Archive for category: Uncategorized

The imminent overturn of Roe v. Wade, coming on top of decades of what many activists consider to be an overly cautious abortion rights movement, is having ripple effects in reproductive rights organizations and clinics, according to Emily Likins-Ehlers, who’s with the group ReproJobs, a worker empowerment center recently highlighted by The Intercept. “People are just trying to grab control where they can,” Likins-Ehlers said. “Making sure that they have a severance when they lose their job in two weeks or whatever has been on the forefront of most workers’ minds that I’ve spoken with. They just want to pay their bills after Roe falls.”

ReproJobs is a nonprofit run by two anonymous organizers who work in the reproductive rights field, as well as Likins-Ehlers. The group has widely followed and influential Instagram and Twitter accounts focused on workplace organizing and discontent inside reproductive rights workplaces. Likins-Ehlers offered to do an interview about the group and its role, which was mentioned in our story on the implosion of the progressive nonprofit world in Washington, D.C., adding that the two co-founders are continuing to remain anonymous.

“I don’t envy anyone who has to manage an organization right now, particularly, but I think they would find that they could actually find more resources if they were willing to ally themselves with the union, by accepting the union into their space,” Likins-Ehlers said, though they agreed with the executive directors cited in The Intercept article that a generational divide and a culture that encourages callouts have made organizations more difficult to manage. Turmoil in progressive organizations generally, and reproductive rights groups specifically, isn’t explained by the presence of a union drive. Some organizations going through upheaval have been unionized for decades, such as NARAL Pro-Choice America or the Sierra Club, while others, like the Guttmacher Institute and Groundswell Fund, are seeing fresh union drives.

There’s a fear, Likins-Ehlers said, that many organizations will soon shut down and blame the union. “That’s what a lot of these reproductive justice orgs will do,” Likins-Ehlers said, referring to a previous organization they had worked with that did just that. “They’ll say, ‘Roe fell, and this became too hard. And I’m too scared of getting arrested. And I guess the union was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and now we have to close.’”

At the same time, Likins-Ehlers said, things have not been going well under the current and former executive directors. “If the managers feel like the conditions are becoming unworkable, that means that the workers are doing a good job disrupting the system. And I think that most of these workers right now know that it’s toast. We’re fucked. Roe is going to fall any day now. And we are going to have to set up bail funds.”

Likins-Ehlers said they work as a part-time contractor for ReproJobs. The two anonymous founders go by the pseudonyms Hermione and Luna. The budget for the operation, ReproJobs said, is around $275,000 this year, and the major funding began around 2019. “If they feel like they can’t rise to this challenge,” Likins-Ehlers said of the managers at nonprofits, “they can get out of the way and let somebody else rise to this challenge. Because there is a generational gap, and more people are unionizing now than ever before.”

“If the managers feel like the conditions are becoming unworkable, that means that the workers are doing a good job disrupting the system.”

Likins-Ehlers said that they had recently been in a webinar with one of their movement heroes, Loretta Ross, an author, activist, and reproductive justice pioneer. Ross, who was featured in The Intercept’s article, has been publicly advocating against callout culture in progressive organizations for several years.

“I really respect Loretta Ross and everything she has to say, and she sort of gave me the business during a webinar a few weeks ago, where she told me that when she was a young organizer, you were lucky to have a sleeping bag on the floor of a church when you went to a protest. Things were different. There weren’t jobs in the movement 50 years ago; this is a new industry that is just forming,” they said.

“Loretta has a book coming out that sort of disrupts callout culture in a really powerful way, and so I think that there’s been a lot of calling out that’s happened in the organizing efforts — specific executive directors have been targeted and have been ousted from their positions of power — and when I speak to workers, I don’t encourage that kind of calling out because I don’t feel like it builds collective power. I feel like it will simply give you a new figurehead to the same dynamic. So when we create a union, we’re simply trying to disrupt the power dynamic in and of itself and say, ‘This isn’t about you, as a leader, or you as a person necessarily. This is about a system, a structure.’”

Likins-Ehlers said that there are indeed examples of employees who lean too heavily into callouts of management over issues that should be handled differently, but that it’s important to separate those instances from the worthy goal of improving workplaces generally. “Loretta Ross said to me that she had an employee that called her out because the employee’s cat died, and she wanted time off to mourn her cat, and Loretta was unwilling to give her time off to mourn her cat or something like this. And that was Loretta’s example of the kinds of conflicts that are happening with the unions, and I had to kind of shrug because I was like, yeah, if a worker came to me with that story, I would tell them to deal with it personally. That’s not what we’re talking about. We are talking about living wages, we’re talking about parental leave. We are talking about the right to have a real job and not a temporary job that can be pulled out from underneath you at any moment. We’re talking about the right to work-life balance.”

