Archive for category: #Labor #union #strike

Here’s What’s in the New Bill Jointly Backed by Uber and the Teamsters in Washington State

Stephanie

Mon, 02/28/2022 – 10:28

Unions and Worker Co-ops: Why Economic Justice Requires Collaboration

Stephanie

Mon, 02/14/2022 – 16:14

What is the point of socialists organizing inside unions? For reformists seeking the electoral road to socialism, it’s about gaining union members’ votes, and possibly using strikes to advance and defend pro-working class reform programs. Independent rank and file organization might move unions to the left and line them up behind reform socialist strategy, but so might bureaucratic leadership.

For revolutionaries, unions are schools for struggle where our class learns to take power directly into our own hands. But union leadership structures disrupt this process. Recognizing this, practitioners of rank and file oriented strategies prioritize independent organization from below over running for leadership. Moreover they view union officeholding and staff jobs skeptically as means to advance class emancipation and power. As a result we are accused from the left of having no “end-game,” or from the right of a dead-end purism that refuses the responsibilities of power.

In 2000 Kim Moody’s The Rank and File Strategy partially answered this type of criticism: Rank and file organization aims to build transitional organizations that lay the basis for industrial as well as political working class power on an independent basis. But without the next step beyond this—socialist revolution—unions remain subject to conservatizing bureaucracy, and working-class parties, therefore, to overwhelming pressure from the capitalist system.

The low ebb of class struggle by 2000 meant Moody arguably went as far as he credibly could at the time. But with a new, increasingly labor-focused generation of socialists, and exciting new developments in the union movement, today we might venture to clarify the “end game” of this revolutionary approach to union work.

For this we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Almost forgotten today, in the 1910s a group of syndicalist and Marxist workers centered in the U.K.’s stormy class struggles formulated their own rank and file strategy as a direct path to workers’ councils and revolution.

Britain, the first industrialized country, also had the world’s oldest unions. The world’s first nationwide workers’ movement developed there with the radical Chartist movement, which peaked in the 1840s. Marxism itself emerged only after British workers demonstrated their class potential in this way.

In the following decades, the labor movement showed flashes of militancy and insurgency but eventually became institutionalized because of exclusionary craft unionism and support for the pro-capitalist Liberal Party. In the 1860s, Karl Marx mobilized Manchester textile workers to support slave emancipation and oppose British intervention on the side of the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War. British unions led in the founding of the First International. And in 1888, unorganized industrial workers, led by women, launched an insurgent strike wave. Yet by the turn of the century, British unions shared with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) a uniquely conservative craftism and non-socialist ideology. What’s more, they were older and better established than the AFL, representing 14.5 percent of workers, compared to 5 percent for the AFL. Elsewhere, Marxists and labor anarchists set themselves up for lasting influence in union movements they helped found around this time. But in Britain (as in the U.S.), revolutionaries faced the challenge of pre-existing federations more or less hostile to their strategies and ideas.

Almost forgotten today, in the 1910s a group of syndicalist and Marxist workers centered in the U.K.’s stormy class struggles formulated their own rank and file strategy as a direct path to workers’ councils and revolution.

A “Great Labor Unrest” spread across the U.K. in the 1910s. Skilled workers resisted technological “dilution” of their jobs. Beginning in 1914, the Great War added fuel to the fire, as inflation savaged workers’ living standards, labor shortages increased their bargaining power, and the war radicalized the militants. British union membership went from 2.5 to 8.3 million in the decade. But the strike wave also tapped a mood of rank and file rebellion against union officials, who usually stood in the way of militant action. The officials faced (again, as in the U.S.) a barrage of wildcat strikes.

