Archive for category: #Sensuousness #Feeling #Suffering #Emotion

Scientists used a quantum computer to explore the ultimate escape route from a black hole.

A mouse is running on a treadmill embedded in a virtual reality corridor. In its mind’s eye, it sees itself scurrying down a tunnel with a distinctive pattern of lights ahead. Through training, the mouse has learned that if it stops at the lights and holds that position for 1.5 seconds, it will receive a reward — a small drink of water. Then it can rush to another set of lights to receive another…

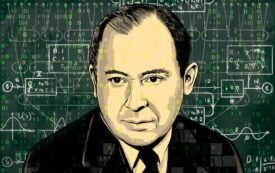

David Nirenberg

The post The World John von Neumann Built appeared first on The Nation.

In the Vietnam War era, radical psychiatrists and antiwar veterans developed a concept of trauma stemming from perpetrating acts of violence. Over the next decade, the idea of soldier trauma was depoliticized and put at odds with antiwar critique.

Vietnam veterans with PTSD march in the annual Veterans Day Parade on November 11, 2021 in New York City. (Andrew Lichtenstein / Corbis via Getty Images)

Nadia Abu El-Haj’s new book, Combat Trauma, explores shifting clinical and public understandings of soldier trauma from the Vietnam War era to the post-9/11 present. The book examines how the figure of the traumatized soldier frames an ethical commonsense about what American civilians owe those who fought in the military and how that consensus ultimately forecloses on the possibility of antiwar critique.

Abu El-Haj is a professor of anthropology at Barnard College and codirector of the Center of Palestine Studies at Columbia University. She sat down with American psychotherapist and Jacobin contributor Chandler Dandridge to discuss the radical origins of the concept of soldier trauma and its subsequent absorption into the pro-war status quo.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

After devoting your first two books to Israel and Palestine, Combat Trauma appears to chart new territory for you. What made you want to write about American militarism in the post-9/11 era?

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

My two previous books are interested in colonial and imperial formations on the one hand and disciplinary forms of knowledge that give you a heuristic into those formations on the other. Whether it was archeology or genetics or now psychiatry, I explore disciplines as a way of thinking about broader political and ethical questions of power, colonialism, and imperialism. So there is an intellectual and methodological thread here.

But it was also very personal. I lived in war zones as a child and teenager. I lived in Beirut. I spent a lot of time in the West Bank. And then I spent some time in Baghdad in the ’80s. I had an experience of war and occupation as a civilian in the war zone.

So when the post-9/11 wars started, it was unbearable to watch it unfold from here. It was so striking to see what it means for a country to have the power and privilege to go to war thousands of miles away in a way in which the costs are just not borne by the American public.

Within a year or two, I started encountering articles on soldiers who were traumatized, and the accounts were all of being traumatized by seeing their buddies blown up or something like that. Having done a post-doc in the history of science, I knew the literature on the history of trauma. And in particular, I knew the writings on the Vietnam War that had a very different understanding of soldier trauma. And then as the years went on, the figure of the traumatized soldier became so prominent in the press and popular culture that it became a way for me to think about how these wars appear on the American front.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

The book outlines the transition from what was once called “post-Vietnam syndrome” into what we now know ubiquitously as PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. How has the professional formulation of PTSD changed the trajectory of the traumatized soldier?

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

It’s changed profoundly. I start with the Vietnam period for a particular reason, which is partly in response to a scholarly literature on the origins of PTSD. The war in Vietnam and then the incorporation of the category of PTSD into the DSM-III marks a turning point when trauma becomes both acceptable and a condition of victims. But scholarly literature misses something really important about that earlier formulation. Today, a lot of work around trauma and war dismisses the possibility of trauma as a language through which one can capture the political stakes of these wars. Trauma is purely clinical and it detaches itself from any broader conversations about collective responsibility or collective experiences.