Likins-Ehlers added that there were also cultural issues at work, recalling a previous boss of theirs who behaved transphobically. “Our executive director would deadname people,” they said, adding:

So just because you are the director of an abortion clinic doesn’t mean that you are respectful of transgender people. So I’m not saying that Loretta is wrong or that any of these leaders are wrong. They’re right also. But why don’t they just join us? They really aren’t the boss, they are employed by a board of directors. All of these executive directors are just an employee, just like us. Just like the rest of the workers who are trying to unionize, they have a boss, but their boss is a volunteer board of directors instead of an individual. So it’s harder to target. But that is really who runs these nonprofits. It’s not the EDs. The boards are the ones, and these are often people who are wealthy or work in other industries or are high-powered lawyers — like Planned Parenthood has these, like, super high-powered, amazing lawyers who could be spending their time strengthening the movement but instead spend their time fighting the unions, when really the only thing that anybody wants is just a formal contract.

Most of these employees, when they come to me, they’re like: “I don’t want my clinic to shut down. I don’t want my organization to be burdened. I’m not looking for a raise.” They literally just want a formal employment contract. Because we all feel so insecure in this job economy, like you said. So I don’t know. There’s just, I think, cognitive dissonance because, like, I’m holding Loretta Ross’s book, right here, “An Introduction To Reproductive Justice.” And she says, specifically, quote, “Reproductive justice explains that indeed, poverty creates poor conditions for mothering, because it shortens lifespans and increases rates of infant and child mortality and lower birth weights.” So if we’re talking about poverty wages, that’s what a lot of these reproductive justice workers are making in their cities: poverty wages. I made way more money as a busser at a pizza place than I made at the clinic. So for them to question our loyalty to the movement feels really rude.

The cautious politics of many of the leading abortion rights groups, Likins-Ehlers said, also helped bring about the catastrophe the movement is now facing. “When I started in the abortion movement back in 2012, they told me that I wasn’t allowed to use the word abortion as I advocated, that we could only say ‘a woman’s right to choose’ — that saying the word abortion was too radical and too leftist. And I got put on a list, like, ‘Emily’s not allowed to talk to people because she’s too radical about what she says.’ So I’ve always been a disrupter, everywhere I’ve gone. You can ask anyone who’s worked with me, I’m a pain in the fucking ass,” they said. “I felt this moment coming for so many years. And I feel like the movement has — we have been failed.”

The post ReproJobs’ Emily Likins-Ehlers: Overly Cautious Organizations and Imminent Roe Overturn Are Driving Staff Dissent appeared first on The Intercept.

Elizabeth Woodruff drained her retirement account and took on three jobs after she and her husband were sued for nearly $10,000 by the New York hospital where his infected leg was amputated.

Ariane Buck, a young father in Arizona who sells health insurance, couldn’t make an appointment with his doctor for a dangerous intestinal infection because the office said he had outstanding bills.

Allyson Ward and her husband loaded up credit cards, borrowed from relatives, and delayed repaying student loans after the premature birth of their twins left them with $80,000 in debt. Ward, a nurse practitioner, took on extra nursing shifts, working days and nights.

“I wanted to be a mom,” she said. “But we had to have the money.”

