note of how the mothers behaved during childbirth, and required them to breastfeed their children if they could. “The woman has her own battlefield,” Adolf Hitler said in 1935. “With every child she brings into the world, she fights her battle for the nation.”

Lebensborn babies in Germany, 1945 (Robert Capa / ICP / Magnum)

The women also received a daily “ideological education,” according to the historian Lisa Pine. Some of the babies were given a non-Christian first name by Lebensborn staff in a ceremony inspired by old Nordic customs. Under a Nazi flag and a portrait of the führer, in front of a congregation, the master of ceremonies would hold an SS dagger over the newborn and recite this creed: “We take you into our community as a limb of our body. You shall grow up in our protection and bring honor to your name, pride to your brotherhood, and inextinguishable glory to your race.” Through this ceremony, they believed, the child became a member of the SS clan, forever linked to the Reich.

By October 11, 1943, when Gisèle was born, there were about 16 Lebensborn facilities throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. She arrived four days too late to have Himmler as her godfather; the Reichsführer personally sponsored the children who shared his birthday, October 7.

One afternoon last spring, I sat with Gisèle in her living room, dozens of documents and photographs spread out before us. A short woman whose white hair is shot through with a streak of brown, Gisèle is at once reserved and straightforward, with a wry sense of humor. “Himmler really bungled with me,” she joked, referencing her marriage to an African man and their mixed-race family.

Gisèle’s wedding to Justin Niango, 1972; a Niango-family Christmas card (Courtesy of Gisèle Niango)

Gisèle rejects the idea that there’s a connection between her career and her early years spent in a very different kind of day care—she chose her path, after all, long before she knew where she had really come from.

Still, she doesn’t minimize the fact that her life story is inextricable from the history of Nazism. She has often wondered how her origins might shape what she calls her “internal memory”: She has always been terribly afraid of military trucks, trains, and leather boots. She cannot bear to hear babies crying; at her day care, she would often leave her office to comfort the little ones. She worries, too, that she somehow passed something evil on to her children through her genes.

A chance encounter helped Gisèle trace her origins. A few months after her mother’s death, just as she began her research, her cousin went to a funeral where a tall man with blond hair gave a eulogy for the departed, a teacher who had believed in him. The man, Walter Beausert, talked about his arrival in France as a child, in a convoy from Germany. Gisèle’s cousin, who was old enough to remember Gisèle’s adoption and knew that she’d come from Germany, struck up a conversation with Beausert after the funeral. Her cousin wondered whether Gisèle might have been in the same convoy.

Beausert was a Lebensborn child. A decade earlier, he had been the first person in France to testify about the Lebensborn, in a 1994 television report on his quest throughout Europe to find where he was born. Gisèle’s cousin put her in touch with Beausert, who soon helped Gisèle recover her own history.

Sisters of Mercy helped care for the displaced children at Kloster Indersdorf, including Gisèle (far left) and Walter (second from right). (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Lilo Plaschkes)

The story that Gisèle has pieced together is still full of holes, but she now knows the identity of her biological mother. Marguerite Magula was a Hungarian woman who immigrated to Brussels with her parents and sister in 1926. Marguerite eventually went to Germany to work, with her mother and sister, in a garment factory in Saarbrücken. When she got pregnant, in 1943, she ran away and returned to Brussels. Dorothee Schmitz-Köster, the author of Lifelong Lebensborn: The Desired Children of the SS and What Became of Them, told me that by then, the Lebensborn program had somewhat loosened its criteria: A fervent belief in National Socialism could make up for being short, as Marguerite was, though an Aryan certificate, a health certificate, and a certificate of hereditary health were still mandatory for both parents.

Gisèle’s feelings toward Marguerite have changed over time. When she learned from the Steinhöring archives that some mothers had searched for their children after the war, trying to get them back, Gisèle came to hate her. “She never sought me out,” Gisèle said. “I have no compassion, nothing; quite the opposite. That’s not a mother.” A postwar document denying Marguerite’s request for Hungarian citizenship (she and her sister were then stateless) mentions her “bad life.” Had Gisèle and Marguerite met, maybe she could have explained. But Marguerite died in 2001, just a few years before Gisèle began her search.

Gisèle has been less curious about the identity of her father; she imagines him as the stereotype of an SS officer—undoubtedly “a bastard.”

In 2009, Gisèle met a half brother, Claude, born after the war, who was raised by Marguerite. They still visit each other from time to time. Claude, she said, describes their mother as having mistreated him. He once told Gisèle she was lucky not to have grown up with their mother.

