Archive for category: #Fascism #Elections #Caesarism

The Democratic Party leadership, along with the Liz Cheney wing of the Republican Party, seems intent on provoking a war with both Russia and China at the same time, all supposedly out of love for democracy and opposition to tyranny. The sidewalks of cities across the US are increasingly filled with the stench of the dead, who have passed away inside the tents in which they spent their last days. And you can still hear liberals wondering aloud why anyone would possibly vote for Trump again. More

The post The Progressive Industrial Complex and Our Fascist Future appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

Nearly everything Americans hear about the U.S.-Mexico border is wrong, and it’s very likely because of one relatively small but extremely well-funded and influential group of American racists.

On July 5, 2022, a group of officials in Texas held a curious press conference. It consisted of a handful of politicians from across the state praying and insisting, using openly white supremacist rhetoric about immigrant “hordes” and “invasions”, making terrifying claims, without a shred of evidence, that the United States was living through a disastrous attack on its very integrity at the hands of refugees and asylum seekers attempting to cross into the country.

Misleading statements about the security of the border have been escalating for years. What was remarkable was the brazenness of the extremist, nativist framing that the Texas politicians were pushing, and the fact that their rhetoric had absolutely no relationship with reality. “We’re under attack like Pearl Harbor!” Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick told Fox News, as though bombs were raining down on him at that very moment.

This line of false and nakedly racist rhetoric, comparing immigrants and refugees to attackers and diseases, is no accident. One could argue that it was the very reason for the press conference’s existence in the first place. The increasingly blatant bigotry in immigration discourse is the culmination of decades of targeted influence by an assortment of largely unknown groups known as the Tanton network.

The Tanton network is, as its name suggests, a criss-crossing mesh of politicians, lobbyists, think tanks, non-governmental organizations, pundits legitimized by op-eds in major newspapers, and billionaire money.

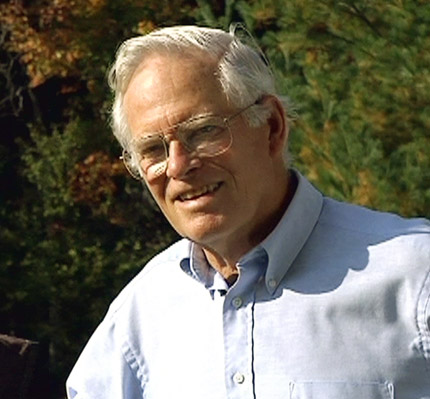

John Tanton. Photo source: Tanton Estate.

John Tanton. Photo source: Tanton Estate.This network is named after its creator, John Tanton, a retired Michigan ophthalmologist and birdwatcher by the time he discovered the spectre of overpopulation, courtesy of entomologist Paul R. Ehrlich’s book “The Population Bomb“, which ushered in decades of policies of coercive sterilization and worse, worldwide. The spectre is kept alive by a network of disinformation purveyors whose only goal is to, in its founder’s own words, maintain a ruling white majority in the United States.

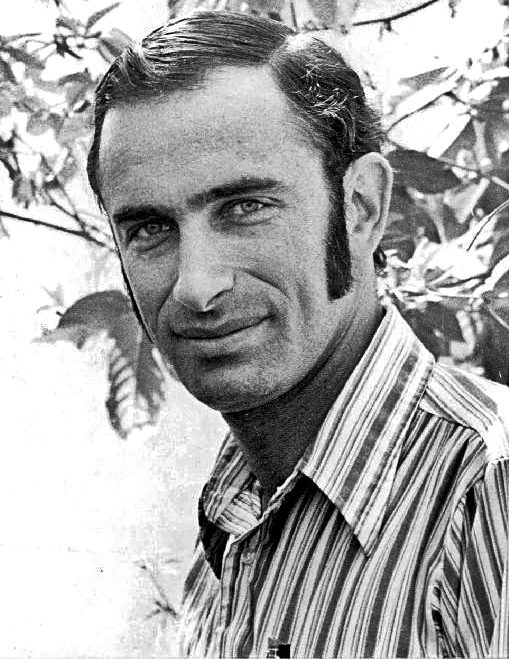

Paul R. Ehrlich, author of “The Population Bomb”. 1974 photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul R. Ehrlich, author of “The Population Bomb”. 1974 photo via Wikimedia Commons.Ehrlich went on to sit on the advisory board of Tanton’s flagship organization, the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), for many years; he was also a founder of another Tanton-linked group, Zero Population Growth. “We must have population control at home, hopefully through a system of incentives and penalties, but by compulsion if voluntary methods fail,” Ehrlich wrote. But he didn’t stop there. “We must use our political power,” he also wrote, “to push other countries into… population control.”

Tanton’s obsession was initially with overpopulation as a whole – he felt that there needed to simply be fewer people on the planet. He preached for efforts such as contraception and abortion (he and his wife Mary Lou were frequent donors to groups like Planned Parenthood and the Sierra Club) in order to bring progressives around to what he perceived as an overwhelming need for population control.

As so often happens, however, Tanton quickly decided that only some populations might need controlling — those he personally found the most questionable. He quickly changed tactics to settle on immigration restriction after realizing that eugenics might not be palatable to most Americans in the decades following the revelations about Nazi atrocities during World War II. Tanton ultimately decided that “population control” should be inflicted more on certain people than others, and advocated for a “Euro-American majority, and a clear one at that.” And thus was the eugenics movement reborn, couched as “immigration restriction.”

Tanton reportedly loved to sit at his typewriter and tap out long letters to various groups asking for funding. In fact, much of Tanton’s available correspondence appears to be a nearly inexhaustible supply of fundraising letters to as many groups as he could.

Wealthy Backers for Tanton’s Cause

John Tanton’s letters often detailed a plan that he came to call “passive eugenics,” which consists of ideas such as coerced sterilization, restricting childbearing ages, and anti-immigrant disinformation campaigns. He even published an essay in 1975 called “The Case for Passive Eugenics.” In this way, Tanton apparently discovered that he shared many ideals with the richest people in the country— his first and primary funder, Cordelia Scaife May, believed that immigration should be sharply limited in the United States.

May, whom Tanton affectionately called “Cordy” in letters, began life with progressive leanings, but ended up detesting most humans, particularly immigrants and people of color, and she had the inherited wealth to go a good long way toward bringing about her particular vision for the world. She wrote to a cousin in the 1980s in language that by now is likely familiar to all Americans:

“When we hear of immigrants, we instinctively think of Mexicans because they are the most numerous and given the greatest press coverage. In truth, we are being invaded on all fronts. Filipinos are pouring into Hawaii. Almost anyone from the Caribbean countries and Eastern South America who can make it to the Virgin Islands or Puerto Rico can eventually make it to the U.S. mainland. Orientals and Indians come across the long stretches of unmanned border we share with Canada.

“When the Mariel boat people arrived in Florida from Cuba, much was made of the possibly deleterious impact they might have on American life… criminal habits, radical political thought, exotic diseases, neighborhood disruption, etc., …but no reporter, columnist, nor commentator cited their most dangerous contribution of all: a birth rate far higher than that of our native population. They breed like hamsters.”

– Cordelia Scaife May

May and her foundation effectively financed Tanton’s efforts and inroads for years. The warm, lucrative relationship between Tanton and “Cordy” continued until her apparent suicide in 2005. By 2013, May’s Pittsburgh-based Colcom Foundation was the single biggest bankroller of the anti-immigration movement. (May also contributed funds to white nationalist group VDARE and paid to republish Jean Raspail’s work of deeply racist fanfiction, “The Camp of the Saints”, which former Trump adviser Steve Bannon calls his favorite book.)

But the family connections didn’t end with Cordelia May. Her brother, Richard Mellon Scaife, a major early funder and board trustee of The Heritage Foundation, gave his blessing to Tanton’s efforts through the Colcom Foundation.