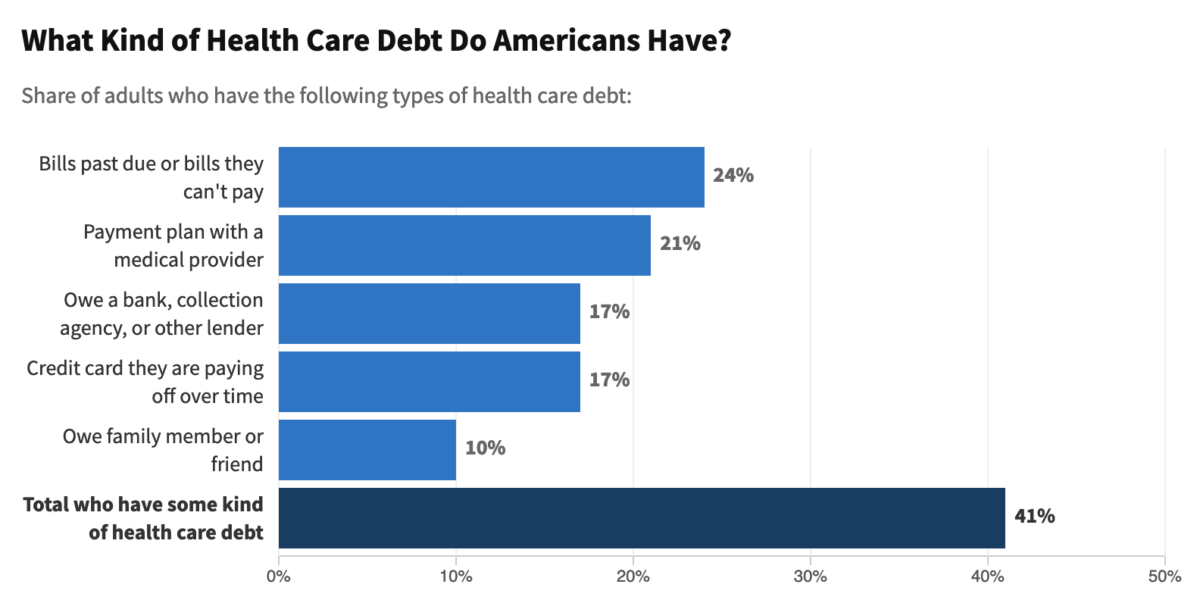

The three are among more than 100 million people in America ― including 41% of adults ― beset by a health care system that is systematically pushing patients into debt on a mass scale, an investigation by KHN and NPR shows.

The investigation reveals a problem that, despite new attention from the White House and Congress, is far more pervasive than previously reported. That is because much of the debt that patients accrue is hidden as credit card balances, loans from family, or payment plans to hospitals and other medical providers.

To calculate the true extent and burden of this debt, the KHN-NPR investigation draws on a nationwide poll conducted by KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) for this project. The poll was designed to capture not just bills patients couldn’t afford, but other borrowing used to pay for health care as well. New analyses of credit bureau, hospital billing, and credit card data by the Urban Institute and other research partners also inform the project. And KHN and NPR reporters conducted hundreds of interviews with patients, physicians, health industry leaders, consumer advocates, and researchers.

The picture is bleak.

In the past five years, more than half of U.S. adults report they’ve gone into debt because of medical or dental bills, the KFF poll found.

A quarter of adults with health care debt owe more than $5,000. And about 1 in 5 with any amount of debt said they don’t expect to ever pay it off.

“Debt is no longer just a bug in our system. It is one of the main products,” said Dr. Rishi Manchanda, who has worked with low-income patients in California for more than a decade and served on the board of the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt. “We have a health care system almost perfectly designed to create debt.”

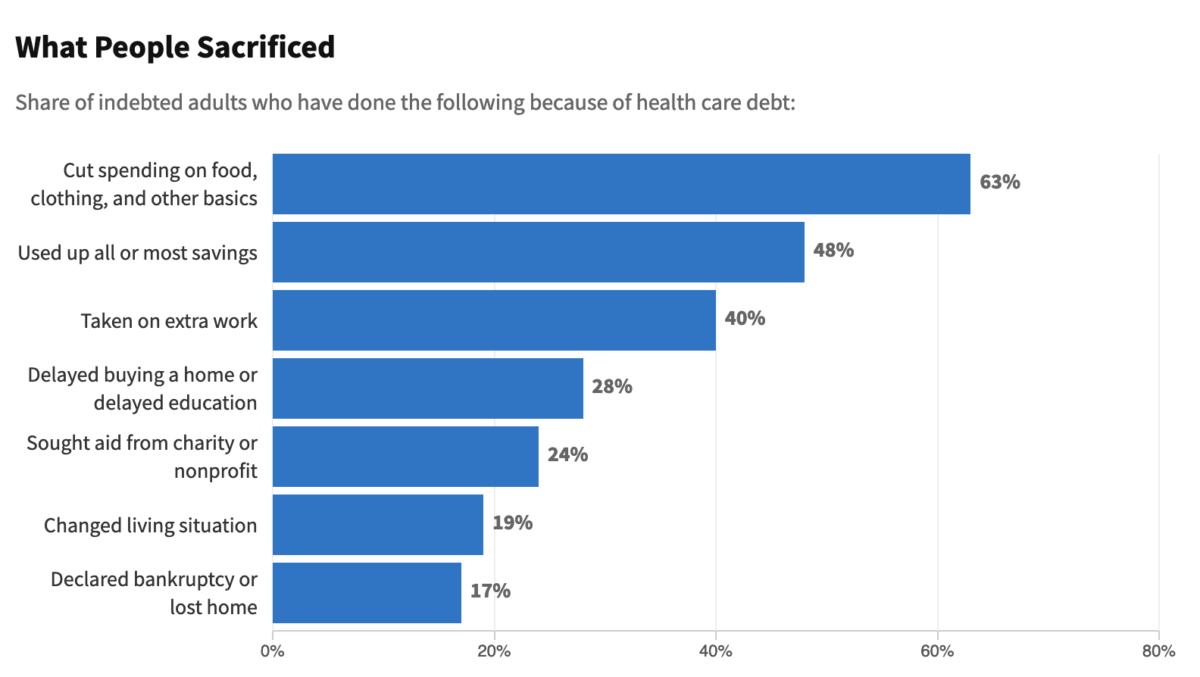

The burden is forcing families to cut spending on food and other essentials. Millions are being driven from their homes or into bankruptcy, the poll found.

