Archive for category: #Imperialism #Multipolar

Updated at 11:00 a.m. ET on September 29, 2022

In 1942, answering a pacifist opponent of British involvement in the Second World War, George Orwell replied that “pacifism is objectively pro-fascist.” There have of course been many times in human history when opposition to war has been morally justified, intellectually coherent, and, in the end, vindicated. But the war to defeat fascism during the middle part of the past century was simply not one of them. “This is elementary common sense,” Orwell wrote at the time. “If you hamper the war effort of one side you automatically help that of the other.”

Eight decades later, as a fascistic Russian regime wages war against Ukraine, a motley collection of voices from across the political spectrum has called upon the United States and its allies to adopt neutrality as their position. Ranging from anti-imperialists on the left to isolationists on the right and more respectable “realists” in between, these critics are not pacifists in the strict sense of the term. Few if any oppose the use of force as a matter of principle. But nor are they neutral. It is not sufficient, they say, for the West to cut off its supply of defensive weaponry to Ukraine. It must also atone for “provoking” Russia to attack its smaller, peaceful, democratic neighbor, and work at finding a resolution that satisfies what Moscow calls its “legitimate security interests.” In this, today’s anti-war caucus is objectively pro-fascist.

To appreciate the bizarrely kaleidoscopic nature of this caucus, consider the career of a catchphrase. “Is Washington Fighting Russia Down to the Last Ukrainian?” asked the headline of a column self-published in March by Ron Paul, the former Republican congressman and presidential candidate. It was a strange question for Paul to be posing just three weeks into President Vladimir Putin’s unjustifiable and unforgivable invasion, especially considering the extraordinary lengths to which the Biden administration had gone to avoid “fighting Russia.”

[Tom Nichols: Two battles for democracy]

Even stranger than Paul’s assertion that the U.S. was goading Ukrainians into sacrificing themselves on the altar of its Russophobic bloodlust, though, has been the proliferation of his specious talking point across the ideological spectrum.

Ten days after Paul accused his country of treating Ukrainians as cannon fodder, the retired American diplomat Chas Freeman repeated the quip. “We will fight to the last Ukrainian for Ukrainian independence,” Freeman declared sarcastically—even as he excused Russia’s “special military operation” as an understandable reaction to being “stiff-armed” by the West on the “28-year-old demands that NATO stop enlarging in the direction of Russia.” Freeman, a former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia and a senior fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute, made these remarks in an interview with The GrayZone, a self-described “independent news website dedicated to original investigative journalism and analysis on politics and empire.”

Although The GrayZone would characterize itself as an “anti-imperialist” news source, the opaquely financed publication is highly selective in the empires it chooses to scrutinize; it is difficult to find criticism of Russia or China—or any other American adversary—on its site. A more accurate descriptor of its ideological outlook is “campist,” denoting a segment of the sectarian far left that sees the world as divided into two camps: the imperialist West and the anti-imperialist rest.

Freeman, who served as Richard Nixon’s interpreter during his 1972 visit to China, seemed to feel at home in The GrayZone. In that Manichaean domain—one that lacks, naturally, any shades of gray—no anti-Western tyrant is too brutal for fawning adulation, and America is always to blame. A Republican foreign-policy hand in conversation with a fringe leftist website might seem like an odd pairing, but Freeman has a fondness for dictators.

[Dominic Tierney: The rise of the liberal hawks]

In 2009, when Freeman was appointed to serve on the National Intelligence Council during the first year of the Obama administration, a series of leaked emails revealed a window into his worldview. Observing the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Freeman praised the Chinese Communist Party for its bloody crackdown on peaceful student demonstrators; his only criticism of its dispersal of this “mob scene” was that it had been “overly cautious” in displaying “ill-conceived restraint.” It is quite something to read a retired American diplomat criticizing the Chinese regime for being too soft during the Tiananmen massacre, but such views are not as aberrational as they sound. Within the school of foreign-policy “realism,” notions of morality are seen as quaint distractions from the real business of great-power politics.

In April, it was Noam Chomsky’s turn to recite the Pauline mantra in a podcast with the editor of Current Affairs, a leftist magazine. Going out of his way to praise Freeman as “one of the most astute and respected figures in current U.S. diplomatic circles,” the world’s most famous radical intellectual endorsed the crusty veteran of realist GOP administrations for characterizing American policy in Eastern Europe as “fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian.”

From Chomsky’s mouth to Putin’s ears.

“A great deal is being said about the United States’ intention to fight against Russia ‘to the last Ukrainian’—they say it there and they say it here,” the Russian president mused the following week, prefacing his mention of the gibe with his own version of that Trumpian rhetorical flourish, “A lot of people are saying.” That same month, an American Conservative article by Doug Bandow of the libertarian Cato Institute was headlined “Washington Will Fight Russia to the Last Ukrainian,” denying Ukrainians any agency in their own struggle by answering the question Paul had rhetorically asked.

Soon after, the dean of realist international-relations theorists, the University of Chicago scholar John Mearsheimer, used the line as though he’d just thought of it. By then, the argument that America was “fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian” had ping-ponged between both ends of the ideological spectrum an astonishing number of times. The point for the anti-imperialist left and the isolationist right, as well as the realist fellow travelers hitched to each side, was that blame for the conflict lies mainly with the U.S., which is using Ukraine as a proxy for its nefarious interventionism in Moscow’s backyard.

That the fringe left would blame America—which it views as the source of all capitalist exploitation, military aggression, and imperialist evil in the world—for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is predictable. It blames America for everything. When, two days after the Russian invasion began on February 24, the Democratic Socialists of America called upon “the US to withdraw from NATO and to end the imperialist expansionism that set the stage for this conflict,” mainstream Democrats condemned the statement. More significant has been the position taken by mainstream realists, who similarly fault the West for somehow “provoking” Russia into waging war on its neighbor. These politically disparate forces share more than a talking point. They also have a worldview in common.

