Piotr H. Kosicki

The post SCOTUS and the Catholic Authoritarian Vanguard appeared first on The Nation.

Piotr H. Kosicki

The post SCOTUS and the Catholic Authoritarian Vanguard appeared first on The Nation.

As Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels explained in their foundational exposition of historical materialism and the dialectics of social transformation, a mode of production in crisis does not collapse under the weight of its own malfunction; it has to dismantled and replaced through the self-conscious action of a rising revolutionary class.

The multiplying crises of capitalism have led to internal dysfunction and debilitations that render its operations increasingly out of sync with the needs and basic sustenance of the vast majority of humanity and the rest of the natural world. It is rapidly reaching the limits of its own capacity for self-reproduction, and cannot seem to persist without inducing even greater calamity and instability. As the capitalist system trudges on in this linear trajectory, a cumulative transformation is well underway: where more will have to be sacrificed so that capitalism may live on.

The post The Making of a System in Crisis: the ungovernability of 21st century capitalism appeared first on puntorojo.

The devastating effects of global warming are being felt by billions of people all around the world. Meanwhile, capitalist fat cats are openly downplaying the risk of entire cities being buried beneath the rising oceans as a trifling inconvenience. Like Emperor Nero before them, the rulers of this destructive system are fiddling–this time–as Rome drowns.

To prosper, investors now need a tightrope walker’s surefootedness and a wad of cash, writes Satyajit Das.

An outlook from Uruguay describes how communalists can engage effectively with social movement groups and popular organizations.

From the Usufruct Collective. For earlier writings and a contact form, see https://usufructcollective.wordpress.com/.

What is Communalism?

Communalism is a philosophy and praxis in favor of the means and ends of developing community assemblies with specific kinds of qualifications: those qualifications being practices and processes of horizontality, direct democracy, free association, co-federation mutual aid, and direct action. Horizontality combined with direct democracy means direct collective decision making without ruling classes or ruling strata. Free association means the freedom of, from, and within associations. Co-federation refers to ways of organizing between organizations where policy making power is retained in general assemblies of groups. Mutual aid refers to mutual support and voluntary association to meet people’s needs. Direct action refers to direct activity of collectives and persons more broadly– although usually refers to oppositional politics done by people directly. The above practices are the extension of freedom and self-management of each and all on every scale. Communal assemblies in harmony with communalism have the above features as part of their living practices and processes and enshrine such features in bylaws, constitutions, and structure. Such assemblies are communalist assemblies not in the sense that the assemblies and the members thereof all have the specific ideology of communalism, but in the sense that such assemblies have the minimal qualifiers of what constitutes communalist processes and practices.

What are communal assemblies do and how they function?

Such communal assemblies in harmony with the features of communalism functionally do reconstructive and oppositional politics. Reconstructive politics refers to developing horizontalist and common politics and economics, people powered infrastructure and institutions, mutual aid projects, and other features that should exist according to criteria of freedom of each and all and the means thereof. Oppositional politics refers to opposing hierarchies (institutionalized top-down command obedience), injustice, and arbitrary limits to freedom and using direct action to achieve various liberatory goals. Communal assemblies can create a wide array of sustained mutual aid projects and direct action campaigns. Such communal assemblies pool needs, tools, resources, ideas, abilities, activities, technology, etc. together to achieve common goals through deliberation and collective action. In such assemblies there is open dialogue, a search for agreement, disagreements, alternatives, amendments, questions etc. If full agreement is not reached, then a decision is made through majority vote. In order to be in harmony with communalist practices and processes, any decisions communal assemblies make must be qualified by horizontalist rights and duties, form and content, as well as free association and participatory activity of persons. Such communal assemblies have mandated and recallable participatory councils and delegates that implement various decisions that are made at the communal level by general assemblies. All policy making power resides in the general assemblies. Embedded councils self-manage within the limits of the policy they are mandated by from below. Such embedded delegates and councils are instantly recallable by their respective communal assemblies and co-federations thereof.

In the good place:

In a good society, communal assemblies become forms of horizontal political economic governance. Means of production, fields, factories, and workshops would be communalized, all would have guaranteed rights to common means of production, the means of existence, and the means of direct horizontalist politics. Persons and collectives would have access to the means to develop their various social, philosophical, and artistic activities, aspirations, and hobbies. Necessities and luxuries would be free for all and made abundant. When there is scarcity of luxury goods, there would be new plans to meet needs with scarce luxury goods rationed as needed. Communities would get together to make decentralized and co-federated communal and intercommunal decisions and plans to meet people’s needs within and between communities and to develop common projects, activities, and infrastructure as expressions of participatory communal and inter-communal life. Communal self governance would become a realm of common freedom: participatory activity of each and all within horizontalist bounds and the means thereof.

From here to there:

The process of developing a communalist society is through the strategic prefiguration of communalist institutions and practices via oppositional and reconstructive politics in particular contexts adapted to relevant variables. Such a process consists of meeting people’s needs, opposing hierarchies and injustice, building the kinds of organizations that should exist in the future society by including the features of a good society within the means used to develop such ends. Such general practices would be adapted to contexts and relevant variables to achieve short term, mid term, and long term goals. As communal organizations in harmony with the features of communalism multiply, they can constitute a “third sector” to the capitalist market and the state that can be expanded into confederations and gain legitimacy by meeting needs, solving problems, and developing horizontalist power at the expense of hierarchical power. Overtime, this communal sector would develop itself and overthrow hierarchical institutions and institute libertarian communism.

Reasons why:

Such communal assemblies can engage in and assist oppositional and reconstructive politics in spheres such as extraction, reproduction of daily life, production, distribution, consumption, community life, and intercommunal life. This makes them flexible and adaptable to specific contexts and provides a non-reductionist approach to where revolutionary activity can take place. Additionally, such communal assemblies are needed for self-management in every sphere and is the extension of the self-management of each and all in the community sphere. For such ends and processes to be developed they need to be prefigured– that is developed in such a way where the ends are as much as possible contained within the means, where groups with communalist form and content continue to develop and multiply such form and content. Additionally communal assemblies can easily assist various groups and projects as part of a social movement ecosystem . It is for the above reasons, and others, that communal assemblies are “keystone organizations” to be developed (to use an ecological metaphor).

Especifismo and Ideologically and Theoretically Specific Libertarian Communist groups:

What is especifismo?

The major purpose of such ideologically and theoretically specific libertarian communist groups is to do social insertion: that is to create and participate in social movements, social movement groups, and popular organizations in and out of the workplace (such as community assemblies, unions, tenants’ unions, issue specific social movements, etc) in such a way where members of such ideologically and theoretically specific libertarian communist groups help to develop and assist liberatory processes and practices within social movements and popular organizations. Within social movements and popular organizations, members of especifismo groups advocate for practices of self-organization, direct democracy, federalism, direct action, mutual aid, class struggle, and opposition to hierarchy more broadly. Such libertarian practices are spread within social movements and popular organizations through deliberation, persuasion, and demonstration. Such practices can be developed in new organizations starting from scratch or through joining already existing organizations and helping to cultivate the already existing libertarian thrust of such groups towards their own goals. The goal of social insertion is to spread such libertarian socialist processes and practices and not to get any particular person or group to proclaim any specific ideology– however in the process of spreading liberatory practices and giving reasons for them various corresponding theories will likely spread to people and become more generalized.

Especifismo groups are places for like minded organizers and militants to produce, reproduce, deliberate and strategize about theory and practice more broadly. Especifismo groups engage in political education and propagation of libertarian communist theory and practices. These groups require a high degree of collective responsibility on the part of participants. Specifics in regards to especifismo groups and how they function can be found in FARJ’s “Social Anarchism and Organization”.

Why especifismo?

If libertarian socialists merely organize with libertarian socialists, then they will lose contact with the broader population they need to be reaching. If libertarian socialists merely join social movements without advocating various libertarian socialist practices that can be used, then social movements can easily drift into being susceptible to reformist, unstrategic, liberal, and leninist tendencies and opportunists. If libertarian socialists merely join social movements and try to spread ideas and practices in mere individual ways, they will be far less successful than a well thought out coordinated effort. And if ideologically and theoretically specific libertarian socialist groups try to control social movements and popular organizations from the top down, then such specific groups sacrifice their own principles and will reproduce hierarchical organizing. In contrast to authoritarian vanguardist conceptions, especifismo groups and especifists put their activity towards the self-organization of movements and organizations.