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

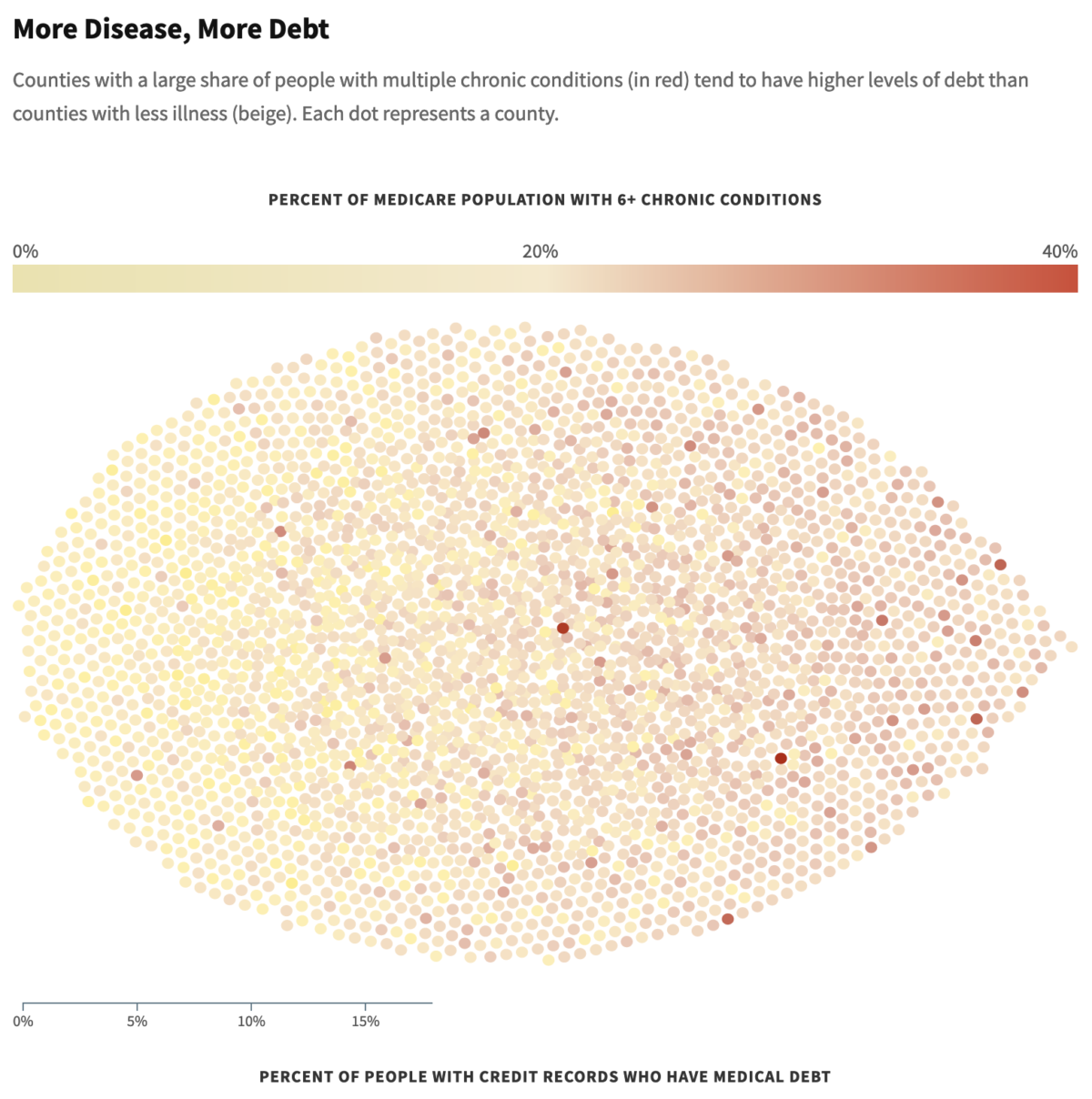

Medical debt is piling additional hardships on people with cancer and other chronic illnesses. Debt levels in U.S. counties with the highest rates of disease can be three or four times what they are in the healthiest counties, according to an Urban Institute analysis.

The debt is also deepening racial disparities.