Consider America’s leading realist think tank, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. This “transpartisan” group enjoyed great fanfare upon its founding, in 2019, with seed funding from the libertarian Charles Koch and the left-wing George Soros. After two decades of “forever wars,” here at last was an ideologically diverse assortment of reasonable, sober-minded experts committed to pursuing a “foreign policy of restraint.” But counseling inaction as a rapacious, revisionist dictatorship wages total war on its smaller, democratic neighbor had a whiff of appeasement for at least one of Quincy’s fellows, leading to a split within the organization.

[From the May 2022 issue: There is no liberal world order]

“The institute is ignoring the dangers and the horrors of Russia’s invasion and occupation,” Joe Cirincione, a nuclear non-proliferation expert and one of the group’s leading left-of-center scholars, said upon his resignation this summer, adding that Quincy “focuses almost exclusively on criticism of the United States, NATO, and Ukraine. They excuse Russia’s military threats and actions because they believe that they have been provoked by U.S. policies.”

The moral myopia Cirincione identifies is an essential trait of the new online magazine Compact, where self-styled anti-woke Marxists and Catholic theocrats unite in their loathing of classical liberal values at home and their opposition to defending those values abroad. In an article titled “Fueling Zelensky’s War Hurts America,” the left-wing writer Batya Ungar-Sargon took issue with the U.S. supplying defensive weaponry to Kyiv, arguing that resources devoted to supporting Ukrainians would be better spent helping economically disadvantaged Americans.

Pushing the United States to prioritize the needs of its poorest citizens, even if that means forgoing its responsibilities for maintaining the European security order, is at least an intellectually defensible position (if a shortsighted and reductive one). But Ungar-Sargon also went out of her way to give credence to Russia’s specious territorial claims.

“If Ukraine’s territorial integrity were of such immense national interest,” she wrote, “surely we would have climbed the rapid-escalation ladder back in 2014, when Moscow invaded and annexed Crimea—a move that a referendum found was popular among Crimeans.” The plebiscite Ungar-Sargon endorsed was held under Russian gunpoint to provide a legal fig leaf for the first armed annexation of territory on the European continent since World War II. She also identified Donetsk and Luhansk—the two Russian-backed separatist enclaves in Eastern Ukraine that Putin recognized as puppet states on the eve of his invasion and where he has now held similarly meaningless referenda annexing them to Russia—as “independent republics,” conferring a legitimacy that was in marked contrast to the way she referred dismissively to “the United States and its European satrapies.”

Many commentators have likened Volodymyr Zelensky to Winston Churchill for his charismatic resistance to foreign invaders and his ability to raise the morale of his people. In light of this popular association, the headline that the editors of Compact devised for Ungar-Sargon’s apologia—“Zelensky’s War”—is nauseating, blaming the victim while seeming to evoke the title of a notorious book by the Holocaust-denying historian David Irving, Churchill’s War.

Condemning the U.S. and its allies for the unfolding tragedy in Ukraine requires one to ignore or downplay a great deal of Russian misbehavior. This is a characteristic that unites left-wing anti-imperialists, right-wing isolationists, and the ostensibly more respectable “realists.”

“Russian President Vladimir Putin, the argument goes, annexed Crimea out of a long-standing desire to resuscitate the Soviet Empire, and he may eventually go after the rest of Ukraine as well as other countries in Eastern Europe,” Mearsheimer wrote in a 2014 essay titled “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault.” “But this account is wrong.” Eight years on, as Russian forces marched toward Kyiv and Putin issued vague threats of nuclear escalation, Mearsheimer made no acknowledgment of how very wrong his own earlier, sanguine assessment of Putin’s intentions had been.

[James Kirchick: Being gay was the gravest sin in Washington]

“We invented this story that Putin is highly aggressive and he’s principally responsible for this crisis in Ukraine,” he told The New Yorker a week into the invasion. Putin’s apparent goal of overthrowing Zelensky and installing a puppet regime would not be an example of “imperialism,” Mearsheimer argued, and was meaningfully different from “conquering and holding onto Kyiv.” All of this linguistic legerdemain would surely come as news to the Czechs, Poles, Slovaks, and other peoples of the region who once suffered under the Russian imperial yoke.

As evidence of Russian war crimes against Ukrainian civilians mounts, Mearsheimer has cleaved to his position that NATO enlargement is to blame for the war. “I think all the trouble in this case really started in April, 2008, at the NATO Summit in Bucharest, where afterward NATO issued a statement that said Ukraine and Georgia would become part of NATO,” he also told The New Yorker. Although the NATO communiqué did express the alliance’s hope that the two former Soviet republics would become members at some indefinite point in the future, it came after France and Germany had successfully blocked a proposal by the Bush administration to offer Ukraine and Georgia an actual path to membership. But even if the U.S. had made such a promise, how would that justify the invasion and occupation of Ukraine? Mearsheimer also ignores the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, according to which the United States, Britain, and Russia guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity in exchange for Ukraine surrendering its nuclear weapons. This concord lasted for 20 years, until Putin abrogated it by invading and occupying Crimea.

Even more obtuse are the excuses for Russian aggression made by Mearsheimer’s fellow academic realist, the Columbia University professor Jeffrey Sachs. Sachs has worked as an adviser to a host of international institutions, such as the World Health Organization, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, as a development economist. Unlike Mearsheimer, he has no particular expertise in foreign political affairs, but this has not stopped him from pronouncing on geopolitical issues. Last December, as Russia was amassing its forces on Ukraine’s border, Sachs suggested that “NATO should take Ukraine’s membership off the table, and Russia should forswear any invasion.” This ignored the fact that Russia had already invaded the country in 2014.