The concept of ‘post-Vietnam syndrome’ was developed by a group of radical psychiatrists and Vietnam veterans who were part of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

That wasn’t always the case. Within the movement against the Vietnam War, the concept of “post-Vietnam syndrome” emerged. It was developed by a group of radical psychiatrists and Vietnam veterans who were part of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). And the syndrome was simultaneously a psychiatric and political conception. The veterans understood themselves to have been traumatized by what they did; not by having been victimized, but by having committed atrocities on a regular basis. In other words, trauma was born in transgression. And understanding and healing trauma was inseparable from articulating a political critique of the war.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

We then enter the [Ronald] Reagan Revolution where it seems the administration was especially interested in restoring the image of the American soldier and the military. How did this contribute to the further depoliticization of combat trauma?

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

Various things converge in the 1980s to shift the understanding of trauma and to depoliticize it. As part of the rise of the conservative movement, Reagan sought to rewrite the war in Vietnam. One crucial piece to rewrite was that the US did not lose the war on the battlefields. It lost on the home front. The antiwar movement deprived the fighting force of their ability to do the job. Part of that reconstruction is a reconstruction of the treatment of Vietnam veterans upon their return. So, it’s not just that the war was lost on the battlefield. It was that trauma was produced by a homecoming as well, because of the ways in which the Vietnam veteran was demonized. So you have a political shift that’s inseparable from the trauma conversation.

There are then other things going on at the same time. There’s obviously the feminist movement that really gains much more ground on questions of rape and incest in terms of both public recognition and juridical rights. They rely on the work of the antiwar psychiatrists to formulate their understanding of PTSD. They needed the victim not just for political but also for forensic reasons, because the argument was always, “Are women really innocent of rape?”

And then there was also this conservative movement called the “Victims of Crime Movement” that the Reagan administration championed. And their argument becomes that the streets are dangerous; normal (white) Americans can’t walk the streets without being at risk of murder and rape. That movement also picked up the language of trauma, the trauma of the innocent, victimized citizen who was preyed upon by the (black) criminal in the public domain.

So you have all these different political projects that converge around the notion of trauma, and gradually the concept moves farther and farther away from its original understanding, not just as a political critique, but as the possibility of being traumatized by having been a perpetrator of violence rather than a victim.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

The post-9/11 wars have given us an entirely new category of soldier: the drone operator. I am wondering if you could talk a bit about the concept of combat trauma when it comes to the drone operator.

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

The traumatization of the drone operator is really interesting, because it does not use the language of perpetration and transgression. But there’s no way you can frame it other than that the issue is the drone operator is perpetrating violence. The drone operator is killing. So they talk about killing at a distance and what that means. (Although the relation is very intimate and the question of distance is complicated here because, on the one hand, you’re geographically distant, but visually you see the person you kill in the community they live in as you are tracking them in a way that a soldier on the ground may not.) Clearly, the drone operator’s trauma cannot be about fear of death, exposure to bodily harm. About being victimized. But discussions of drone operator trauma do not enter explicitly into the language of perpetration.

There’s been a shift away from psychodynamic therapy, which has reduced the amount of care that is available to veterans in ways that I think could never possibly capture the actual depth of the problem.

You’ve often been watching this person for a long time. It’s theorized as the tension between, I’m clocking in a 9 to 5 job doing war and then I go home and pick up my kids from soccer. And the disjunction is just kind of an impossible thing to live. And there is talk about killing. But again, in a kind of neutered language. Because the question is never whether the killing is legitimate.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

Since Vietnam there has been a robust care system set up around veterans. I am wondering if you could talk about how this so-called “care industry” functions and how it “conscripts citizens,” to steal a heading from one of the book’s sections.

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

It is important to separate the federal government’s response from the private sector’s. The care industry is part of a whole transformation from Reagan to [Bill] Clinton to George W. Bush where cuts were made to federal welfare. It’s the neoliberal turn. You shrink the size of the welfare state and outsource a lot of the work that would have been done by the welfare state to nonprofits. It’s not the role of the state to care for its citizens in the same way. The retraction of the welfare state is when you see the expansion of this whole nonprofit world taking up a lot of the work of care.