British syndicalists and Marxists refined their strategy successively through this decade. In 1910, veteran worker militant Tom Mann visited the world’s largest syndicalist confederation, the French Confederation Generale du Travail (CGT). At the urging of the CGT, he returned to Britain the following year determined to convince the militants to ditch their “dual unionism”—the creation of radical unions to compete with existing unions—and instead to “bore from within” the established unions. He formed the Industrial Syndicalist Education League (ISEL) for the purpose. (The great U.S. revolutionary unionist William Z. Foster, soon after, self-consciously followed almost exactly in Mann’s footsteps.)

In 1911, Mann and ISEL members led Liverpool’s transport workers in a gigantic strike that saw the strike committee become the city’s de facto governing authority, much as happened during the Seattle General Strike of 1919.

ISEL members campaigned for craft unions to merge (“amalgamate”) into industrial organizations capable of united strikes against modern industrial factory firms. In 1910, the National Transport Workers’ Federation resulted, followed by the National Union of Railwaymen in 1913, and the “Triple Alliance” of these two plus the miners in 1914.

ISEL assumed that the “militant minority”, through leadership in strikes and amalgamations, could displace conservative bureaucrats, take union leadership, and convert unions into revolutionary bodies. ISEL never got the chance to try, as it fell apart in 1913. But in coal-mining Wales, syndicalists frustrated by the failures of this very approach tried something new.

The Unofficial Reform Committee (URC) formed around 1912 inside the miners’ union. The URC advocated not taking over official leadership, but rank and file pressure on leaders to prevent their repeated pattern of sell-outs, often despite militant pasts and promises. Short-term, they would act as a “ginger group,” pushing the officials to militancy. Long-term, they aimed to re-write the Union’s constitution to replace paid-staff bureaucracy with on-the-job miners holding official leadership. The URC fought successfully and reorganized the miners’ union along these lines.

Yet the problems remained. In the light of similar experiences in the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), which organized skilled workers in engineering plants in Glasgow and Sheffield, J.T. Murphy of the Socialist Labor Party (SLP) argued that the tendency of unions to restrain militancy went deeper than the personal failings of leaders (as ISEL had seen it), and deeper even than the democratic defects of union constitutions (as per the URC). The problem was the inherent role of unions as negotiators with employers. For the rank and filer, “the conditions under which he labors are primary; his union constitution (designed for negotiation not confrontation) is secondary.” But once holding a union office, “those things that were once primary are now secondary.” Negotiation instead of struggle had unfailingly shaped the psychology of even insurgent leaders, as well as the machinery of the organizations. Murphy also pointed out that amalgamation had hardly produced militant unionism. Amalgamationists “sought for a fusion of officialdom as a means to the fusion of the rank and file. We propose to reverse this procedure.”

Murphy’s 150,000-selling pamphlet The Workers’ Committee, like the URC, advocated independent rank and file organization. In this, Murphy and his comrades broke with the SLP’s dual unionism in favor of boring from within. But unlike the URC, they aimed not at pressuring leaders, but to “take on direct responsibility for the conduct of the fight against the bosses and the state”.

Liverpool Transport Strike of 1911. Source libcom.org.

Liverpool Transport Strike of 1911. Source libcom.org.

Further, their goal was not to reform, but to transcend the unions. The workers’ committee would begin in shop committees. The ASE, by contrast, organized through neighborhood branches as its base units. Murphy argued that shop committees would involve many more workers and naturally facilitate direct action by centering on the shop, where workers came daily as a matter of survival. As he wrote, official union structures are “only indirectly related to the workshops, whereas the Workers’ Committee is directly related.” The shop committees included all workers in their shops despite their separate organization in multiple craft unions—amalgamation from below. Today most unions actually do organize directly at worksites, yet as a rule not for the purpose of militant direct action. So independent rank and file organizations still often need to play the activating role once played by these shop committees.

