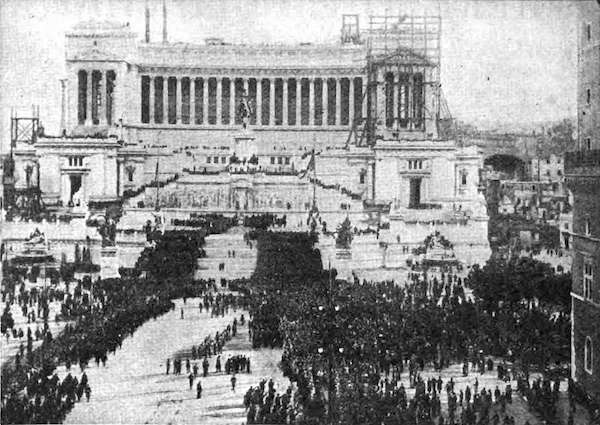

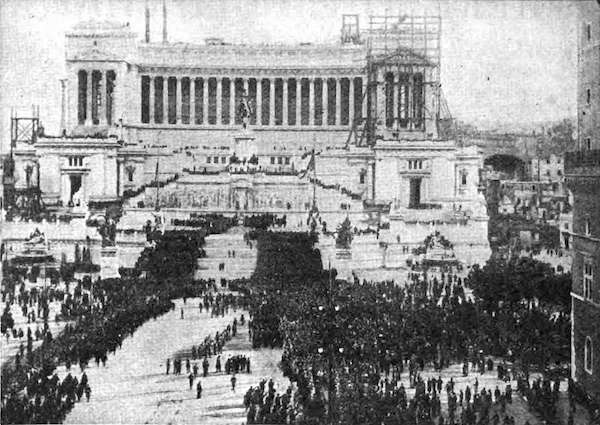

One hundred years ago, in October 1922, Benito Mussolini’s paramilitary blackshirts marched on the Italian capital to demand the dissolution of the government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta.

One hundred years ago, in October 1922, Benito Mussolini’s paramilitary blackshirts marched on the Italian capital to demand the dissolution of the government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta.

Author Tony Greenstein talks about his new book “Zionism during the Holocaust.”

The president speaks against election deniers running for office, saying they are leading a path to ‘chaos in America’

Donald Trump’s lawyers tailored their petition specifically to supreme court justice Clarence Thomas for reasons both practical and symbolic, Politico reports.

Thomas is well known for his conservative jurisprudence, but Politico notes he is also the justice responsible for handling emergency filings out of Georgia – which means he would get the Trump legal team’s petition about its election conduct, Politico says.

It starts with a tweet: It’s time for Christians in every country to come to…

Democratic candidate Richard Ringer, who is running for a statehouse seat in the 51st District of Pennsylvania, reported to the police that he was knocked unconscious and left bloodied by an attacker in his backyard.

Ringer is a 69-year-old man running against Republican Charity Graham Krupa for the seat.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reports ““He was larger than I am and he pinned me down on my left side. … He hit me 10 to 12 times in the head, in the face and by the eye and he knocked me out.”

Ringer believes the attack is due to political violence and threats against his person. Already there has been two cases of vandalism that have happened in the last couple of weeks

One, a threatening apparently election-related message spray-painted on his garage door and the other a brick thrown through a storm door window. The spray-painted message was partially washed off by the rain by the time Mr. Ringer saw it, but what was left clearly visible were the words “your race” and “dead.”

A pattern is emerging.

A pattern of violence is emerging against Democratic politicians and their families.

We will be documenting all of them.

The quicker film, TV, social media, the Internet, and advertising reflect the nobler Selma heroic masculinity, the sooner young men can aspire to emulate it.

Seven years ago my “Putin vs. Obama: ‘Macho Man’ vs. ‘Girly Boy’?” appeared on this site. But much has occurred in the “macho” world since then. Trump and Trumpism, with all of their macho attributes, for one thing; Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine for another. Plus, just a little over a month ago an enlightening book appeared that shines some light on our subject: Richard Reeves’s Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters and What to Do About It.