When it comes to veterans and the VA [or the US Department of Veterans Affairs], there are problems that I think are both paradigm problems and fiscal problems. There’s been a shift away from psychodynamic therapy in which Vietnam veterans who still went to the VA were being treated therapeutically for years on end, toward the introduction of evidence-based medicine where it’s about supposedly measurable outcomes and short-term care, which is a lot cheaper. It has to show improvement. The paradigm shift has reduced the amount of care that is available to veterans in ways that I think could never possibly capture the actual depth of the problem here.

But the care industry, as I see it, is much more the nonfederal part. When you outsource the care, it’s not framed as an institutional federal responsibility. It’s framed as an obligation of citizens who didn’t go to war toward those that did. And it depends on this very stark dividing line between the civilian and the soldier. And here “the civilian” refers to the American citizen who apparently doesn’t know violence, which is an extraordinary statement given the society we live in. But there is a sense of being ignorant and an innocent of violence, of war. And that care industry is about healing. It’s about reintegration. But it’s done in a language that is stripped of any political critique.

As I write in the book, I’ve been to all these conferences where people are being trained in how to treat trauma and they tend to be liberals. They tend to be people who were definitely against the Iraq War, if not the war in Afghanistan. But there’s still a sense of that not being something we have the right to speak about. The treatment and reintegration of veterans has nothing to do with taking a political stance on the wars. More than that, taking a political stance on the wars can be seen as not supporting the troops. So, working with soldiers and veterans is framed as a profoundly moral obligation, stripped of any political entailments. And what that ends up doing is sidelining one’s position on the wars as somehow tangential to reintegrating and healing troops, or even, to conversations about the wars, because so much of the focus is on healing American troops. That’s what the war appears to be. In the American public arena, the war appears as the wounded or, I think even much more profoundly, the traumatized soldier.

Working with soldiers and veterans is framed as a profoundly moral obligation, stripped of any political entailments. And what that ends up doing is sidelining one’s position on the wars as somehow tangential.

There was one session in this conference where veterans got up to speak to the audience. And the chaplain, a former military chaplain who introduced the veterans, told us, “Put down your pens. You are here to listen. They have decided to grace us with sharing their experiences and our job is to listen.” Our only job is to listen because the whole question of reintegration and healing is framed as a project of listening without judgment. Now again, one understands that in the context of a psychiatrist’s office. But there’s a broader call here, that’s a political call as well, to “support the troops.” Two out of the four veterans themselves levied incredible critiques of the war, but in people’s responses nobody picked up on that. They wanted to talk about the suffering.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

The book touches upon figures like ex-Marine Tyler Boudreau who have become critical of US militarism in the Middle East. What do you think distinguishes the post-9/11 soldier who reckons with their trauma through political critique?

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

I think people like Tyler Boudreau came to their political critique through their experiences. They go off to war thinking they’re fighting the good fight. And then they encounter a war that makes no sense to them, how it’s being fought is unacceptable to them.

I know somebody who was involved in the first siege of Fallujah. He was a working-class kid and he went off to war and he really believed in it. And then they decimate Fallujah and he cannot reconcile what they did militarily with what he was led to believe the war was about. I think that happens to a lot of people. But I think there’s a difference between disappointment and politicization, and there’s a lot more disillusionment than politicization.

The turn to politicization? Why some individuals and not others? I don’t have an answer, but what’s interesting is that there is no question that someone like Boudreau and other veterans have the right to speak critically and politically about the war because they were there. But the rest of American citizens? Well, you didn’t go. You didn’t sacrifice. You can’t really critique.

I think in complex ways the liberal to left public has gotten on board with that call for silence, because so much of the conversation actually remains about American soldiers and their suffering. What do we owe the soldier? And in the scholarly world, so many books and ethnographies about the war are all about American soldiers or veterans. Part of that is access. But I don’t think that’s the only thing.

So that was part of my challenge. How can I write a book that stays in the US but doesn’t stay inside this American nationalist imaginary?

- Chandler Dandridge

-

I’m thinking of the post-9/11 soldier-turned-politician. It’s almost impossible to imagine a critical figure like even a John Kerry running for office today.

