Midterm wins bought organizing time for pro-democracy forces, but MAGA authoritarianism still menaces US politics. In “Pro-democracy Organizing Against Autocracy in the United States,” scholar/activists Erica Chenoweth and Zoe Marks map the threat and steps that could help defeat it. Convergence interviewed the two and will be publishing reflections and responses to the report. Bill Fletcher Jr.

Archive for category: #Labor #union #strike

Union-Busting Firms Are Teaching Corporations to Cynically Co-Opt Progressive Rhetoric As They Crush Worker Organizing

Greg

Tue, 02/07/2023 – 17:51

American unions’ members are down, but their finances are through the roof. The labor movement can’t rebuild its dismally low membership unless unions start spending their resources on aggressive new organizing campaigns.

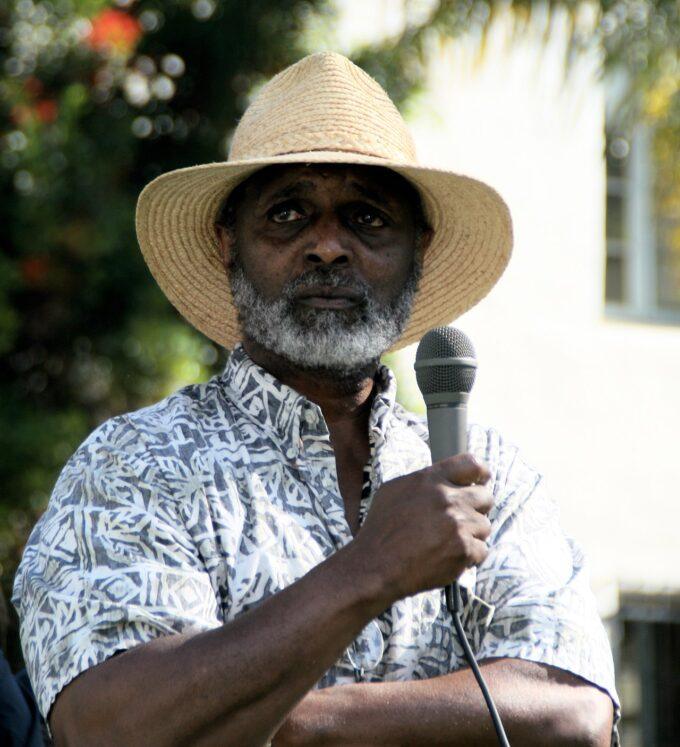

Rory Gamble, former president of United Auto Workers, speaks during the Ford Motor Co. centennial celebration of the Rouge manufacturing complex in Dearborn, Michigan, on September 27, 2018. (Sean Proctor / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The Department of Labor recently released its annual report on union membership, which means it’s time to commence the annual rite of examining the numbers. This year’s report showed an increase of 273,000 members from 2021 to 2022, but a decline in union density (the percentage of all workers who are union members) from 10.3 percent to 10.1 percent of total US employment. In historical perspective, the last time union density hovered as low as 10 percent was the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929. The high point of union density was in the 1950s, when approximately a third of all workers were members of a union.

Every year, union activists and reporters analyze the Department of Labor membership data looking for signs of labor’s decline or resurgence. We should parse those numbers. But parsing the financial practices of unions may tell a more complete story about the direction labor is headed.

The strange paradox is that while union membership and density have steadily declined, the financial balance sheet of organized labor has ballooned, according to the latest available data from the Department of Labor. As illustrated in the chart below, since 2000, labor’s net assets (assets minus debt) rose from $11 billion in 2000 to $32 billion in 2021, a 191 percent increase. Over that same period, union membership declined by 2.3 million members, a 14 percent decline. (Financial data for 2022 is not yet available.) A full report on union finances and the methodology is available here.

How is it possible to grow union assets while losing millions of members? First, membership dues are typically tied to a percentage of wages, so as union wages rise, membership dues do too, softening the financial impact of declining membership. Union median wages are up 75 percent since 2000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Second, labor generates significant investment and rental income from its growing balance sheet, including investments in the stock market (and even private equity and hedge funds).

And third, labor spends less money on activities like organizing and strikes than it brings in from dues and investment revenue, running annual budget surpluses that boost assets. Slow declines in union membership, perversely, lead to annual budget surpluses and the growth of financial assets.

What’s happening here is that business unionism, the pejorative term for unions that narrowly focus on improving wages and benefits for existing unionized workers rather than advancing an agenda that benefits the entire working class, has graduated to what I call “finance unionism,” where the accumulation of financial assets from the existing membership is the primary route to growth, rather than the mass organizing of new workers into unions.

Finance Unionism’s Built-In Defeatism

Although labor’s $32 billion in net assets is larger than most US foundations, the Department of Labor financial data actually understates the true value of labor’s assets, because unions are only required to report the cost of their investments rather than the market value. This divergence was vividly illustrated at the United Auto Workers (UAW) 2022 constitutional convention, where delegates debated the feasibility of increasing strike pay from $400 a week to $500 a week, a particularly important debate given the upcoming contract negotiations at the Big Three automakers.

The strike pay resolution was ultimately defeated after delegates, relying on financial statements provided by the union, concluded that increased strike benefits might be financially unsustainable. Yet an investigative report by the Intercept found that delegates were provided with misleading financial information at the convention.

While delegates were told union assets were valued at $960 million (at cost), the market value of the union’s assets was around $1.4 billion, about $424 million higher. If delegates were aware of the true value of the UAW’s assets, the resolution on strike pay may have met a better fate. Nevertheless, the UAW example suggests total union assets are far higher than the $32 billion number if assets were reported at market value.