The recent January 6 hearings and trials involving leaders of two key groups supporting Trump that day—the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers—reminds us that the toxic macho Trumpist world continues to threaten our democracy.

In a January 20, 2021 essay on this site, I cited two articles, one entitled “Macho Politics Defined Trump’s Presidency, Culminating With Capitol Riot” and the other, “The ‘Pussy’ Presidency.” They indicated that Trump’s machoness, “rejects values typically associated with the feminine—compassion, collaboration, deference to expertise—as evidence of weakness”; that men, as well as women, who approve of dominating men were “likely to support Trump”; and that many of the symbols of the Capitol building occupiers (most of them white males) were “grotesquely masculine”–“the pelts, the horns, the capes, the exposed chests, the tactical gear.”

In Adam Hochschild’s review of Andy Campbell’s recent book, We Are Proud Boys, he notes that the group “provided much of the organizational backbone for the Jan. 6 insurrection.” The reviewer also writes of the group’s anxieties and that they seem to reflect a fear that masculinity is being lost. He also notes that Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes has said repeatedly that women’s place is in the home. And he quotes author Campbell’s words that misogyny is “baked into the rules” of the Proud Boys.

The Oath Keepers also reflect some elements of machismo. Stewart Rhodes, the group’s founder and a central figure in an October 2022 trial for seditious conspiracy (centered on the January 6 insurrection), served almost three years as an army paratrooper before breaking his back in a parachuting accident. Originally, when he founded his group in 2009, it concentrated on recruiting “military, first responders and police officers.” One source on the Oath Keepers emphasized the “macho, hierarchical and authoritarian mindset in the services that is perhaps more susceptible to far-right ideology.”

Such a mindset among some in the military was not new. In his 1977 book Rumor of War, Philip Caputo recalled how as a young college student in 1960 he enrolled in a Marine officer training program partly as a result of the romantic heroism of such war movies as Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), Guadalcanal Diary (1943), and Retreat, Hell! (1952) He explained his motivation as such:

“The heroic experience I sought was war; war, the ultimate adventure; war, the ordinary man’s most convenient means of escaping from the ordinary. . . . Already I saw myself charging up some distant beachhead like John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima, and then coming home a suntanned warrior with medals on my chest . . . I needed to prove something—my courage, my toughness, my manhood.”

As with John Wayne movies in the 1940s and 1950s, Rambo films later depicted a similar macho toughness.

As I indicated a decade ago in “Nationalism, Heroism, and ‘Manliness’ in the Russian Films of Alexei Balabanov,” such machismo could also be found in the films of director Balabanov, who died in 2013. In movies that appeared both before and after Putin came to power, he depicted heroes who were tough, courageous, and willing to kill, but who lacked more pacific virtues like compassion, empathy, and tolerance. More recently, the Russian film Granit(2021), among others, displayed some of the same macho glorification of violence and war as did Balabanov’s movies.

A recent Ukrainian article, “How Russian Cinema Dehumanized Ukrainians and Laid the Ground for Today’s War Crimes,” indicates that in declaring war on 24 February against Ukraine, Putin paraphrased a famous line from Balabanov’s Brother 2 (2000): “Where is strength, brother? Strength is in truth.”

And, of course, Putin seems very much in the mold of a Balabanov macho hero. As I noted seven years ago, the Russian leader liked to flaunt his “masculinity” in various poses, shirtless and muscles bulging, swimming, hunting, fishing, horseback riding. Or in various sports attire–for judo, hockey, skiing, diving. Or in a race car, speed boat, and fighter jet, or on a motorcycle. Or standing next to a bear and tiger (both tranquilized).

It would be simplistic to blame the Russian invasion of Ukraine on Putin’s misguided machismo, but it certainly is a factor. And as we witness Russian missile and drone attacks killing Ukrainian civilians, it’s obvious that he lacks some of the virtues like compassion and empathy that should counterbalance being tough, determined, and single-minded.

Macho presidents like Trump and Putin emerge out of cultures that support their efforts to become leaders of their countries. Films (and TV like Trump’s popular The Apprentice) are part of that culture. So too, especially in the U. S., is advertising.