Seeking to explain “the West’s false narrative” about Ukraine after the war began, Sachs noted, “Since 1980 the US has been in at least 15 overseas wars of choice (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Panama, Serbia, Syria and Yemen to name just a few), while China has been in none, and Russia only in one (Syria) beyond the former Soviet Union.” This sentence contains two significant qualifications. First, Sachs’s counting only those “wars of choice” that Russia waged “beyond the former Soviet Union” implies that its invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 were permissible through some sort of Cold War–continuity droit de seigneur. Second, Sachs’s selection of 1980 as the starting point for his comparison conveniently excludes the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which began in December 1979 and became the Red Army’s own forever war, lasting almost 10 years and playing a crucial role in the Soviet Union’s demise.

Russia’s war against Ukraine has exposed the incompetence of the Russian military and the hubris of President Putin. It has also revealed the bravery and resilience of the Ukrainian people, who, contrary to Ron Paul’s ambulatory talking point, had no need of any American to prod or gull them into defending their homeland. Here in the U.S., the war has also exposed the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of an ideologically diverse set of foreign-policy commentators: the “anti-imperialists” who routinely justify blatant acts of imperial conquest, and the “realists” who make arguments unmoored from reality.

“Five months after carrying Sergeant Emory down the stairs in Kamaliyah,” he could no longer shake off all the hurt and harm of war. On his third deployment in Iraq, Adam Schumann was done.

His war had become unbearable. He was seeing over and over again his first kill disappearing into a mud puddle, looking at him as he sank. He was seeing a house that had just been obliterated by gunfire, a gate slowly opening, and a wide-eyed little girl about the age of his daughter peering out. He was seeing another gate, another child, and this time a dead-aim soldier firing. He was seeing another soldier, also firing, who afterward vomited as he described watching head spray after head spray through his magnifying scope. He was seeing himself watching the vomiting soldier while casually eating a chicken-and-salsa MRE.

He was still tasting the MRE.

He was still tasting Sergeant Emory’s blood.

Schumann, diagnosed with depression and PTSD, and thinking about suicide, was sent home.

David Finkel, an American journalist who embedded with the 2-16 Infantry Battalion of the US Army during the “surge” in Iraq, beginning in the spring of 2007, tells Schumann’s story in The Good Soldiers. This Pulitzer Prize-winning account of war reads like a diary of specific days and moments—the excitement and patriotism, the gore (of IEDS, of dead bodies, of killing), the anger and the hatred, counterinsurgency tasks like handing out soccer balls, and the psychological pain of the (mostly) very young soldiers who carry it out. In Finkel’s telling, Schumann is not exceptional, in that the military’s own studies “suggested that 20 percent of soldiers deployed to Iraq experienced symptoms of PTSD.” He also reports that “in the culture of the army, where mental illness has long been equated with weakness,” such diagnoses were not easily recognized or accepted. There remained “a lingering suspicion of any diagnosis for which there wasn’t visible evidence.” And yet injuries for which there is no visible evidence are ubiquitous among troops and veterans of these wars—as recounted by journalists and scholars, as repre- sented on TV shows and in movies, as described in novels and poetry written by veterans who have returned from war. And in a discourse that passes over the military’s primary concern with force protection in favor of talk of a national moral obligation, those so-called invisible injuries are examined and explained to the public at large—so they can be understood and healed, so that proper attention to “the war” is paid on the home front.

David Wood, another American journalist (and author of the book What Have We Done, discussed in Chapter 5), embedded with a Marine unit in Afghanistan and some years later, in March 2014, published a lengthy essay on moral injury in the Huffington Post. He opens with the following questions: “How do we begin to accept that Nick Rudolph, a thoughtful, sandy- haired Californian, was sent to war as a 22-year-old Marine and in a desperate gun battle outside Marjah, Afghanistan, found himself killing an Afghan boy? That when Nick came home, strangers thanked him for his service and politicians lauded him as a hero?” Wood continues,

Can we imagine ourselves back on that awful day in the summer of 2010, in the hot firefight that went on for nine hours? Men frenzied with exhaustion and reckless exuberance, eyes and throats burning from dust and smoke, in a battle that erupted after Taliban insurgents castrated a young boy in the village, knowing his family would summon nearby Marines for help and the Marines would come, walking right into a deadly ambush.

In case we cannot imagine it, Wood does so for us: “Nick … spots somebody darting around the corner of an adobe wall, firing assault rifles at him and his Marines. Nick raises his M-4 carbine. He sees the shooter is a child, maybe 13. With only a split second to decide, he squeezes the trigger and ends the boy’s life.” As for Nick, he struggles with the dilemma: “He was just a kid. But … I’m trying not to get shot and I don’t want any of my brothers getting hurt … You know it’s wrong. But … you don’t have a choice.” This, as Wood informs his readers, is the essence of war trauma as it frequently appears among soldiers who have fought these latest American wars.

In choosing this particular event to open a series of essays on moral injury, Wood ascribes a young American Marine’s trauma to a decision made during a battle reportedly instigated by a barbaric act. Stories of barbaric acts, culturally incommensurable values, and an enemy who does not respect the laws of war characterize many accounts of the wars on terror and the kinds of war trauma, including moral injury, that come in tow. The way Wood understood the situation in Afghanistan, “some ugly aspects of the local culture and the brutality of the Taliban rubbed American sensibilities raw, setting the stage for deeper moral injury.” He quotes Rudolph as an example:

You see the Afghan tradition of basically boys dance for grown men and they give them money and the guy who gives the most money gets to take the boy home. We are partnering with guys who are basically screwing the neighbors’ kids, 6- and 7-year-olds, and we are supposed to grin and bear it because our cultures don’t mesh? … When I really want to fuckin’ strangle those dudes?”