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

I think there are veterans who are critical of the war running for office. But not in the way the VVAW was. It is very different to say the war was badly run, or that the Iraq War was started on a lie and that we shouldn’t have been there, than it is to say this is an imperial war and we really have to reconsider the US’s role in the world. That was the VVAW’s politics, or at least many of its most vocal members’. Those are very different kinds of statements.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

Even on the Left, antiwar sentiment is so muted. Not that there was a large antiwar movement under [Barack] Obama, but there was still a sense of a conversation happening.

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

How can you claim to be in a progressive movement that is opposing the rise of the Right and not think it’s even worth talking about or demanding the end of American military intervention? What makes that possible? I think it’s this kind of hagiography around the American soldier and, in particular, around the figure of the traumatized soldier. I don’t think the wars have been absent in the public domain. As I argue, I think they’ve been incredibly ubiquitous. But the soldier stands in for the war. The traumatized soldier is the war.

The soldier stands in for the war. The traumatized soldier is the war.

- Chandler Dandridge

-

In the book’s epilogue you write about the US withdrawal from Afghanistan followed shortly by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. How do you see these two events contributing to a critique of US foreign policy?

- Nadia Abu El-Haj

-

There hasn’t been a sustained political critique of the “war on terror” and US empire. And for one thing, it’s not over. The spectacle with which Afghanistan fell to the Taliban was an incredible smack in the face to the US military. Again, it didn’t lead people to say, “Wow, maybe the war was illegitimate from the start, or at least not the smartest response or the most moral response to 9/11.” But it did lead to this sense of American failure. And there was certainly at that moment, and it was really only a moment, suddenly a conversation about, “Oh my God, all these people who worked with us and fought for us and we’re abandoning them.” There’s a moral failure built into that military failure.

Then the war in Ukraine begins. And let me be clear: it’s an illegitimate war. It’s a war crime. Russia can’t be invading Ukraine. But that’s not the question — as if the US has not invaded sovereign nations for no good reason. Ukraine: it’s like the good fight that the Americans ultimately didn’t find in Afghanistan and Iraq. You’re fighting on behalf of Ukrainians who are fighting for democracy and the liberal order. The US can now be the moral leader again. It can organize the arms shipments and get the Europeans on the same page. And, in fact, it can do it without putting any of its own soldiers at risk.

What really struck me from an American perspective was, briefly, there had been some critical kind of reckoning. I mean, whatever that means with the fall of Afghanistan, right? And then it just gets taken over by this war in Ukraine and the US comes out looking rosy again. Partly that’s because the Russian military fought the way it did in Syria. Nobody cared as much when it was in Syria, but the Russian military doesn’t even have a pretense to a liberal way of war. It flattens cities to get what it wants. The American military has a pretense to limiting civilian casualties unless absolutely necessary, so American generals can stand up and lecture Russians on war crimes.

After the fall of Saigon, there was a kind of forced reckoning with the war and its failures. That’s what Reagan responded to. He had to reconstitute a military that was deeply delegitimized. But the military was never delegitimized by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, because somehow the failures were not their responsibility. It was always only the politicians’ responsibility.

I feel like there’s never going to be any sort of reckoning. We’ve just kind of whitewashed over it all. I’m not sure there would have been, but there’s not even a possibility now. Because America’s virtue as a democratic leader of the world, fighting the good fight, has just been reconstituted kind of seamlessly.

Avery Wear: Could you talk a little bit about who you are? You founded the Indigenous Sovereign Nations (ISN) Employee Resource Group for San Diego County employees this year. What led you to start this?

Maria Whitehorse: I have been a San Diego County employee for 15 years. I’ve also been a union advocate for about 13 years and I’ve lived in San Diego all my life.

Having an Indigenous family and seeing the disconnection from the culture relit a fire that I’ve had for years on educating the community and bringing visibility to the culture.

I know there is an unfair history that is being taught about my ancestors that has no validity and must be corrected. By forming this group, I wanted to address this and have the community unlearn and relearn the culture the right way through the testimonies of my ancestors and just everybody who is tribal, connected tribally to a tribal affiliation, or who has Indigenous family and ancestry.