L

ike Gisèle, Walter Beausert owed the discovery of his origins to chance. At the birth of his first daughter, Valérie, in 1966, the midwife stared at Beausert, then 22 years old. Behind his helmet of straight blond hair, she noticed his light-blue eyes—one of them was a glass eye that never closed—and remembered the 17 small children who had arrived by train at the hospital in Commercy in 1946. “I think you come from Germany,” she said to him. It confirmed something Walter had always suspected.

Walter was the only child in that convoy to France never to have been adopted. He grew up in children’s homes and became a guarded, tough teenager. Unusually for a Lebensborn child, Beausert was circumcised. He never knew why. “My father was obsessed with the search for his family. He looked for his mother all his life,” Walter’s daughter Valérie, now 56, told me when we met at an old art-nouveau brasserie in Nancy.

Valérie Beausert; her father, Walter Beausert (Nolwenn Brod for The Atlantic; courtesy of Valérie Beausert)

In 1994, while filming the television report about the Lebensborn, Walter traveled to the site of the former Lebensborn home at the Château de Wégimont, where he heard from locals about a woman named Rita, a Lebensborn cook, who had had a baby boy named Walter. As German soldiers tried to take Walter away from Rita, the story went, he was dropped and his left eye was injured. This was the lead the grown-up Walter had been waiting for—Rita, he came to believe, was his mother.

“Except that’s not true,” Valérie said. “We met this Rita; we know who this Walter is. He’s not my father. But he didn’t want to hear anything about it. He said Rita had a second child who was also named Walter. I told him, ‘This doesn’t make any sense.’ His denial was pathological.”

Valérie, who has the same light-blue eyes and straight blond hair as her father, was called a “sale boche”—“dirty Kraut”—at school during her childhood, just as her father had been called a “white rat.” In 1986, Valérie fell in love with a man who was a refugee from Vietnam. “My son’s father was the first person of color in our village,” she said. “But for me it was a nonissue. I felt like an outsider myself.”

A young Walter; Walter and his grandson Lâm (Courtesy of Valérie Beausert)

Their son, Lâm, was born with one brown eye and one blue eye. One eye—the blue one—presented with a deficiency. The doctor identified a congenital abnormality that could cause blindness, which Valérie also carried and had passed on to him. Her father’s glass eye, she realized, was not the result of an injury at all. “When my son had to undergo an operation, I told my father, ‘You see, it is congenital.’” Her father was outraged, Valérie recalled: “Nonsense! You can’t say that!”

It wasn’t just that Walter wanted to believe that his glass eye was the result of his biological mother’s struggle to protect him from German soldiers; he was also terrified of disease, of being “a carrier of defects,” Valérie said, and went to great lengths to prove his superior strength and stoicism. One day, while he was chopping wood, his friend’s chainsaw ripped through a trunk, cutting both of Walter’s calves to the bone. Walter made himself two tourniquets and drove home. Valérie remembers him walking up the stairs as if nothing had happened, both legs bloody, and calmly asking her to call an ambulance.

Walter found others’ fragility unbearable. When his wife, Valérie’s mother, was diagnosed with cancer, Valérie sometimes kept him out of her room. “He would tell her, ‘You have to fight; you must eat; that’s how you get better.’ It was a form of psychological abuse.”

To Valérie, this trait in her father was a troubling echo of the Nazi emphasis on physical superiority. “A young German must be as swift as a greyhound, as tough as leather, and as hard as Krupp steel,” Hitler proclaimed in 1935. Lebensborn children born with conditions such as Down syndrome, cleft lip, or clubfoot were thrown out of the homes, or killed.

Sometimes Valérie worries about what she, and her son, might have inherited from her father. “When I see some of my son’s character traits—a little tough, a little authoritarian—which could belong to my father but also to me, I always have this fleeting anxiety: Did we pass along something of the Lebensborn?”

I

n the summer of 1945, Life magazine published a report, with pictures by the photographer Robert Capa, on the “super babies” of a Lebensborn home. “The Hohenhorst bastards of Himmler’s men are blue-eyed, flaxen-haired and pig fat,” one caption read. “Too much porridge, plenty of sunlight have made this Nazi baby in hand-knitted suit and bootees so fat and healthy that he completely fills his over-sized carriage,” read another. “Grown pig fat under care and overstuffing Nazi nurses, they now pose to the Allies a problem yet to be solved.” The tone gives an idea of the level of resentment that Americans and Europeans felt in 1945 toward those who were spared the war’s horrors—even toddlers.