Differences between especifismo and other organizational dualisms:

Especifismo is a tendency initially developed by FAU in Uruguay building off of already existing organizational dualist tendencies within anarchism. Especifismo is a living praxis being developed on multiple continents. Especifismo is distinct from other kinds of organizational dualism in its advocacy for and conception of strategic unity rather than mere tactical unity, through its polished conception and strategy of social insertion, and through having a broader conception of groups to organize with and relate to far beyond radical unions.

Communalist Especifismo:

Communalist especifists combine both communalism and especifismo: That is they are in favor of communal assemblies as popular organizations before, during, and after revolutions and they are in favor of joining especifismo groups to help develop such communalist assemblies as well as other kinds of liberatory groups. The two praxes combine through social insertion in relation to community assemblies: both through starting communal assemblies and helping to develop already existing community associations into ones that use a cluster of liberatory practices. Additionally such communalist social insertion means developing community assemblies within or connected to social movements to help achieve the goals of social movements when that makes sense in specific contexts.

Part of what distinguishes communalist especifismo from classical communalism is the emphasis upon the distinction and need (or more moderately desirability) for both theoretically specific libertarian socialist organizations and popular organizations as well as social insertion for purposes of revolutionary social change. Without the distinction between ideologically and theoretically specific groups and popular organizations, it is quite possible to form a group that tries to do the functions of both yet functionally does not fulfill the functions and aspirations of either (a problem some organizational dualist tendencies are consciously responding to). Part of what distinguishes communalist especifismo from especifismo is agreeing with the most salient features of communalism such as the notion that communal assemblies in harmony with the features of communalism are “keystone organizations” to be developed before, during, and after revolutions. Such a communalist orientation is not essential to especifismo despite overlap between especifismo groups and communal assemblies. Communalist especifismo does not and should not mean a reduction of especifismo groups to only interfacing communal assemblies: merely an additional emphasis upon communal assemblies as keystone organizations to be prefigured and developed before, during, and after revolutions (for ethical and strategic reasons). A communalist especifismo group would be composed of people who agree with especifismo and communalism and who are actively engaged in trying to develop such a revolutionary project.

Endnotes:

Bookchin, Murray. Social Ecology and Communalism. AK Press, 2007.

FARJ. Social Anarchism and Organisation , 2008.

Weaver, Adam. “Especifismo: The Anarchist Praxis of Building Popular Movements and Revolutionary Organization in South America .” libcom.org, 2006. https://libcom.org/library/especifismo-anarchist-praxis-building-popular-movements-revolutionary-organization-south.

Usufruct Collective. Communalist Especifism. 2019

The post Communalism and Especifismo appeared first on Institute for Social Ecology.

We speak with pioneering scholar and activist Kimberlé Crenshaw about the growing Republican effort to ban critical race theory — an academic field that conservatives have invoked as a catchall phrase to censor a variety of curriculums focusing on antiracism, sex and gender. Crenshaw has launched what she calls a “counterterrorism offensive” against the Republican efforts with a “summer school” inspired by the Freedom Summer movement of the 1960s. The school debunks the “bothsidesism” debate Crenshaw says is upheld by mainstream media, and highlights the importance of critical race theory in building a multiracial democracy. “There’s no daylight between the protection of our democracy and the protection of antiracism,” says Crenshaw.

When I first arrived in South Africa, in 2009, it still felt as if a storm had just swept through. For most of the 20th century, the country was the world’s most fastidiously organized white-supremacist state. And then, in one election, in 1994, it became the first modern nation where people of color who’d been dispossessed for centuries would make the laws, run the economy, write the news, decide what history to teach—and wield political dominance over a substantial white minority. Unlike in other postcolonial African countries, white South Africans—about 15 percent of the population—were suddenly governed by the people whom they and their forebears had oppressed.

Over the decade I lived in South Africa, I became fascinated by this white minority, particularly its members who considered themselves progressive. They reminded me of my liberal peers in America, who had an apparently self-assured enthusiasm about the coming of a so-called majority-minority nation. As with white South Africans who had celebrated the end of apartheid, their enthusiasm often belied, just beneath the surface, a striking degree of fear, bewilderment, disillusionment, and dread.

The story of white settlement in South Africa has uncanny parallels with U.S. history. In the late 1600s, a group of predominantly Dutch-descended settlers started arriving by boat from Europe. After a century and a half working on semifeudal wine estates under the command of the Dutch and then the British, a band of them, now known as Afrikaners, decided to assert a new pioneer identity. Thousands set out for the interior in ox wagons. Their guiding dream, they declared in a newspaper-printed manifesto, was to uphold “the just principles of liberty.” On the frontier, they set up a host of small, independent republics with constitutions modeled on America’s. Many believed that they had been sent by God to tame a new world—Africa’s own version of Manifest Destiny.

After taking the reins of the government of South Africa—which amalgamated the Afrikaner republics and several British colonies—in the mid-20th century, white leaders began to legalize segregation under the term apartheid. They sent emissaries to the U.S. to study the Jim Crow South, which they used as a model for their own regime. Hermann Giliomee, a historian of the Afrikaners, told me that when the South Africans saw Alabama’s segregated buses and colleges, “they thought to themselves, Eureka!”

Apartheid completely partitioned South Africa by race and reserved the best jobs and land for white people. The system endured until the 1990s, when, thanks to a sustained effort by the African National Congress (ANC), it crumbled. Sometimes I like to tell people that South Africa, very loosely, collapses hundreds of years of American history—from the antebellum period, through the end of Jim Crow, and well into our future—into about 50. For being such a tragedy, apartheid seemed to have a miraculous conclusion—a rapid and peaceful end that spared even the defeated oppressors.

Unexpectedly, white people benefited materially from the end of apartheid. Thanks in part to the lifting of foreign sanctions, the average income of white households increased 15 percent during Nelson Mandela’s presidency, far more than Black incomes did. White businesspeople started to export wine and $10,000 ostrich-leather sofas to Europe, and white-run safari lodges welcomed a flood of new tourists.

White South Africans were rewarded in other ways, too. They no longer had to serve in a military that hunted Black-liberation groups. In the run-up to apartheid’s end, strict censorship laws were dropped, and they could finally listen to the likes of Bob Dylan on the radio. And for the many white progressives who had opposed apartheid, South African society moved far closer to their ideal of racial equality.

[Read: South Africa confronts a legacy of apartheid]

Yet these progressives’ response to the end of apartheid was ambivalent. Contemplating South Africa after apartheid, an Economist correspondent observed that “the lives of many whites exude sadness.” The phenomenon perplexed him. In so many ways, white life remained more or less untouched, or had even improved. Despite apartheid’s horrors—and the regime’s violence against those who worked to dismantle it—the ANC encouraged an attitude of forgiveness. It left statues of Afrikaner heroes standing and helped institute the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which granted amnesty to some perpetrators of apartheid-era political crimes.

But as time wore on, even wealthy white South Africans began to radiate a degree of fear and frustration that did not match any simple economic analysis of their situation. A startling number of formerly anti-apartheid white people began to voice bitter criticisms of post-apartheid society. An Afrikaner poet who did prison time under apartheid for aiding the Black-liberation cause wrote an essay denouncing the new Black-led country as “a sewer of betrayed expectations and thievery, fear and unbridled greed.”

What accounted for this disillusionment? Many white South Africans told me that Black forgiveness felt like a slap on the face. By not acting toward you as you acted toward us, we’re showing you up, white South Africans seemed to hear. You’ll owe us a debt of gratitude forever.

White people rarely articulated these feelings publicly. But in private, with friends and acquaintances, I encountered them over and over. One white friend and former anti-apartheid activist (who didn’t want to be identified in order to talk freely) told me that after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission publicized much of what Black South Africans had faced under apartheid, she felt humiliated to recall what she and her friends had once considered resistance: gestures like having a warm exchange with a Black maid or skipping class to join an anti-apartheid march.