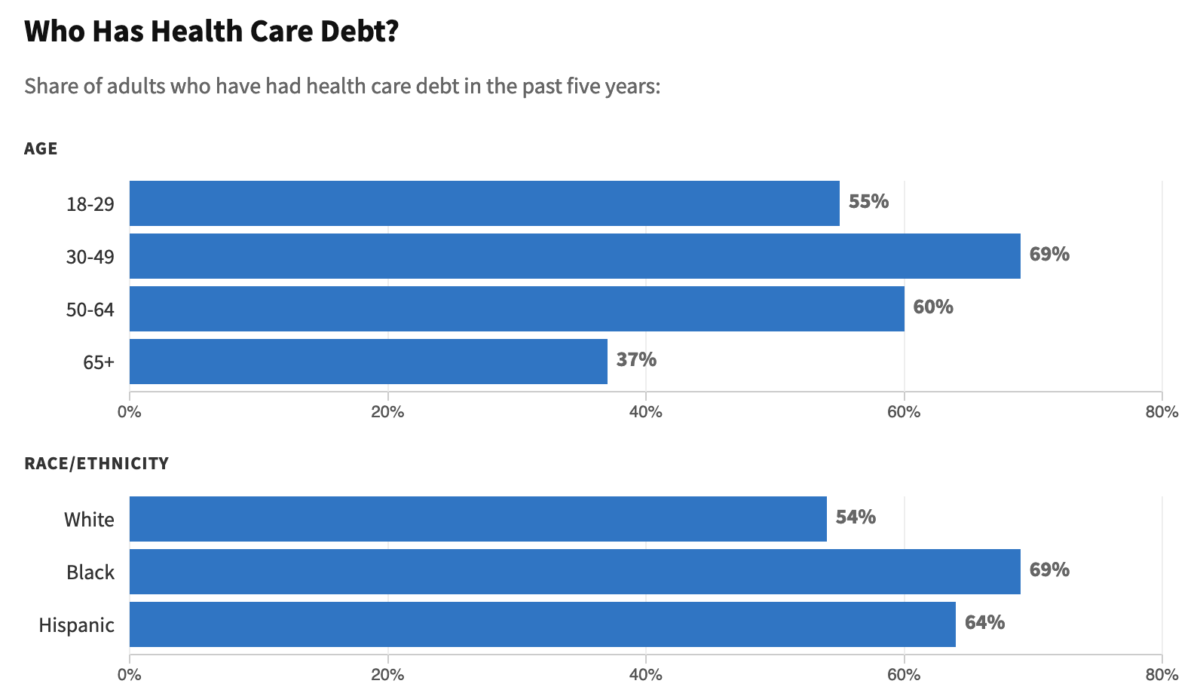

And it is preventing Americans from saving for retirement, investing in their children’s educations, or laying the traditional building blocks for a secure future, such as borrowing for college or buying a home. Debt from health care is nearly twice as common for adults under 30 as for those 65 and older, the KFF poll found.

Perhaps most perversely, medical debt is blocking patients from care.

About 1 in 7 people with debt said they’ve been denied access to a hospital, doctor, or other provider because of unpaid bills, according to the poll. An even greater share ― about two-thirds ― have put off care they or a family member need because of cost.

“It’s barbaric,” said Dr. Miriam Atkins, a Georgia oncologist who, like many physicians, said she’s had patients give up treatment for fear of debt.

Patient debt is piling up despite the landmark 2010 Affordable Care Act.

The law expanded insurance coverage to tens of millions of Americans. Yet it also ushered in years of robust profits for the medical industry, which has steadily raised prices over the past decade.

Hospitals recorded their most profitable year on record in 2019, notching an aggregate profit margin of 7.6%, according to the federal Medicare Payment Advisory Committee. Many hospitals thrived even through the pandemic.

But for many Americans, the law failed to live up to its promise of more affordable care. Instead, they’ve faced thousands of dollars in bills as health insurers shifted costs onto patients through higher deductibles.

Now, a highly lucrative industry is capitalizing on patients’ inability to pay. Hospitals and other medical providers are pushing millions into credit cards and other loans. These stick patients with high interest rates while generating profits for the lenders that top 29%, according to research firm IBISWorld.

Patient debt is also sustaining a shadowy collections business fed by hospitals ― including public university systems and nonprofits granted tax breaks to serve their communities ― that sell debt in private deals to collections companies that, in turn, pursue patients.

“People are getting harassed at all hours of the day. Many come to us with no idea where the debt came from,” said Eric Zell, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland. “It seems to be an epidemic.”

In Debt to Hospitals, Credit Cards, and Relatives

America’s debt crisis is driven by a simple reality: Half of U.S. adults don’t have the cash to cover an unexpected $500 health care bill, according to the KFF poll.