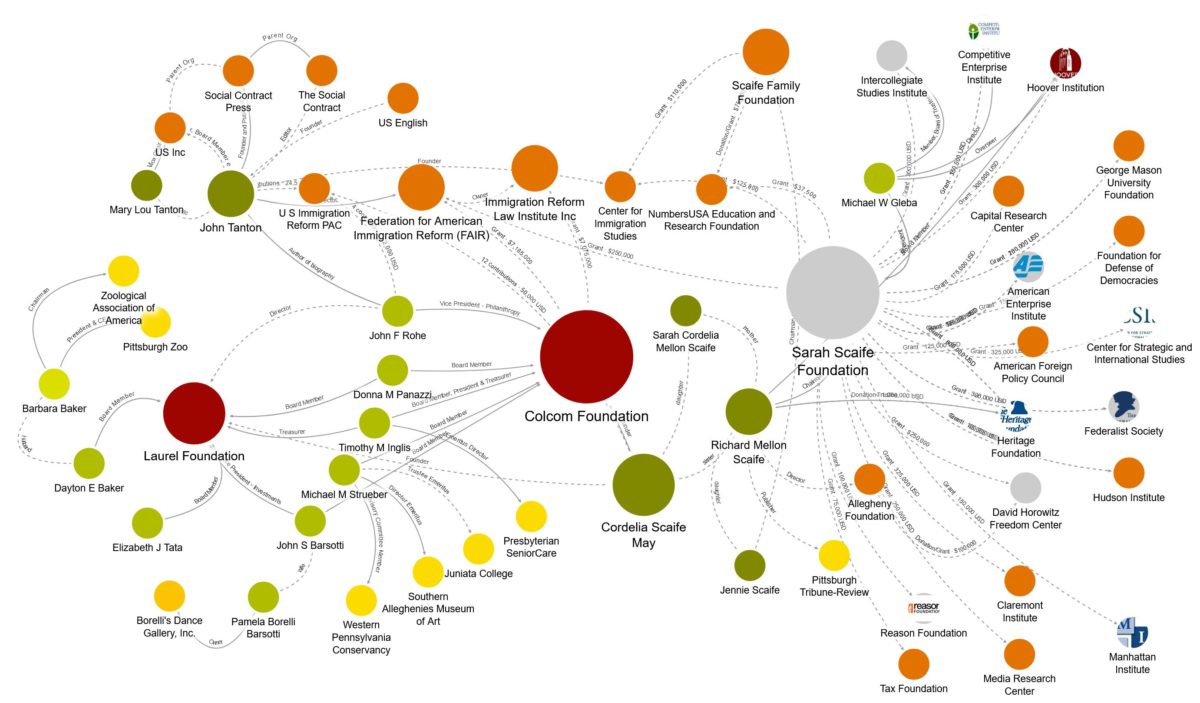

Map of interlocking relationships including the Colcom Foundation, Sarah Scaife Foundation, and Tanton Network entities like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). Note: some entities shown here do not support Tanton-style agendas, but share some funding and personnel links. Source: sousmarin on Littlesis.org.

Map of interlocking relationships including the Colcom Foundation, Sarah Scaife Foundation, and Tanton Network entities like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). Note: some entities shown here do not support Tanton-style agendas, but share some funding and personnel links. Source: sousmarin on Littlesis.org.

Colcom’s vice president of philanthropy, John Rohe, wrote a glowing biography about the Tantons called “Mary Lou and John Tanton: A Journey into American Conservation.” (Rohe also wrote something called “A Bicentennial Malthusian Essay: Conservation, Population and the Indifference to Limits.”)

Their efforts paid massive dividends. In 1986, American immigration law was changed for the far more draconian, even as it offered asylum to millions already within the United States, with IRCA, the Immigration Reform and Control Act.

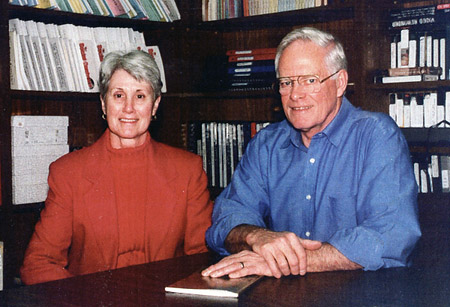

Mary Lou and John Tanton. Photo source: Tanton Estate.

Mary Lou and John Tanton. Photo source: Tanton Estate.By the 1990s, misleading “overpopulation” narratives were accepted by the American public at large, with national magazines blaring terrifying narratives about all the evils that overpopulation could bring, playing directly into national debates over immigration and overcrowding. These were the results of extensive efforts by the Tanton network, as Tanton himself makes clear in an “oral history” with Dan Stein (who still heads FAIR) in 1994.

“I agree with you that special interests are misunderstood. One reason special interest groups go up is because the system is so complicated that you have to, as Pat Noonan says ‘Focus, Focus, Focus,’ if you hope to get anything done. I used to tell people that FAIR’s role in the 1986 Immigration Act cost us eight years and eight million dollars for whatever it was we were able to accomplish in that particular act.“

– John Tanton

The duo also detail their working relationship with then-Senator Alan K. Simpson (R-Wyoming), listed as the bill’s author, and how they were able to leverage that into greater visibility:

“Well, the organization was not well-known at that point in time. It was well-known enough to be known to the editors of The New York Times, and there were some letters to the editor there. It was well-known enough to have retained a high- powered lobbying firm , and it was well-known enough, thanks in part to Senator Simpson’s alliance with FAIR early on, to secure occasional appearances on MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour and a couple here and there, maybe the Today Show.“

– Dan Stein

Unicorn Riot’s #Icebreaker series includes leaked ICE & INS operations manuals that show how federal immigration agents enforce the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA).

U.S.-Mexico border fence near San Diego & Tijuana. Photo by Brooke Binkowski.

U.S.-Mexico border fence near San Diego & Tijuana. Photo by Brooke Binkowski.Tanton Network Advances in the Trump Era

By 2015, when Donald Trump first announced that he planned to run for U.S. President, these groups were well known throughout the political and media ecosystem. Indeed, its relative obscurity was due to the fact that until Trump’s openly nativist campaign, news organizations by and large had begun to understand that the network of nonprofits and lobbying groups was not representing its true aims.

“The anti-immigrant movement’s talking points and tactics during the current immigration debate are remarkably similar to the ones used during the last major push for immigration reform in 2007,” reads one representative article published by the Anti-Defamation League in 2013. “Reestablishing and buttressing front groups is an example of the movement’s repeat tactics.”

But by 2016, the ‘Overton window’ of acceptable discourse was sliding rapidly to the far right, thanks to concerted efforts from the Tanton network’s disinformation purveyors and their “objective” enablers in the popular media. Soon, the Federation for American Immigration Reform, the Center for Immigration Studies, and other affiliated groups and organizations that had once been recognized as serving up nothing more than white supremacist fare, such as The Social Contract Press, were regularly quoted in news stories, tapped by pundits, invited onto televised panels, all without revealing their true affiliations and goals, such as seeding white supremacist conspiracy theories such as “the Great Replacement” into the mainstream.

This nearly immediate acquiescence to disinformation purveyors by the national press paved the way for Tanton network operatives to be brought into the federal government en masse by the Trump administration. A 2016 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette story shows many links between the Trump campaign and Scaife money. Many of those named in the report are likely familiar to Americans, such as former transportation secretary Elaine Chao, former education secretary Betsy Devos, billionaires Peter Thiel and Rebekah Mercer, and more.

By 2017, many of those same Tanton affiliates were either embedded in or directly influencing Trump’s Department of Homeland Security, enacting their agenda mainly against immigrant women and children. Key figures included USCIS Ombudsman Julie Kirchner, fresh off a years-long stint at the Federation for American Immigration Reform, Ken Cuccinelli in the Department of Homeland Security, whose legal stunts included a 2008 attempt to overturn birthright citizenship, and Kris Kobach, a pet lawyer for the Federation for American Immigration Reform’s legal wing, the Immigration Reform Law Institute, or IRLI.

Photo by Brooke Binkowski.

Photo by Brooke Binkowski.

It was under their watch that family separations and coerced or forced sterilizations took place en masse in the United States following the stated goals and aims of the Tanton network.