Shop committees elected a steward for every 15 workers, with stewards collecting “nominal fees” from each member. Shop committees, in Murphy’s vision, link up and delegate leaders to factory committees, industrial committees, regional committees, and a national workers’ committee. Influenced by anarcho-syndicalism, the pamphlet vests final decision-making authority at the local level, with higher steps on the pyramid organizing information and voting at the base. The resultant structure functionally supersedes the national Trade Union Council (TUC). Yet Murphy emphasized “we are not antagonistic to the trade union movement.” Committee participants run for union executive board posts where useful. But they “definitely oppose any member taking any office in a trade union that will take him away from the shop or his tools.” The committee movement grows directly out of the unions, which form its basic media.

The scheme was no pipe dream. Workers’ committees on this model developed out of massive wartime struggles in Glasgow, and in Murphy’s home town of Sheffield. In Glasgow in 1915, 10,000 rank and file ASE members took wildcat action and won a wage increase. After this victory, the strike committee continued on, becoming the Clyde Workers’ Committee (named for the Clyde River). Weekly committee meetings of three hundred shop stewards took place.

Meanwhile, war-driven inflation wrought misery and anger. Rising rents caused a 25,000-strong rent strike in Glasgow in 1915. The Clyde Workers’ Committee threatened to shut down munitions production in solidarity. In response, Parliament passed the War Restrictions Act—the nationwide rent control law still residually in force to this day. In The Western Soviets, Donny Gluckstein points out that the workers’ committees never became full-fledged workers’ councils—soviets—because they did not represent all working-class people regionally but remained primarily engineering industry workers. But when working together, rent strikers and the committee acted like a soviet. It is not hard to see how formalizing this cooperation could have extended the committee into a true workers’ council.

When rank and file groups link up across worksites, agencies, companies, and industries, they can form the skeletons of workers’ councils.

The Clyde Workers’ Committee broke under the arrests of its leaders for anti-war activity in 1916. But J.T. Murphy’s Sheffield Committee continued on. It led an anti-conscription strike of 200,000 workers in 48 towns in 1917. The Shop Stewards’ Movement, an embryonic national workers’ committee like that envisioned in Murphy’s pamphlet, formed out of that strike. It brought together factory delegates from many of the striking towns. After the Russian Revolution, the Shop Stewards’ Movement joined the Hands Off Russia campaign and stopped the U.K.’s SS Jolly George from sailing to Poland to deliver arms to the counter-revolution.

The Shop Stewards’ Movement affiliated to the newly formed Communist International (Comintern) in 1920. The Comintern was initiated by the Russian revolutionaries in power to develop Communist Parties around the world as the key step toward world revolution. By 1921, Mann, Murphy, and most of the leaders of the Shop Stewards’ Movement joined the newly-formed British Communist Party. As delegates to the Comintern and its allied trade union confederation, the Red International of Labor Unions (RILU), they buttressed the Comintern’s “united front” strategy by supporting boring from within existing unions. But they also pushed back on contradictory and sectarian union strategies coming from the Bolsheviks. The Russian soviets had not developed out of unions. Pre-Revolutionary Russian unions were usually illegal, short-lived, and led by Marxists. Thus the Bolsheviks had had no experience taking on pro-capitalist union bureaucracy—a central challenge for revolutionaries in much of the world today.

So, in response to the Second Comintern Congress’ slogan “conquer the unions,” veteran U.K. workers’ leader and Communist Willie Gallacher replied that winning high union office had “corrupted our own comrades…We have often made our comrades into big trade union officials, but we have seen that nothing can be achieved for communism and the revolution through such work.”

Confusingly, RILU’s very existence suggested that Communists had to pursue dual unionism, at least in the international sphere where RILU sought to break in against the existing international union bodies. Yet Murphy, who helped draft RILU’s founding manifesto, later claimed the British trade unions would not have countenanced any suggestion of splitting. The Brits also influenced the inclusion of the shop committee model into the RILU program.