A recent PBS NewsHour segment examined the advertising of guns. Duke psychologist Sarah Gaither, an expert on male aggression, told the PBS interviewer (Paul Solman) that a certain firearms ad sent “a very clear, unambiguous statement that if you are feeling insecure about your manhood, struggling with issues of fragile masculinity, the easiest way for you to reissue that masculinity is to buy their gun. Very simple.”

She added, “When we think about what it means to be a man, it’s very fixed, right? You have to be aggressive. You have to be tough. You have to protect your family. And the messages that gun ads in particular are showing are specifically targeting men who are struggling with this notion of what it means to be a man in our society.”

A former firearms executive confirmed Gaither’s analysis by saying that “advertising is all about encouraging this odd faux machismo, masculinity, own the room with guns. And it’s really, really dangerous.” He also said that during the last decade and a half men aged between about 18 and 35 have “been a near exclusive focus for the firearms industry.”

The prevalence of macho gun advertising is not the only sign that machoness continues in 2022 to be a strong cultural force. In June of this year The Washington Post magazine ran a story entitled “How 2022 Became the Year of Over-the-Top Masculinity in Politics.” It declared, “In races nationwide, ‘he-man’ politics is on the rise.”

The January 6, 2021 insurrection, the 2022 Russian aggression against Ukraine, the senseless gun violence in the U.S., and this year’s “he-man” U.S. politics all make Reeves’s book Of Boys and Men timely indeed. He cites numerous statistics to make his point that men, especially the least educated and in the USA, are suffering and need a positive image of masculinity. Just a few quick facts he provides:

Reeves thinks that the masculinity problem requires less emphasis on individual solutions and more on structural changes. For example, because of differences in maturation between boys and girls, he suggests that boys be a year older than girls when starting school.

Yet, whatever different answers might be suggested, there seems little doubt that cultures, whether in the U.S. or abroad, need to offer men more positive, more appealing images of masculinity than those of Trump, Putin, and Rambo. (Such positive male images could also help dissuade more women from finding macho men appealing.)

In a 2015 article by David Masciotra he contrasted two opposing views of masculinity as presented in the films American Sniper and Selma. In the first film, we see “the prevailing and prevalent projection of American manhood [which] is at once a cartoon, simplistic in its emphasis on strength and eschewal of sensitivity, and dangerous in its celebratory zeal for violence. It is not masculine as much as macho.”

The second, about Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil-rights protesters displays a truer and nobler type of masculinity. It is not one of war and killing, but protesting injustices, as was done at Selma, which requires a different type of heroism and courage, one more grounded in sound values and ethical judgments.

The quicker more films, TV programs, social media, the Internet, and even advertising, reflect the nobler type of Selma heroic masculinity, the sooner young men can aspire to emulate it. But pushback against such a transition is strong, especially among Trumpsters. A battle is not only being waged over U.S. democracy, but also over what it means to be a “real man.”

This article was originally published on History News Network.

In the end, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva won his runoff against

Jair Bolsonaro for the presidency of Brazil, becoming the first Brazilian

politician to be democratically elected president three times, whilst

condemning Bolsonaro to become the first sitting Brazilian president to be

denied a second term (Brazil’s longest serving head of state, Getúlio Vargas,

was only elected twice, though he also ruled Brazil as a dictator between 1930

and 1934, and between 1937 and 1945). It was, to be sure, a near-run thing. For after defying pollsters’ predictions and the expectations of many both in Brazil and

internationally that Lula would get the 51 percent of the vote needed to be

elected in the first round, Bolsonaro then gained ground in the last week

before the runoff, holding Lula to 48.2 percent of the vote while rebounding

to secure 43.2 percent for himself, a gap of about 6.1 million votes.

Bolsonaro’s surprisingly strong showing was chastening, not to

say terrifying—not just to the left both in Brazil and abroad, but also to the

Brazilian center and center right that had come to oppose Bolsonaro and dread

what he might do were he to win a second term, so much so that the former

four-time governor of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin of the center-right Social

Democracy Party, who had been defeated by Lula in the 2006 election,

was willing to sign on this time as Lula’s vice presidential running mate.