In responses to the Department of Labor report on union membership, the AFL-CIO (a federation of most US labor unions) called for “elected leaders to fix what’s broken by reforming our outdated labor laws that for far too long have stacked the deck against working people.” Undoubtedly, labor law is fundamentally broken, as the rampant illegal anti-union activities at Starbucks and Amazon clearly illustrate. But few believe that the PRO Act, the most recent proposed labor law reform package, has a credible chance of passage anytime soon, stymied by the Senate filibuster and “moderate” Democrats.

The worry is that organized labor will draw the same lesson they drew from the defeat of labor law reform legislation in 2009: organizing on a large scale is impossible without new labor legislation, and unions should hold back until the political climate changes. Finance unionism is a powerful economic inducement to remain on this defeatist track.

The problem is that if unions don’t dramatically expand organizing, particularly in the Midwest and South, it is hard to see how the political dynamic changes in a way conducive to passing federal labor legislation. Since 2010, unions have tried to change the dynamic by spending (at the minimum) over $8 billion on politics. But the real source of labor’s political power will come from mobilizing new union workers, particularly in red and purple states with low union density.

“All In”?

The AFL-CIO says it isn’t just waiting for labor law reform, asserting that “[t]his year, the labor movement is going ‘all in’ on an organizing agenda that will ensure every worker who wants a union has the chance to join or form one.” That agenda consists of creating a new organizing department called the Center for Transformational Organizing (CTO) with a goal of organizing one million new workers over the next ten years. The AFL-CIO executive board approved a per-capita increase (the amount member unions pay to the federation) to raise $10.8 million to fund the CTO.

While proposing any plan is a step forward, the goal of one million members over the next decade will not move the union density needle. The US economy is expected to add 8.3 million jobs over the same time period, and one million new union members will keep union density at or around the current 10 percent level. And while new spending on organizing by the AFL-CIO is welcome, the total spending by the AFL-CIO is miniscule (0.7 percent) compared to the spending by union headquarters and their local affiliates. The vast majority of assets and organizers are located at the affiliate and local level, and only through a change at that level will any program make a meaningful impact.

This point was well understood by John Sweeney, who led the AFL-CIO from 1995 to 2009 after winning the first contested election for the leadership of the federation. (I worked at the AFL-CIO from 1997 to 2000.) Running on an aggressive organizing platform, Sweeney and his supporters set a goal of organizing one million members a year. More importantly, Sweeney publicly called on all unions to devote 30 percent of their budgets to organizing new members.

In some respects, the 30 percent goal was low in comparison to spending during the heyday of union organizing in the 1930s, when the AFL spent 50 percent of its budget on organizing and the CIO spent substantially higher, according to one labor scholar. (The AFL and CIO merged in 1955.) Yet Sweeney’s 30 percent goal was quietly shelved after most unions refused to adopt the budget targets, eventually driving a group of frustrated unions led by SEIU to create the rival labor federation Change to Win in 2005 (currently down from eight affiliate unions to three).

Just spending more dollars on organizing isn’t a surefire recipe for success, but it certainly is a key ingredient to any program to reverse union membership decline on a large scale, and complementary to efforts by workers to organize independent unions like the Amazon Labor Union. Most unions do not publicly disclose the amount they spend on organizing, and unions successfully rolled back a proposed rule by the Department of Labor to require additional reporting on organizing expenditures.

Yet for the few unions that do disclose their budgets, the data are dispiriting. The two key unions that propelled organizing in the 1930s, the steelworkers’ union and UAW, devote very little resources to organizing today. In 2020, UAW allocated 6 percent of its budget to organizing, while today’s United Steelworkers earmarked 3 percent of dues. The Teamsters spent 13 percent of their budget on organizing in 2021, although that will hopefully increase under the new reform leadership. On the encouraging side, SEIU requires in its constitution that locals spend a minimum of 20 percent on organizing.

Yet until the bulk of the labor movement is “all in” on devoting meaningful resources to organizing, it’s hard to see a realistic path to meaningful growth.

1.5 Million Union Members on Strike in 2023?

Of course, the real source of labor’s power isn’t located in its balance sheet or financial resources. Power ultimately lies in collective action by workers withholding their labor to disrupt production through strikes and other activities. In 2023, approximately 150 union contracts will expire, covering 1.5 million workers, or over 10 percent of total union membership. New reform leadership at the Teamsters and UAW (if Shawn Fain wins the election currently underway), representing nearly half a million workers at UPS and the Big Three automakers respectively, are signaling an aggressive and militant bargaining stance.

Their aim is not only to roll back decades of concessionary contracts, but to use strong collective bargaining contracts as a springboard to organize nonunion workers at Amazon and the auto industry. Successful strikes that demonstrate the power of collective action could serve as a powerful object lesson for all workers that they can organize and win against some of the largest companies in the world.

And, the silver lining of finance unionism is that there are billions in financial resources to support courageous workers who make the difficult decision to strike. Over the last decade, labor was unwilling to use its large balance sheet to support strikes, spending less than 3 percent of its net assets on strike benefits. Perhaps 2023 will signal a new era.

Every year, trade unionists examine the annual Department of Labor report on union membership looking for hopeful signs of a resurgence. But the metrics of finance unionism may be a better indicator of change. When we begin to see labor’s net assets decline rather than grow, when surpluses turn to deficits, it may signal that unions are finally spending more on organizing, aggressively engaging in strikes, and employing militant civil disobedience activities that provoke fines and penalties from the government and courts.

Or on a less optimistic note, the decline of union assets will mark the day that the decades of complacency and membership decline have finally come home to roost. Here’s hoping for the former.

Compassionate Eye Foundation/Martin Barraud/OJO Images Ltd / Getty Images

- The US economy isn’t in a recession yet.

- But the tech, housing, and manufacturing industries might be already.

- The more industries that falter, the greater the odds the whole economy falls with them.

No, the US economy isn’t in a recession yet. But some of its key industries might be, suggesting the desired “soft landing” is far from a sure thing.