As a result, many simply don’t pay. The flood of unpaid bills has made medical debt the most common form of debt on consumer credit records.

As of last year, 58% of debts recorded in collections were for a medical bill, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. That’s nearly four times as many debts attributable to telecom bills, the next most common form of debt on credit records.

But the medical debt on credit reports represents only a fraction of the money that Americans owe for health care, the KHN-NPR investigation shows.

- About 50 million adults ― roughly 1 in 5 ― are paying off bills for their own care or a family member’s through an installment plan with a hospital or other provider, the KFF poll found. Such debt arrangements don’t appear on credit reports unless a patient stops paying.

- One in 10 owe money to a friend or family member who covered their medical or dental bills, another form of borrowing not customarily measured.

- Still more debt ends up on credit cards, as patients charge their bills and run up balances, piling high interest rates on top of what they owe for care. About 1 in 6 adults are paying off a medical or dental bill they put on a card.

How much medical debt Americans have in total is hard to know because so much isn’t recorded. But an earlier KFF analysis of federal data estimated that collective medical debt totaled at least $195 billion in 2019, larger than the economy of Greece.

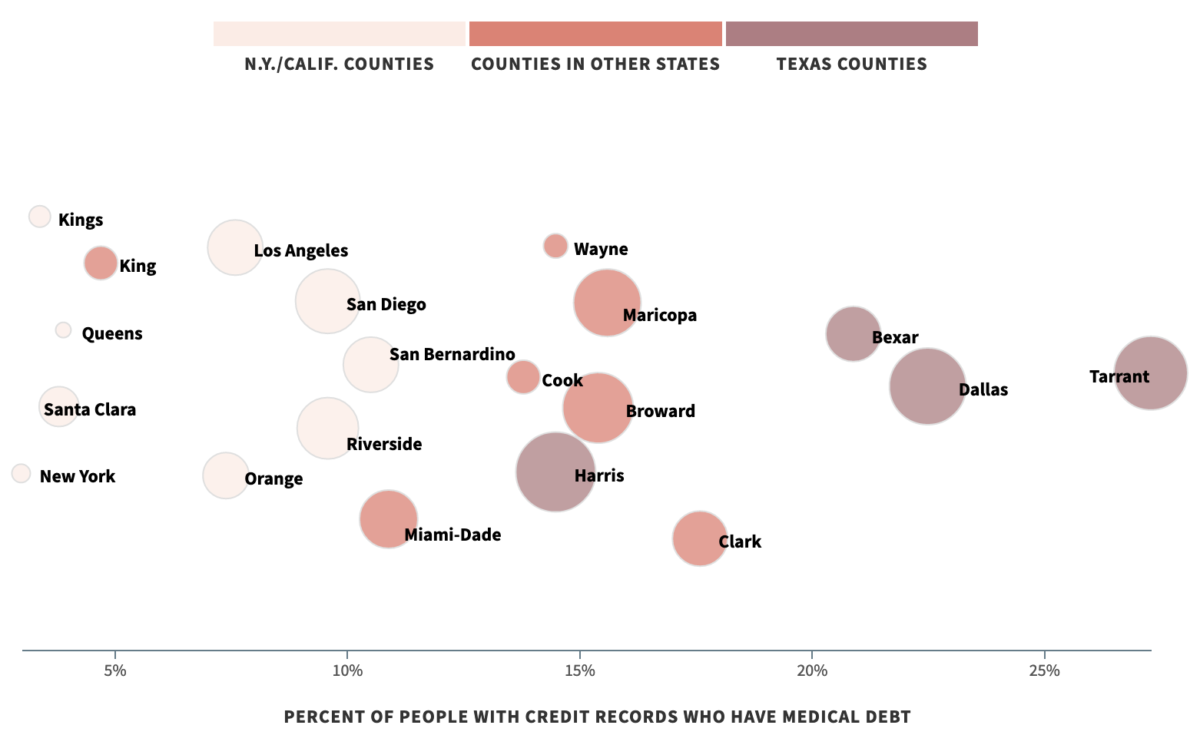

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe for KHN and Alyson Hurt / NPR

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe for KHN and Alyson Hurt / NPR

The credit card balances, which also aren’t recorded as medical debt, can be substantial, according to an analysis of credit card records by the JPMorgan Chase Institute. The financial research group found that the typical cardholder’s monthly balance jumped 34% after a major medical expense.

Monthly balances then declined as people paid down their bills. But for a year, they remained about 10% above where they had been before the medical expense. Balances for a comparable group of cardholders without a major medical expense stayed relatively flat.

It’s unclear how much of the higher balances ended up as debt, as the institute’s data doesn’t distinguish between cardholders who pay off their balance every month from those who don’t. But about half of cardholders nationwide carry a balance on their cards, which usually adds interest and fees.