Other kinds of stories about moral injury are also told, some more critical politically, such as the one recounted by an Army veteran at a conference on moral injury discussed in the previous chapter. He recalled being shaken to the core by his own cruelty toward an Iraqi child. An adult came over to protect the child, and the speaker did not recognize himself in the man’s terrified eyes. Moral injuries can result as well from seemingly banal acts of carrying out an occupation—kicking in doors, scaring the family, and frequently enough finding no insurgents at home. Soldiers tell of mistaking noncombatants for insurgents in the heat of battle or having no opportunity to discriminate, at a checkpoint, for example, with a car speeding at them that fails to stop. For the most part, these narratives are framed by a set of shared assumptions about the inevitable moral ambiguities of counterinsurgency wars. Occasionally they are offered—almost exclusively by veterans—as a political critique of America’s wars, which they now oppose.

War stories told about combat trauma by journalists and scholars who were “embedded” with American soldiers in the war zone or spent time with veterans back home are generally narrated from the soldiers’ point of view. Readers are typically admonished to recognize their obligation to face the realities of war, to confront rather than evade the question of what “we” have sent “them” to do, while, at the same time typically sanitizing the extent and brutality of American military aggression. Wood describes the “scowling young killers of Uganda and Congo” he encountered previously as a war correspondent; a few pages later, he writes of American troops carrying “immense responsibility”; handling it “well and with passion.” “At war, I have seen Americans at their best. In a very personal way, I admire and honor their service.” One has to wonder what he has seen and heard in the midst of battle and in its aftermath that he leaves out of his story. A parallel question might be asked of recent anthropological accounts of the war, narrated from the soldiers’ points of view, in which case ethnography as method operates to some extent as the functional equivalent of embed- ded journalism. What might the soldiers with whom various anthropologists have “embedded” stateside chosen not to share?

In “The Life and Lonely Death of Noah Pierce,” Ashley Gilbertson takes a different tack in her account of the kinds of actions, sensibilities, and affects that drive combat, as well as its horrors and traumatic afterlives. Noah Pierce was an Army veteran who committed suicide in 2007 and whose war experi- ence Gilbertson reconstructs based on his diary and letters home he wrote from Iraq. She wants to know what pushed Pierce to suicide. “It could have been the memory of the Iraqi child he crushed under his Bradley. ‘It must have been a dog,’ he told his commanders. It could have been the unarmed man he shot point-blank in the forehead during a house-to-house raid, or the friend he tried madly to gather into a plastic bag after he had been blown to bits by a roadside bomb, or … it could have been the doctor he killed at a checkpoint.” The “moral ambiguity of house-to-house raids” haunted Pierce. He wrote about how he and others in his platoon would “blow off steam” by “abusing prisoners.” “I’m so pissed off right now,” he wrote to his parents, relating how “beatin’ a s********* unconscious would help but we will get in serious trouble if it happens again.” He stole money from Iraqi civilians and sent it back to his parents. “Well staying here as part of the postwar occupation has had one good impact on me,” he wrote in another letter.

I no longer regret what I did during the war. I have so much hatred in me I could go murder more s********** and I would just smile. That goes for almost everyone here. We had sympathy for them after the war but now we have absolutely nothing but hatred for them. We should have killed more during the war. I let all kinds of “‘innocent” people go when I should have just mowed them down.

Or as he recounted in his diary,

So far, this has been the worst month of my life. With all this work I have been ready to snap. I don’t know how much I can take. A car pissed me off last night. The fucker kept flashing me and when he pulled off the road I almost ran him over. I changed my mind though, I could have gotten away with killing that mother-fucker though. My transmission was going out and I could have blamed it on that. I am just waiting for a good opportunity though. I am just waiting for the chance where I know people will die. I am not going to swerve at them, but I am not going to avoid it like I have been. The only reason I have avoided it so far is there have been women and children in the cars coming at me.

“I am a bad person,” he bemoans.

All books are 40% off as part of our Student Reading Sale. Ends September 30 at 11:59PM EST. See all our student reading lists here.

At the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos (Switzerland) on May 23, 2022, former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger made some remarks about Ukraine that struck a nerve. Rather than be caught up “in the mood of the moment,” Kissinger said, the West—led by the United States—needs to enable a peace agreement that satisfies the Russians. “Pursuing the war beyond [this] point,” Kissinger said, “would not be about the freedom of Ukraine, but a new war against Russia itself.” Most of the commentary from the Western foreign policy establishment rolled their eyes and dismissed Kissinger’s comments. Kissinger, no peacenik, nonetheless indicated the great danger of escalation towards not only the establishment of a new iron curtain around Asia but perhaps open—and lethal—warfare between the West and Russia as well as China.

The post The United States Is Waging A New Cold War: A Socialist Perspective appeared first on PopularResistance.Org.

Sergei Vlasov/Russian Orthodox Church Press Service via AP

- Patriarch Kirill I said Russian soldiers who die in the war will be absolved of “sins.”

- The Sunday sermin came days after Russia announced the mobilization of 300,000 troops.

- Kirill is known to support Russian President Vladimir Putin and the invasion of Ukraine.

The leader of the Russian Orthodox Church compared dying in the war against Ukraine to an act of “sacrifice” and that doing so absolved soldiers of their “sins.”

Patriarch Kirill I made his remarks on Sunday, days after Russia announced a “partial mobilization” of troops, and men continue to be seen fleeing the country to avoid the draft.

—Matthew Luxmoore (@mjluxmoore) September 26, 2022

“Many are dying on the fields of internecine warfare,” Kirill said, according to a translation by Reuters. “The Church prays that this battle will end as soon as possible, so that as few brothers as possible will kill each other in this fratricidal war.”

“But at the same time, the Church realizes that if somebody, driven by a sense of duty and the need to fulfill their oath … goes to do what their duty calls of them, and if a person dies in the performance of this duty, then they have undoubtedly committed an act equivalent to sacrifice. They will have sacrificed themselves for others. And therefore, we believe that this sacrifice washes away all the sins that a person has committed,” he said, according to Reuters.

Kirill is known to be a supporter of President Vladimir Putin and of the invasion of Ukraine.

He previously justified the war as a fight against “excess consumption” and “gay parades” infiltrating Ukraine, according to The Orthodox Times. Kirill has also described Putin’s leadership as a “miracle of God.”