Nevertheless, it was widely assumed that Lula would gain votes

in the second round thanks to the support that he received almost

immediately after the first round from two longtime rivals: the third-place

finisher, Simone Tebet of the centrist Democratic Movement Party, the MDB, who

had gotten 4.16 percent of the vote, and the fourth-place finisher, Ciro Gomes

of the center-left Democratic Labor Party, the PDT, a onetime minister in

Lula’s government, who had received 3 percent. Their backing, observers

believed, would lead many of the 8.1 million Brazilians who had voted

for them to support Lula the second time around. It was also assumed that of

the 38 million voters who had abstained or spoiled their ballots in the first

round, more who participated in round two would

vote for Lula than for Bolsonaro.

Instead, it was Bolsonaro who grew stronger, and Lula won 50.9

percent to 49.1 percent, and by only two million votes—that is to say, with

less than half the number that had separated him from Bolsonaro in the first

round. This is not to downplay Lula’s personal victory, for his truly phoenix-like return from what seemed like political death and personal

disgrace. Having been president between 2003 and 2010, and then having remained

the dominant figure in his Workers’ Party, the PT, during the presidency of his

chosen successor and former chief of staff, Dilma Rousseff, before her

constitutionally highly dubious impeachment and removal from office by the

Brazilian Congress in 2017, Lula was himself given a nine-and-a-half-year

prison sentence for corruption. He served almost two years before being freed

provisionally by Brazil’s Supreme Court in 2019, and his conviction was

nullified in 2021.

On the Brazilian left, what happened to Dilma is all but

universally viewed as a slow motion right-wing coup. This may be overstating

things in the sense that one can also view Dilma’s ouster as a power play pure

and simple by her vice president, Michel Temer, to take her

place, as he indeed did. Nevertheless, the destitution of Dilma and the jailing

of Lula, who had planned to run for the presidency in 2018 but was barred from

doing so, opened the way for Bolsonaro’s victory in the presidential elections

that year. But today, it is Lula who has vanquished his enemies. The sole

bitter note is that Sergio Moro, Bolsonaro’s former minister of justice and the man

who, as a prosecutor, secured Lula’s conviction and was, in a sense, his Jean

Valjean, just won election to the Brazilian Senate.

Unsurprisingly, the Latin American left is

ecstatic. Argentina’s Alberto Fernández wrote on his Twitter feed: “Congratulations Lula!

Your victory opens up a new era in the history of Latin America … a time of

hope that starts right now.” Even before Lula had been declared the

winner, Gustavo Petro, the former guerrilla and a committed leftist who won the

presidency of Colombia last June, was

tweeting “Viva Lula,” while his vice president, Francia Márquez, tweeted that Colombia and

Brazil under Lula’s leadership would combine to “restore peace dignity and

peace to Our America [a catchphrase of the contemporary Latin American left].”

For his part, Cuba’s dictator Miguel Díaz-Canel wrote, “Cuba congratulates you,

dear comrade … Lula returns, the Labor Party of Brazil returns, social justice will

return.” He promised Lula that his

government could “always count on Cuba.” And not to be outdone, the president

of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, declared that with the return of Lula

to office, there would be “equality and humanism” in Brazil.

They are entitled to their moment of relieved excitement. But

the idea that Lula’s victory is ideologically akin to that of Petro’s or that,

as Ricardo Monreal, the majority leader of the Mexican Senate, put it excitedly in a tweet,

Lula will “direct his country [back] towards the left,” is entirely

far-fetched. For in reality, there are very few signs that we will see a return

of leftist dominance to Brazilian politics. During the campaign, Lula

emphasized over and over again that his government would not just be a

government of the PT.

And for him to succeed, Lula will have to make sure this really

will be the case. Lula’s own popularity—that is, the establishment,

coalition-building Lula of today, not the left-wing firebrand he once was and

the Latin American left hopes he still is—is quite high across a wide swathe of

Brazilian opinion. But outside of its strongholds in the states of the poor

northeast of Brazil, the PT is extremely unpopular, even among many who voted

for Lula. They may view his prosecution by Sergio Moro as persecution and his

imprisonment as a rank injustice purely motivated by the Bolsonarist right’s

desire to extinguish his political career, but they also firmly believe that

the PT itself was extremely corrupt under Lula and Dilma and remains so today.