She said that sense of embarrassment made her shy away from politics, as did the slow-dawning recognition that Black people—many of whom had worked in white people’s houses under apartheid—knew much more about the lives of white people than white people knew about Black lives. My friend had never even seen the inside of a Black person’s home.

Not infrequently, white South Africans who identified as progressive confessed to me that they wanted to withdraw from public life because they felt they couldn’t speak the truth about what they did see. Many felt that only Black people could point out certain realities—for example, that Black-majority rule hasn’t reduced economic inequality since apartheid or that half of Black people under 35 are unemployed. If a white person expressed too much pessimism, they could be considered demeaning. Too much optimism, and they could be accused of neglecting enduring racial inequalities. The window they had to exist in, intellectually, could appear so narrow as not to exist.

At a Johannesburg party I went to, two voluble white women who called themselves “socialists” started to debate with me about the U.S. As Africans, they wanted me to know that American greatness was a sham and American-style consumerism was a pox on Africa. The party’s lone Black guest—a young woman—crouched silently in front of the fireplace, pushing embers around with a poker.

Suddenly, she spoke. The two white women misunderstood America, she said, without rancor. She had gone to high school in California. And, yes, there was racism. But she found the country much less racist than South Africa, and exciting—a land of opportunity.

The party went silent. The white women’s lips were pressed into half-gracious, half-bitter twists. They had been shamed, and they wanted to argue. But their stated values—always to foreground historically marginalized voices—meant they had to take the Black guest’s word for it. Shortly afterward, they left.

A pair of German tourists once told me about stopping at a remote South African bed-and-breakfast and telling the owner they were going to take a walk. She informed them that it was too dangerous. Politely, the tourists said they had checked the crime stats ahead of their trip and felt it was safe. Outsiders can’t understand, the owner whispered back. She never walked anywhere, not even to her car, without a pair of metal knitting needles stuffed into her pocket in case she had to poke out an assailant’s eye. The Germans got the impression that she relished reporting this detail.

Concerns about crime dominated the news in the years following apartheid. But the rates of violent crime were only half as high by the end of the 1990s as they had been before apartheid ended. In 2016, Mark Shaw and Anine Kriegler, two leading South African criminologists, wondered, “How is it that [the] huge reduction in fatal violence over the last two decades isn’t something we rejoice over, talk about, or even seem aware of?” They noticed stark discrepancies between crime’s actual and perceived prevalence. For instance, when white South Africans answered a survey about the crimes they’d experienced, their responses contradicted what they’d reported to police stations. To the police, they reported carjackings at double the rate they reported home invasions. But they told the pollsters they’d experienced home invasions twice as often as they’d had their cars jacked.

Carjacking is an easier crime to fake for insurance fraud, and therefore might be overreported. But the disparity was so stark that it suggested another explanation: A number of white South Africans had a memory of someone breaking into their homes when it never happened.

The journalist Mark Gevisser has called this fear of home invasion by Black burglars “Mau Mau anxiety,” after the guerrilla movement that helped drive white colonists out of Kenya in the 1950s. He wrote that this fear lurks even “in a bleeding-heart liberal like myself.”

[From the April 1964 issue: British South Africa]

Giliomee, the historian, told me he thought that what dogged white progressives after apartheid ended was less a concern for physical safety than a feeling of irrelevance. Under apartheid, many of them felt they belonged to a vanguard. One of Giliomee’s friends, a liberal white politician, left a secret 1987 meeting about a transition to Black-majority rule believing that he and the prominent ANC leader Thabo Mbeki were “best friends.” He expected the aftermath of apartheid to be an exciting time, full of the same thrilling work he had done to help build a democratic, multiracial future for the country.

Once Black leaders secured political power, though, they didn’t have to rely as much on white allies. When Mbeki became Mandela’s deputy president, he wouldn’t return the white liberal’s calls. The politician sent policy proposals and got no reply. After apartheid, the friend “started drinking heavily,” Giliomee said. “He drank himself to death.”

This was an extreme case. But a wide range of white South Africans I met felt a sense of alienation after apartheid. On the radio, I often heard an Afrikaans pop song with the lyric “I’m in love with my country, but does my country still love me?” It expressed an anxiety I noticed frequently: Do we still belong here?

In 2006, a group of Afrikaners founded an NGO called AfriForum to respond to these insecurities. The NGO gives its members the subtle but pervasive sense that a white-friendly South African ministate already exists, in which its trendy headquarters—home to multiple radio broadcasts, a publishing house, and a private Afrikaans-language college—serves as the alt-capital. Dues-paying members get access to lawyers who pursue claims against a government program that increases Black ownership stakes in large corporations. They can submit complaints to a system of private prosecutors. For those anxious about home invasion, an app features a “panic button” that dispatches private ambulances.

When I visited AfriForum’s offices in 2016, I was met by Flip Buys, one of the NGO’s founders. In the early 1990s, he and his friends feared Black rule, he told me. Before Mandela’s election, he remembered thinking, “They [Black leaders] have made compromises in order to get power. But after they’ve consolidated power, they will use it to pursue their interests.”

But Buys also felt shamed because he was white. He and his college friends, who wanted to become academics, felt embarrassed to identify themselves as white South Africans when they attended international conferences. Europeans and Americans subtly kept their distance.

Buys found unexpected refuge in the ideas of the sociologist Manuel Castells, who argued that progressives had a duty of care for “Fourth World” groups that lack the protection of their own state. Castells used the term to refer to marginalized peoples such as the Australian Aborigines. “But what if Afrikaners are such a community?” Buys recalled thinking, in a moment of revelation. “I wanted to fight for Afrikaners, but I came to think of myself as a ‘liberal internationalist,’ not a white racist,” Buys told me. “I found such inspiration from the struggles of the Catalonians and the Basques. Even Tibet.”

One of his first projects after co-founding AfriForum was to send a mission to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights arguing that Afrikaners deserved protected status as an endangered ethnic minority. “As a discredited minority, I think we have to fight extra hard for our rights,” he said. “Some people think nothing ever changes, and that a group of people who once held power will always be empowered.” His idea found mass appeal. By 2016, nearly one-quarter of Afrikaners were paying AfriForum members.

[Lawrence Glickman: 3 tropes of white victimhood]

On my tour of the organization’s headquarters, I met a young woman responsible for posting frightening security-camera videos of home invasions to social media. “I sought work with AfriForum because I consider myself a liberal and an environmentalist,” she told me cheerfully. She mentioned an AfriForum initiative to save threatened hippos. A Martin Luther King quote was printed on the office wall, and she pointed to it. “King also fought for a people without much political representation … That’s why I consider him one of my most important forebears and heroes.”

But she also said she hoped Afrikaners would seize back political administration from the Black-led government, because “everything is falling apart.” The Afrikaners, she said, were “naturally good” at management. “South Africa’s environment is very unique. God intended us to look after it.”

Buys told me that the Afrikaners “just want benign neglect” from Black people. Yet AfriForum is unable to resist provocations. The organization frequently sues the ANC government over such issues as white South Africans’ right to display the old apartheid-era flag.

I couldn’t tell if the AfriForum leaders believed their own messaging. Sometimes I felt as if I saw a wink forming in the skin around their eyes. They seemed to relish Black people’s bafflement and criticism. The more contempt the better: If the AfriForum’s provocations got its executives treated badly, they could claim equal status as victims.

This kind of goading could be cruel. “For those claiming [that the] legacy of colonialism was ONLY negative,” a top white South African politician tweeted a few years ago, “think of our independent judiciary, transport infrastructure, piped water etc. Would we have [any of that] without colonial influence?”

“You mean to say that, without white people, we would be nothing?” a Black commenter replied.

The politician would not stop. She doggedly pursued critics until a respondent lashed out, saying he didn’t want to kill white people just yet. Then the politician triumphantly declared that she’d been justified all along in thinking Black people someday intended to take revenge on her.