But now, although Trump and his administration are out of power, there has been no real pushback or consequence for these acts which are clearly classified as acts of genocide under the Geneva Convention. Instead, Joe Biden’s administration, constrained by Trump appointed judges, hostile Republicans, and political “norms,” has continued much of Trump’s policies at the border.

In the absence of legal or social consequences for any of these acts or the rhetoric that inevitably accompanies and justifies such acts, the Tanton network has once again upped its game as catastrophic climate change looms, giving authoritarian leaders the excuses they need to shut down international points of entry. They no longer seem to feel constrained to wrap their nativism in pseudoscience and dogwhistles, but instead push warlike language of “hordes” and “invasion” in what appears to be an effort to spark stochastic violence — acts of terror whose likelihood can be statistically but not individually predicted, encouraged by signaling aggression against specific groups of people.

But while the Tanton network is skilled at nuisance lawsuits, weaponized rhetoric, and fundraising, they are also a relatively small group of people who are highly vulnerable to counter messaging and losing their positions of power. Their narratives are closed loops that can be derailed with transparency and fact-based reporting.

Photo by Brooke Binkowski.

Photo by Brooke Binkowski.Private Papers Sought in Michigan

Hassan Ahmad, a Virginia based immigration lawyer, has spearheaded an ongoing transparency effort around John Tanton’s private papers, which he donated to the University of Michigan with the caveat that some not be unsealed until 2035. Ahmad and supporters argue that these papers contain a wealth of knowledge about Tanton’s plans and contacts that, in light of the Trump presidency and all its corrosive effects on American immigration, are squarely in the public interest.

As of 2022, the case over Tanton’s papers has been dragging on for five years. Many of its twists and turns make little sense, Ahmad said, noting that at least three of the now-sealed boxes had once been open to the public. “They could have stopped a long time ago if they wanted to,” he said. “If Tanton had really wanted to keep these papers secret, there were other ways to do it. He didn’t do it.” The University of Michigan is arguing that opening the sealed boxes of papers would constitute an invasion of privacy.

The boxes of paperwork would bring new life to journalists and researchers working to shed light on John Tanton’s destructive legacy. Over time, link decay, changes in editorial direction, and paywalls have increasingly interfered with efforts to track down background information on the Tanton network and its allies, at the same time that transparency and equality have become crucial in the age of hybrid attacks and catastrophic climate change, particularly around the future of migration and immigration. As the Tanton network’s influence and funding continues to grow, so do the calls to uncover the truth about the history, and the future, of the United States’ immigration policies.

Brooke Binkowski is a longtime breaking news and border reporter turned debunker and managing editor for TruthOrFiction.com. You can find her on Twitter at @brooklynmarie.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

For more border & immigration coverage see our stories on ‘No More Deaths’, and sanctuary movements:

Unicorn Riot’s No More Deaths Coverage:

- Crisis: Borderlands – March 14, 2017

- Humanitarian Aid Camp Raided By US Border Patrol – June 15, 2017

- Humanitarian Arrested After Group Releases Report Implicating US Border Patrol – January 23, 2018

- Migrant Aid Workers Targeted by Border Agencies in Retaliation, Documents Suggest – March 22, 2019

Unicorn Riot’s Coverage of the Sanctuary Movement and Immigration:

- GEO Group’s ICE Jail Lies to Immigration Lawyer, Attempts Unlawful Deportation (July 2, 2020)

- Racial Justice Teach-in at Abolish ICE Camp in Aurora CO (June 13, 2020)

- Another Immigrant Claims Sanctuary from Deportation in Colorado (Feb. 14, 2020)

- Immigrant Rights Advocates Rally in Response to Rotten Food Given to Detainees (Jan. 6, 2020)

- Ingrid Encalada Latorre Pardoned After 2+ Years Claiming Sanctuary (Dec. 28, 2019)

- The Price to Oversee ICE: 200+ Protesters March in Aurora Suburb Home to GEO Group ICE Warden (Sep. 30, 2019)

- Twin Cities Jewish Community Blockades ICE Building, 27 Cited (Aug. 2, 2019)

- Passions Run High at ‘Close the Concentration Camps’ Protest (July 22, 2019)

- Hundreds in CO Plan Rally to ‘Close the Concentration Camps’ (July 12, 2019)

- Thousands March in Minneapolis to Stop Separating Families (June 30, 2019)

- Jeanette Vizguerra’s U-Visa Denied While in Sanctuary Second Time (June 27, 2019)

- CO Community Gathers Outside GEO ICE Facility on Longest Day of Year (June 21, 2019)

- Occupy ICE Denver Camps Outside GEO ICE Detention Center (Oct. 29, 2018)

- #OccupyICE Movement Grows Momentum in Colorado (Aug. 6, 2018)

- ICE Occupation Emerges at Denver Field Office (July 30, 2018)

- Philadelphia Reduces Police Help To ICE; ‘Occupy ICE’ Camp Moves (July 30, 2018)

- Protesters Occupy Philadelphia ICE Office (July 2, 2018)

- Protests Target ICE Contractor General Dynamics (June 29, 2018)

- Ninth Annual CO Love Knows No Borders, No Walls Vigil (Feb. 5, 2018)

- November Vigil at GEO Group ICE Detention Center in CO (Nov. 6, 2017)

- Ingrid Encalada Latorre Returns to Sanctuary; Four Claim Sanctuary in CO (Oct. 27, 2017)

- Ingrid Encalada Latorre Leaves Sanctuary After Six Months; Granted Temporary Stay (May 27, 2017)

- Indonesian Undocumented Immigrant Detained at ICE Check-In (May 24, 2017)

- Jeanette Vizguerra, Among Others, Celebrate Victories Against ICE Deportation Attempts (May 17, 2017)

- Sanctuary Movement Leader, Arturo Hernandez Garcia, Detained by ICE While at Work (April 30, 2017)

- Jeanette Vizguerra Named One of Time’s 100 Most Influential People as She Remains in Sanctuary (April 22, 2017)

- Crisis: Borderlands (March 14, 2017)

- Arizona Anti-ICE Demo Meets Arrests and Chemical Agents (Feb. 17, 2017)

- Deportations Begin Under Trump’s Regime (Feb. 14, 2017)

- Love Knows No BAN No Walls Vigil at GEO ICE Detention Center (Feb. 8, 2017)

The post Eugenics, Border Wars & Population Control: The Tanton Network appeared first on UNICORN RIOT.

Originally published at The Dissenter, a Shadowproof newsletter

In 2019, longtime national security journalist William Arkin appeared on “Democracy Now!” and spoke out against liberals in the United States who believed the FBI (and CIA) could save the country from President Donald Trump.

“The FBI, in particular, has a deplorable record in American society, from Martin Luther King and the peace movements of the 1960s all the way up through Wen Ho Lee and others who have been persecuted by the FBI,” Arkin stated. “And there’s no real evidence that the FBI is that competent of an institution to begin with in terms of even pursuing the prosecutions that it’s pursuing.”

“But yet we lionize them. We hold them up on a pedestal, that somehow they are the truth-tellers, that they’re the ones who are getting to the bottom of things, when there’s just no evidence that that’s the case,” Arkin added.

Arkin has a proven record of speaking out against perpetual war and challenging the immense power of the national security state. He co-authored the 2011 book, Top Secret America: The Rise of the American Security State and also wrote the book American Coup, which he describes as documenting the “creeping fascism of homeland security.”

When Arkin appeared on “Democracy Now!”, he had just left NBC News and circulated a letter that criticized the media organization for “emulating” the national security state in the era of Trump.

I’d argue that under Trump, the national security establishment not only hasn’t missed a beat but indeed has gained dangerous strength. Now it is ever more autonomous and practically impervious to criticism. I’d also argue, ever so gingerly, that NBC has become somewhat lost in its own verve, proxies of boring moderation and conventional wisdom, defender of the government against Trump, cheerleader for open and subtle threat mongering, in love with procedure and protocol over all else (including results). I accept that there’s a lot to report here, but I’m more worried about how much we are missing. Hence my desire to take a step back and think why so little changes with regard to America’s wars.