Brian Ward: The ISN joined the Orange Shirt Day, which commemorates the sufferings of Indigenous children in Indian Boarding Schools. You all asked the county to join the commemoration by lighting the downtown county building orange that night. At first they refused, but later they felt they had to do it. How did that come about?

MW: I’ll give a quick history about Orange Shirt Day, which was where the request came from. The Orange T-shirt is a memorial to the children who were stolen from their tribes and put into boarding schools to assimilate, which took away their tradition and their cultures.

They obviously endured trauma. Some of the children died of starvation and illnesses. I felt a need to give honor to these children. A lot of people think that this started in Canada (which it may have), but we also had boarding schools here in the United States, particularly here in California. The few boarding schools here in California that have been recognized led us to request a building to be lit in orange to honor these children on September 30.

We requested that the County of San Diego light the building. Unfortunately, there was a disconnect in communication regarding getting the building lit which prompted us to request a meeting with the Board of Supervisors [Chair] Nathan Fletcher. In that meeting, there was myself representing ISN and a few tribal members. We spoke about what transpired in terms of getting denied to light the building for the children.

He agreed that this needed to be honored and needed to be done. He agreed to go ahead and light the building on November 2 in honor of the children. However, we did mention that this was a little late. Had this been on September 30, it would have had more meaning.

This memorial was lit in memory of not only the children that were killed but also the survivors, because we have a lot of children that did survive these boarding schools and they’re very impacted by the trauma. Lighting the building in orange is in memory (and honor) of them because they did pay an ultimate sacrifice to their relations.

The San Diego County Administration Building lit orange on November 2, 2022 in honor of Orange Shirt Day. Photo by Maria Whitehorse.

The San Diego County Administration Building lit orange on November 2, 2022 in honor of Orange Shirt Day. Photo by Maria Whitehorse.

AW: San Diego County has the largest number of reservations of any county in the U.S. There’s a long history of Indigenous struggle in this part of the world. How do you see ISN as a new organization of county employees fitting in with this ongoing historical struggle?

MW: I believe that ISN is ready, equipped to educate, and able to give the space to do so. Visibility is important: putting on events and showing our culture. I know our culture has its struggles, but we are survivors. We were once marked for extinction. But we are still here.

It is also important to discuss how poverty and economic barriers lead some Indigenous people to leave their communities because they want a better life for their families. But leaving reservations makes them lose their culture and traditions.

The purpose of ISN was to give that safe space to reconnect those that chose to leave their culture in search of a better life. And we are not only one tribe; we are all-inclusive from the North to the South. We’re a safe space to learn from each other’s traditions and cultures. It’s just an open space to reconnect.

BW: Regarding Indigenous peoples leaving reservations and going into cities looking for different opportunities, an overwhelming majority (about 72 percent of Indigenous people) live in urban environments. Were there any organizations, or things that you saw, that inspired you to create ISN and connect to issues specifically for urban Native folks?

MW: We live in the county of San Diego, which is Kumeyaay Nation.

We also have an array of other tribal people that come from around South America. From what I’ve seen, the people from Oaxaca suffer tremendously, as well. First, because the government says they are illegal when this is their land. There’s a saying: “we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.” They don’t live on a reservation. They’re urban Indigenous people. They live in town with us. And not only Oaxacans. There are other people who I have met who belong to tribes that have been detribalized. They’re not recognized because the government has unrecognized their tribes going back to the sixties and fifties. So they have no reservation or recognition, but they live in urban areas. The goal is to reconnect them and help them come back to their roots.

“There are many that come as a savior, but the people don’t want that.” They don’t want that savior. It’s gotta come from within them, inside the reservation.

It’s much too easy to say, “I’m going to leave my reservation because I want a better life.” But they have sacrificed their traditions and culture to do that; to live here in an urban area as a Native. I want to bring out that Native in them because there are many who don’t recognize that they’re Native because they weren’t raised like that, because their parents were ashamed or because of the stigma that comes with it.

I want to take ISN to help urban Natives, too. I know we have lots of them in San Diego and I’m hoping that they will reach out so that we can come together in our relations and help others.