Nobody “likes to play the victim like white South Africans,” one of the young Black women I know best, the academic Malaika Mahlatsi, told me. She said she believed that “deep down, there is no way” that the vast majority of white people “don’t know what they did was savage. But for them to admit that is too heavy.”

Sometimes I wondered: Why was it so heavy? Why did admitting past sins seem to become harder even as they receded into history? The question began to feel urgent as I started to see a similar phenomenon back home in America.

In South Africa I often felt I was looking at America in a funhouse mirror, with certain emerging features magnified so I could see them more clearly. I saw how progressives could feel grief about being canceled, sneered at, or sidelined—just as their society comes to look more like what they had argued for.

I also saw historically dominant people—especially those who criticized their own authority—become fully aware of their dominance only as it started to ebb. Many white South Africans told me that during apartheid they’d sincerely believed that their country was, demographically speaking, majority white.

I saw how they might need to start telling themselves, and others, that people of color were letting the country down. This belief helped justify the panoply of privileges that many white people were unaware they even had under apartheid, when they had compared themselves to other white people instead of the Black majority whose experiences were partially hidden.

If white progressives recognized any good in post-apartheid South Africa, they would also have to acknowledge that they—who frequently live more comfortably than they could on the same salary anywhere else on Earth—were still making out like bandits. One white friend told me that he and his wife felt “deep down” that white people in South Africa had “got[ten] away with hundreds of years of injustice.”

Perhaps the strangest thing I saw was how deeply troubled white South Africans were by this feeling—that white people had never faced a full reckoning for apartheid. Apartheid-era white elites had justified white domination by saying that, without their rule, Black people would take revenge on them or ruin the country. When widespread revenge and ruin never came, many white people felt forced to fabricate it; otherwise, white dominance became all the more shameful—not only to apartheid’s proponents but even to anti-apartheid progressives, who had inevitably benefited from a regime that comprehensively promoted white interests.

The Afrikaner journalist Rian Malan, who opposed apartheid, has written that, by most measures, its aftermath went better than almost any white person could have imagined. But, as with most white progressives, his experience of post-1994 South Africa has been complicated.

A few years after the end of apartheid, he moved to an upscale Cape Town neighborhood. Most mornings, he drank macchiatos at an upscale seaside café—the kind of cosmopolitan place that, thanks to sanctions, had hardly existed under apartheid. “The sea is warm and the figs are ripe,” he wrote. He also described this existence as “unbearable.”

He just couldn’t forgive Black people for forgiving him. Paradoxically, being left undisturbed served as an ever-present reminder of his guilt, of how wrongly he had treated his maid and other Black people under apartheid. “The Bible was right about a thing or two,” he wrote. “It is infinitely worse to receive than to give, especially if … the gift is mercy.”

This article has been excerpted from Eve Fairbanks’s new book, The Inheritors: An Intimate Portrait of South Africa’s Racial Reckoning.

News / 19th July 2022

Wildfires and heatwaves wreaking havoc across swathes of the globe show humanity facing “collective suicide”, the UN secretary general has warned, as governments around the world scramble to protect people from the impacts of extreme heat.

“Don’t sweat the small stuff” is actually great advice.

To say that our plates are full would be an understatement. The reality of contemporary living requires our attention and efforts be divided between demanding jobs, essential familial caregiving, replenishing social gatherings, and fulfilling political and community engagements — not to mention any hobbies or creative endeavors. According to Pew Research Center surveys, 60 percent of adults said they were sometimes too busy to enjoy life. Busy-ness, unsurprisingly, intensifies once you have kids: 74 percent of parents with children under the age of 18 reported being too busy to enjoy life.

There are a number of reasons people pack their schedules. Hustle culture has normalized always-on, blind ambition; society still expects women to balance the pressures of work and home life; people pleasers have difficulty saying no. Existential fears of climate change, political turmoil, and economic strain perhaps weigh less heavily when you’re distracted by a never-ending to-do list.

“We’re socialized,” says licensed marriage and family therapist Mona Eshaiker, “to care and to provide and to help. If we do it without boundaries and without limits, we’re going to be burnt out and then we’re not doing anybody any favors.”

The myth of perfectionism keeps many in a cycle of feeding into external pressures: the illusion of “having it all,” gleaning self-worth from the validation of others. Of course, it is worthy and noble to be passionate about people and causes you care about. It’s also easy to fall into the trap of attempting too much in the pursuit of trying to have it all.

Instead of being everything to everyone and everything all the time, what would life look like if you cared a little less? “What if,” says Deborah J. Cohan, professor of sociology at University of South Carolina Beaufort and author of Welcome to Wherever We Are: A Memoir of Family, Caregiving, and Redemption, “we aim for good enough?”

Much of our desire to take on extra tasks and responsibilities comes from a sense of obligation to others, experts agree, but even that can be self-directed. “Seventy-five percent of the time, the guilt is coming from inside the house,” says Sarah Knight, author of a series of “No Fucks Given” guides, including The Life-Changing Magic of Not Giving a Fuck and Get Your Shit Together. “You are making it up in your own head.”

No one’s expectations of you are as high as your self-imposed expectations. If you feel guilty about bringing store-bought pasta salad to a barbecue instead of a homemade dish, the only person who is going to shame you for that is yourself. While turning down additional responsibilities at work because your plate is already full can feel like you’re dropping the ball, most likely the asker will quickly find a volunteer who is more than eager to take on the extra project. “Nobody’s mad,” Eshaiker says. “People don’t want us to feel pressured, either, or stressed.”

Before making a decision about whether to care a little less or to turn down a favor that’s asked of you, Knight says to ask yourself whether saying no would have a negative effect or comes from a mean-spirited place. “RSVPing no to a party is not an objectively bad thing,” she says. “Saying yes and then canceling at the last minute — not because you legitimately got food poisoning but because you never really wanted to go … that’s something you can feel guilty about. Don’t do that.”

Caring less doesn’t mean negligence. To care less about inconsequential matters, you need to zero in on what is worth caring for. Consider taking stock of to-do list items and obligations and asking if these responsibilities make your day feel more spacious or more confined, Cohan suggests. Does it nourish your sense of creativity? Is it the best use of your time and talent? Does it make you feel exhausted? Do you want to spend your time and energy on this?

Eshaiker says to ask yourself, “Why do I care?” about various aspects of life. “Is this something that is aligned with my values?” she says. “Is this something that I believe is helpful for myself and for humanity?” If you feel compelled to care about something out of fear or wanting to be accepted by others, it may not be worth placing emphasis on it.

Of course, there are nonnegotiable obligations — the basic functions of your job, caring for children, paying bills — which may not be life-affirming but require attention nonetheless. Once you define these true commitments, you can “divorce yourself from the concept of ‘I have to do it,’” Knight says, when it comes to other tasks you thought essential, like waking up at 5 am to do laundry when doing it after work will suffice.

When Knight quit her job as a book editor in 2015, she realized what Marie Kondo advocated for in terms of physical organization, Knight was doing to her brain: eliminating the habits and people that no longer sparked joy. Think about the instances you really didn’t enjoy or that made your life more difficult — such as attending a casual friend’s bachelor party when you really wanted to catch up on reading instead. When similar opportunities arise, you can confidently turn down things you know won’t serve you, Cohan says.

Just because you excel at something — be it creating detailed spreadsheets or making complicated desserts for dinner parties — doesn’t mean you have to agree to it every time you’re asked or volunteer to do it to impress others. “Even though I know I can make the really great, complicated cake — I’ve made them, I’m good at it,” Cohan says. “But it doesn’t mean I have to do it because maybe it’s not the best use of my Saturday.”

In the thick of the daily grind, minute conflicts can often get blown out of proportion: Your kid didn’t do the dishes when you asked, you were 10 minutes late to a doctor’s appointment, a friend forgot she was supposed to bring snacks to game night. People are quick to ascribe meaning to these ordinary events — jumping to conclusions and thinking a friend is inconsiderate, say, by not answering your phone call in the middle of a workday. If you pause and take a step back, none of these things actually have a profound bearing on your life, Eshaiker says. Say you find yourself constantly wrapped up in drama — consider asking yourself why you’re stimulated by the excitement of conflict or which big life decisions you’re trying to distract from. “Sometimes not reacting is the best thing to do,” she says.