Bloomberg economist Anna Wong, for instance, recently put the chances of a US recession this year at 80%. But as more industries fall into downturns of their own, she said it could become increasingly difficult for the US economy to avoid the same fate.

“We have a manufacturing recession, a housing recession, a tech recession,” she said in a Bloomberg post last week. “Things are starting to add up.”

It’s possible, however, that the US simply experiences a “rolling recession,” Loyola Marymount University finance professor Sung Won Sohn told CNBC. In this scenario, parts of the economy would “take turns suffering rather than simultaneously” — and the broader economy would never reach recession status.

Recent GDP and retail sales figures point to a slowing but still-growing economy, and economists say the US could enter a recession in 2023. That said, the labor market is still shockingly good, with the US adding a surprisingly large 517,000 jobs in January and seeing the lowest unemployment rate since 1969. Jobless claims figures over the past month remain low despite layoffs in Big Tech.

If the US economy does ultimately fall into a recession, it will partially be because the following three industries dragged it down with them.

The Fed’s efforts to cool rising prices may have doomed housing

Ever since the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to combat inflation, experts knew it could be bad news for the housing industry. Rising rates have led to elevated mortgage rates which, in combination with already-high home prices, have dampened demand.

As early as last September, ING’s chief economist James Knightley told Insider the US housing market had entered a recession.

“We have only had one monthly fall in house prices but with more supply coming on the market at a time when demand is weakening rapidly implies that prices fall further,” Knightley said at the time, adding that home affordability was “stretched to the limit.”

Five months later, things haven’t improved much.

“The housing market is already in recession,” Fannie Mae’s Deputy Chief Economist Mark Palim told Insider, pointing to the “pretty dramatic declines” in home sales in recent months. Fannie Mae is projecting a roughly 7% decline in home prices over the next 24 months.

Home applications have risen in recent weeks as mortgage rates have fallen slightly, but Mortgage Bankers Association economist Joel Kan told Insider that homebuying activity “remains tepid.”

Americans cutting back spending is bad news for manufacturing companies

US consumers facing inflation and dwindling savings are spending less on goods. That’s bad news for the manufacturing industry.

On Wednesday, Reuters markets analyst John Kemp said in a column that US manufacturers “probably entered a recession” in the fourth quarter of last year, based on the new results of the monthly Institute for Supply Management Report. The index, a survey-based measure of activity across the sector, fell to its lowest level since March and April of 2020, and excluding these months, the lowest level since the Great Recession in June of 2009. In December, PMI, another indicator of manufacturing activity, fell to its lowest level since May of 2020.

While the manufacturing industry has avoided widespread layoffs thus far, Kemp attributed this in part to “labor hoarding,” or a hesitancy from business to let workers go after having a difficult time attracting labor over the prior year.

The industry hasn’t been entirely unscathed by layoffs either. 3M, for instance, recently announced it was cutting 2,500 manufacturing roles across the globe.

Tech companies have led the way with layoffs

If any area of the economy is going through some challenges, it’s the tech industry.

In 2022, tech companies like Meta and Twitter laid off roughly 150,000 workers across the globe. While this fell far short of the two million workers let go during the dotcom bubble of 2001, it was well above the roughly 65,000 workers laid off in the sector during the worst years of the Great Recession.

Layoffs have come full speed ahead so far in 2023. There were over 55,000 reported tech layoffs during the first 20 days of January, more than the entire first half of 2022.

The industry’s struggles have been driven by a myriad of factors, including rising interest rates and slowing advertising demand. It’s led some to declare that a “tech recession” is already upon us.

The layoffs, in particular, however, can partially be attributed to companies scaling up their workforces too quickly.

When the pandemic took hold, and Americans flocked to streaming entertainment, at-home fitness, food delivery, and ecommerce, many companies thought this shift would be a permanent acceleration — and hired in mass as a result. But today, businesses in these industries are reckoning with the possibility they got a bit ahead of their skis.

It’s why despite significant job cuts, companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet still have significantly more workers than they did a few years ago.

On Wednesday, over half a million workers in the UK took part in a “mega strike,” the largest labor protest in the country in over a decade. Around 85 percent of schools were affected or fully closed, most trains stood still, and offices stood empty as workers took to the streets to protest the Conservative government of Rishi Sunak and demand higher wages.

Wednesday’s strike was part of a joint call by different unions grouped in the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to demand wage increases in the face of a 14-percent increase in the cost of living. Inflation in January hit 8 percent, with food increasing by between 13 and 15 percent. Around five percent of British households are reportedly running out of food and struggling to afford to buy more, and a growing number of working families are depending on food banks.

Wednesday’s actions were also a protest against the Conservative Party’s attacks on the right to strike. Workers are calling for the repeal of a recent bill which would mandate minimum levels of service during strike actions such as walkouts, forcing employees in certain sectors to keep working. With this , the struggle is not just directed toward achieving a single economic demand, but takes on a more political character, confronting the anti-worker policies of the UK government; this raises the possibility of the fight expanding beyond the half a million workers who have already taken to the streets.

Among the sectors that went on strike were railroad workers, train drivers belonging to the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF) and Rail, Maritime, and Transport Workers (RMT) unions, and teachers belonging to the National Education Union (NEU). 70,000 teachers, librarians, and research workers from 150 universities who are part of the University and College Union (UCU) also joined the demonstration, and are poised to continue striking in 17 more days of action during February and March over pay and pension disputes.

Footage captured thousands of teachers marching through London’s Oxford Circus on what has been dubbed “Walkout Wednesday.” The strike included up to half a million civil servants, and resulted in the partial or full closure of an estimated one half of UK schools. pic.twitter.com/HsqZP8PJpO

— CBS News (@CBSNews) February 2, 2023

Wednesday’s “mega strike” comes after several months of strikes by various sectors. During what some called a “summer of discontent,” RMT workers brought British transportation to a standstill. The UCU likewise held labor actions last year, and in December, nurses held their first national strikes in the more than 100-year history of their union.