I recount all of the above to show you why I setup an interview with Arkin about the Justice Department and FBI’s handling of the investigation into Trump and his possession of documents at Mar-a-Lago. He has the credibility to offer important insights into what pursuing an Espionage Act prosecution against a former US president may mean for the United States.

Arkin is currently the senior editor for intelligence at Newsweek. He has written multiple reports related to the Justice Department’s investigation into former President Donald Trump’s mishandling of classified information. His reporting revealed that the FBI had an informant, who had knowledge of what documents Trump had in his possession and where they were located. He later reported more details on Trump’s “private stash” of documents.

In the 30-minute interview, which was recorded on August 19, Arkin outlines the timeline of events, what the DOJ investigation may mean for Trump’s potential 2024 presidential campaign, and why he believes the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago has sparked one of the biggest political disasters in the history of the bureau.

*Below is a transcript of the interview with minor edits to improve clarity.

WILLIAM ARKIN: It’s important to just talk about the background of what happened at Mar-a-Lago because this has been going on since Trump left office. So even though most people were not aware, there’s been a battle between the Trump camp and the National Archives since January 2021 about this whole question of what records the Trump administration had taken with them from the White House.

If you talk to Trump people, they’ll tell you, oh, we had such a rushed departure—and of course the reason is because Donald Trump did not accept the terms of the election—that we by mistake took boxes to Mar-a-Lago. Indeed, in January of this year the Trump camp delivered 15 boxes of presidential records to the National Archives, and it was in the course of that delivery that I think the National Archives came to see that these were not complete sets of records, that there were a lot of presidential records which were still being held by the Trump camp, and they requested additional records.

And basically this has been going on now since January 2022 this year and that culminated by a grand jury subpoena, which was delivered to the Trump camp in the end of May, and that subpoena basically said here are specific documents and types of documents that we would like you to return and the next step essentially was that three FBI agents and a Justice Department official visited Mar-a-Lago on June 3, and they retrieved some documents. But they also in the process of that inspected the storage room at Mar-a-Lago, where Trump was keeping his presidential materials and recognized that there were additional materials with additional classified information.

Now the FBI knew that there were additional materials. They asked the Trump [camp] to put better locks on the door of the storage room. They knew that they were there. So when the search occurred on August 8, it was a surprise to most people. Maybe not so much to the people who had been following this back and forth. But it does raise the question as to whether or not what Merrick Garland, the attorney general says, is true, which is did they in fact exhaust all the possibilities for getting the additional documents.

Now we know that they took 27 boxes of documents from Mar-a-Lago last week. So that’s a total of 42 boxes of documents, and the 27 boxes of documents that they took under this search warrant included 11 sets of classified documents and an additional leather box that they had retrieved that contained top secret sensitive compartmented information.

Mar-a-Lago (Photo: Government Accountability Office)

Mar-a-Lago (Photo: Government Accountability Office)

I reported earlier last week that the FBI had a confidential human source inside the Trump camp that essentially let them on to the fact that Donald Trump was secreting additional documents away. And at this point based upon my reporting, it looks like the FBI had two targets in their raid on Mar-a-Lago. One was to retrieve the additional boxes that they knew were in the storage room, and two was to find this stash of documents that Donald Trump was evidently segregating from those 27 boxes, which the FBI concluded as part of their investigation that Donald Trump had no intention of returning.

I wouldn’t say that the search at Mar-a-Lago was a cover for the fact that they knew that Donald Trump had additional material, but Donald Trump himself has given us clues to the fact that there were two separate searches. Because we know that the storage room was entered. We know that they entered the bedroom in the presidential office. Donald Trump is the one who said that they broke into his personal safe. And in fact when the FBI returned Donald Trump’s passports earlier this week, it was evident that they had gotten them from somewhere that wasn’t the storage room. It pretty much confirmed what Donald Trump had claimed—that his personal safe had been broken into.

It’s kind of a game of chicken between the FBI and the Trump camp. Right, Donald Trump can’t say, oh, I was secreting away particular documents, and that’s what the FBI is really going after. He’s just going to go on this straight I’ve-been-politically-persecuted line, and that’s what he’s going to stick with. And of course once the Trump camp gets their act together and figures out what they’re actually going to say, the reality is they’re probably going to argue, why did [the FBI] execute the search warrant at all because we were cooperating with the National Archives? And if they had asked us for additional boxes, we would have returned them.

So, yes, it’s true that Trump has kind of argued they were my private papers. They weren’t belonging to the National Archives. But it’s sort of irrelevant because if you don’t consider what it was that the FBI really going after, you wouldn’t understand why they would have thought it necessary to execute this extraordinary and unprecedented of a personal residence of a former president, which has never been done in our history.

If you understand that the FBI obviously felt that Donald Trump was not planning to return everything, that they knew from their confidential human source and their investigation that it existed (and more or less where it existed), and that they were concerned that Donald Trump would weaponize that material. And that could be using it for monetary gain or using it as part of his election efforts. We don’t really know the answer there.

But if you consider all of those, then the search begins to make some sense, even though I think politically it’s been a disaster for the FBI, and as much as the mainstream might be rallying around the FBI and saying, oh, poor FBI, the truth of the matter is that it seems like this is another naive investigation on the part of the FBI and Justice Department that thinks that because we have all of the paperwork in order that it makes sense to execute this but I think in fact it’s probably strengthened Donald Trump’s hand within the Republican Party and also within the electorate, who feel like in fact after six years of investigations if they haven’t indicted him yet that it is persecution.

And there’s some validity to that. Let’s just imagine for a moment that Bernie Sanders was president, and that the FBI was going after him for six years. I mean people would be screaming bloody murder. Either indict him or stop it. And so I imagine in the coming weeks we are either going to see Donald Trump indicted finally for a peripheral question, which is possession of these documents. Not the content of the documents, but possession of them.

Or we’re going to see a political disaster in the making, which is that everyone is going to rally behind Donald Trump within the Republican camp and basically say this is an outrageous act on the part of the Biden administration, even though I believe that it didn’t have political overtones to it or undertones to it. That they inadvertently stepped into something like the Mueller investigation or like Comey talking about Hillary Clinton’s emails, where they just didn’t understand what the political fallout of their actions were going to be.

FBI Director Christopher Wray (Photo: Federal Bureau of Investigation)

FBI Director Christopher Wray (Photo: Federal Bureau of Investigation)

KEVIN GOSZTOLA: What is your assessment of the divisions or factions or the nature of the FBI or Justice Department—not necessarily just right now but in the FBI or Justice Department up to this moment—and their relationship to Donald Trump?

Because I think it’s so important for people to know the deeper context, and since you’ve done this reporting on administrations for so long, how extraordinary it was that they had such a different posture to the president than some of the more recent previous presidents in history. Because this relationship is completely unlike Obama. It’s completely unlike George W. Bush. It’s completely unlike what we have with Joe Biden. There’s no reason for antagonism to exist between those prior presidents.

ARKIN: Well, we’ve never had a Donald Trump before. That’s the most important ingredient here. The FBI has always been a political organization, though it would like to portray itself as not one. During the civil rights era or during the communist scare of the 1950s or doing the period of time where it was basically persecuting those who were against the war in Vietnam, etc, the FBI has always hewed in the direction of being a right-wing institution with an antagonism towards the left.

With Donald Trump, the shift began to be apparent that the FBI, in fact, had a lot of people within its ranks who were anti-Trump. In fact, the long bipartisan era of the FBI was over. We live in a topsy-turvy world where the Rachel Maddows of the world are cheering the FBI on and the right-wing hates them. That’s unprecedented in modern history, that the left somehow thinks that the CIA and FBI are going to protect us from Donald Trump rather than the right [supporting these agencies]. Even like the left is quasi-cheerleaders for perpetual war and for the continuation of the war in Syria and for the war in Ukraine, etc. Whereas the right is much more of a traditional American isolationist entity.

Look, Donald Trump isn’t smart enough to articulate and/or represent the actual currents, which exist within American society, but there are currents that exist within American society. It’s Washington DC, and the New York bubble and the LA bubble versus the rest of the country, or urban versus rural. Whatever way you want to describe it. Donald Trump was elected because of that divide. Because of that increasing divide between officialdom and the rest of the American population.