However important his victory is, Lula is scarcely coming into

office with a resounding mandate from the Brazilian people, nor can one

legitimately speak of Bolsonarism being defeated even if Bolsonaro himself

lost. The right scored massive gains in the ideologically

fragmented Brazilian Congress, with Bolsonaro’s right-wing Liberal Party now the largest bloc

with 99 seats. Lula will simply not be able to get legislation passed without

the support of at least a part of the Brazilian right. In the Senate, where a

third of the seats were in play, Bolsonaro’s bloc is also the largest party.

And in the gubernatorial races, Bolsonaro-supported candidates won in 14 of

Brazil’s 27 states, while center-right (but not necessarily Bolsonarist)

candidates won in four others, including in Lula’s home state of Pernambuco,

leaving the center and center left with only nine governorships.

A Bolsonaro supporter even won the governor’s race in the

critical swing state of Minas Gerais, even though it voted for Lula for

president. In short, the right won the Congress and the governorships, while

Lula, not the left, won the presidency. In

the words of Benjamin Fogel, a brilliant analyst of Brazilian politics whose bona fides are

unimpeachable both as a fierce opponent of Bolsonaro and as a supporter of Lula

(they are not the same thing by any means), “Nobody else but [Lula], the

greatest Brazilian political mind of all time could have beaten Bolsonaro in

this election, and even then, it is too close for comfort.” And, he added,

“That’s truly terrifying.”

Lula’s challenges in office will be daunting. He

will be hemmed

in on all sides: a business establishment that will demand balanced budgets while

the popular movements of the left and the unions that are his base (gig economy

workers in Brazil tend toward Bolsonaro) will expect enormous increases in

social spending. And while there is a good deal a Brazilian president can do

unilaterally, and Lula can certainly reverse Bolsonaro’s determination to

shrink the role of the state, budgets must be passed by Congress. The one piece

of really good news, not just for Brazil but for the planet, is that restoring

protections to the Amazon is something that can largely be done by decree, and

these are moves Lula will unquestionably make.

And the conditions in Brazil Lula will preside over are very

different from those that obtained when he left office in 2010. For one thing,

the commodity boom that allowed him to pay for massive increases in social

spending may not be over, but it has very different characteristics in an era

of high inflation, low growth, and of course all the knock-on

effects of the war in Ukraine. And Brazil has been changed forever by the rise of the

evangelicals who are Bolsonaro’s and Bolsonarism’s most ardent and loyal

supporters. There were approximately 20 million evangelicals when Lula first

took office in 2003. By the time Dilma was impeached, they were said to number

about 60 million. Today, only five years later, there are between

65 and 70 million evangelicals in Brazil, a little under a third of its total population.

To say they will be restive under Lula’s government would be to

wildly understate the case. It is also worth noting that while recent elections

in Latin America indeed have brought the left to power in the continent’s five

most important economies (though to claim that Boric in Chile and Petro in

Colombia, let alone Maduro in Venezuela, belong to the same political family would

be absurd), this has not only been the result of an ideological shift. As the

Brazilian political scientist Oliver Stuenkel has pointed out, “Brazil’s

presidential elections mark the 15th straight opposition

victory in Latin America. Over the past [few] years, not a single democratic

leader has managed to get reelected or pick his or her successor.” And, he notes, “Brazil is angrier, more

divided, and the geopolitical context far worse” than it was the last time Lula

held office.

Brazilians celebrating Lula’s election in the streets of

São Paulo can hardly be blamed for doing so. A second Bolsonaro term really did

pose a threat to Brazilian democracy, which was why many on the center right

supported Lula. But once the euphoria is passed, one fears they will find that

in the coming years in Brazil, there will not be very much cause for

celebration.