Putin announced on September 21 a “partial mobilization” of 300,000 military troops — an act seen as an escalation of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Almost immediately, one-way flight tickets out of Russia sold out and internet searches for “how to leave Russia” spiked in the country.

Lines of cars have packed Russia’s borders with Georgia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and other countries, according to The Associated Press.

On Friday, investigators working for the United Nations delivered a sobering statement to the UN Human Rights Council detailing evidence of Russian war crimes committed as part of the nation’s ongoing occupation of Ukraine, including the rape of children, torture, beatings, electric shocks, forced nudity, and the disappearance of people taken into Russian detention.

These findings came as part of the first official update from three experts who were asked to investigate allegations of war crimes that first arose this spring, soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Their investigation focused on four areas of Ukraine—Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kharkiv and Sumy—where horrific reports of alleged war crimes, including the rape of civilians and summary executions, began to emerge between late February and March of this year as Russia began its war. Friday’s report is the first from the UN to bring forth extensive evidence backing up these allegations, including through interviews with dozens of victims and witnesses.

“We are concerned by the suffering that the armed conflict in Ukraine has imposed on the civilian population,” Erik Mose, chairman of the investigative commission, told the UN.

Mose’s team told the UN they’d interviewed 150 victims and witnesses across 27 towns and settlements, studied documents, and inspected graves, weapon remnants, and places where detention and torture occurred. Across all this research, they found:

- Russia engaged in attacks, including air strikes and rocket-launches, where the country made no effort to distinguish between civilians and combatants.

- Evidence of widespread executions: “We were struck by the large number of executions in the areas that we visited,” the investigators said in their report. The group said it is investigating executions in 16 of the locations it visited, and has collected evidence of such acts that include: “hands tied behind backs, gunshot wounds to the head, and slit throats.”

- Widespread sexual violence towards adults and children: “In the cases we have investigated, the age of victims of sexual and gendered-based violence ranged from four to 82 years,” investigators noted. They said that they’d found cases where relatives were forced to watch Russian soldiers commit these crimes. They’ve also documented situations where children were raped and tortured.

- Evidence of torture and unlawful confinement: Investigators said that they’d heard from victims who were tortured after their detention by Russian forces in Ukraine. Some said they were then forcibly taken over national lines to Russia and detained in prisons there—backing up allegations of forced migrations that came out as early as March. Witnesses spoke of beatings, electrical shocks, and forced nudity that occurred in detention.

This UN report came out the day before the seven-month anniversary of Russia instigating the war in Ukraine, and at a moment when the conflict is at yet another inflection point. Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin declared a partial mobilization for men of military age in Russia—what effectively amounts to a military draft of 300,000 people to replenish the manpower Putin needs to continue fighting against Ukrainians. His announcement spurred attempts by swaths of men and families to flee Russia.

Lines to cross into the neighboring countries of Finland, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Georgia stretched for miles this week, while flights to nearby countries quickly sold out. Videos circulated on social media that appeared to show hours-long traffic jams of cars waiting to cross land borders out of Russia.

This is what is happening now on the border between #Russia and #Georgia.

Video: Ekho Kavkaza pic.twitter.com/3eFznx3dvf

— NEXTA (@nexta_tv) September 21, 2022

Long lines of vehicles have formed at a border crossing between Russia’s North Ossetia region and Georgia after Moscow announced a partial military mobilization. Report by @RTavisupleba pic.twitter.com/LyhxLUYRv3

— Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (@RFERL) September 22, 2022

Several Russian news sources, including Lenta and RBK, reported that flights to countries that allow visa-free travel from Russia, including Armenia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, had sold out within minutes of Putin’s mobilization announcement on Wednesday. The few remaining tickets that reporters at RBK could find online, for example, were for dates in late September, and cost upwards of $1,300.

“I am strongly against this war,” a male software engineer told CNN after successfully making it to Turkey from Russia. “Everyone I know is against it. My friends, my family, nobody wants this war. Only politics want this war.”

He added: “The only plan is to survive. I’m just scared”

Why aren’t we hearing more about corporate surveillance of employees in the United States?

Today’s New York Times has a story about Russia’s powerful internet regulator, Roskmnadzor, whose collection of personal data about average Russians has, in the Times’s words, “catapulted Russia, along with authoritarian countries like China and Iran, to the forefront of nations that aggressively use technology as a tool of repression.”

A few weeks ago, the Times ran a story about China’s collection of personal data on its citizens through phone-tracking devices, voice prints, one of the largest DNA databases in the world, facial recognition technology, and more than half of the world’s nearly one billion surveillance cameras.

This is important and useful reporting. But pardon me if I ask an impertinent question: Why aren’t we hearing more about corporate surveillance of employees in the United States? Or about corporate surveillance of Americans in general? Or how this corporate surveillance is being used by the US and state governments?

Even if Russia’s and China’s surveillance states are far more dangerously intrusive than America’s surveillance capitalism, shouldn’t we know more about how the same or very similar technologies are being utilized here?

Since I was secretary of labor, I’ve seen American companies load up on monitoring software — to watch what workers are doing every minute of the day. Workers are now subject to trackers, scores, and continuous surveillance of their hands, eyes, faces, and bodies. And increasingly, they’re paid only for the minutes (or seconds) when the systems detect they’re actively working.

Kroger cashiers, UPS drivers, and millions of others are monitored by the minute. Amazon measures seconds. J.P. Morgan — the largest bank in the United States — tracks how its workers spend time, from making phone calls to composing emails. At UnitedHealth Group, low keyboard activity can affect compensation and sap bonuses. In Amazon warehouses, some workers don’t get enough time to go to the bathrooms. ESW Capital, a Texas-based business software company, tracks workers in 10-minute intervals during which — at some moment that workers can’t anticipate — cameras take snapshots of their faces and screens.