But not all Lebensborn babies were blue-eyed, flaxen haired, or even, for that matter, “pig fat.” Likely because of the lack of bonding with a single caregiver, some children were developmentally delayed. Medical exams performed after the war indicate that Walter was underweight. A document from French social workers describes Gisèle as having had tantrums upon her arrival in France.

For Gisèle and her fellow Lebensborn children, the Allies’ liberation of Belgium marked the beginning of a journey—in wicker cradles wedged in the back of military trucks—through a devastated Europe. In The Factory of Perfect Children, the French journalist Boris Thiolay recounts that German soldiers in retreat left the Lebensborn home near Liège on September 1, 1944, with about 20 toddlers. After several stops in Germany and Poland, the children found themselves at the very first Lebensborn, in Steinhöring. Walter Beausert had ended up there too.

In Steinhöring, SS officials were crammed together with children and pregnant women from other institutions that were now closed. Boxes of documents cluttered the corridors of the maternity ward, where women continued to give birth.

When the news of Hitler’s death broke, officials burned as many documents as they could. Thiolay describes the goals of this purge: “The birth registers, the identity of the children, the fathers, the organization chart, the names of the people in charge: everything must disappear. The evidence of the Lebensborn’s very existence must be removed.” But the Nazis’ obsession with documents made fully expunging the records an impossible task—there were too many.

A few days after Hitler’s death, a small detachment of U.S. soldiers arrived in Steinhöring, and the children changed hands: The Americans were responsible for them now.

Later in 1945, Gisèle and Walter were transferred to Kloster Indersdorf, nine miles from Dachau, where they were housed in a 12th-century monastery that had been requisitioned by the U.S. Army for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to use as a reception center for displaced children. There, the Lebensborn children lived together with survivors: Jewish children who had made it out of the concentration camps, as well as Eastern and Central European gentile teenagers who had been forced laborers during the war.

Lillian Robbins, the American social worker who directed the displaced-children’s center at Kloster Indersdorf, consults with a nun in 1946. Walter Beausert is visible at far left; Gisèle is sitting up at Robbins’s feet. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of Lilo Plaschkes)

The older children were encouraged to help the younger ones. A picture shows three small blond girls gently combing babies’ hair and spoon-feeding them as if they were playing with dolls. Another photo shows a group of babies on a checkered comforter under the watch of the American social worker Lillian Robbins and a Sister of Mercy. In the corner, sitting on the floor away from the other toddlers, is little Walter, one eye closed, smiling at the photographer.

The UNRRA staff tried to find the children’s surviving family members, if there were any, though some children had no recorded identity. Some were given an approximate birth date. This was perhaps what happened with Walter Beausert, whose official date of birth falls on a suspicious, though of course possible, date: January 1, 1944. His birthplace was unknown, but, likely because he was believed to have previously lived at a Lebensborn home in France, UNRRA staff decided to send him there from Indersdorf.

As for young Gisela, her file showed that she was born in “Wégimont” (omitting the château’s full name), which staff believed to be a French town. She joined Walter in the convoy bound for the Meuse region of France, whose population had never recovered from World War I. Gisela became Gisèle, and her life as a French child began.

W

ere they “survivors,” these toddlers who owed their existence to Nazi birth policy, who ate fresh fruit and porridge while other babies were gassed or starved to death?

On October 10, 1947, in Nuremberg, four Lebensborn leaders appeared before a special American military tribunal as part of the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, which prosecuted ancillary Nazi leaders. Three charges were brought against them: crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in a criminal organization. Three out of the four leaders were found guilty of the third charge. But the tribunal established that the Lebensborn had been only a “welfare institution.” The children, therefore, were not considered victims.

Until the 1970s, Lebensborn homes were treated as a rumor, or described as stud farms where SS men mated with racially selected women. The first book to be published about Lebensborn came out in France in 1975 and contributed to this misunderstanding by suggesting that the “nurses” were in fact selected to be breeding mothers. Georg Lilienthal wrote the first academic work on the program, in 1986.

In the nine years the program lasted, at least 9,200 children were born in the homes. Some 1,200 were born in Norway, which had the most SS maternity homes outside Germany. After the war, these children, along with women who were suspected of having had affairs with German soldiers, were ostracized. Some of these women were even interned in camps. France had only one Lebensborn home, which operated for less than a year, so Lebensborn children there were far less likely to be recognized as such.