The same thing goes for work. Many people’s value and self-worth is intrinsically tied to their jobs. But if you zoom out and consider who you are outside of your job, you may realize other areas of life where you might be lacking, like spending quality time with family or practicing art or music — parts of life you decided you want to prioritize.

When you’re constantly stressed and in a fight-or-flight state of mind, finding this perspective is difficult, Eshaiker continues. Every minor issue feels like an urgent fire needing to be extinguished. Instead of making mountains out of molehills, Eshaiker suggests getting to the root of why you’re negatively fixated on the outfit your partner decided to wear to a wedding, for example. “Is it because I want my partner to present well in public because then I want to get approval from others?” she says. “But that has nothing to do with my ultimate values and my goals. Again, you’re just giving up your power to other people if it’s about external validation in some way.” Relinquishing the perceived influence onlookers have over your life frees up space for you to care about things that actually matter.

In order to get to a place where you’re able to look at the bigger picture, Eshaiker says you need to prioritize rest and centering yourself, which looks different for everyone: meditation, taking a walk, no email before bed.

Once you’ve defined what is and isn’t worth your time, you’ve got to set, and express, boundaries. Boundary-setting can seem like an amorphous buzzword, but it isn’t as simple as learning how to say no. According to Knight, boundary-setting is outlining what you need and what is important to you and protecting those desires. This can be as simple as writing a list of things that make you happy (reading, going to the gym, cooking, a life with minimal stress), allow you to earn a living (your job), and other areas of importance (friends, family, getting a good night’s sleep).

Then ask yourself what you need to do to protect these things. Maybe you decline invites to weeknight social activities in order to prioritize good sleep. Perhaps you need to spend less time with a friend who invites conflict.

“If they really sit down and think about it for five minutes, they’re gonna realize the biggest, unwanted drain on their time, energy, and money,” Knight says. “It could be a relationship in their life — it could be a parent, it could be a friend, someone they’re dating — and that the boundary that you need to set to preserve your time, energy, money, sanity, mental health, is to basically fence that person outside of all of that.”

Another way to set boundaries, Knight says, is to ask yourself, “What’s wrong with my life?” and then to identify why. For example, you might feel depleted after hanging out with a certain friend. Why? Are you giving more than they’re willing to reciprocate? Do you no longer have much in common? “It all comes down to identifying what you want, the need, what’s important to you, and then what you have to do to protect those things,” Knight says.

Time is finite and shouldn’t be dictated by others or how you believe others to perceive you. If caring a little less means not immediately volunteering to lead every new initiative at work or skipping a few PTA meetings, you’re saving time and energy for the things that matter.

“It’s like trimming the fat,” Cohan says, “off of a day or a week.”

Even Better is here to offer deeply sourced, actionable advice for helping you live a better life. Do you have a question on money and work; friends, family, and community; or personal growth and health? Send us your question by filling out this form. We might turn it into a story.

In the spring of 2012, Blake Masters, who was in his final year at Stanford Law, sat in on a computer science class taught by Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of PayPal. During a lecture titled “Founder as Victim, Founder as God,” Thiel argued a kinglike leader was essential to innovation. “A startup is basically structured as a monarchy,” he explained. “We don’t call it that, of course. That would seem weirdly outdated, and anything that’s not democracy makes people uncomfortable.”

Afterward, Masters tweeted that the lecture was the best 90 minutes he’d ever spent in a classroom and linked to the exhaustive notes he’d been taking on Thiel’s course. For months, everyone from tech bros to New York Times columnist David Brooks headed to Masters’ Tumblr to read them. It was heady stuff for a CrossFit-obsessed libertarian described by a law school classmate as being “notable for not being notable.”

[Related: 6 Revealing Moments From Our Profile of GOP Senate Candidate Blake Masters]

Masters was the perfect Thiel protégé. Both men attended Stanford and Stanford Law as proud iconoclasts who chafed at limits on their freedom. But while Thiel alienated dormmates by performatively downing vitamins as they nursed hangovers, Masters had the social skills to make friends in environments as ideologically hostile as the vegetarian co-op he lived in at Stanford. He had the ideal résumé to help a famously awkward billionaire popularize his unorthodox views.

Blake Masters speaking with attendees at the “Rally to Protect Our Elections” hosted by Turning Point Action at Arizona Federal Theatre in Phoenix.

Gage Skidmore/The Star News Network

Masters would never leave Thiel’s orbit. After finishing law school in 2012, Masters worked on a legal research startup with funding from his former teacher, co-authored a bestseller with Thiel based on the notes he’d taken from that class, and served as Thiel’s chief of staff and the president of his charitable foundation. Now, Masters is running for US Senate in Arizona with more than $13 million from Thiel behind him. If Masters wins his August primary, he will face Mark Kelly, the former astronaut and husband of former Congress member Gabby Giffords, in one of several races expected to decide which party controls the Senate.

Years ago, the two men’s focus on electoral politics would have seemed unlikely. Earlier in his career, Thiel wrote about creating floating colonies in the ocean, while Masters told people not to vote. Since then, both have had changes of heart about means, not ends. Instead of escaping state control, Masters and Thiel now hope to use its power to solidify the dominance of the founder class and end the technological stagnation they believe could lead to humanity’s extinction. To do so, they are willing to move fast and break things. But instead of disrupting taxi companies or hotels, American democracy is in their sights. A decade after his startup lectures, there should no longer be any doubt that Thiel’s sympathy for authoritarianism extends well beyond the private sector.

Thiel and Masters are willing to move fast and break things. But instead of disrupting taxi companies or hotels, they’ve got American democracy in their sights.

So he’s spending big to bend the American right to his will. He has also put at least $15 million behind Ohio Senate candidate JD Vance—another former employee, best known for his memoir Hillbilly Elegy—and helped arrange the Trump endorsement that secured Vance’s primary victory. In total, Thiel is supporting more than a dozen Republican candidates, most of whom have disputed the results of the 2020 election. And while he may soon have three senators whose rise he has helped fund—Vance, Masters, and Sen. Josh Hawley, another right-wing Stanford grad—it is Masters who would allow Thiel to effectively have a seat of his own.

Beginning in March, I sent repeated interview requests to Masters, who never replied. Last week, I sent him an extensive list of 24 fact-checking questions, which he also ignored. Thiel also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Arizona voters who want to comprehend just how unusual Masters is must understand the full pantheon of his influences. They include Curtis Yarvin, who describes himself as America’s foremost absolute monarchist blogger; Murray Rothbard, the reactionary economist who suggested libertarians use right-wing populism to push their agenda; and Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, whom Masters has praised (with caveats). Another favorite is Lee Kuan Yew, the late dictator of Singapore who oversaw a miraculous economic transformation while crushing the civil liberties of those who stood in the way.

But no one is as influential as Thiel, who confessed in a 2009 essay, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” He went on to warn that the “fate of our world may depend on the effort of a single person who builds or propagates the machinery of freedom that makes the world safe for capitalism.”

Thiel is setting himself up to be that builder. Masters is one of his tools.

In late April, Masters attended a candidate forum in the ballroom of Scottsdale’s Gainey Ranch Golf Club, a 27-hole oasis located on what was once an Arabian horse farm. Wearing a slim-cut navy suit, the 6-foot-3 former basketball player could have passed for a wealthy son visiting any of the prim seniors attending the event. The event’s emcee was a bald man whose LinkedIn profile mentions service in an “anti-terrorism” unit in Rhodesia’s white nationalist regime. To win, Masters would have to convince a primary electorate that skews white and geriatric that a thirtysomething who’d spent most of his adult life in California was the voice of Arizona Trumpism.