Support for strikes in these sectors is mixed, though more people support than oppose the actions. At least 53 percent of people support nurses going on strike, while 49 percent support teachers’ strike actions. Overall, only 37 percent of Britons support unions; however, this proportion is up from 34 percent in November.

The Conservative government of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak continues to play hardball in negotiations, insisting there is no money to grant the demanded salary increases. In the healthcare sector, for example, the government has refused to bump up its offer of an increase between 4.5 and 5 percent, despite soaring inflation. The railway sector has been offered a 9-percent wage increase over two years, a proposal which has been rejected by the workers. The Sunak government is also pushing ahead with its anti-labor minimum service bill.

Union leaderships are so far refusing to call for a joint actions to go on indefinite strike until all demands are met. However, rank-and-file workers continue to vote for new actions and show solidarity with other sectors. Wednesday’s “mega strike” was an expression of workers’ power, and shows the way forward to achieve their demands.

Originally published in Spanish on February 2 in La Izquierda Diario.

Translated and adapted by Otto Fors

The post British ‘Mega Strike’: Half a Million Workers Bring UK to a Halt and Protest Government appeared first on Left Voice.

Meeting the social needs of the world’s population through the production of goods and services depends on the amount of labour employed (in numbers and hours) and on the productivity of those of employed. Under capitalism, of course, what matters more is the profitability to the owners of the means of production from employing workers and in investing in productivity-enhancing technology. It is a fundamental contradiction of the capitalist mode of production that the required profitability of those owning the means of production becomes an obstacle to the required production to meet the social needs of the billions of humanity (and, for that matter, to sustain the health of the planet and other species).

About three years ago I posted some thoughts on the global decline in population growth and the future size of the global workforce available for capital to exploit. It’s worth updating the story. It took until the beginning of the industrial age for the global population to reach a billion and then another century to reach two. That was in 1927. By 1960 the next milestone of 3bn was reached – an interval of just 33 years. Since then, it’s taken only around a dozen years for each incremental billion expansion in world population. There are now 8 billion homo sapiens on the planet.

The main reason for the acceleration in population during the 20th century was the dramatic fall in mortality, the result of wider application of medical advances like better sewage, cleaner water, vaccinations against raging diseases and effective medicines etc. As a result, life expectancy at birth has increased by around ten years in rich countries. And despite the COVID disaster, which saw a general fall in life expectancy in many countries, the rate is still over 80 in the richer countries.

And even in low-income countries, it has risen to 63, an effective doubling since 1950. This was due principally to dramatic reductions in infant mortality in poorer countries. In 1972, around 14% of Indian and African newborns didn’t survive their first year. Those proportions have since declined to 2.6% and 4.4% respectively.

So life expectancy has risen sharply, driving up population. Capitalism however threatens further progress in life expectancy. It’s not just the impact of the COVID pandemic, particularly on life expectancy in the poorer countries. US life expectancy was falling even before the pandemic. According to US Center for Disease Control and Prevention data, more than 100,000 Americans died of overdose in 2021, representing a fivefold increase over the last 20 years. That figure is now on a par with diabetes-linked deaths, which are up “just” 43% over the same period.

The US has long suffered an opioid epidemic. This used to account for around half of all overdoses – mostly from prescribed painkillers and drugs like heroin and methadone. But since 2014 the death toll from synthetic opioids, mainly Fentanyl, has gone through the roof. In 2021, they played a role in two-thirds of all overdose fatalities. On current trends it won’t be long before Fentanyl alone claims more victims than diabetes. The difference for life expectancy being that whereas Covid and diabetes generally kill the old, Fentanyl disproportionately affects the young (around 60% of opioid deaths are in those under the age of 45).

Indeed, the 21st century marks the peak in the rate of population expansion. According to the UN’s latest projections, it will take 15 years to reach 9bn and then a further 21 years to reach 10bn, before the world population peaks at 10.4bn in 2085.

The driver of this deceleration is a steady reduction in the number of children each woman bears during her lifetime. Over the last half-century, the total fertility rate (TFR) has halved. Again, this is due to medical advances like contraception and urbanization where large families are not necessary to farm the land. Most human beings now live in cities and towns. Global fertility is now down to 2.3 live births per woman. More than half of all countries – including the two most populous nations, China and India – are actually below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per couple. Some territories in East Asia (e.g. Korea and Hong Kong) have a fertility rate below one.

That brings us to the crucial figure for capital – growth in the working age population. In the decade to 2022, the working age population expanded by around 1% p.a. globally. But that was less than half the rate prevailing in the second half of the 20th century. Many large countries will see their workforce decline from hereon. The demographic ‘crisis’ so often referred to for China applies to many other major economies.

The available global workforce for capital is set to decline if current trends continue. Can this be compensated for by faster growth in the productivity of the existing labour force? Well, despite all the promise of the internet age, trend labour productivity growth, as measured by output per hour worked, has actually slowed markedly over the last couple of decades. It now averages just 0.6% p.a. across the bloc of G7 economies. That’s the slowest it’s been in the last half century.

I have explained the reasons for this general slowdown in the productivity growth of labour in previous posts. The long-term decline in the profitability of capital globally has lowered growth in productive investment and thus labour productivity growth. Capitalism is finding it ever more difficult to expand the ‘productive forces’.

The US economy is the best performer of the major advanced capitalist economies at only 1.4% annual labour productivity growth over the last five years. All others are at a sub-1% annual pace. If we now combine these trend productivity growth numbers with likely working age population growth, we glean an insight into future GDP growth prospects.

The Anglo-Saxon economies, boosted by net immigration, may be able to sustain positive real GDP growth – but at a pathetic trend rate of 1.0-1.5% (at best), well below 20th century trend. Japan and the Eurozone economies, are heading for a post-growth existence, with trend real GDP contraction of as much as 0.5-1.0% p.a. So if you support the idea of ‘de-growth’, then you will get your wish in those regions over the next decade. And remember, these long-term projections ignore the probability of sharp slumps in production and investment in every decade ahead.