Adolf Hitler holds a reception for leading figures in German business, including Dr Gustav Krupp (foreground), 1939. (Ullstein Bild via Getty Images)

In 2019, the German tabloid Bild published shocking revelations about one of the country’s most powerful companies. Bild discovered that Albert Reimann — creator of a family business whose investment firm, JAB Holding, has majority stakes in brands from Dr Pepper to Jacobs Douwe Egberts — was a devoted Nazi who sexually abused, tortured, and humiliated slave workers in his business during World War II. The Reimann family fortune is estimated at €33 billion. The family decided to confront its dark past and donated millions of euros to nonprofit organizations devoted to helping religious and national minorities and seeking out the families of the war prisoners forced to work for the grandfather’s firm.

This was just one recent case showing how Nazi tycoons had been able to cover up their dark pasts in postwar West Germany. One of the journalists who dug into the archives to find out about this history was David de Jong. His new book, Nazi Billionaires, follows the story of men who became part of the Third Reich’s business and financial elite, making their fortunes by stealing Jewish-owned firms, banks, and other assets, as well as exploiting forced and slave labor in concentration camps during World War II. Companies like Siemens, Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler-Benz, Dr. Oetker, Porsche, Krupp, IG Farben, and many more cooperated with the SS, which built “satellite concentration camps” near these private companies’ factories and mines where slave laborers toiled in the most appalling conditions. While, after 1945, legal proceedings were launched against Nazi businessmen, almost none would be punished. Industrialists like Günther Quandt, Friedrich Flick, and Ferdinand Porsche were even allowed to keep their assets and continue business as usual. During the “economic miracle” of the 1950s in Germany, they made even bigger fortunes, and their family businesses remain among the most powerful in Germany. Some have even continued to support far-right political parties.

But how did the relationship between Adolf Hitler and the business and financial elite develop during the interwar period? And why were Nazi businessmen set free after the war, even though their activities were key to the regime’s operations? Jacobin’s Ondřej Bělíček spoke to De Jong about the fate of the Nazi billionaires.

Your book starts with the moment when Hermann Göring and Adolf Hitler invited industrialists for a meeting and asked them to donate huge sums to the Nazi Party. Sometimes it is said that Hitler used these businessmen for his own purposes, but in another sense, he was the figure that they were looking for. How would you describe the relationship between Germany’s financial and industrial elite and the Nazi Party?

I would agree that in a way most of the men that I write about were sheer opportunists. These families were already very rich before Hitler seized power in 1933, with the exception of the Porsche-Piëch family, which laid the foundations for their wealth during the Third Reich. They were leading business families during the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich, in West Germany, and still today in unified Germany. These businessmen looked to maximize profit, and they thrived in any political system. I would even argue that they would have somehow risen to the top even in a communist system. Their main goal was to maximize profit and expand their business empires and fortunes regardless of the political system.

These men became interested in Hitler and the Nazi Party once it had his first electoral success in Germany in September 1930. It was the period when the Great Depression hit Germany with a wave of discontent and unemployment. The entire business world hung in the balance, and that, for the first time, opened the door for Hitler to Germany’s business community, which had before mostly supported establishment conservative figures. It opened the door for them to have conversations, but they didn’t really start supporting Hitler until he came to power on January 30, 1933. In that meeting that you refer to, he promised them something that he initially delivered on, which is economic and political stability and the rearmament of Germany, which they greatly profited from. They made billions of reichsmarks that were flowing to them from their steel, machinery, and car companies that were retooled to produce weapons and war material.

Hitler gave them the means to make more money and control anything they wanted in exchange for their loyalty.

He promised to make them more money, but also to protect their interests, because it was a very unstable period. Sure, it was about making more money, but that was always their bottom line. But now it was also really about reviving their companies, getting Germany’s economy back to where it was before World War I and Weimar.

In your book, you follow the story of a few main protagonists among the Third Reich’s financiers, industrialists, and weapons manufacturers, who exploited Nazi race policies and made huge fortunes. Could you describe the main practices that these people used to get what they wanted and make themselves the wealthiest and most powerful people in Nazi Germany?

There were three ways to profit from the Nazi system. I already mentioned weapons production, which was not criminal, although it was forbidden under the Treaty of Versailles. But from 1935 onward, with the introduction of the Nuremberg race laws, you see the sliding scale that devolves into criminality with the disfranchisement and expropriation of Jewish business owners and families.