After dispensing with the requisite autobiography—raised in Tucson, married to his high school sweetheart, the father of three young boys—he pivoted to the doomsaying that has become his signature campaign spiel. “Conservatism can’t beat progressivism going the speed limit. You got to get people in there who know what time it is, who are going to play offense, because then and only then will we have a chance to save this, the greatest country in the history of the world,” Masters can be heard saying in a recording of the event. “Put me in in August and I guarantee you I will beat Mark Kelly by five points. Imagine me debating him as you’re listening to us tonight.” With that, it was time for the audience’s questions.

Asked about Kelly, Masters responded sarcastically. “‘Oh, I’m an astronaut. Have you heard I’m an astronaut?’” Masters said, imitating the senator. “‘You know, when I’m on the space station and I look at that big blue ball I realize we’re all in it together.’ And it’s like, ‘Shut up, Mark.’” The punchline had the crowd laughing. Such swaggering contempt is typical Masters, who speaks with the self-confidence of a man who has always considered himself to be exceptional and is unsurprised that the world agreed.

Masters speaks with the self-confidence of a man who has always considered himself to be exceptional and is unsurprised that the world agreed.

Over the course of the Q&A, Masters said he backed impeaching Joe Biden over his border policy, attacked generals for being too woke, and warned that Social Security and Medicare would disappear before his fellow millennials became eligible. “Sorry,” he said. “But plan for that now.” (According to the financial disclosure Masters submitted last year, much of his own substantial wealth was held in cryptocurrencies.)

Many of the more than a dozen friends and acquaintances of Masters I’ve spoken with, including the best man at his wedding, have been shocked to see the transformation of someone who used to consider himself an open-borders libertarian turn into an America First nationalist whom Tucker Carlson calls “the future of the Republican Party.” “He was not a shitty, hateful person,” says a former college roommate. “He was a misinformed libertarian white 20-year-old. But honestly, they were a dime a dozen at Stanford.” But even as a young man, there were signs that Masters would be almost uniquely suited to fall under the sway of an icon like Peter Thiel.

When Masters was 4 years old, his family moved to Tucson and settled in a gated community alongside one of Arizona’s best golf courses. His dad, Scott, had attended the Air Force Academy before joining the nascent software industry. His mom, Marilyn, would go on to run a Kumon tutoring center.

Masters got an early introduction to the progressive pedagogy he now loathes as a second grader in public school. Masters wrote a letter to a local paper stating his opposition to clearing desert land for new houses. His conservative parents saw it as evidence that their son was being indoctrinated with left-wing environmentalism. A couple of years later, they were frustrated when Blake was taught that Christopher Columbus was a racist who murdered Indigenous people.

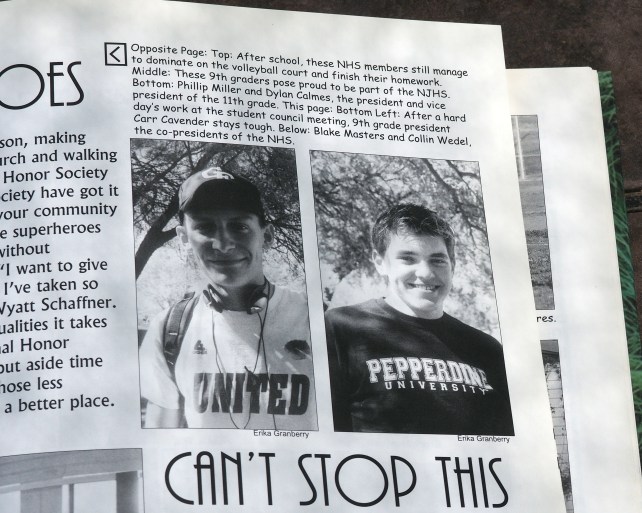

Masters with Green Fields friends Collin Wedel and Noah Gustafson (left to right). Courtesy Noah Gustafson

Masters with Green Fields friends Collin Wedel and Noah Gustafson (left to right). Courtesy Noah Gustafson

For sixth grade, they enrolled young Blake in Green Fields Country Day School. At its founding in the 1930s, the school sought to merge East Coast elitism with West Coast frontier individualism: Boys lived in cabins, practiced on the shooting range, and were provided their own horses as they prepared for schools like Exeter and Choate. By the time Masters started in the late ’90s, Green Fields was co-ed with about two dozen kids per grade.

As an eighth grader, Masters experienced love at first sight when he met a girl named Catherine Chewning. The feeling was not mutual for a young feminist whose poetry in the Green Fields archives included lines like:

But you stayed hidden

Under a layer of your manhood

And refuse to agree

So I’m done trying to help

I’m leaving you to rot in your conceited mind

There’s no evidence that Catherine was writing about Masters, who she came around to in high school and married in 2012. Catherine now homeschools their three boys, and her family shares a backyard with her mother and stepfather, whose Facebook page is filled with liberal posts. One of the articles he shared last year was headlined “Elite Universities Have Promoted Destructive Republican Leaders.”

Masters and the best man at their wedding, Collin Wedel, also met in middle school, and others considered them the best students at a school full of bright kids. Masters was a popular three-sport athlete; Wedel was a sweet nerd. “You can find people who went to preschool with [Ted Cruz], who are like, ‘Oh, yeah, that guy was always an asshole,’” Wedel says, only slightly exaggerating. “That is not Blake.”

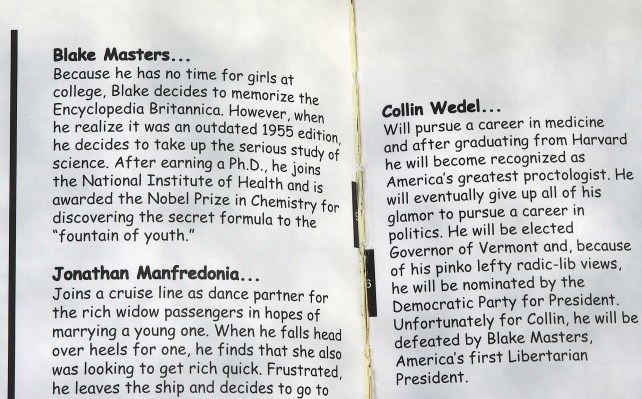

Wedel, a partner at a corporate law firm in California, says that when it came to politics, Masters was mostly interested in libertarian monetary policy, although he also wrote an op-ed for the school paper in favor of the Iraq War. In their senior yearbook, Green Fields faculty made tongue-in-cheek predictions about where the class of 2004 would end up. Wedel, they wrote, was going to be the Democratic nominee for president. “Unfortunately for Collin,” they added, “he will be defeated by Blake Masters, America’s first Libertarian President.”

Predictions from Green Field faculty in Masters and Wedel’s high school yearbook.

In his first year at Stanford, Masters made friends with many progressive students, including two women I’ll call Rebecca and Christina. (Both requested anonymity.) As sophomores, the three of them ended up sharing a room in Columbae, a left-wing vegetarian co-op where decisions were made by consensus. As the year progressed, Rebecca remembers Masters getting more and more militant about his libertarianism. “It became difficult to have meaningful conversations with him,” she says. “We were like, ‘Dude, Ayn Rand is supposed to be a phase.’”

Masters’ years in Palo Alto were in some ways comparable to Thiel’s. After coming to the United States from Germany as an infant, Thiel spent part of his childhood in apartheid-era South Africa, where his father oversaw engineers working on a uranium mine that was part of the regime’s secretive nuclear weapons program. The Thiels then settled in California, and Peter—a chess prodigy who was bullied by his classmates—went on to Stanford.

“He was not a hateful person,” says a college roommate. “He was a misinformed libertarian white 20-year-old. But they were a dime a dozen at Stanford.”

While there, he co-founded the conservative newspaper the Stanford Review, which was known for its “virulent” homophobia, as Max Chafkin reports in his Thiel biography, The Contrarian. One column argued that homophobia should be rebranded “miso-sodomy”—hatred of anal sex—to foreground “deviant sexual practices.” The author of the column, Nathan Linn, would go on to work for Thiel, who spent much of his life as a semi-closeted gay man. Several years after finishing Stanford Law, Thiel co-wrote a book, The Diversity Myth, that railed against progressivism at his alma mater, including its decision to provide benefits to LGBTQ employees’ domestic partners.