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

Debts Large and Small

For many Americans, debt from medical or dental care may be relatively low. About a third owe less than $1,000, the KFF poll found.

Even small debts can take a toll.

Edy Adams, a 31-year-old medical student in Texas, was pursued by debt collectors for years for a medical exam she received after she was sexually assaulted.

Adams had recently graduated from college and was living in Chicago.

Police never found the perpetrator. But two years after the attack, Adams started getting calls from collectors saying she owed $130.68.

Illinois law prohibits billing victims for such tests. But no matter how many times Adams explained the error, the calls kept coming, each forcing her, she said, to relive the worst day of her life.

Sometimes when the collectors called, Adams would break down in tears on the phone. “I was frantic,” she recalled. “I was being haunted by this zombie bill. I couldn’t make it stop.”

Health care debt can also be catastrophic.

Sherrie Foy, 63, and her husband, Michael, saw their carefully planned retirement upended when Foy’s colon had to be removed.

After Michael retired from Consolidated Edison in New York, the couple moved to rural southwestern Virginia. Sherrie had the space to care for rescued horses.

The couple had diligently saved. And they had retiree health insurance through Con Edison. But Sherrie’s surgery led to numerous complications, months in the hospital, and medical bills that passed the $1 million cap on the couple’s health plan.

When Foy couldn’t pay more than $775,000 she owed the University of Virginia Health System, the medical center sued, a once common practice that the university said it has reined in. The couple declared bankruptcy.

The Foys cashed in a life insurance policy to pay a bankruptcy lawyer and liquidated savings accounts the couple had set up for their grandchildren.

“They took everything we had,” Foy said. “Now we have nothing.”

About 1 in 8 medically indebted Americans owe $10,000 or more, according to the KFF poll.

Although most expect to repay their debt, 23% said it will take at least three years; 18% said they don’t expect to ever pay it off.

Medical Debt’s Wide Reach

Debt has long lurked in the shadows of American health care.

In the 19th century, male patients at New York’s Bellevue Hospital had to ferry passengers on the East River and new mothers had to scrub floors to pay their debts, according to a history of American hospitals by Charles Rosenberg.

The arrangements were mostly informal, however. More often, physicians simply wrote off bills patients couldn’t afford, historian Jonathan Engel said. “There was no notion of being in medical arrears.”

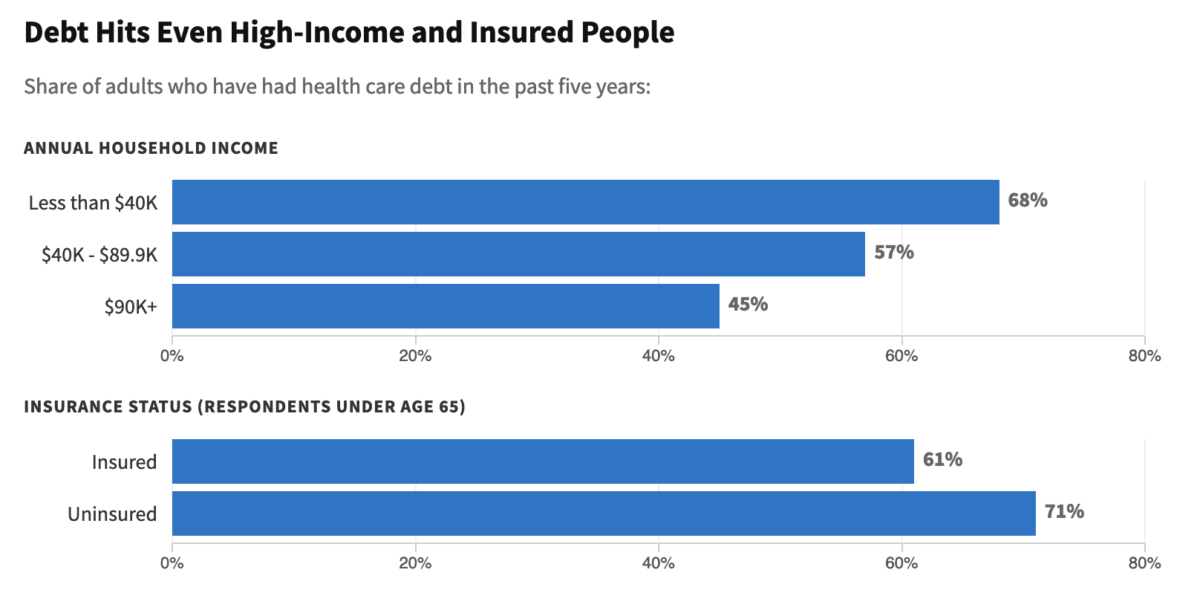

Today, debt from medical and dental bills touches nearly every corner of American society, burdening even those with insurance coverage through work or government programs such as Medicare.