So the FBI, which has always been seen in the mainstream’s eyes as being a neutral party, became a very political party. They just did. They became a political party. And at the same time that Barack Obama was being criticized during the 2016 presidential election cycle for not doing about the accusations vis a vis Russian collusion and Russian intervention—Obama said, well, I’m not going to do more because I don’t want to put my finger on the scale of the election. It’s up to the American people to decide who is the next president.

But they wanted the FBI to put their finger on the scale, and that was what happened when Comey had a press conference right prior to the election and stated Hillary [Clinton] broke the law but we’re not going to indict her. That just pissed everybody off on both sides, but most importantly, what it did was introduce the idea that Hillary Clinton was a lawbreaker and hadn’t been held accountable whereas Donald Trump was being accused of being lawbreaker and people were assuming that he was guilty.

I’m sorry. I live in a country where I still believe innocent until proven guilty. Donald Trump is innocent. He’s innocent of claims of collusion. He’s innocent of claims of cooperation. He’s innocent of all these claims until he is proven guilty. So while we might be comfortable in the mainstream saying Donald Trump’s lies about the election—I mean, listen to NPR. They say it in that way, and it should be Donald Trump’s claims about the election. By saying the word lies, you are already declaring what your political position is. That’s not impartial journalism as I understand it to be.

So Donald Trump is innocent until proven guilty, and now this search warrant has been executed. I hope as a citizen that either the Justice Department brings charges against Donald Trump or it starts to reevaluate whether it continues to spend its resources and our money in going after this guy.

GOSZTOLA: Let me ask you a few specific questions. Do you actually believe that this is a mistake on Donald Trump’s part that he has these boxes? I seem to get from the way you are setting up the timeline that that seems like a very convenient excuse at this hour. Have you seen any evidence that they really made this mistake with this many boxes of documents?

ARKIN: I mean, Melania’s shoes might have taken 42 boxes themselves. We don’t know how many boxes were actually removed from the White House in that six-hour period on January 20. But I think it’s important that you think because Donald Trump screwed up and didn’t have a normal transition and boxes ended up going to Mar-a-Lago that shouldn’t have gone to Mar-a-Lago, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t Donald Trump’s fault. I mean, this is his trick, right? They were sent by mistake, but if it had been a normal transition, they wouldn’t have been sent by mistake.

You have to ultimately say that this falls on Donald Trump in terms of what direction was given to the White House staff and his subordinates in terms of preparing the White House for the Biden administration to come into the office. So, yes, I can see that the documents might have ended up in Mar-a-Lago by mistake, but the mistake is that Donald Trump didn’t accept the results of the election and didn’t facilitate an ordinary transition.

Why it’s so important then to see the decision-making on the part of the FBI and the Justice Department about this extraordinary search is that it obviously has to be about something bigger than just run-of-the-mill secrets. And I know that some people will think, well wait a minute? Top secret documents are documents that could cause exceptionally grave damage to the United States. But I’ve been in this business a long time, and I also am a former intelligence officer in the US military, and I can tell you there’s a heckuva lot of top secret documents that have no meaning outside of just the source of information that is just describing what we know.

A lot of this [information] is classified because of the possibility that its release would divulge intelligence sources and methods, and some of those intelligence sources and methods, such as our satellite capabilities, are well-known anyhow. But I understand that people have this idea that somehow Donald Trump stole secrets, when I’m kind of doubtful that there was really much material that was in there that was intentional or detrimental to US national security in a specific way.

However, we know that Donald Trump during his entire presidency took documents to his residence, asked for copies of documents, ripped pages out of documents that were delivered to him, squirreled away documents that were interesting to him, and those documents dealt with everything from Russiagate and the political travails of Donald Trump to nuclear capabilities of Iran and North Korea and possibly even Russia and China. So we know that it’s a wide variety of documents—things that Donald Trump found interesting. That’s basically this leather box or this separate stash of documents that were in his personal safe, and that was really the focus.

I think in the end people will be surprised that it’s not really an argument about the sensitivity of the documents per se. It’s just about the documents. It’s just about the documents. They don’t need to argue that the documents are highly classified or whatever. That’s terminology that we use in the news media. And it’s kind of bullshit.

If Donald Trump just had a bunch of personal letters that belonged to the National Archives under the Presidential Records Act, they would still be making the same arguments as to why we need to retrieve those letters from the Trump camp. So I think it was really only in the case of documents that they thought that Donald Trump had personally segregated—and might use in the future, that were the ones that they were concerned about.

Photo: Trump White House Archives

Photo: Trump White House Archives

GOSZTOLA: That’s the problem, right? We get this from your reporting. It does a good job of communicating this. It doesn’t seem like the FBI is moved to conduct the search just because Donald Trump has [these boxes]. Because we see the ongoing conversations with representatives over returning the boxes. But there’s something about the stash. There’s some kind of fear that they have that he’s going to do something with the documents that he has privately, and obviously, we’re at an important point in time.

There’s a Trump circus, but there’s also an election circus. We are dominated from 2023 to November 2024 will be primaries and general electon, wall-to-wall media. And you know this better than anyone having survived alongside it—how much elections dominate and overshadow important national security journalism and other stories that should be given attention rather than this horse race coverage.

It’s hard not to think based upon what you’ve been reporting that there is some motivation that, okay, we have a small window of time to do this before Donald Trump might start his campaign. And also these documents, as your sources told you, [Trump] is going to weaponize this information.

So I think it’s worth asking you what your assessment is of the Russiagate counter-investigation. That is the investigation into the people who were investigating Donald Trump and the abuses of power that they were alleged to have committed by people who were empowered, like Durham, to investigate these people and what was happening. There have been some things related to Carter Page, and there’s been some isolated examples. [The Trump camp has] tried to craft a narrative that people within these institutions were trying to, as they would put it, take down Donald Trump. That’s how they present it to the American people.

If the FBI is going in there to take this stash of documents, and it is proven out that there are documents related to the Russia investigation that Donald Trump was keeping because he thought they exonerated him or whatever, that seems pretty bad as far as the FBI and the idea that it’s supposed to be a neutral institution. I mean, obviously, historically it’s always acted politically. But if the FBI is going above and beyond to seem like it’s not a political organization, how do you green light a search when it is going to be so patently obvious later that you are taking this step?

ARKIN: Let’s talk about it in the context of 2024. First of all, we have to understand that what was been revealed as result of the 2016 election and Russiagate is that there was FBI wrongdoing. Whether you consider minor or not, the truth of the matter is that we’ve had FBI agents go to jail already for falsifying FISA applications, for using official email and text to campaign against Donald Trump as a candidate, and even people who were involved in the investigations who are supposed to be neutral parties essentially declaring that they are anti-Trump.

I don’t take from that that it’s big or little. I don’t want to quibble about whether or not the FBI is or isn’t pro- anti-Trump, but what we see is they make mistakes. Tons of them. This is not a perfect institution. We should stop seeing it as a perfect institution.

If you understand that this is a flawed institution, where the lawyers are saying, well, you can do this, you can do that, and you can do this and you can do that, and now the FBI has to decide are we publicly going to be able to do this, that the reality in the end is the FBI seems to operate on the idea that if the paperwork is immaculate that the political consequences are going to be neutral. That’s where the FBI has gotten it wrong over and over again. The paperwork can be immaculate, and yet they can be doing exactly wrong thing politically.

If I’m a smart Justice Department official, I’m going to say we got to let the chips fall where they may. If the raid on Mar-a-Lago helps Donald Trump, we still have to do what’s legally correct to do. Now you might ask, well, did they exhaust all the possibilities in talking to the Trump camp? Did they absolutely have to do this? What evidence did they have that Donald Trump was going to weaponize the information? Was there some imminent reason for them to have to do it now? Etc etc.

In the end, if I’m a Justice Department official appearing before the news media, I might answer every question that I understand that you are arguing the political consequences, but our job is to enforce the law. And Donald Trump was breaking the law, and we needed to enforce the law and it took us this long to get to the place where it was obvious that Donald Trump was not going to return the material that he had in his possession.