Like Thiel, Masters fought back against his peers with a mix of provocation, political purism, and disdain. In the one article he wrote for the Stanford Daily, Masters argued that voting is usually immoral because it leads to others being forced to pay taxes: “People who support what we euphemistically call ‘democracy’ or ‘representative government’ support stealing certain kinds of goods and redistributing them as they see fit.” He urged his fellow students not to participate in the 2006 midterms.

Masters moved off campus junior year but remained active in the Columbae community. For a co-op talent show that Masters was unable to attend during his senior year, he sent a video in which he rapped while wearing what was meant to resemble Native American war paint. “I’ve got the war paint on, as you can see,” he rhymed over a beat in the video, which was shared with Mother Jones. “Who said what about cultural insensitivity?”

After graduating, Masters kept emailing the Columbae listserv. The numerous messages shared with Mother Jones reveal a man largely unsympathetic to those who would lose out if his version of libertarianism prevailed. In a 2008 email, he fumed, “If you force someone to do something against their will, that is to say, if you initiate aggression against another human being (and subsequently attempt to justify it), not only are you a political enemy, but you’re a monster.” His frustrations extended across party lines. “When will someone start a group that’s pro-gun (pro-freedom) AND pro-choice (pro-freedom)?” he asked in one email. “I would join.” (Holding such a progressive view of abortion was not new; Masters had persuaded Wedel, who grew up in a conservative household, to support women’s right to have abortions nearly a decade before.)

At the time, Masters was working in sales at a cloud storage startup, while also pursuing interests that included “gold mining and other outdoor instances of throwback rugged individualism,” according to an archived version of his LinkedIn. Masters quickly dropped sales for Duke Law—a rare setback, by his high standards—then transferred back to Stanford in 2010. Masters remembers his best friend, Wedel, who was a year ahead of him at Stanford Law, suggesting they take a seminar called “Sovereignty, Technology, and Globalization.” Masters knew little about his new teacher other than that he was the tech giant who’d helped start PayPal.

Deena So’Oteh

Deena So’Oteh

Compared with the young libertarian and self-identified “aspiring rationalist” about to attend his lecture series, Thiel was already more amenable to using the state’s power to further his own interests. After co-founding PayPal and becoming Facebook’s first major outside investor, in 2004 Thiel started the surveillance company Palantir with Joe Lonsdale, whose future wife was also in the co-op with Masters. Thiel and Lonsdale set out to win federal contracts to help defense and immigration agencies mine massive government databases in the name of protecting national security. Thiel later wrote an essay suggesting that he saw a strongman leader as the way to survive a post-9/11 world.

It was in another essay, in 2009, “The Education of a Libertarian,” that Thiel declared he no longer believed that democracy and freedom were compatible. “Since 1920,” he argued, “the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women—two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians—have rendered the notion of ‘capitalist democracy’ into an oxymoron.” (Thiel, known for playing things close to the vest, would later say about that essay, “Writing is always such a dangerous thing.”) Thiel stressed that he still considered himself a libertarian because he opposed “confiscatory taxes, totalitarian collectives, and the ideology of the inevitability of the death of every individual.”

In a 2009 essay titled “The Education of a Libertarian,” Thiel declared he no longer believed that democracy and freedom were compatible.

Thiel’s views reflected the influence of a jumble of thinkers well outside the American mainstream, including German reactionaries like Oswald Spengler, who spent the Weimar era undermining the democracy that Adolf Hitler eventually destroyed. A dictatorship that championed industry, they believed, was essential to eliminating Weimar decadence. This combination—antidemocratic reaction on the one hand, an embrace of technology on the other—is key to Thiel’s thinking.

But unlike these German conservative revolutionaries, Thiel does not fetishize nationalism, even though he clearly understands its electoral potency. He has called The Sovereign Individual—written by the self-styled investment guru James Dale Davidson and the late British journalist William Rees-Mogg—the most influential book he’s ever read. Its main argument is that a new cosmopolitan elite will destroy countries’ ability to redistribute money by fleeing to whichever tiny jurisdictions offer them the best investment terms. (It helps explain why Thiel would later go to great lengths to acquire New Zealand citizenship.) These Sovereign Individuals will get to “interact on terms that echo the relation among the gods in Greek myth.” The “losers,” meanwhile, will be stuck in crumbling nations until they realize they “suffer for being saddled with mass democracy” and embrace privatized government. Along with this Sovereign Individualism, Thiel is a Christian who believes that heaven could potentially be realized on Earth through breakthroughs that allow humans to live forever.

Sitting in on Thiel’s “Sovereignty, Technology, and Globalization,” Masters quickly realized he was in the presence of a “next-level genius,” he said. For him, Thiel’s takes on subjects ranging from China to Leo Strauss—the political philosopher who argued that great thinkers embed secret meanings in their texts to avoid the sometimes fatal consequences of heterodoxy—became “holy shit” moments. While other students tried to impress Thiel after class, Masters waited until halfway through the seminar before emailing questions he’d find compelling. Thiel responded by suggesting they have dinner and quickly became an informal mentor to Masters, who was soon interning at Founders Fund, a VC firm that Thiel co-founded.

The next school year, Thiel let Masters know he’d be teaching an undergrad computer science course. Masters started attending and posting essays built off his class notes on Tumblr. The posts, which detailed Thiel’s ideas on how to run a successful startup, went viral within days and resulted in Masters writing a guest blog for Forbes on the 10 lessons he’d drawn from Thiel’s class. In the New York Times, columnist David Brooks praised the posts as “outstanding notes.”

Sitting in on Thiel’s “Sovereignty, Technology, and Globalization,” Masters quickly realized he was in the presence of a “next-level genius,” he said.

It was quite the leap for someone who a year earlier had been blogging about the challenge of maintaining “clean, paleo eating” as a summer law associate. On his Tumblr, Masters had adopted a new tagline so Thielian that it is still sometimes misattributed to the billionaire: “Your mind is software. Program it. Your body is a shell. Change it. Death is a disease. Cure it. Extinction is approaching. Fight it.” The actual source, Masters has explained, is a video game in which bioengineered humans in a postapocalyptic universe try to save transhumanity from extinction by joining a “secretive conspiracy.”

The most revealing of Thiel’s 19 lectures, though, was Masters’ favorite, “Founder as Victim, Founder as God.” Thiel told students that ancient societies resolved internal tensions by scapegoating founderlike figures who were often worshipped before being sacrificed, a circumstance that startup leaders also risked. Monarchy, Thiel speculated, might have arisen when scapegoats figured out how to become kings and avoid the sacrificial altar. “Wearing the crown is obviously an attractive thing,” Thiel said. “The question is whether you can decouple it with getting executed.” He concluded with a plea on behalf of the would-be techno-kings willing to break the rules. “Maybe they are, in some key way, the most important,” Thiel said. “Maybe we should let them off the hook.”

Blake Masters listens to Peter Thiel speaking at a book party hosted by Arianna Huffington for Thiel and Masters’ book, Zero to One.

J Grassi/Patrick McMullan/Sipa USA/AP

By the time Trump announced he was running for president in 2015, Masters had lost faith in Republicans’ ability to win elections. He found it hard to believe that Mitt Romney, a successful businessman, had been defeated by Barack Obama, whose first term he considered a disaster. Masters was convinced that Romney had played too nice. “If Republicans just aren’t gonna be serious about winning,” he later explained in a podcast interview, “maybe it’s just a controlled opposition and we’re just gonna have a managed decline politically.” Masters was in a dark place when it came to the future of American politics, and America itself. “I basically thought it was all over,” he said.

Having soured on government, he turned to the private sector, pouring his energy into his legal research startup and working with Thiel to turn the Stanford lectures into a book. Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future became an instant bestseller in 2014; it also reflected their pessimism about politics. The title referred to the “zero to one” moments when someone did something that had never been done before. For Thiel and Masters, such breakthroughs were key to humanity’s survival, and they concluded with an existential warning: “Without new technology to relieve competitive pressures, stagnation is likely to erupt into conflict. In case of conflict on a global scale, stagnation collapses into extinction.”