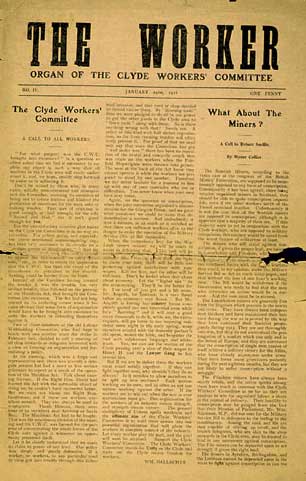

January 1916. The newspaper of the Clyde Workers’ Committee included an article entitled: “Should the workers arm?” This served as a pretext to ban the paper and arrest three SLP leaders, even though the answer had been, “No.”

January 1916. The newspaper of the Clyde Workers’ Committee included an article entitled: “Should the workers arm?” This served as a pretext to ban the paper and arrest three SLP leaders, even though the answer had been, “No.”

Back home they formed a boring-from-within group, the National Minority Movement (NMM), and this (like Foster’s Trade Union Educational League in the U.S.) became the U.K.’s RILU affiliate. This avoided any divisive fight over the TUC’s international affiliation. The NMM exerted considerable influence in the early 1920s, allowing the comparatively tiny British Communist Party (with about 5,000 members) to punch above its weight in the labor movement.

So, while only partially successful, the British revolutionary unionists influenced early Communism in favor of boring from within, independent rank and file organizing, skepticism toward union office, and direct action through the shop committee system. In other words, the foundations of the rank and file strategy as understood today.

But additionally, the revolutionary implications of the workers’ committees deserve rescue. Regardless of whether official union structures oppose it, union organization facilitates rank and file action. Independent rank and file organizing need not seek to confront union leadership, or even contest for leadership positions. When rank and file groups link up across worksites, agencies, companies, and industries, they can form the skeletons of workers’ councils. This will not be possible or meaningful absent a serious upsurge of struggle. But something like this happened during the Arizona teachers’ strike of 2018. Rank and file union members, on their own initiative and completely independent from their officials, organized a Facebook group consisting of building representatives from two thousand schools statewide. The group formed the real coordinating center of the strike. The politics of social justice unionism, utilized to frame the teachers’ struggle as spearheading a broader community fight pointed, albeit distantly, toward the transition from workers’ committee to workers’ council. (Jason Koslowski of Left Voice, pointing to a similar case from Argentina, counterposes this workers’ committee–type approach to what he terms the “pessimistic” rank and file strategy of Kim Moody, based around opposition union caucuses. I believe the two approaches complement and overlap one another.)

If today’s upsurge of strikes continues, the new generation of socialists in the unions could center their rank and file organizing on direct struggle instead of union elections. (Even so, rank and file election campaigns could spread as well, with all the highly positive potentials represented by the Chicago and LA Teachers’ examples.) As Moody argues, this can lead to transitional organizations moving us toward working-class independence and socialist politics. But it can also lead us to foretastes and embryonic experiences of dual-power organizations—that is, organizations that foreshadow the creation of an alternative authority to the power of the existing capitalist state. The combination of these two dynamics can fertilize the soil for a new mass class consciousness, and for a new revolutionary vision among a militant minority.

In an industry plagued with poverty pay, job insecurity and deceptive recruitment practices, temp workers have scant protections.

#Striketober may be over, but the struggles to organize at Amazon have not been not defeated — in fact, they’re spreading. Three Amazon locations are currently attempting to unionize: two in Staten Island, and one in Bessemer, Alabama.

Ballots went out yesterday to over 6,100 workers at Amazon’s Bessemer warehouse for a mail-in election with a March 25 deadline. You may remember the Bessemer unionization effort from March of 2021. Last year, that effort failed in no small part due to Amazon’s union-busting tactics including anti-union text messages and bribes. While forcing their workers to attend mandatory anti-union lectures, they pressured the city into changing the timing of a traffic light in order to disrupt organizing efforts, and even strong-armed the USPS into installing a mailbox that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) had explicitly barred, in an Amazon-branded ballot-collecting tent. As a result, the NLRB determined that Amazon used union-busting tactics, and ordered a new union vote.