“Digital productivity monitoring” — isn’t that an innocent-sounding phrase? — is spreading even to white-collar jobs requiring graduate degrees. Radiologists get scoreboards showing “inactivity” time and comparing productivity to their colleagues’. Doctors and nurses describe increasing electronic surveillance over workdays. Even lawyers are being closely monitored.

Firms selling all this monitoring technology gush with testimonials from supervisors describing newfound powers of “near X-ray vision” into what workers are doing other than working: watching porn, playing video games, using bots to mimic typing, two-timing. Dystopia now!

Russia’s and China’s growing surveillance systems seem more dangerous and intrusive than America’s increasing surveillance of our workers because the information Russia and China collect can stifle dissent.

But are the surveillance systems really that far apart? Big corporations that gather loads of data on exactly what their workers do all day (and sometimes into the night) — including in their purview the growing ranks of remote or gig workers — can stifle workers’ efforts to form labor unions or show any disgruntlement at all.

Russia’s and China’s surveillance of their inhabitants and America’s surveillance of our workers are starting to overlap because the technologies are starting to overlap.

A technology company in eastern China even designs “smart” cushions for office chairs that record when workers are absent from their desks. How long before we see smart cushions in American offices?

And more and more, we’re being surveilled without knowing it. Delta Air Lines boasts that its Atlanta airport’s Terminal F is the “first biometric terminal” in the United States where passengers can use facial recognition technology “from curb to gate.”

The Financial Times reports that a Microsoft facial recognition training database of 10 million images drawn from the internet without anyone’s knowledge is utilized by agencies that include the United States and Chinese military.

A new joint report from the Associated Press and Electronic Frontier Foundation highlights a major surveillance tool, known as “Fog Reveal,” now being used by dozens of local law enforcement agencies across the United States to collect personal data without a warrant. The tool makes use of advertising data — including location, timestamp, and a unique advertising ID tied to individual devices — to construct a searchable database that enables law enforcement to either track an individual device or see which devices passed through a certain area.

Where does this end?

A few years back, Mark Zuckerberg predicted that “Facebook will know every book, film, and song you ever consumed, and its predictive models will tell you what bar to go to when you arrive at a strange city, where the bartender will have your favorite drink waiting.”

Well, that day has just about arrived.

Google’s Eric Schmidt has said, “We know where you are. We know where you’ve been. We more or less know what you’re thinking about.”

With Google using my search data and its high-tech trucks surveilling my neighborhood, I’m sure Schmidt is right.

As Shoshana Zuboff noted in her brilliant The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, we once celebrated these new digital services as free but we are learning that the platforms are hyper-velocity global bloodstreams into which almost anyone may introduce a dangerous virus without a vaccine, or from which big corporations and government can draw anything they’d like to know about us.

I’m not so sure we should be so disdainful of Russia’s and China’s surveillance systems, given what’s happening in the United States.

Isn’t it time we got serious about protecting our freedom from being watched, monitored, examined, and exposed? Otherwise, the surveillance state and surveillance capitalism merge — and we’ll have no place to hide.

Stan Cox, A War on the Earth?

In so many ways, you still wouldn’t know it — not, that is, if you focused on the Pentagon budget or the economic growth paradigm that rules this country and our world — but this planet is in a crisis of a sort humanity has never before faced. Whether you’re considering heat in the American West, floods in Pakistan, the drying up of the Yangtze River in China, record drought in Europe, or the unparalleled warming of the Arctic, we are, as scientists have been pointing out (and ever more of us ordinary people have noted), in an increasingly “uncharted territory of destruction.” In the process, ever more climate “tipping points” stand in danger of being passed as the overheating of this planet becomes the stuff of everyday life.

And sadly, despite all that, Vladimir Putin’s Russia brutally invaded Ukraine, ensuring the release of yet more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere as, among other things, various European countries were forced to turn to greater coal use. Meanwhile, the U.S. and China, the two largest greenhouse gas emitters, are now heading into what’s being called, without the slightest sense of irony, a “new cold war.” In the process, responding to House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi’s decision to visit Taiwan, China recently suspended planned climate talks between the two countries.

Today, TomDispatch regular Stan Cox, author of The Green New Deal and Beyond: Ending the Climate Emergency While We Still Can, explores just what it means, in climate terms, for the U.S., no matter the administration, to pour ever more taxpayer dollars into the Pentagon and the rest of the national security state. Yes, it’s long been commonplace to claim that war is hell (and if you don’t believe that, just check out the nightmare in Ukraine right now). One thing should be ever clearer: sadly enough, that way of life is now all too literally the path to hell. Let Cox explain. Tom

The Nightmare of Military Spending on an Overheating Planet – A Big Carbon Bootprint and a Giant Sucking Sound in the National Budget

On October 1st, the U.S. military will start spending the more than $800 billion Congress is going to provide it with in fiscal year 2023. And that whopping sum will just be the beginning. According to the calculations of Pentagon expert William Hartung, funding for various intelligence agencies, the Department of Homeland Security, and work on nuclear weaponry at the Energy Department will add another $600 billion to what you, the American taxpayer, will be spending on national security.

That $1.4 trillion for a single year dwarfs Congress’s one-time provision of approximately $300 billion under the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for what’s called “climate mitigation and adaptation.” And mind you, that sum is to be spent over a number of years. In contrast to the IRA, which was largely a climate bill (even if hardly the best version of one), this country’s military spending bills are distinctly anti-human, anti-climate, and anti-Earth. And count on this: Congress’s military appropriations will, in all too many ways, cancel out the benefits of its new climate spending.

Here are just the three most obvious ways our military is an enemy of climate mitigation. First, it produces huge quantities of greenhouse gases, while wreaking other kinds of ecological havoc. Second, when the Pentagon does take climate change seriously, its attention is almost never focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions but on preparing militarily for a climate-changed world, including the coming crisis of migration and future climate-induced armed conflicts globally. And third, our war machine wastes hundreds of billions of dollars annually that should instead be spent on climate mitigation, along with other urgent climate-related needs.