Initially, Thiel backed Carly Fiorina, the former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, in the 2016 Republican primary. After Fiorina dropped out, Thiel signed up as a Trump delegate, spoke at the Republican National Convention, and donated $1.25 million to super-PACs still supporting Trump in the wake of the Access Hollywood tape. Thiel’s status as progressives’ Silicon Valley villain was further cemented by the news that he’d been secretly bankrolling a lawsuit by Terry Bollea, better known as the wrestler Hulk Hogan, that led to Gawker Media declaring bankruptcy in 2016. Funding the case was Thiel’s revenge for articles the company had written about him, including one titled “Peter Thiel is totally gay, people.” (While Thiel had come out to friends, it had not been reported that he was gay.)

Thiel secretly bankrolled the lawsuit by Terry Bollea, better known as the wrestler Hulk Hogan, that led to Gawker Media declaring bankruptcy in 2016.

For Masters, Trump’s rise became a zero-to-one moment that revealed new things were possible in politics. Trump could break with Republican orthodoxy, attack John McCain for being captured in Vietnam, and brag that he could shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue—all while winning primary after primary. He was the scapegoat figuring out how to become king.

After the election, Thiel, Masters, and other members of the billionaire’s entourage headed to Trump Tower to try to push the new administration in an extreme direction. Thiel’s choice to be Trump’s science adviser, William Happer, was a climate change denier who believed the world was suffering from a “carbon dioxide famine,” Chafkin reported in his biography of Thiel. Happer, like most of Thiel’s picks, didn’t get the job. Masters believed Trump’s agenda was being hijacked by establishment Republicans and hangers-on. He started thinking about a world in which he was more than a supplicant.

In 2018, Masters and his family settled back in Tucson around the same time Thiel promoted him to chief of staff. Thiel was known for recruiting young, ambitious Stanford grads; Masters had emerged at the top of the heap. A year later, he considered, then decided against, launching a primary challenge against Sen. Martha McSally. When McSally lost a special election to Mark Kelly in November 2020, Masters became convinced that he was the only person who could unseat the freshman Democrat. Less than six months later, Thiel put $10 million into a super-PAC backing Masters.

Masters arrives for his town hall event at Miss Kitty’s Steak House in Williams, Arizona.

Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/AP

Masters launched his campaign with a sepia-toned video he said was inspired by the work of director Terrence Malick. “I grew up here,” Masters intoned before staring off into the distance. He pledged to finish the wall, create an economy where families could thrive on one income, and end foreign interventionism. It was all delivered in an unusually deep voice. “Just not the guy I knew,” his prep school friend Noah Gustafson texted Wedel. “He even sounds different!”

Masters’ main primary opponents were Jim Lamon, a wealthy solar energy entrepreneur, and Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, whose name recognition positioned him as the early frontrunner. But Brnovich had one big weakness that Masters was prepared to exploit: He’d admitted that Trump had lost to Biden. Like Trump, Masters weaponized Twitter to criticize Brnovich for not doing enough to investigate election fraud conspiracies. He also tweeted multiple times that “not everything has to be gay,” and, in a departure from his early pro-choice stance, began a campaign video about abortion by declaring, “There’s a genocide happening in America.” (Masters has come out in favor of a federal personhood law.) Gustafson was struck by the total lack of empathy he saw from his old friend. “It makes me ache when I see what he writes and says,” he says. “It puts me in a state of depression.”

Wedel, who’d taken a hiatus from social media, received texts from his brothers with screenshots of Masters’ tweets. On November 4, he saw a Masters tweet calling vaccine mandates evil. “Shame on you,” Wedel replied, after re-downloading Twitter. “I’m so utterly disappointed in what you’ve done with yourself. People will get sick, and die, because of your reckless rhetoric. As someone who loves and used to respect you: What happened to you?”

“People will get sick, and die, because of your reckless rhetoric,” Wedel tweeted. “As someone who loves and used to respect you: What happened to you?”

Only Masters and a few dozen people close to Wedel could see the message from his private account. Instead of talking to Wedel, or just ignoring it, Masters responded by screenshotting the reply and sharing it with tens of thousands of followers. “Collin was a best friend growing up. He told me about the famous class where I met Peter Thiel, and he was best man at my wedding,” Masters wrote. “The most deadly virus we face is progressivism, it rots both brains and nations. I wish Collin well—but freedom is worth losing friends over.” Wedel received harassing calls at work and home, and had to call the police after threatening materials were placed in his mailbox.

Blake Masters and Collin Wedel in their high school yearbook

Wedel stresses that he will always love Masters as a brother, but the two have not spoken since. “I don’t know what’s worse,” he adds, “if he actually is aware that he’s selling snake oil to people, or if he truly believes” what he’s saying.

Masters, who says he stopped considering himself a libertarian years ago, is no longer the open-border purist of his youth. Like Lee Kuan Yew, the late Singaporean dictator whom Masters has called one of his two favorite historical figures (alongside George Washington), he has come around to the appeal of a government that takes sides, promotes conservative values, and has the capacity to build new things. Masters also isn’t the middle-class champion he sometimes sells himself as. He says he wants families to be able to thrive on one income, but hasn’t put forward a coherent plan for making that happen.

Intentionally or not, Masters is following a strategy championed decades ago by one of his old favorites, Murray Rothbard, who died in 1995. A libertarian economist and philosopher, Rothbard appreciated the potential of yoking libertarianism to right-wing populism, as the writer John Ganz has explained. In a 1992 essay that began by expressing sympathy for David Duke, the former Ku Klux Klan leader who had recently lost his bid for governor in Louisiana, Rothbard laid out an eight-plank platform for advancing libertarianism: cutting taxes, slashing welfare, abolishing racial privileges, crushing criminals (“I mean, of course, not ‘white collar criminals’”), getting rid of “bums,” eliminating the Federal Reserve, being “America First,” and defending family values.

Rothbard called this “paleolibertarianism,” and Masters has brought it up to date. The Masters incarnation favors the Trump tax cuts that overwhelmingly benefited the wealthiest Americans; sees the end of entitlement programs as an inevitability; labels critical race theory “anti-white racism”; shot a campaign video in which he walks through a San Francisco homeless encampment; courts anti-Fed crypto bros; describes the situation at the US-Mexico border as an “invasion”; and says marriage is between “a man and a woman” after spending most of the past decade working for a man who is now married to another man.

Extremists have taken notice and approved. VDare, a white nationalist site named after the first English child born in the Americas, has called Masters “the America First contender” in Arizona. Andrew Anglin, the founder of the neo-Nazi Daily Stormer website, is another fan, although Masters has rejected his support. “Masters is better than Vance,” Anglin explained. “Masters is woke on Uncle Ted”—a reference to the Unabomber—“he’s married to a white women [sic]…and now he’s dropping the red pills we all wanted to hear.” (Vance’s wife is Indian American.)

VDare, a white-nationalist-friendly site named after the first English child born in the Americas, has called Masters “the America First contender” in Arizona.

Anglin is right that Masters’ campaign is filled with nods to the red-pilled members of the online right. At one campaign stop, the crowd cheered after Masters talked up a plan that a “friend” of his has to “RAGE,” or Retire All Government Employees. What he didn’t say was that friend is Curtis Yarvin, the absolute-monarchist blogger who believes Americans need to get over their “dictator-phobia.” Yarvin, who has known Thiel for years, recently gave Masters his first campaign contribution on record: the legal maximum of $5,800. (Two of his other biggest backers are the Winklevoss twins, the Harvard rowers turned crypto moguls who claim Mark Zuckerberg stole the idea for Facebook from them.)

Masters has been reading Yarvin’s work for at least a decade. In 2012, his former college roommate Christina asked for a suggestion for a book club focused on sustainability and overconsumption. Masters recommended they read a series of articles in which Yarvin made the case for why the United States should become a monarchy headed by a CEO. He thought focusing on overconsumption was a distraction from deeper issues like the “sustainability of sovereignty” and government spending. “The pushback to this is that my views are very idiosyncratic and very few people agree with me,” Masters wrote in the email. “To the extent there’s validation in numbers, I don’t have any.”