Initially, it had this veneer of legality, where they coerced Jewish entrepreneurs to sign over their companies, for far below market value, to the men I write about. Or else these families wanted to sell their companies because they wanted to flee Nazi Germany. But then, as the 1930s go on, you see that it devolves into outright theft and robbery and seizure of Jewish-owned assets. They used the same practice in German-occupied territory across Europe, with business owners who were robbed just because the Germans had occupied their country. And the third way was the mass exploitation of forced and slave labor. After the German invasion into the Soviet Union in 1941, the mass deportation of forced and slave laborers from all across Europe to German factories and mines began. An estimated 12 to 20 million people were deported to work in Germany, and approximately 2.5 million people died due to the horrific working conditions in factories, mines, and labor camps.

The most shocking part of this story is the exploitation of the prisoners from concentration camps as a slave workforce for the private companies. To what extent did these private companies use slave labor — and what were the working conditions?

There were three ways German companies procured this labor. There were forced laborers who were mainly from Eastern Europe, who were deported by the millions through the German labor front, and paid much less than German laborers and kept in labor camps. Then there were prisoners of war. They were not paid. Thirdly, you had concentration camp labor. That was a collaboration of the SS with big companies like BMW, Daimler, Volkswagen, IG Farben, Siemens, Krupp, Dr. Oetker, and companies controlled by Günther Quandt and Friedrich Flick. These people were slaves, and the aim was to exterminate them through labor. These companies leased prisoners from the SS for four reichsmark per day for unskilled labor and six reichsmark per day for skilled labor. The SS built sub-concentration camps, or “satellite concentration camps,” as they were called, on factory complexes. These camps were guarded by the SS, and there was barely any medical attention and food for the captives. Prisoners were executed, hanged, or shot for the most minor infringements, and they were abused at their workplaces. They didn’t have any protective clothing, so they handled the machinery with their bare hands. There were the most awful working conditions you can imagine.

After the war, trials against the Nazi financial and industrial elite were prepared, and it seemed like justice would be done. But soon it turned out that almost none of the main culprits were sentenced to jail. Could you describe how the trials were initially set up and what determined the outcome of these trials?

It’s important to distinguish between two things. First, there were the Nuremberg trials. The first and main Nuremberg trial was a major success, and it was focused on the top political and military protagonists of the Nazi regime. And there was the plan to hold trials against industrialists, which would be similar to the first main trial. But the Americans were worried that the Soviets would turn it into an anti-capitalist show trial. At the same time, the British and the French were so economically weak that they didn’t want to put money into another massive tribunal. The Americans decided to go at it alone and staged eleven trials at Nuremberg.

Three of these trials were held against industrialists. They concerned Friedrich Flick and his managers, Alfred Krupp and his managers, and the entire executive board of IG Farben. Those trials were very well prepared, and justice was done. However, the American judges didn’t really get most of the dense evidentiary material, translated from German. The Americans limited the number of trials against industrialists because they didn’t want to put capitalism on trial. At that time, the Cold War was getting started, and the Americans made this policy decision where they wanted to rebuild West Germany as a democratically viable and economically strong state, which would act as a buffer against the Soviet Union and the encroachment of communism.

Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Germans went free for their crimes.

I understand that policy decision, but where it went completely wrong, in my opinion, was when the Americans, British, and French handed over hundreds of thousands of suspected Nazi war criminals back to West German authorities for so-called denazification processes, which were very flawed legal trials that went on in western Germany between 1945 and 1950. It basically meant that hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Germans went free for their crimes, because there was no interest on the German side to judge people on crimes that they themselves had committed and sympathies that they had held as well.

The denazification of Germany is a myth. It never took place. There was a continuation of money and power from Nazi Germany to West Germany, and also, to an extent, in East Germany, because former SS officers became high-ranking Stasi and party officials. But it was far more pervasive in West Germany, where — in whatever part of society, whether business, legal, medical, academic, or media — there was no denazification.

It’s shocking that the top leaders of Nazi Germany’s financial elite were allowed to continue doing business as usual.

Yes, totally. They were allowed to keep all their assets. Except, of course, apart from their assets located in Soviet-occupied East Germany, where the authorities expropriated them and took everything. But in West Germany, they were allowed to keep everything.