All of this is going to come out in the coming weeks or months, but whether or not it is going to benefit Donald Trump in this election cycle, and then specifically, in 2024, we’ll have to see. I’m fearful that the effect of this is going to be that more people will lose respect for the government. More people will see Washington as persecuting Donald Trump, and that the Biden administration and the Biden Justice Department are not going to be able to get off that merry-go-round and that’s going to add to the Trump camp’s constituency.

We already see that prominent Republicans from all walks of life except for two people on the planet (Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger) have all rallied behind Donald Trump on this issue. I would say that this is perhaps one of the largest crises in the FBI’s history. They may not understand it themselves. They may have made mistakes here in what they did, and they may have been legally justified to do what they did. But politically I believe it will be seen as a disaster.

GOSZTOLA: Finally I want to put to you the issue of the Espionage Act being part of the conversation. A lot of my work has been watching and monitoring and covering the developments in individual Espionage Act prosecutions over the last decade-plus. Those individuals and their attorneys would also say that they were charged for materials that would not cause exceptionally grave damage, and yet the book was thrown thrown at them and they had their lives ruined and their careers ended. So why shouldn’t the same be true for Donald Trump?

I think it presents a crisis. I think it’s part of this crisis of the liberals and the Democratic Party establishment really feeling strongly about pushing forward with whatever the Justice Department is about to do. What’s your sense of the risk if Donald Trump were to be charged with violating the Espionage Act?

You’re talking to people about the potential charges that could be brought. Is this even a distinct possibility? You said unlawful possession, which can be within that law. But there are other laws. Do you think it would be a more minor law to keep the Espionage Act out of the conversation?

ARKIN: We now know that the Espionage Act was only being referenced because of section 793(d) of the Espionage Act, which is an area of the Espionage Act that deals with if you are in possession of classified documents and the federal government asks you to return them, and you don’t return them, you’re in violation of 793(d) of the Espionage Act.

It’s called the Espionage Act, what it’s been called since 1917, but it also happens to be just one of a handful of laws that deal with security classification. The rest of the security classification system exists under executive order. That’s why Donald Trump and his people are arguing that he declassified everything. But it’s not altogether true. Some elements of classified information do fall under statute, such as atomic energy information or information about the identities of CIA sources, etc. Those fall under statute.

So it’s unfortunate that the Espionage Act is the place where this is contained, this provision about returning classified material in your possession, because it’s abused in a way because we don’t have modern legislation. Perhaps one of the solutions will be that we will finally have a law passed, which will specify what is classified and unclassified information and what is the modern security classification system and where are the authorities and what’s against the law and what’s not against the law.

That does influence Julian Assange’s problems in the courts. It influences other whistleblowers who have been charged with the Espionage Act, and even if they were not guilty of espionage, as we think of it, they are charged under the Espionage Act. So we need to clean this up because I don’t think that we have a law in a proper way that really specifies what the true state of play is here.

If I support Julian Assange, I want Donald Trump to spur along a better articulation of what is the actual purpose of the Espionage Act. To have say for instance Julian Assange, a foreign national charged under the Espionage Act—espionage against who? If he committed espionage against Australia, then he should be charged in his own country of his nationality.

In some ways, if I’m a supporter of Julian Assange, I want to see that Donald Trump helps to clarify what is this law and what it can really be used for. Because in the cases of [Chelsea] Manning, in the cases of Tom Drake, in the case of Julian Assange, I think it’s been misapplied. And in the case of journalism, there have been attempts at various times within our recent past going back to the Reagan administration, where the federal government has sought to use the Espionage Act as a way of suppressing a free press.

Again, if I’m really interested in the future, I would want to see Congress step in finally and establish an omnibus law that deals with security classification in this country. That’s more important than Donald Trump.

The post Interview With National Security Journalist William Arkin: FBI Faces Brewing Political Disaster After Mar-a-Lago Raid appeared first on Shadowproof.

Ahead of Tuesday’s primary election in Florida, Republican Governor Ron DeSantis’s new Office of Election Crimes and Security made its first arrests of people it alleged engaged in voter fraud in the 2020 election. Almost all those charged were people who were formerly incarcerated and mistakenly thought they were eligible to vote. People of all political affiliations “are now being dragged from their homes in handcuffs because all they ever wanted to do was participate in democracy,” says Desmond Meade, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, who spearheaded an initiative to reenfranchise people with prior felony convictions, before it was overturned by Republicans.

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

We turn now to Florida, where the newly formed Office of Election Crimes and Security has made its first arrests of people it accuses of committing voter fraud tied to the 2020 election. The arrests come just as voters are set to go to the polls Tuesday in the state’s primary. The office was a pet project of Republican Governor Ron DeSantis, who announced the arrests Thursday.

GOV. RON DESANTIS: The state of Florida has charged and is in the process of arresting 20 individuals across the state for voter fraud.

AMY GOODMAN: Many of those arrested were people who were formerly incarcerated. The state said they did not have their voting rights properly restored or were ineligible due to their convictions.

For more, we go to Orlando, Florida, to speak with Desmond Meade, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which works with returning citizens on restoring their voting rights. They’re helping some first-time voters hitting the polls for the primary. He’s also chairman of the Floridians for a Fair Democracy, spearheaded Amendment 4, which reenfranchised more than 1.4 million Floridians, but then Republican lawmakers overturned that. His latest book is titled Let My People Vote: My Battle to Restore the Civil Rights of Returning Citizens.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Desmond. If you could start off by explaining what is going on? Who were these people arrested? What message was being sent? And go back to when you really spearheaded this movement, that got overwhelmingly approved in Florida, that returning citizens, as you say, formerly incarcerated people, can be able to vote again.

DESMOND MEADE: Well, first of all, thank you so much for having me on again, Amy. It’s always a pleasure to speak with you.

You know, when I look at this situation, what I see more than anything is that we’re in dangerous times right now. And I do believe that we’re at a moment where we may have to just shift some of our dialogue — right? — and engage in a more holistic and a deeper conversation about what democracy really means to us. Right? What we’re seeing here with these individuals who were arrested was the state actually crossing a line, and a very important line, when you talk about democracy and when you talk about criminal justice reform.

These individuals arrested was, in some way or another, given assurances by the state that they were in fact able to vote, able to register to vote. The onus is on the state to determine whether or not an individual is eligible or not. And when these individuals actually reached out to the state — or, in some cases, the state reached out to them to encourage them to register to vote — once they did that and they was able to participate in an election, guess what: Now they’re getting arrested.

And it’s very disheartening. You know, we’re talking about, just like in Amendment 4, we led this effort to enfranchise people from all walks of life and all political persuasions. Right? We fought just as hard for the person who wanted to vote for Donald Trump as the one who wished they could have voted for President Barack Obama. In these arrests, we’re seeing Republicans, we’re seeing Democrats, we’re seeing NPAs, that are now being dragged from their homes in handcuffs, because all they ever wanted to do was participate in democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I want to just be very clear for people. You spearheaded Amendment 4, this historic ballot initiative that restored the right to vote to most state residents with felony convictions. Until then, Florida had been one of only four states — the others were Iowa, Kentucky and Virginia — where people who had committed felonies needed to petition the governor to have their voting rights restored — a grim 19th century legacy of, really, ultimately, slavery, of 19th century laws that passed after the 15th Amendment granted African American men the right to vote. But the Republican-dominated Legislature overturned that and said that people, like you, yourself, Desmond Meade, had to repay every penny of what was owed. Explain what that was and how this leaves — how do people even know what they owe?

DESMOND MEADE: Yeah, that’s something that we’ve been talking about for quite some time, after the passage of Amendment 4. It was a major subject in a lawsuit that followed the enactment of the legislation, the fact that the state does not have a centralized database — right? — to be able to ascertain exactly how much a person may owe, or give someone assurances that, “Listen, you owe so much amount of money, and if you pay that, you’re good to go.” Right? But —

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you owe it for?