All this suggests that the capitalist mode of production is in a terminal phase. However, there are still areas of exploitation of labour that have yet to be fully tapped by capital. Half the projected next billion increase in global population in the 15 years to 2037 will be in Africa. Indeed, thereafter, the entirety of net world population growth will be African!

Capital can expand if it can increase value from the exploitation of more labour or increase the rate of exploitation of the existing workforce. The latter is increasingly difficult and growth in the former is decelerating – except in Africa. This continent has suffered centuries of slave exports to the advanced world and the break-up through colonial occupation of its native lands. Now it must face the prospect of increased exploitation of its burgeoning workforce as capital seeks new sources of labour to boost profitability.

January 20, 2023 Length:4560 words

In December 2019, the police in Wuhan, China, issued a news release about “medical staff fabricating rumors about the discovery of SARS.” Within the following month, the world was shocked by the outbreak of New Crown Pneumonia in Wuhan. The paralysis and incompetence of the Chinese government in responding to public health and safety incidents was exposed. With the principle of “everything for stability,” the Chinese government immediately closed the entire city of Wuhan and gradually extended the epidemic containment policy to the whole country.

Although the policy differed from province to province, almost everyone was subjected to it: confinement to their homes, strict community rules on the number of times they could go out each week; increasingly high prices for consumer goods, and even a lack of food in areas where the epidemic was severe; if an infected person was found in a community, the patient would be isolated (later on, the conditions of isolation became worse and worse, even without medication and beds for the patient). The community as well as the patient would be isolated, safe distances were guaranteed, and the community, as well as the county in which it was located, would be completely closed off. The government made it compulsory for everyone to have regular nucleic acid tests, which had to be done almost daily for a long period of time. School children were unable to return home after the holidays; workers and some petty bourgeoisie who were out of work at home had no source of income; small business owners went out of business or even went bankrupt as they have fewer and fewer customers; even a section of capitalists with fewer assets were threatened with bankruptcy.

The policies pursued by the Chinese government in 2020-2021 were a short-lived victory, relying on the continuation of campaign-based governance (large-scale closures even became the norm). During this period, the authorities promoted “dynamic zeroing,” the failure of Western bourgeois democracy, and China’s “institutional self-confidence” and “great spirit of resistance to the epidemic.” But the seeds of the 2022 crisis are buried in this success. Because of the sluggish economy, the government had to sacrifice the living conditions of the masses in order to maintain the containment policy, which was the source of public discontent; because of the greater financial and administrative power of local governments (and the influence of moderate factions within the Communist Party), some local governments (especially those that were economically backward) relaxed their epidemic prevention policies to a limited extent from 2022 onwards, but this led to the even-faster spread of the mutated virus. To counter it, the central government again continued to give instructions to the localities, which had to continue to sacrifice the living conditions of the masses to keep their finances in balance.

It was the Chinese bourgeoisie itself that caused the mass movement at the end of 2022.

The Struggles in Foxconn and Zhengzhou

Zhengzhou is the capital of Henan Province (China’s most populous province), a city that is both a hub for rail transport in China and a leader in manufacturing. Since 2010, Foxconn has signed a cooperation agreement with the Henan provincial government to build a vast system of factories in Zhengzhou. According to the most important official mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, the Zhengzhou Foxconn factory had at its best produced more than half of the world’s Apple phones, driving more than one million local jobs and training a cumulative total of more than three million skilled workers. In addition, the industrial transformation undertaken by Zhengzhou, the provincial capital, has made Foxconn the sole industrial pillar of the entire city.

In October, there were numerous claims that the epidemic had also reached the Foxconn factory campus, and there were reports that workers had to work with illnesses and were often not allowed to go out for leisure. Eventually the Foxconn factory, which was already accused of practicing a sweatshop system, was met with a revolt from workers—many fled the factory and began walking home on foot from the motorway. The factory was forced to send workers back to their hometowns due to pressure. As a result, in November 2022, Foxconn announced an urgent need to recruit 100,000 workers due to “employee resignations.” This was partly because many people had given up their jobs and the factory had to recruit in large numbers to meet the demand for the new Apple phones, and partly because the three-year epidemic closure policy had led to the closure of many small industries in Zhengzhou (and indeed the whole country)—in some places less than half of the shops in the whole shopping street were still open! The government had to opt for a massive restart of industrial production. In order to support the industrial backbone of Zhengzhou as a whole, Foxconn factories claim to be offering their workers “the best deal in a decade”: an hourly wage of 30 RMB (until 15 February 2023); extra bonuses for perfect attendance; and improved living conditions for workers. Not only are Foxconn factories recruiting nationwide, but the Henan provincial government has also mobilized a pool of strong rural labor, unemployed youth, grassroots Communist Party cadres and even ex-soldiers. Some local governments have even set clear targets for recruitment. Attracted by the vigorous operation of the state machinery and the generous remuneration, the Foxconn factory achieved its target of recruiting 100,000 workers in five days.

However, after the workers arrived at the factory, the capitalists quickly changed their attitude and broke the original high-tech contract, trying to “put the labor issue on hold” in order to start work as soon as possible. What is even more frightening is that a crack has finally emerged in the official, so-called dynamic zero-zero defense [against Covid]. As a result of the rush to gather labor from all over the country to resume work and production as soon as possible, a large number of workers were infected with the new coronavirus, which began to spread on a large scale on November 20. The bourgeoisie, however, did not show any mercy to the sick “workforce” and on November 21, when work resumed at Foxconn’s Zhengzhou plant, a large number of workers who tested positive refused to go to work because of their illness, while workers who tested negative demanded to “return to work after the plant has been cleared” because of their fear of their disease. The workers also demanded that the factory be cleared before they could return to work because of their fear of illness, and produced labor contracts stating that if the zero-Covid policy could not be implemented, the employer would have to pay the relevant amount as stated in the contract.