The Pentagon’s Carbon Bootprint

The U.S. military is this globe’s largest institutional consumer of petroleum fuels. As a result, it produces greenhouse gas emissions equal to about 60 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. Were the Pentagon a country, those figures would place it just below Ireland and Finland in a ranking of national carbon emissions. Or put another way, our military surpasses the total national emissions of Bulgaria, Croatia, and Slovenia combined.

A lot of those greenhouse gases flow from the construction, maintenance, and use of its 800 military bases and other facilities on 27 million acres across the United States and the world. The biggest source of emissions from actual military operations is undoubtedly the burning of jet fuel. A B-2 bomber, for instance, emits almost two tons of carbon dioxide when flying a mere 50 miles, while the Pentagon’s biggest boondoggle, the astronomically costly F-35 combat aircraft, will emit “only” one ton for every 50 miles it flies.

Those figures come from “Military- and Conflict-Related Emissions,” a June 2022 report by the Perspectives Climate Group in Germany. In it, the authors express regret for the optimism they had exhibited two decades earlier when it came to the reduction of global military greenhouse gas emissions and the role of the military in experimenting with new, clean forms of energy:

In the process of us writing this report and looking at our article written 20 years ago, the initial notion of assessing military activities… as potential ‘engines of progress’ for novel renewable technologies was shattered by the Iraq War, followed by the horror of yet another large-scale ground war, this time in Europe… All our attention should be directed towards achieving the 1.5° target [of global temperature rise beyond the preindustrial level set at the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015]. If we fail in this endeavor, the repercussions will be more deadly than all conflicts we have witnessed in the last decades.

In March, the Defense Department announced that its proposed budget for fiscal year 2023 would include a measly $3.1 billion for “addressing the climate crisis.” That amounts to less than 0.4% of the department’s total spending and, as it happens, two-thirds of that little sliver of funding will go not to climate mitigation itself but to protecting military facilities and activities against the future impact of climate change. Worse yet, only a tiny portion of the remainder would go toward reducing the greenhouse-gas emissions or other environmental damage the armed forces itself will produce.

In a 2021 Climate Adaptation Plan, the Pentagon claimed, however vaguely, that it was aiming for a future in which it could “operate under changing climate conditions, preserving operational capability, and enhancing the natural and manmade systems essential to the Department’s success.” It projected that “in worst-case scenarios, climate-change-related impacts could stress economic and social conditions that contribute to mass migration events or political crises, civil unrest, shifts in the regional balance of power, or even state failure. This may affect U.S. national interests directly or indirectly, and U.S. allies or partners may request U.S. assistance.”

Sadly enough, however, as far as the Pentagon is concerned, an overheated world will only open up further opportunities for the military. In a classic case of projection, its analysts warn that “malign actors may try to exploit regional instability exacerbated by the impacts of climate change to gain influence or for political or military advantage.” (Of course, Americans would never act in such a manner since, by definition, the Pentagon is a benign actor, but will have to respond accordingly.)

The CIA and other intelligence agencies seem to share the Pentagon’s vision of our hotter future as a growth opportunity. A 2021 climate risk assessment by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) paid special attention to the globe’s fastest-warming region, the Arctic. Did it draw the intelligence community’s interest because of the need to prevent a meltdown of the planet’s ice caps if the Earth is to remain a livable place for humanity? What do you think?

In fact, its authors write revealingly of the opportunities, militarily speaking, that such a scenario will open up as the Arctic melts:

Arctic and non-Arctic states almost certainly will increase their competitive activities as the region becomes more accessible because of warming temperatures and reduced ice. … Military activity is likely to increase as Arctic and non-Arctic states seek to protect their investments, exploit new maritime routes, and gain strategic advantages over rivals. The increased presence of China and other non-Arctic states very likely will amplify concerns among Arctic states as they perceive a challenge to their respective security and economic interests.

In other words, in an overheated future, a new “cold” war will no longer be restricted to what were once the more temperate parts of the planet.

If, in climate change terms, the military worries about anything globally, it’s increased human migration from devastated areas like today’s flood-ridden Pakistan, and the conflicts that could come with it. In cold bureaucratese, that DNI report predicted that, as ever more of us (or rather, in national security state terms, of them) begin fleeing heat, droughts, floods, and tropical cyclones, “Displaced populations will increasingly demand changes to international refugee law to consider their claims and provide protection as climate migrants or refugees, and affected populations will fight for legal payouts for loss and damages resulting from climate effects.” Translation: We won’t pay climate reparations and we won’t pay to help keep other peoples’ home climates livable, but we’re more than willing to spend as much as it takes to block them from coming here, no matter the resulting humanitarian nightmares.

Is It Finally Time to Defund War?

Along with the harm caused by its outsized greenhouse gas emissions and its exploitation of climate chaos as an excuse for imperialism, the Pentagon wreaks terrible damage by soaking up trillions of dollars in government funds that should have gone to meet all-too-human needs, mitigate climate change, and repair the ecological damage the Pentagon itself has caused in its wars in this century.

Months before Russia invaded Ukraine, ensuring that yet more greenhouse gases would be pumped into our atmosphere, a group of British scholars lamented the Biden administration’s enthusiasm for military funding. They wrote that, “rather than scaling back military spending to pay for urgent climate-related spending, initial budget requests for military appropriations are actually increasing even as some U.S. foreign adventures are supposedly coming to a close.” It’s pointless, they suggested, “to tinker around the edges of the U.S. war machine’s environmental impact.” The funds spent “procuring and distributing fuel across the U.S. empire could instead be spent as a peace dividend [that] includes significant technology transfer and no-strings-attached funding for adaptation and clean energy to those countries most vulnerable to climate change.”