DESMOND MEADE: Well, for outstanding fines and fees, such as maybe court costs, restitution, and all various types of fees that the Florida Legislature have allowed the courts to use to collect revenue to keep the doors open. But, Amy, I think that this really speaks to a deeper issue. And the deeper issue is, at the end of the day, if a citizen cannot rely on the state to determine their eligibility, if a citizen cannot rely on the state to determine how much they owe, then that citizen should not be held criminally liable. That citizen should not be drug from their homes in the middle of the night — right? — in handcuffs in the middle of an election.

And it’s very concerning not just to returning citizens, but over the last several days I’ve been receiving calls even from conservatives that are concerned about even the timing of this. You know, if there are people out there who are concerned about the raid on Mar-a-Lago two years from a presidential election, then they should definitely be appalled at what is happening in the middle of an election here in Florida.

AMY GOODMAN: So, why did they think they could vote? If you could explain that? What role did the state play, as you said?

DESMOND MEADE: They played a very important role. Let’s be clear: The burden is on the state to determine whether or not an individual is eligible to register to vote. If I believe that I am eligible to vote, I would go to the supervisor of elections, and I would fill out a voter registration form. The supervisor of elections would then take that form and send it to the secretary of state, where they conduct whatever investigations they need to conduct, they run it through whatever systems they need to run it through, and then make a determination as to whether or not I’m eligible to vote.

In the case of Alachua County, you had an individual who was approached by the supervisor of elections office and said, “Hey, write your name on a piece of paper. We’re going to check to see if you’re eligible to vote. And if you are, we will send you a pamphlet, and then you can go and register to vote.” Well, guess what: This individual, days later, received the pamphlet from the supervisor of elections office saying that that person can vote, and that person registered to vote.

At the end of the day, the burden is on the state. We go to the state, and we fill out an application, and the state needs to make those determinations prior, prior to issuing a voter identification card. And so —

AMY GOODMAN: In the end, do you think these arrests are just going to be thrown out, but what matters is the message that’s sent for tomorrow’s, for Tuesday’s primary, making people, perhaps over a million people, terrified to dare to go to the polls, because what if they’re wrong? What if they somehow don’t have the right to vote?

DESMOND MEADE: Amy, this is unprecedented. And what I’m concerned about is it’s a message that’s not only for Florida, but for this country. It’s a message that is really compelling us to have this conversation, right? And I’m talking about a conversation on both sides of the aisle. This is a time where we can’t be throwing innuendos back and forth, and really look at the deeper question: Is this how we want our democracy to be, where in the middle of an election American citizens are being drug from their home in handcuffs? Right? This is totally unacceptable. Right? And this is happening to both Republicans, it’s happening to Democrats, it’s happening to people that are registering NPA. And so the timing couldn’t be worse than what it is right now. And if it can happen in Florida, it can happen anywhere in this country. And every citizen, no matter what their political persuasions, needs to be very concerned.

There’s also a criminal justice element here. Right? Removing someone from the roster requires the lowest burden of proof, right? And that is the preponderance of the evidence. But when you start talking about taking a citizen’s liberty, I mean, that’s the worst thing that you can do to an individual, is to take their liberty. The burden of proof, the standard of proof is at its highest, and that is beyond a reasonable doubt. Right? And a critical element to these charges is that a person knowingly and willfully registered to vote and voted. Right? In all of these cases, these individuals relied on the state to determine their eligibility, therefore there is no willingness or knowingly element that’s present. But yet these individuals are drug from their homes. Most of these individuals were interviewed by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and were not even aware that they were the subject of a criminal investigation.

And here’s the kicker, Amy. This list that the Florida Department of Law Enforcement is relying on was given to them back in July of 2021. And so, if the state was given a list of people who may not have been eligible to vote or to register to vote over a year ago, why would they wait until the middle of a primary to start making arrests?

AMY GOODMAN: Desmond Meade, we want to thank you for being with us, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition — congratulations on your 10th anniversary — and chair of Floridians for a Fair Democracy.

In recent decades, Spain has often been painted as the only European country without a far right. But even in the 1990s, violent street movements were building their forces — and now they’re entering the country’s political institutions, too.

Journalist and author Miquel Ramos. (Photo: Cristina Candel)

In Spain’s last general election in 2019, the far right achieved its best ever result. With 3.7 million votes (15 percent) and fifty-two seats, Vox became the third-largest party in the Congreso de los Diputados. And it hasn’t stopped advancing. Earlier this year, it joined the government in Castilla y León, Spain’s largest region. If a decade ago Vox didn’t exist, today its leaders appear on prime-time comedy shows — and with general elections slated for 2023, they could soon even be in cabinet.

All this has been a surprise to a certain mainstream mantra. For decades, it had painted Spain as an oasis of democracy, even the only country in Europe without a far right, just because it didn’t show up on election day. But recognizing these forces’ power today is also about facing up to reality. The Spanish far right isn’t just back: it never really went away. Vox is not its only name. That’s something committed anti-fascists have known for over three decades.

As for many others from his generation, anti-fascism is a personal matter for journalist Miquel Ramos, born in Valencia in 1979. A month before Miquel turned fourteen, the eighteen-year-old activist Guillem Agulló was stabbed to death by far-right militants. Ramos knew Agulló through his presence in left-wing demonstrations and political spaces. Indeed, the 1990s were years in which teenagers saw rising fascist violence in the streets. In a year and a half, trans woman Sonia Rescalvo in Barcelona, migrant worker of Dominican origin Lucrecia Pérez in Madrid, and Agulló were all killed.

Ever since then, Ramos began to collect press clippings about the subject, building toward the work he has now published on thirty years of militant opposition to far-right, fascist, and neo-Nazi movements in Spain, entitled Antifascistas: Así se combatió a la extrema derecha española desde los años 90.

Ignacio Pato spoke to Ramos about far-right street movements in Spain, their relationship to the parliamentary right, and how they can be fought.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Compared to older generations, your generation’s relationship to anti-fascism seems to have a distinct, more personal characteristic.

- Miquel Ramos

-

My generation didn’t live through the Transición of the late 1970s, a period marked by the continuity of Francoism in state structures such as the police, and by groups that still advocated for dictatorship.

The fairy tale claimed that fascism had died with Francisco Franco.

But in our teenage years in the 1990s, we did see the manifestations of a far right that had not been so present before. They acted in the streets with violence and impunity. The fairy tale claimed that fascism had died with Francisco Franco. Maybe part of the previous generation that had fought against it didn’t feel attracted by these new groups. But our generation, the one that started to have political concerns at the beginning of the 1990s, did.

It was impossible for many types of people to escape from that far-right violence. A lot of people experienced it, whether they were political militants or not: sometimes you had to be careful just because you hung around certain places.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Can we see different phases in far-right strategies during the last thirty years?

- Miquel Ramos

-

Yes. First, they had some more tribal features associated with skinheads and football hooligans — that was between the mid-1980s and the 2000s. After that, the far right tried to form regular political parties and soften their speech, playing to the gallery.

The third phase was the rise of neofascist social movements influenced by the French Nouvelle Droite, such as Italy’s CasaPound — groups that directly imitate the strategies and symbols of the radical left. The current stage is that we have, for the first time in Spain, a far-right party, Vox, in the institutions. Although the far right disguises itself as democratic, there are still violent groups on the streets.

Although the far right disguises itself as democratic, there are still violent groups on the streets.

The brighter side of the story is that anti-fascism is also organizing. And this movement joins with others such as squatting, anti-globalization, and those who fight for more social, livable neighborhoods. The anti-fascist militant isn’t usually just against fascism.

- Ignacio Pato

-

In Antifascistas, you identify a turning point around November 20, 1988 — the anniversary of Franco’s death — when far-right groups tried to attack the stalls of leftist and anarchist movements in El Rastro, Madrid’s most popular open-air market.

- Miquel Ramos

-

Until then, far-right action was more about reprisals and occasional clashes. However, the assault on El Rastro involved a fascist organization attacking a pretty symbolic space for left-wing people in Madrid. They were already on alert and realized they had to come together and face the problem.

- Ignacio Pato

-

The 1990s were a kind of “years of lead” of continued violence. They began with the killing, on another November 20, of the left-wing Basque MP Josu Muguruza. Groups like Bases Autónomas used violence in the streets, and areas of some cities fell under the far right’s control. For many people, anti-fascism became something more than a political position, for it was also about protecting themselves and their own lives. Do you think today’s society is aware of the real dimensions of what happened then?