Invalid contracts, heavy labor; an out-of-control epidemic, a false zeroing out; an angry working class and a bourgeoisie bent on preserving its own interests and in collusion with the bureaucratic clique. These finally led to the intensification of the conflict and the beginning of the struggle. On the night of November 22, the workers, whose negotiations with the capitalists had broken down, directly launched a violent struggle, gathering inside the factory and launching a storming of the management area inside the factory. From November 22 to 23, the Henan government mobilized a large police force in the vicinity of the factory. There were violent clashes between the workers and the police: both sides attacked each other with sticks. Some video footage shows how the wall of police was beaten back by the agitated workers. On the morning of the 24th, the Foxconn factory finally gave in to the workers and gave each of them 10,000 RMB before sending them home. There have been some scattered struggles around the Foxconn factory since then, but the overall situation has calmed down.

Three things are noteworthy in this struggle: 1) apart from the ordinary civilian police, the armed police, who are part of the national defense force, have also been deployed in a massive crackdown, which means that this movement, although still pursuing economic interests, has gone beyond those legitimate struggles of the past in the eyes of the authorities; 2) instead of wearing their own uniforms, the police are all wearing the protective clothing of medical personnel. Symbolically, the government itself unveiled the class nature of the anti-epidemic policy: the defense of the state apparatus in the interests of the bureaucratic-capitalist alliance (or more precisely, the fusion of Chinese bureaucrats and capitalists as a whole into one class, not just an alliance), rather than the communist propaganda of “serving the people”; 3) The workers have not set up their own organizations (which is also unrealistic, as most of them only work short hours), nor have they created or used traditional media (newspapers, leaflets, etc.), but have used short videos or live broadcasts through software platforms like Tik-Tok to carry out spontaneous propaganda activities. This shows both the creativity and the immaturity of the workers: the software used by the workers has always been considered by the intellectuals a “hedonistic tool to corrupt the minds of the people,” but their use has forced the intellectuals to reflect on their superior attitude; but while the workers broadcast their violent struggle against the capitalists and government policies, they thank those who rewarded the viewers of the broadcast. The consciousness of the masses remains mixed. More importantly, no Marxist ideological group has intervened in this workers’ movement—in fact, there is no strictly Marxist organization in China at present.

Another issue of concern is the relationship between the Foxconn workers’ movement and the subsequent protests. As will be discussed below, there is a certain disconnect between the heroic actions of the workers and the protests of the university students and citizens. Indeed, most people are only aware of the Urumqi fires and not the Foxconn workers’ movement, and the workers’ actions had only a small impact on the student movement in a limited journalistic sense.

Fire in Urumqi

After the end of the Foxconn workers’ movement, a fire suddenly broke out in Urumqi, the provincial capital of Xinjiang, on the evening of the 24th. Officials claim that only 10 people died, but the citizens of Urumqi (through their WeChat App, rather than underground newspapers) generally question this result. The masses believe that the death toll is far greater than the official figure and that officials must be held responsible for the deaths; some claim that the authorities were unable to get the fire brigade close to the building, in line with the anti-epidemic policy, and that people were burned alive because the access doors to the residential building were blocked. When the official press release said that the matter was not serious, there were many skeptical voices on the internet.

Urumqi citizens spontaneously mourned the dead, which later turned into a protest that took to the streets. At one point the protesting citizens stormed the front of the city government building, which prevented the leaders of the Urumqi government from engaging in dialogue with the crowd, a first for China in the 21st century. On the following day, the 26th, the Urumqi municipal government declared the epidemic “zeroed,” ending the closure of the city that had begun on August 10th, and the whole of Xinjiang was gradually allowed to enter and exit freely.

Many Chinese analysts—largely Liberals, but also some Marxists—claim that this signifies an awakening in this minority Uyghur province and a direct revolt against Chinese Communist rule, but the true reaction of the masses is far from being summed up in this way. In fact, under decades of rule, an increasing number of Han Chinese—the main ethnic group in China—have been pouring into northern Xinjiang, outnumbering even the native minorities. It is true that the ethnic minorities are subject to more government control—for example, their passports have to be stored in police stations and cannot be used at will—but in this instance it cannot be said that ethnic sentiment among the minorities was mobilized, let alone that the citizens of Urumqi saw themselves in rebellion against the Chinese Communist Party. Even when the marching crowd broke through the police and rushed to the city hall building, they still sang the Chinese national anthem. In one iconic photograph, citizens representing the resistance still held up the Chinese flag.

In fact, discontent with the “zero-covid” policy—and furthermore, disquiet over the economic crisis, as the lower-class masses were denied access to the workplace and lost their work income—was the main cause of the events in Urumqi and the series that followed.

Protests in Schools

The events in Urumqi set off a wave of protests across the country, and on November 26, students at Nanjing Media College spontaneously mourned the victims of the Urumqi fire and held up [pieces of] white paper in protest. In the days that followed, 207 schools across the country saw posters of protest or gatherings of protest.

The consciousness of the students was more complex, but remained primarily opposed to the “zeroing” policy—students entering university from 2019 onwards have had little freedom to go out throughout their university life. On the basis of this common consciousness, a number of universities have seen the emergence of the liberal slogan that appeared in Beijing’s Sithongqiao on the eve of the 20th Communist Party Congress: “No to Cultural Revolution but Reform.” These liberals believe that the Chinese authorities are following the old path of the Maoist era. But there was also the singing of the International and chanting of “Long Live the People” (a famous phrase used by Mao himself)” in the universities. Surprisingly, seven of China’s “Eight Great Academies” took part in the event; the only one that did not was the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts, which was put under martial law around November 21 after someone wrote the slogan “Down with Xi Jinping” on the walls of the school. An impressive poster at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, based on a poster from Mao’s time, read, “If art does not interfere with politics, it will die because of political interference.” In some universities, statues of Chen Duxiu, ([the co-founder of the Chinese Communist Party, purged by Mao in 1927] who was suddenly brought back from the margins of history thanks to a TV series in 2021), Lu Xun (considered the greatest Chinese leftist writer and the “National Spirit” of China) and Nie Er (one of the authors of the Chinese national anthem) were also used by students to create political-artistic works.