In 2011, Gisèle and Walter traveled to Indersdorf to join the annual commemoration held there by former residents of UNRRA’s reception center; Gisèle described the organizers as “Jewish children,” just as she still refers to herself as a “child of the Lebensborn.” “It was extraordinary” to be included in the ceremony, she told me. While she was in Indersdorf, she went to visit Dachau twice. She felt she needed to confront what she might have believed in had she been raised in an SS family.

Together, Gisèle and Walter started the Association for the Memory of Child Victims of the Lebensborn in 2016, an effort to encourage public recognition of Lebensborn children as victims of war.

Walter, for his part, became obsessed with gaining acceptance from the Jewish community. He studied the Torah and identified as a Zionist. “He used to celebrate Jewish holidays,” Valérie remembers. “His Jewish friends were a great help to my father. To tell him, ‘You are also a victim, Walter’ was the greatest gift.”

He died in 2021, wearing a Star of David around his neck. He had been in poor health, and living in a retirement home. A few days earlier, for the first time in his life, he had admitted that maybe Rita was not his mother.

Valérie has kept a comb that still contains her father’s hair. One day, she hopes to find out what secrets his DNA might contain.

G

isèle’s husband, Justin, died 15 years ago, but she still spends nearly every winter in Africa, in his village, where she is “famous,” she said, in part because residents saw her on TV, in a segment about the Lebensborn.

At home in Nancy, she keeps a photograph of her biological mother on display, though she doesn’t look at it much anymore. “It’s my heritage. I don’t want to forget that I was born from this woman,” she told me. All she wants now is for her story to be told. “I’m modest,” she joked. “I want the whole world to know about it.”

Her son Gabriel married a German woman, and her grandchildren speak German, a language she has completely forgotten. “It shows that history goes on,” she said. Her son Matthieu is working on a book about the Lebensborn, and with his wife, Camille, he wrote a play about the children’s story. Recently, I attended a reading at a small theater in Paris. I watched Gisèle, seated next to her daughter Virginie, as she watched her own story acted out.

“They say history is written by the victors,” one actor said. “But most of all, it’s written by the adults.” Gisèle discreetly dried her tears behind her glasses.

Social scientists have long expressed concerns that a large number of Americans embrace authoritarian modes of thinking that are centered on suppression of dissent, violence, and an infatuation with strong leaders. New evidence reveals that these authoritarian values are endorsed by a disturbing number of Americans, with the trend being most acute on the American More

The post The Cult of Violence: New Poll Finds Evidence of Authoritarian Values Driving U.S. Public Opinion appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

Marjorie Taylor Greene has called for a “national divorce,” voter suppression, and now seemingly civil war, appeals made all the more concerning by the key committee positions she holds in Congress.

In an interview Tuesday night with Fox News’s Sean Hannity, the Georgia representative lamented the fact that the country was so polarized and her “way of life” was under attack from the left.

“The last thing I ever want to see in America is a civil war,” she said. “But it’s going that direction, and we have to do something about it.”

In the same segment, Hannity also said he couldn’t see another option aside from splitting up the country, touting supposed benefits including continued fossil fuel use, paper-only ballots, and full state control of public education.

Greene’s outrageous comments came just hours after she told Charlie Kirk that Democratic voters who move to Republican-controlled states should lose the right to vote for five years. The day before that, she tweeted that the U.S. “[needs] a national divorce.”

Her borderline seditious rhetoric is made all the more frightening by the fact that Greene sits on several powerful committees in the House of Representatives, including the Oversight and Homeland Security committees. She earned those appointments through a shrewd rebrand, during which she allied herself closely with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, but her true colors seem to be coming back out. McCarthy has yet to speak publicly on Greene’s comments.

Despite her complaints about divisive “abuse” from the left, Greene has shared conspiracy theories, peddled racist and antisemitic beliefs, and helped incite the January 6 riot. And when she talks about “our way of life” being under attack, it’s a pretty safe bet she doesn’t mean a way of life that includes equal rights for all.

Educational polarization matters, but racial resentment matters more.

Just over 90 years ago, as it is so often rather euphemistically perceived, “Hitler came to power”, on 30th of January 1933. Well, Hitler did not simply “come” to power. Nor was there, as it is also called, a “Machtergreifung” – the taking of power. In fact, between 1932-1933, Hitler’s popularity had started to weaken. More

The post Hitler@90.de appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

American voters often waver from one election to the next between electing majorities of Republicans or Democrats to Congress or their state legislatures, yet the results of ballot initiatives remain remarkably predictable. Last November’s outcomes results again showed a majority of voters — even those in deep-red states — favoring progressive policies when voting on individual issues rather than voicing their party identity.