In Staten Island, New York, two Amazon warehouses are now seeking to unionize. JFK8 workers attempted to unionize last year but withdrew their petition in November, only to refile in December. As the NLRB was forced to admit, the workers have enough signatures for a hearing to be held in mid-February. This meeting will decide how many workers are eligible to vote, as well as the timing of the vote.

Within the past week, workers at the Staten Island warehouse LDJ5 submitted petitions to the NLRB to request a union vote. These two New York City warehouses are not unionizing through an existing union, but filing under a new one, called Amazon Labor Union. Among the leaders of the effort is Chris Smalls, who was fired for protesting Amazon’s lack of safety measures at the height of the pandemic.

Amazon is the country’s second-largest private employer after Walmart, and is notorious for its horrendous working conditions. In the words of Francis Wallace, a worker interviewed by Left Voice in Bessemer last year: “It is extremely tiring, I will agree with that. Of course, there’s bending and standing up all the time. There’s a ladder inside my area, ’cause I do stowing. I’m climbing up and down the ladder, bending up and down, picking up the boxes. When you do that for 10 hours straight and you only have three, maybe 15 minute breaks, it gets really tiring.” Another worker reported extremely hot warehouses, without ventilation.

Multiple workers have died on the job at Amazon warehouses over the past year. Six died during a tornado that struck the midwest in December, and two died at the Bessemer location. One worker suffered a stroke after being told by management that he couldn’t leave work. Hours later, another worker died. “There is no shutdown. There is no moment of silence. There is no time to sit and have a prayer,” Perry Connelly explained. “A couple of people that worked directly with him were badly shaken up and wanted to go home and were not allowed to go home.”

These three unionization efforts come on the heels of the important strikes in October and November, popularly known as #Striketober, with stoppages at large employers like Kellogg, John Deere, Columbia University, and hundreds of smaller workplaces. Only a few miles from Bessemer, Alabama miners at Warrior Met Coal have been on strike for nearly ten months. Recently, dozens of Starbucks stores have also filed for union elections. This all comes amidst the so-called “Great Resignation,” with workers quitting their jobs in droves. The pandemic has shifted the spotlight to the working class.

At Amazon, the discontent among the working class is also expressing itself in more direct ways, through mobilization and action. In December, workers at Amazon warehouses in Chicago walked off the job, demanding a wage increase and better working conditions, organized by Amazonians United, a labor network that organizes at Amazon throughout the country.

A success at Amazon may unleash a wave of unionization filings, just as the first successful Starbucks union in Buffalo has inspired similar drives at dozens of other locations.

As expected, Amazon is again engaging in union busting, revealing just how frightened they are of the growing awareness of their workers’ collective power. Anti-union signs, as well as paid union busters, were spotted at the JFK8 warehouse in Staten Island. Managers have held mandatory anti-union meetings. Amazon has brought in union buster David Acosta — a self-described “Union Avoidance Consultant,” who earned over $400,000 in 2017 — who has reportedly illegally threatened workers against voting to unionize. Employee Daequan Smith was illegally fired for trying to unionize. This is nothing new for Amazon, as previous unionization attempts show.

Amazon is hell bent on making sure no union emerges at their workplaces and they are well aware of the domino effect that one union may create. That is why they will throw everything they have at defeating these efforts.

As the first Bessemer Amazon unionization drive showed, to win a union, it is not enough to rely on Democratic Party politicians and celebrity endorsements. Much criticism has been leveled at the RWDSU for their lack of worker participation, from our own pages as well as from authors like Jane Mcalevey. The Staten Island warehouses must also learn from this.

There is no substitute for the rank and file. If these unions have any chance of winning, they must be organized by and for workers. And these unions should not only be for the purpose of winning a union, but to create a fighting force for the working class. And as the Great Resignation highlights, it’s not enough to be unionized; after all teachers and healthcare workers who are struggling under horrendous work conditions are leaving in droves. Workers must reject top down business unionism and organize fighting unions, organized by and for the rank and file — a union is not an end in itself, but a step in building a fighting working class.