Some Chinese Marxists did intervene in personally in the university protests, but on the whole those who sang the International and commemorated Mao were not all Marxist in orientation; this group of students was just as likely to be extremely opposed to the ethnic migration of Blacks into in Guangzhou as favoring the overthrow of the government. The International and Mao can be symbols of both revolutionary Marxists in China and of the “old Maoist left” who want the government to reform itself and move back to the path of “real socialism.”

Of those schools that had protests, media and art schools, which are considered to lack a tradition of humanistic criticism, tended to have larger protests, while those universities that are considered to be better (the so-called 211 and 985 universities) rarely protested. Peking University and Tsinghua University are considered to be China’s top institutions, but student protests there are far from comparable to those at Nanjing Media College; meanwhile the university acts in the first instance to continually pacify students and prevent anything from escalating into protests. The only exception may be Renmin University of China: students at this school, once considered to be in the conservative camp, staged a massive protest that directly secured the partial unsealing of the school.

Eventually, to prevent students from further inflaming the situation, the university decided to let students go home for an early holiday.

The Motivated Cities, the Quiet Villages

The students’ protests took place at a time when there were massive citizen protests in all of China’s major cities: Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Lanzhou and Chengdu. The most famous incident took place in Shanghai. The city has a road called “Urumqi Middle Road,” where citizens gathered spontaneously to mourn and protest. Here, for the first time, the crowd chanted “Down with Xi Jinping, down with the Communist Party,” followed by Chengdu, a large city in western China. The mass protests in Beijing were equally loud. In addition to the usual protests, the traditional Stalinist-Maoists in China were boosted by an anarchist sympathizer with Mao who urged the masses, “Down with revisionism, we want a democratic Communist Party.” The protests in the cities also affected Chinese students abroad, who launched protests all over the world. Like the citizens of Urumqi, the mass movement remained vague about its aims, even though the citizens of Shanghai and Chengdu raised the slogans “Down with the Communist Party” and “Down with the dictatorship.” The Chinese people, who have been ruled by political indifference for more than 30 years (since 1989), are still naive enough to fiercely raise one slogan when a movement breaks out, only to move on to something much more moderate, or perhaps even to the exact opposite. Just think about shouting down the Communists while holding up a portrait of Mao Zedong.

While the citizens of these major cities acted and set off a groundswell of discussion on the internet (and for Chinese people, mainly on Twitter, which is officially banned), the impact of the events on the whole country should not be overestimated. With a land area of 9.6 million square kilometers and a population of 1.4 billion, the population and area occupied by these major cities is not that large. More importantly, because the events depended on local sentiment towards local prevention and control policies, the vast rural areas and other large cities where the epidemic was not serious (such as Chongqing, a city of at least 10 million people) did not feel the strong political shock. This is not only because mass discontent was greatly influenced by the intensity and contingency of the prevention and control policy, but because people in the rural areas had no idea what was happening in the cities: the Chinese government’s control of speech led to a blockage of information, and those young people and intellectuals with access to information and political enthusiasm, even if it is vague, tend to congregate in the big cities. In this sense, China’s vast frontier is fragmented: the noisy big cities dominate the political movements and are visible to outsiders, while the silent vast countryside is often overlooked. On the other hand, the spatial separation of the masses from each other prevents the lower classes from forming a common anti-capitalist front, and even workers find it difficult to form some kind of network of contacts across regions (let alone nationwide).

Chaos After “Living Together”

On December, 7 the Chinese government issued a new “Ten Articles of Prevention” which removed all mandatory nucleic acid requirements and mandatory quarantine restrictions. Naturally, this meant “Living Together” with COVID-19 in China.

The Chinese Ministry of Health claimed on December 24 that there were 4,103 new cases in the country on a single day, compared to 31 in Shandong province, but according to an official in Qingdao (a city in Shandong), there were some 500,000 new cases in Qingdao on a single day! The policy and ideological reversal have provoked violent reactions in all sectors of society: there is anger at the manipulation of medicine by capitalists, doubts about the policy shift, fear of the virus, etc.

The “Living Together” policy shift has made Chinese society a more fractured one and is substantial evidence of the fusion of bureaucratic decision-making groups with the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois character of its political decision-making. Here, scientific standards of prevention and control and a rational understanding of the virus can only serve the needs of bourgeois profit production and capital appreciation—that is, the reproduction of capitalist relations of production. The official media have invented a term: pyrotechnics. It symbolizes the “full recovery” of the tertiary sector, especially the catering and entertainment industry, after “Living Together.” At the same time, capitalists from the coastal provinces were the first to fly abroad in search of manufacturing orders.

But when the economy recovered in full, who bore the cost? Naturally, it was the Chinese proletariat. Employees and manufacturing workers and millions of healthcare workers were told to work with maximum efficiency in the production [for the sake of the bourgeoisie. Many have paid with their lives, for example, the sudden death of Chen Moumou, a 23-year-old clinical postgraduate student at West China Hospital, who was positive with a disease on December 14.

This is the blood debt of the Chinese bourgeoisie.

On January 7, more than a thousand workers in Chongqing were laid off from their jobs at a factory producing antigen testing kits. The angry workers smashed machinery, burned the goods they produced, mobbed the factory’s senior management and its agents (the absolute majority of the workers had been recruited by labor companies, which were also responsible for their wages) and clashed violently with the police who came to maintain order.