I met a woman who was from the Pine Ridge Reservation. If I’m not mistaken, they’re one of the poorest reservations out there. They’re the ones that I believe are being punished for the killings and the history done to them. When we discussed Pine Ridge, she said, “There are many that come as a savior, but the people don’t want that.” They don’t want that savior. It’s gotta come from within them, inside the reservation. But maybe I can extend the education here on what that reservation is going through; maybe send some kind of message or some kind of help. Not being a savior but allowing them to be self-sufficient, because it’s got to come from within. And unfortunately, they’re very oppressed because of everything that’s gone on with them and the way the government has Pine Ridge situated.

This discussion with that young lady that was from Pine Ridge was one of the sparks that lit a fire in me. She lives here in Oceanside. She is an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota Tribe as well. However, she also sought a better life and is living over here in California.

To hear her experience and perspective as someone who was born there, you see things in a different light. That’s what I mean when I say, “unlearn to relearn.” I want people to “unlearn” in order to “relearn” the right way.

BW: You and several other ISN members are also union activists. How has your union background shaped your approach to ISN’s work?

MW: I think being an advocate is in my DNA: to be able to organize and create those groups that are safe spaces to discuss, share and make sure everybody has a voice in this march and in this struggle together.

Union ideas align with what I envision for Indigenous Sovereign Nations and what our group can do for our Indigenous community. For me, advocacy comes naturally. And most of my members or board members are all advocates themselves and I think it runs in their DNA, as well. So, I think our group is composed of phenomenal people that will help to bring this group to light in order to help the Indigenous community.

AW: How do you see ISN fitting in with other fights for social justice, including the workers movement?

MW: The ISN aligns with other fights because what I envision for Indigenous people is that everyone deserves economic equality, political and social rights, and opportunities. Indigenous people and their communities have suffered from being left behind.

I believe that ISN can be that safe space where we can give that visibility to the community, Indigenous communities and peoples, so that they can be put in the front.

Maria Whitehorse (right) stands next to members of the Indigenous Sovereign Nations (ISN) Employee Resource Group outside the San Diego County Administration Building. Photo by Maria Whitehorse.

Maria Whitehorse (right) stands next to members of the Indigenous Sovereign Nations (ISN) Employee Resource Group outside the San Diego County Administration Building. Photo by Maria Whitehorse.

BW: What are your visions for society in the long run? Do you see a connection or relationship between ideas of Indigenous liberation and socialism?

MW: Mine is to change the mindset of colonialism. That is my main target.

The Indigenous people were marked for extinction, but we are still here. So our aim is to make our ancestors proud. Some of them paid the ultimate sacrifice (if not all) from the colonizations of the Americas to today. Indigenous people faced and continue to experience oppression, disenfranchisement, discrimination, and some of them even violence at the hands governments, institutions, racism, and colonialism.

Indigenous people have been silenced and have encountered institutional barriers with far-reaching impacts on education, economy, justice, and the environment. What I want this group to do is the work of addressing historical, generational trauma. It can only begin to heal if the harm and the abuses are understood.

If we unlearn what’s been taught and reteach it the way our ancestors survived it, through their eyes, we can address and dispel all of it.

The hope is to bring honor to our ancestors through hard work, dedication, keeping sovereignty, culture, health, and wellbeing for our future generations.

Featured Image credit: Photo from The Province of British Columbia via Flikr; modified by Tempest.

REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein

- For many Americans, Thanksgiving is about food, family, and saying what you’re grateful for.

- However, for Indigenous Peoples, it’s a day to gather to reflect on their heritage and past treatment of ancestors.

- Recognized as The National Day of Mourning, the event has been held every November since 1970.

Right now, as families across the country have gathered to cook, catch up, and remember what they’re thankful for, members from the Indigenous community have gathered by the statue of Wampanoag chief Massasoit Ousamequin, across the street from Plymouth Rock in Plymouth, Massachusetts ,to commemorate the 53rd National Day of Mourning.