Historian Nate Holdren questions the assumptions about why strikes have risen and fallen over the last century.

Everyone is desperate for signs of life in the American working class, so the breathless talk of a “Striketober” a few months back made sense. But new Bureau of Labor Statistics data throws cold water on that idea: there was no strike upsurge.

United Auto Workers picket signs tossed on the ground outside a strike at General Motors, 2019. (Jeff Kowalsky / AFP via Getty Images)

There was a lot of enthusiastic talk about a wave of labor militancy last year — remember “Striketober”? With the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) preliminary data for December out — it will be slightly revised next month, but not by much — we can now look at the full year in historical perspective. It was a quiet year, even by recent standards.

First, the number of “stoppages” involving a thousand workers or more.*

There were about half as many major strikes in 2021 as there were in 2018 (the year of the teachers’ strikes) and 2019 (which included a five-week strike against GM), and nothing compared to the pre-Reagan decades.

Comparing the number of workers involved in strikes to the labor force yields even less impressive results: 0.02% of total employment, a sixteenth as much as in 2018 and less than a hundredth the average of the 1950s. Even the 1990s, hardly a decade known for class struggle, saw eleven times the share of the workforce walking out.

Yet another view: what the BLS calls, with a touch of moralism, “days of idleness” expressed as a percent of total hours worked. Again, the line is almost indistinguishable from the x-axis, so close it is to 0–0.002%, to be precise.

Here’s a closeup of the idleness measure since 2000 using monthly data. That blip on the right is what was called “Striketober,” even by bourgeois outlets like NPR. Hours of “idleness” during October 2021 were a quarter as many as in October 2019, the month of the strike against General Motors.

I’d love nothing more than a strike wave and an upsurge of militancy. It’s just not here yet.

*Two data notes: First, the BLS combines strikes and employer lockouts into stoppages because exact causes can be hard to tell apart. And second, whenever I write these up, people say there are lots of smaller strikes that fall under the thousand-worker limit. There aren’t really. The Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) used to publish data on smaller strikes, in an extremely user-unfriendly form. I wrote about that data in 2018 and they followed the same pattern as the larger strikes. The FMCS stopped updating the data in the early Trump years and the historical data has disappeared from their website.

After spending most of 2021 on the picket line, nurses at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts, are returning to work. Their strike holds two lessons: health care corporations will erode standards infinitely for profit, and worker solidarity is the only way to stop them.

Saint Vincent hospital nurses on strike in Worcester, Massachusetts. (Massachusetts Nurses Association)

After most of a year on the picket line, the nearly seven hundred nurses who struck at Saint Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts, are preparing to return to work. This concludes the longest strike in the United States in 2021 and the longest nurses’ strike in Massachusetts history. According to the nurses’ union, the Massachusetts Nurses Association (MNA), it was also the longest nurses’ strike the United States has seen in more than fifteen years.

On December 17, 2021, the nurses reached a tentative contract agreement with the hospital and its for-profit owner, Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare. On Monday, they voted overwhelmingly to ratify the new contract, which locks in staffing improvements to ensure patients receive better care.

The lessons we can draw from this strike are twofold. First, health care corporations like Tenet will go to every length imaginable to avoid subtracting from their profits to raise standards of care. And second, worker solidarity is the only reliable way to check these corporations’ power.

Unsafe Staffing Levels

Saint Vincent nurses walked out on March 8, 2021, after trying for eighteen months to force their employer to fix serious safety problems at the hospital. Chief among their concerns was a pattern of chronic understaffing that the nurses say endangered patients.

One of the nation’s largest health care systems, Tenet Healthcare has raked in record profits during the pandemic while implementing bare-bones staffing and other cost-cutting measures at its facilities, with results Tenet workers say have been appalling.

The relationship between nurse staffing levels and patient care outcomes is well documented, with research suggesting that the chances of in-patient death jump 7 percent with each additional patient a nurse is assigned to care for.