But instead of accepting those outcomes as guidance to better represent their constituents, many Republican legislatures are trying to obstruct or neuter citizen lawmaking.

Last year, pro-abortion-rights voters won in all six states with questions on the ballot, including the GOP strongholds of Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana. That success has advocates exploring ballot measures to amend state constitutions in a dozen or more states.

In other initiatives, voters abolished involuntary servitude as a punishment (Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont) and raised minimum wages (Nebraska, Nevada, and the District of Columbia). South Dakota became the seventh state (and the sixth under GOP control) to expand Medicaid via citizen initiative. And Michigan voters embedded reproductive rights and voter protection principles in the state constitution.

Two Republican officials on Michigan’s Board of State Canvassers initially blocked both of those initiatives from the ballot. Though supporters gathered a record 735,000 petition signatures for the reproductive-rights measure, the two officials claimed that inadequate spacing in the fine print of ballot petitions was disqualifying and voted to disqualify the voting rights initiative on another technicality. The initiatives’ backers filed lawsuits, and thankfully the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in both cases to prevent the sabotage and enable citizens to vote on the issues.

Twenty-four states enable proactive initiatives while two additional states enable citizens to nullify laws, but not enact new ones. Around the turn of the century, progressive initiatives began outnumbering conservative ones, and 2022 yielded victories on a wide range of progressive causes. But Republican politicians increasingly deem this an unacceptable intrusion into their powers and push bills to undermine ballot initiatives on three different fronts: erecting barriers to initiatives reaching the ballot, making passage more difficult and corrupting voters’ intent post-passage.

Last year, Ballotpedia counted a record 232 state bills impacting ballot measure processes, of which 23 passed. The Ballot Initiative Strategy Center (BISC), a nonprofit advocate for citizen lawmaking, listed 140 of those bills as impeding citizen initiatives. And the attacks are unrelenting: Missouri Republicans introduced a dozen such bills this January alone.

Ohio Republicans, meanwhile, proposed legislation to radically increase signature-gathering costs and require a 60 percent supermajority vote for constitutional initiatives. The author of the latter bill openly declared his intent: to block a forthcoming citizen initiative expanding reproductive choice. Also motivating the attack is an initiative to create an independent redistricting commission, which would neutralize gerrymanders that effectively ensure a Republican majority in the legislature. (In an unusual plot twist, a leading advocate for the initiative is Maureen O’Connor, a Republican and former Ohio Supreme Court chief justice.)

Roadblocks to citizen lawmaking may be making their intended impacts, as just 30 initiatives made state ballots in 2022 — the fewest this century. In Utah, for example, an out-of-state group with anonymous funding called the Foundation for Government Accountability helped pass a 2021 law banning paying signature gatherers per valid signature, which is currently standard practice. By nixing a key incentive for workers to gather more signatures than they would if paid only an hourly wage, the law will hike both the cost and duration of campaigns to qualify a ballot measure. “Qualification challenges, courts blocking measures and onerous restrictions” all contributed to the decrease, says Chris Figueredo, executive director of BISC.

Image via Ballotopedia.

Unlike direct voter-disenfranchisement tactics, the escalating assaults on direct democracy have generated few headlines. But regardless of our policy preferences, ballot initiatives provide a vital safety valve, giving citizens a tool to bypass unresponsive legislatures that ignore or defy their constituents. This corrective power is especially vital today, as gerrymandering makes dislodging officeholders in safe seats nearly impossible.

Despite the preponderance of progressive ballot victories, direct democracy is a nonpartisan, pro-democracy tool popular with citizens across the political spectrum. Two-thirds of the 24 states with proactive citizen initiatives typically have had trifecta Republican control of state government. In Colorado, which flipped from GOP control of all branches of government in 2004 to a Democratic trifecta today, 65 percent of voters supported a 2022 initiative to cut state income taxes. If more state legislatures flip to Democrats, conservative initiatives undoubtedly will serve as a check on their power as well.

The election results of 2022 demonstrated that citizen initiatives unite voters with differing party loyalties to advance common interests, often addressing issues where legislators decline to act. The threats to citizen lawmaking should be resisted in favor of protecting one key avenue to ensure frustrated voters a constructive way to engage and progress toward inclusive democracy.

Jeff Milchen is the founder and a board member of Reclaim Democracy!, which works to strengthen grassroots democracy and revoke excessive corporate power. Twitter: @JMilchen

©2025 RUPTURE.CAPITAL