- Miquel Ramos

-

I don’t think it is. Days like those scar you. It was a scenario in which you aren’t looking for anything — but it finds you. There were murders, seriously injured people, and others who were forced to beg for their life, to hit back or to preventively attack. It makes you see the far-right problem in a certain way. That threat has been trivialized, for instance, when the media talked about “urban tribes.” Of course, those were not fights for territory: the far right wanted to kill you because of who you were, how you thought, or who you loved. Or who they thought you were, because sometimes victims didn’t have any political link. Crossing glances was enough. My book tries to explain what existed, how people lived with that, and what they did about it. Their testimonies are based on their own experience.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Mainstream media rhetoric, in those years, mainly portrayed the logic of “clashes between different tribes.” For the first time, Nazis made prime-time news. Did this presence sound anti-fascist alarm bells among ordinary citizens, or did it end up whitewashing them?

- Miquel Ramos

-

Media featured a cartoonish far right — very often as a drunk skinhead, while the problem was obviously bigger. The problem was also that some people embraced that cartoon. A lot of Nazis were attracted to the skinhead movement through the movie American History X, the book Diario de un skin, or sensationalist TV reports on football. Some others, it’s true, arrived at anti-fascism through these images, but there was also an attempt within the movement to put a stop to that. For example, Brigadas Antifascistas (BAF) said, “You can’t hang out here, this is political.”

- Ignacio Pato

-

One of the testimonies in the book, from BAF, say this collective was “a steamroller” at the beginning of the millennium. There was an anti-fascist offensive at that time. What were its key elements?

- Miquel Ramos

-

Anti-fascist groups were not only focused on self-defense, but around that time, they got over a “victim” attitude. The mindset changed. For collectives like BAF, the idea was, “There’s no need for them to come for us; we are going for them first.” People who took that initiative saved a lot of other people, in my opinion. It can be criticized from a distance, and the discussion around violent tactics comes through from the whole book, because there has never been a consensus about it. But where an anti-fascist offensive has existed, where people have drawn the line, far-right violence has declined.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Important for another generation of anti-fascists was the murder of Carlos Palomino, a sixteen-year-old stabbed to death at a protest against a neo-Nazi rally in 2007. There was a change in the way the movement communicated and the way it fought to portray the story in media. Some organizations began to show their faces. Somehow, the image of the anti-fascist as an angry young man under a black hood was overcome.

- Miquel Ramos

-

Very often, under those hoods, there were individuals that people wouldn’t imagine. The profile of anti-fascists has always been diverse. The cliché that media created has been the one of a violent “black bloc”–style crew causing trouble. For years, that weighed heavily. Around the time of Carlos Palomino’s murder, there was not just the claim that they killed a minor who had a mother and friends. Some reports insisted on the anti-fascist caricature [of Palomino], and it was a double victimization. And anti-fascism was very clever about showing faces. That helped to dismantle the media’s “both sides” mantra, but not in a complete way, because it persists even now.

The profile of anti-fascists has always been diverse.

- Ignacio Pato

-

What role have police played regarding the far-right problem?

- Miquel Ramos

-

There was not an effective purge of the security forces after Franco’s death. Policemen who had tortured people continued their job until they retired. There was, especially in the 1980s, state terrorism that involved members of those forces. Some of them paid for that with prison time, but others got away with it or even were decorated, as in the well-known case of “Billy el Niño” [the most known torturer and police officer in Franco’s dictatorship, who died of COVID without ever going on trial]. We have always seen Nazis who are sons of police officers or who get arrested but don’t even go to police stations. And don’t forget that their information squads are still talking about “urban tribes” even today.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Some political commentators have connected Vox’s rise to a response to the Catalan independence process and the October 2017 referendum.

- Miquel Ramos

-

Spanish nationalism has always been one of the basic elements of the far right. That always existed — it didn’t need the referendum in order to whip itself into excitement. The question is why the far right was able to capitalize on the campaign against Catalonian self-determination.

Spanish nationalism has always been one of the basic elements of the far right.

The official narrative, the one that came from the authorities, well suited the far right. In demonstrations, there were democrats against the Catalan referendum who didn’t put up any barriers against the far right. Why were people from Communist and Socialist parties sharing banners with Vox? Maybe that narrative was a mistake from the start. Wasn’t there an alternative to police smashing heads on voting day? Why was the message “a por ellos” (“go for them”) institutionalized?

- Ignacio Pato

-

Vox has tried — but so far not managed — to make more of an approach to working-class concerns. Is there a danger, in Spain, of a far right with a more social discourse than Vox itself has?

- Miquel Ramos

-

I don’t really see it now, at a party-political level. I don’t see Vox making a serious approach to social problems concerning workers. Nevertheless, Vox has expanded the Overton window for social movements that imitate the Left and try to use a “class” discourse, as the French Nouvelle Droite did after May ’68 — movements whose narrative turned from attacking the homeless to feeding them.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Former deputy prime minister Pablo Iglesias is one of the interviewees in Antifascistas. This is probably the first time in recent Spanish history that a figure that high up in government can speak on this issue from first-person experience. Anti-fascism was quite an explicit slogan for Podemos in Madrid’s last regional election.

- Miquel Ramos

-

Some people within Podemos come from social movements and have suffered neo-Nazi violence. They’ve got that sensitivity. Pablo Iglesias and equality minister Irene Montero have for a long time had far-right ultras coming to the door of their own home, even sending them bullets in the mail. That’s something that had never happened before.

- Ignacio Pato

-

In the last two years, mental health became a mainstream topic in Spain. This is an issue that the far right never seems to care about, instead making fun of people’s emotional problems. Is mental health a space where anti-fascism, and democracy with it, can make an advance?

- Miquel Ramos

-

The far right is more about bullying than doing politics. It’s based on harassing and knocking down vulnerable groups. Their deeply neoliberal economic program has serious costs for the quality of people’s lives. However much they use the cultural battle as a smokescreen, far-right politics don’t give more rights to the working classes. And this has a cost also at an emotional level. Defending our health — mental health, but also other kinds — is a banner we can raise. The far right doesn’t give a damn about the quality of life of the unprivileged. Anti-fascism is largely based on mutual support and caring for one another. Clearly, we have a moral advantage on this front.

- Ignacio Pato

-

Feminism, anti-racism, LGBTQ movements, housing campaigns, and trade unions allow for a kind of preventive anti-fascism. At the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown, we saw mutual aid groups in a lot of neighborhoods, while the far right didn’t do anything to help anyone. What do you think are their weak spots?

- Miquel Ramos

-

Fascism takes advantage of the neoliberal undermining of class consciousness. They focus not on this social consciousness but on other identities. Their voter is not attracted to economics but by the flag, masculinity, and whiteness.

The far right is more about bullying than doing politics.

The sense of class belonging, which remains widespread still today, used to be a dam against fascism. We aren’t living through the best of times for this consciousness; it’s true. But grassroots struggles in neighborhoods, for housing rights, defending your neighbors, your and your friends’ jobs, maybe other workers’ jobs even though they’re hundreds of miles away from you — all that is absolutely a protective wall against the far right.

- Ignacio Pato

-

What’s your diagnosis of the present situation?

- Miquel Ramos

-

Anti-fascism still counts for a lot among democratic-minded people — it’s part of their DNA. Spain was one of the last European countries where the far right entered parliament, and I think that has increased awareness.

I’ve been asked, in other interviews, if anti-fascism has failed. I’d tell you it hasn’t. The question that needs answering is why people, many of them very young, who fought against the far right were left on their own — so, not what they did wrong, but where the rest of society was. My book wants to pay tribute to people that all too often struggled alone. Still today, there are journalists who don’t know the games the far right plays with media. Even worse, there’s a certain kind of Left that buys into far-right framings.

Anti-fascism has a huge amount of work to do, but a very valuable heritage. We must insist that fascism is not a political option nor a respectable opinion. It impacts many people’s lives. So everyone has to choose what side of history they want to be part of.