Washington could still easily afford that “peace dividend,” were it to begin cutting back on its military spending. And don’t forget that, at past climate summits, the rich nations of this planet pledged to send $100 billion annually to the poorest ones so that they could develop their renewable energy capacity, while preparing for and adapting to climate change. All too predictably, the deep-pocketed nations, including the U.S., have stonewalled on that pledge. And of course, as the recent unprecedented monsoon flooding of one-third of Pakistan — a country responsible for less than 1% of historic global greenhouse gases — suggests, it’s already remarkably late for that skimpy promise of a single hundred billion dollars; hundreds of billions per year are now needed. Mind you, Congress could easily divert enough from the Pentagon’s annual budget alone to cover its part of the global climate-reparations tab. And that should be only the start of a wholesale shift toward peacetime spending. No such luck, of course.

As the National Priorities Project (NPP) has pointed out, increases in national security funding alone in 2022 could have gone a long way toward supporting Joe Biden’s expansive Build Back Better bill, which failed in Congress that year. That illustrates yet again how, as William Hartung put it, “almost anything the government wants to do other than preparing for or waging war involves a scramble for funding, while the Department of Defense gets virtually unlimited financial support,” often, in fact, more than it even asks for.

The Democrats’ bill, which would have provided solid funding for renewable energy development, child care, health care, and help for economically stressed families was voted down in the Senate by all 50 Republicans and one Democrat (yes, that guy) who claimed that the country couldn’t afford the bill’s $170 billion-per-year price tag. However, in the six months that followed, as the NPP notes, Congress pushed through increases in military funding that added up to $143 billion — almost as much as Build Back Better would have cost per year!

As Pentagon experts Hartung and Julia Gledhill commented recently, Congress is always pulling such stunts, sending more money to the Defense Department than it even requested. Imagine how much crucial federal action on all kinds of issues could be funded if Congress began deeply cutting, rather than inflating, the cash it shovels out for war and imperialism.

Needed: A Merger of Movements

Various versions of America’s antiwar movement have been trying to confront this country’s militarism since the days of the Vietnam War with minimal success. After all, Pentagon budgets, adjusted for inflation, are as high as ever. And, not coincidentally, greenhouse gas emissions from both the military and this society as a whole remain humongous. All these years later, the question remains: Can anything be done to impede this country’s money-devouring, carbon-spewing military juggernaut?

For the past twenty years, CODEPINK, a women-led grassroots organization, has been one of the few national groups deeply involved in both the antiwar and climate movements. Jodie Evans, one of its cofounders, told me recently that she sees a need for “a whole new movement intersecting the antiwar movement with the climate movement.” In pursuit of that very goal, she said, CODEPINK has organized a project called Cut the Pentagon. Here’s how she describes it: “It’s a coalition of groups serving issues of people’s needs and the planet’s needs and the anti-war movement, because all of us have an interest in cutting the war machine. We launched it on September 12th last year, after 20 years of a ‘War on Terror’ that took $21 trillion of our tax money, to destroy the planet, to destroy the Middle East, to destroy our communities, to turn peacekeeping police into warmongering police.” Cut the Pentagon, says Evans, has “been doing actions in [Washington] D.C. pretty much nonstop since we launched it.”

Sadly, in 2022, both the climate and antiwar struggles face the longest of odds, going up against this country’s most formidable strongholds of wealth and power. But CODEPINK is legendary for finding creative ways of getting in the face of the powerful interests it opposes and nonviolently upending business-as-usual. “As an activist for the last 50 some-odd years,” Evans says, “I always felt my job was to make power uncomfortable, and to disrupt it.” But since the start of the Covid pandemic, she adds, “Power is making us more uncomfortable than we are making it. It’s stronger and more weaponized than it has been before in my lifetime.”

Among the hazards of this situation, she adds, social movements that manage to grow and become effective often find themselves coopted and, she adds, over the past two decades, “Too many of us got lazy… We thought ‘clicktivism’ creates change, but it doesn’t.” Regarding an education bill early in the Trump administration, “We had 200 million messages going into Congress from a vast coalition, and we lost. Then a month later, we had only 2,000 people, but we were right there in the halls of Congress and we saved Obamacare. Members of Congress don’t like being uncomfortable.”

As the military-industrial complex and Earth-killing capitalism only seem to grow ever mightier, Evans and CODEPINK continue pushing for action in Washington. And recently, she believes, a window has been opening:

For the first time since the sixties and early seventies, it feels like a lot of people are seeing through the propaganda, really being willing to create new structures and new forms. We need to go where both our votes and our voices matter. Creating local change — that’s our work. Our divest-from-war campaigns are all local. Folks who care about the planet need to figure out how do we make power uncomfortable… It’s not a fight of words. It’s a fight of being.

The major crises we now face are so deeply entangled that perhaps grassroots efforts to face them might, in the end, coalesce. The question remains: From the neighborhood to the nation, could movements for climate mitigation and justice, Indigenous sovereignty, Black lives, economic democracy, and, crucially, an end to the American form of militarism merge into a single collective wave? Our future may depend on it.

President’s warning follows Beijing’s military exercises after House Speaker Pelosi visited Taipei

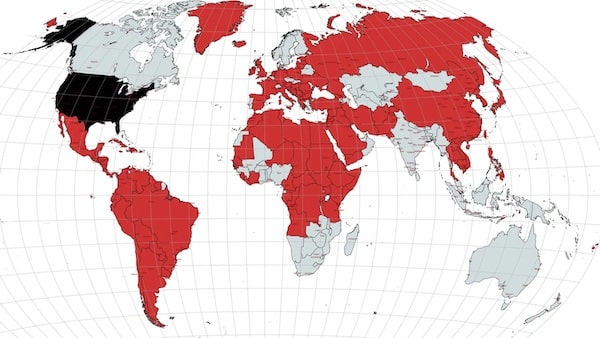

The U.S. military launched 469 foreign interventions since 1798, including 251 since the end of the first cold war in 1991, according to official Congressional Research Service data.