As for the trials, I found it odd that investigators weren’t interested in the brutal practices of the industrialists like exploitation of forced slave labor and running subcamps near their factories. Why do you think that was the case?

It was related to the fact that they didn’t want to put capitalism on trial. Similarly, that’s why they were allowed to keep all their assets, because business had to thrive in West Germany if they wanted it to be an effective buffer against the Soviet Union, and if Western Europe was to be revived again. I think the Americans were worried that, if they investigated the labor practices, it could turn against them, and they could be asked questions like, “OK, but what are you doing in your factories?” or “What about the exploitation of African Americans in your country?” That’s something they wanted to avoid at all costs.

It’s often said that Germany confronted its dark past. The student movement of the 1960s is frequently cited as the moment when German society started to ask difficult questions. After reading your book, I’m not so sure if German society was that successful in this respect. You mention that the first major backlash against the family of one of the most powerful industrialists in the Third Reich, Friedrich Flick, happened in the mid-1990s. And only in recent years does there seem to be a wider debate about history of other major Nazis who built their empires during the Third Reich and continued to do so after the war. Why do you think this is happening now and not much earlier, for instance when the Cold War ended?

It’s because German business has never been forced to take any kind of moral responsibility for its crimes during the Third Reich. Sure, there were financial compensations, but they always negotiated that they didn’t have to admit any culpability or guilt for the crimes they committed. They paid money, but paying money is something different than actually coming out and taking responsibility for the actions in the past. The lack of responsibility has allowed these business families to sweep the history under the rug up to this day.

German business has never been forced to take any kind of moral responsibility for its crimes during the Third Reich.

So when we talk about how Germany managed to confront its past, do you think it’s a myth?

If you look at a macro level then yes, they’ve reckoned with it pretty well. If you look on a micro level, nobody wants to talk about it. Nobody really wants to talk about what their grandparents did during World War II. This debate in the 1960s was more of a generational conflict. People who were born after the war became very critical toward power structures that were still in place. Very violent movements were formed from that debate, like the Rote Armee Fraktion, but they were mainly challenging the conservatism and the lack of historical reckoning that Germany had, which didn’t much occur in the business world, which was still a very conservative world. That reckoning really didn’t come until the 1990s or the 2000s. And in my opinion, it’s still far from being fulfilled.

How did German society react to the findings that recently appeared in the newspapers about the dark Nazi past of certain billionaire companies?

The problem in Germany is that the public has become a little bit desensitized to revelations regarding its Nazi past. You notice that people are inundated with such revelations on a daily basis. They have become used to them, and they aren’t shocked.

Some of the families of former Nazi businessmen took public responsibility for the past following pressure from media and the public. In your book, you particularly mentioned the damage control by the Reimann family business as an example of how to deal with findings about a firm’s dark past. Why do you think the steps they took are the best way to deal with it?

Because they’re transparent about the fact that their father and grandfather were committed Nazis. Also, they’ve renamed their foundation after their other grandfather, who turned out to be murdered in the Holocaust. My point is that there should be more of this historical transparency and taking responsibility for the past. But if you name your foundations after Herbert Quandt or Friedrich Flick or Ferdinand Porsche, who were committed Nazis or voluntary SS officers who committed war crimes on a large scale, than you can’t celebrate their business successes while leaving out their Nazi history.

What reaction did you get from the public on your book?

There have been two major developments since the book came out. First, the BMW foundation Herbert Quandt was inundated with angry letters from people who received money from that foundation but felt lied to because they had been given money in the name of a Nazi war criminal. So the foundation came out with a statement and promised change, but BMW is stuck between conservative shareholder Stefan Quandt, who honors his father, and angry foundation members, who are not very powerful but were very public about their anger. Second, Porsche is now negotiating with the heirs of Adolf Rosenberger, the company’s cofounder, who was pushed out of Porsche in 1935 and erased from Porsche company history for being Jewish. So they want to restore his place in Porsche company history. It’s also due to the fact that they have so many financial interests on the line right now, with the company going to the stock exchange and being valued at €80 billion, which is a massive amount.

RUPTURE.CAPITAL IN 2025