Back in 2018, the MNA fought for Massachusetts to follow the example set by California, the only state with legally defined nurse-to-patient ratios. California’s nurse staffing law has improved care outcomes, particularly for poor patients. In Massachusetts, the hospital lobby managed to reverse initial public support for the 2018 ballot measure by launching an aggressive campaign to confuse voters that eventually defeated the measure.

After trying and failing to create change through the ballot box and various shop-floor strategies, the MNA nurses hit the picket lines to protest understaffing at Saint Vincent Hospital.

An Arduous Battle

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the hospital and its parent company tried to crush the strike. They unsuccessfully sought to malign the nurses in the eyes of the Worcester public, taking out full-page anti-strike ads in the local paper. They paid Worcester police hefty sums to function as Saint Vincent’s security apparatus. They reduced the hospital’s operations amid a COVID-19 surge, evidently in order to convince the Massachusetts Department of Unemployment Assistance that the striking nurses no longer deserved benefits. And for months, they insisted that scabs would replace strikers in high-stakes roles attained through long years of specialized experience.

Steve Striffler, an anthropologist who directs the Labor Resource Center at the University of Massachusetts Boston, told Jacobin that Tenet’s behavior appears designed to convey

that nurses everywhere should think long and hard about striking because companies are going to spend tens of millions of dollars and fight to the end . . . to resist improved wages/conditions, resist improved hospital safety, and to bust unions. [Tenet] didn’t succeed, but they came close and sent a clear message to unions that they are willing to fight hard.

The MNA nurses viewed themselves as the last line of defense for patients against the company’s campaign to erode care. In the end, their collective action forced Tenet to boost staffing and abandon its insistence on displacing strikers from their previously held positions and shifts.

Better Staffing

The nurses’ new contract, ironed out at an in-person mediation session with US secretary of labor Marty Walsh, guarantees specific staffing improvements. These include reduced patient assignments on the cardiac postsurgical unit, the two cardiac telemetry floors, and the behavioral health unit. The contract also limits the hospital’s ability to “flex” nurses, or send them home mid-shift when management deems them superfluous.

While these new policies fall short of the MNA’s original demands, the contract stipulates that all nurses will be recalled to their previous positions and shifts within thirty days. This back-to-work guarantee — standard fare for strike resolutions — resolves the final sticking point in the nurses’ negotiations with Tenet (which has a history of retaliating against employees who call out unsafe care conditions)

Johnnie Kallas, who researches health care labor organizing and directs the Labor Action Tracker at Cornell’s Industrial and Labor Relations School, told Jacobin:

The nurses’ victory is a huge win for the labor movement because they achieved considerable improvement in their working conditions while facing enormous obstacles. . . . Despite the threat of permanent replacements, MNA nurses won a strong contract that improved staffing in the middle of a global pandemic while maintaining their previous jobs.

A New Attack on Union Power

The MNA nurses voted 487 to 9 in favor of ratification. But without universal, nonprofit health care, for-profit providers will continue to “maximize their cash positions” by trampling over the needs of patients and workers.

Tenet remained indifferent to the pleas and indictments from high-profile elected officials, suggesting that legislators are constrained in their ability to manage health care corporations’ greed. To push back on abusive employers and transform the industry, health sector employees will need to continue gumming up the works of for-profit care by organizing. Wherever they do, they should be ready for pushback.

Just three days after the Saint Vincent nurses reached the tentative agreement with their employer, one of the permanently hired scab nurses filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board in an attempt to decertify the MNA as the union for nurses at the hospital. As local investigative journalist Bill Shaner has reported, the nurse purportedly spearheading the decertification petition is represented pro bono by lawyers from the anti-union National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation.

Still, when asked for her thoughts on the campaign to remove the MNA, Saint Vincent nurse and bargaining unit co-chair Marlena Pellegrino brushed the decertification effort off. “We are solely focused on our path ahead. We have been battle tested.”