Less than an hour before these lines were written, the capitalists had compromised with the Chongqing workers and the police had largely withdrawn from the factory.

Until 2022, economic struggles waged by the Chinese proletariat usually ended in government mediation, but from the Foxconn factory movement until the Chongqing workers’ riots today (January 7), the proletariat’s economic struggle has increasingly taken the form of large-scale violent clashes, a new form that indicates a new phase in the workers’ struggle and poses a serious task for Chinese Marxists.

The Conditions of the Chinese Left

The Chinese leftists we are talking about here are not the university professors (some of whom are called “New Leftists”), nor are they reformists who want the government to return automatically to the path of “real socialism.” For half of the world that enjoys bourgeois democracy, the form of existence of the Chinese left is necessarily very strange.

In 2017-2018, two more serious Marxist groups formed in China, both followers of Stalin and Mao, hoping to bring down the current capitalist China through a new revolution. But since the defeat of the Shenzhen Jias workers’ movement in 2018, both of these Marxist groups have been wiped out by the government. In subsequent years, Marxists have existed only in the form of circles of friends (and often online friends). In other words, there are no real Marxist organizations in China at present, not even local groups. As a result, the Left in the recent movement has been unable to act as a political collective and at best has been able to guide the surrounding masses as individuals.

Ideologically, it is possible to divide Chinese Marxists into three basic categories. The [first is the] Stalinist-Maoists, who occupy the absolute majority as a historical legacy, who do not have a worldview beyond that of the Soviet Marxists of the Stalinist era and believe that capitalism can be defeated simply by copying the theories of Stalin and Mao. [Second], as a result of the downturn in the workers’ movement and leftwing organizations, some Marxists in 2020 proposed a rethinking of the entire theoretical tradition, introducing Western Marxism and postmodernist philosophy (especially the latter). By denying Lenin and the revolutionary significance of the Russian revolution, these “original Marxists” turned Marxism into a product of research in the academy and opposed the creation of any political organization. What is interesting is that this tendency tends to be particularly keen on studying Zizek as well as cultural criticism. [A third group with a] historical legacy is Trotskyism. The theoretical struggle between Trotskyists and Stalinist-Maoists made may people realize the problems with the latter; but in the last few years, Trotskyist theories have no longer been able to satisfy Chinese Marxists because many of them have read the works of Western Marxists that question Trotskyism. So, while there are still many Trotskyists, they have fulfilled their historical task, which was to confront Stalinism-Maoism when Chinese Marxists were theoretically deficient.

These three groups of Marxists corresponded broadly to the three views on the November mass movement. Most Stalinist-Maoists saw the White Paper movement as an outright “bourgeois color revolution” caused by forces outside the country and that only Marxists should lead the workers’ movement. The academics refused to comment publicly on the situation and had no wish to get involved. Trotskyists and a small group of Stalinist-Maoists (and indeed some marginal Marxists, but they were often very individualistic) wanted to lead the movement themselves, but did not have a clear mandate or sense of organization.

Being entangled in history and the philosophy of the academy, it was practically impossible for the Chinese Left to fulfill the tasks posed by the mass movement. But this does not mean that Chinese Marxism has everywhere fallen into despair: some Marxists on the fringes of leftist circles have put forward their own views. One person who considers himself a Leninist wrote the following.

What is our task? Aspiring academic theorists and impatient practitioners disdain to answer this basic question. The former wrap themselves in revolutionary jargon, the latter self-righteousness blindly launch so-called propaganda and coalition campaigns. The theoreticians despise the practitioners who do not know the fashionable terminology, and the practitioners laugh at the rotten theoreticians. The former set up academic salons for their own amusement, reproducing pathetic academic rubbish (although they often look askance at academia since few are integrated into it), the latter do not understand the meaning of any Marxist organization and stuff all sorts of people in big tents for no good reason, or are stuck in long-dead Stalinist sects, which are nothing more than a repetition of a revolutionary comic fantasy. The two sides that despise each other are merely an endless reproduction of existing structures within the revolutionary movement, unwilling and unable to create a real revolutionary organization (or even its embryonic form).

We must think carefully about this quotidian question. Should we not accept without reservation an unreflected premise? Should we not first ask, who are we? In speaking about the necessity of a vanguard party, Trotsk, criticized those who used the experience of the Social Democratic Party to argue for the building a party of revolutionaries; he asked what is the resemblance between revolutionaries of the 20th century and Social Democratic Party bureaucrats. How can contemporary Marxists ignore the distinctions between themselves and conflate themselves with pseudo-revolutionaries? The question is first and foremost who “we” are.

We are revolutionary Marxists—at this stage—i.e., adhering to party-community relations in the sense of Lenin-Gramsci’s [concept of] leadership (not accepting narrow views of [party] indoctrination or proletarian spontaneity), revolutionary in general (not just transforming ownership of property, but creating new forms of human interaction), the dictatorship of the proletariat as created by the proletariat (whose form is unpredictable but always is based on the principle of self-management).

Determining whether this conclusion is correct still needs to be put to the test of historical practice, and the formation of a new generation of Chinese Marxist organizations is still on the horizon. But in any case, the presence of such voices does not entirely make Chinese Marxism the historical laughing stock that Marx spoke of in Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte; instead, it kindles as a kind of spark.

U.S. Labor Strikes Went Up Almost 50% Between 2021 and 2022

Greg

Tue, 01/17/2023 – 21:29

There is an international political economy of knowledge production, as ideas and theoretical debates are in many ways determined by material reality. Why is it that some concepts circulate so widely while others are a priori dismissed? Why is it that some seemingly radical frameworks find so much support in U.S. universities, while others are More

The post Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism: A Reactionary Work for a Counterrevolutionary Project appeared first on CounterPunch.org.