Observed on the fourth Thursday of November each year, the National Day of Mourning is held by the United Americans Indians of New England (UAINE) so that members of the Indigenous community can reflect on their heritage and educate the masses about how their ancestors were slaughtered by foreigners who first arrived in the United States in the 1600s. The murders they speak about took place at the Pequot Indigenous Nation’s annual Corn Festival in 1637, where Pilgrims entered the festival and massacred hundreds of men, women, and children from the Pequot tribe, took their food, and called it a Thanksgiving.

The first National Day of Mourning demonstration was held in 1970 after the then-leader of the Wampagnoag tribe Frank “Wamsutta” James’ speaking invitation was rescinded from a Massachusetts Thanksgiving Day celebration after he refused to be silent about the past treatment of his people. Instead, James delivered a speech on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts next to Ousamequin’s statue, where he described Indigenous peoples’ perspectives on the holiday.

This year, the event began with a prayer service at 12:00pm, followed by speeches from members of the Indigenous community and a march, according to a report by Maine Public Radio. Kisha James, a member of the community who to Boston’s public radio station WBUR-FM in 2020, said that many Indigenous people also fast from sundown the night before to sundown the day-of to remember the hardship and genocide their ancestors faced.

“Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands and the erasure of Native cultures,” the UAINE said in a statement on their website about this year’s event. “It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection, as well as a protest against the racism and oppression that Indigenous people continue to experience worldwide.”

In addition to the physical gathering, there is a livestream via YouTube and Facebook so that interested viewers around the country can tune in.

A team of physicists from Sofia University in Bulgaria say that wormholes, which are hypothetical tunnels linking one part of the universe to another, might be hiding in plain sight — in the form of black holes, New Scientist reports.

Black holes have long puzzled scientists, gobbling up matter and never letting it escape.

But where does all of this matter go? Physicists have long toyed with the idea that these black holes could be leading to “white holes,” or wells that spew out streams of particles and radiation.

These two ends could together form a wormhole, or an Einstein-Rosen bridge to be specific, which some physicists believe could stretch any amount of time and space, a tantalizing theory that could rewrite the laws of spacetime as we understand them today.

Now, the researchers suggest that the “throat” of a wormhole could look very similar to previously discovered black holes, like the monster Sagittarius A* which is believed to be lurking at the center of our galaxy.

“Ten years ago, wormholes were completely in the area of science fiction,” team lead Petya Nedkova at Sofia University told New Scientist. “Now, they are coming forward to the frontiers of science and people are actively searching.”

The team’s newly developed computer model, as detailed in a new paper published in the journal Physical Review D, suggests the radiation emanating from the discs of matter swirling around the edges of wormholes may be near impossible to distinguish from those surrounding a black hole.

In fact, the difference in the amount of light polarization emitted by a black hole and a wormhole, at least according to their model, would be less than four percent.

“With the current observations, you cannot distinguish a black hole or a wormhole — there may be a wormhole there, but we cannot tell the difference,” Nedkova told New Scientist. “So we were looking for something else up there in the sky that could be a way to distinguish black holes from wormholes.”

While Nedkova and her colleagues suggest there may be ways to distinguish between them with observations in the future. For instance, we could look for light that may be spilling in from the other end of the wormhole and emanating out of the black hole in the shape of small rings of light.

But for now, we simply don’t have the technology to make those kinds of direct observations of black holes.

The only way to really tell for sure would be to scan these celestial oddities with an even higher-resolution telescope.

The other option, of course, would be to risk it all by flinging yourself into a black hole.

“If you were nearby, you would find out too late,” Nedkova told the publication. “You’ll get to know the difference when you either die or you pass through.”

READ MORE: How to tell the difference between a regular black hole and a wormhole [New Scientist]

More on wormholes: Astrophysicist Says We May Have Already Observed Wormholes Created by Alien Civilization

The post Objects We Thought Were Black Holes May Actually Be Wormholes, Scientists Say appeared first on Futurism.

In Newtonian physics, space and time had their independent identities, and nobody ever got them mixed up. It was with the theory of relativity, put together in the early 20th century, that talking about space-time became almost unavoidable. In relativity, it’s no longer true that space and time have separate, objective meanings. What really exists is space-time, and slicing it up into space and…

When people argue, a kind of frustration called persuasion fatigue can cloud their judgment and harm relationships