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

Nearly half of Americans in households making more than $90,000 a year have incurred health care debt in the past five years, the KFF poll found.

Women are more likely than men to be in debt. And parents more commonly have health care debt than people without children.

But the crisis has landed hardest on the poorest and uninsured.

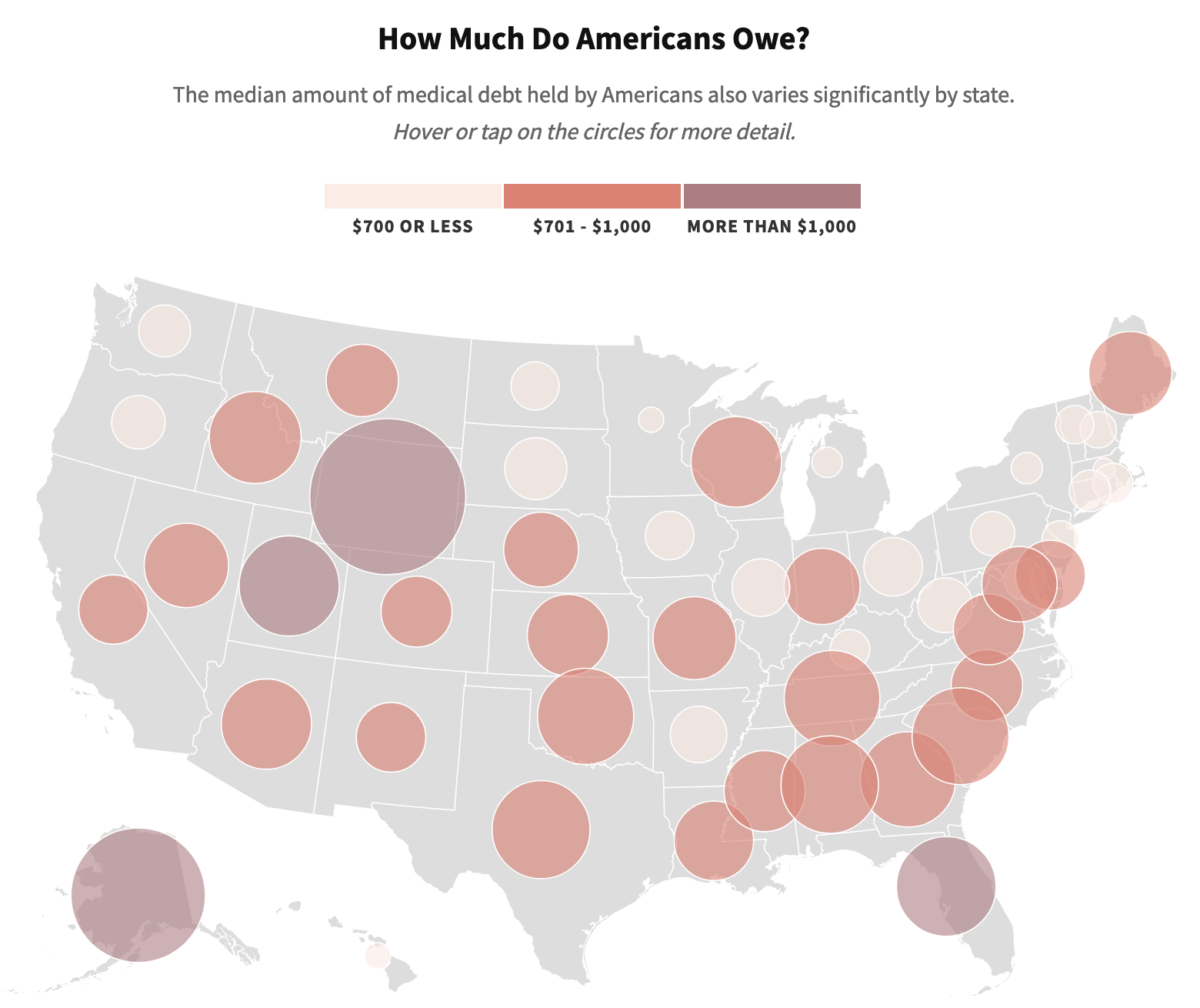

Debt is most widespread in the South, an analysis of credit records by the Urban Institute shows. Insurance protections there are weaker, many of the states haven’t expanded Medicaid, and chronic illness is more widespread.

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

Nationwide, according to the poll, Black adults are 50% more likely and Hispanic adults 35% more likely than whites to owe money for care. (Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races.)

In some places, such as the nation’s capital, disparities are even larger, Urban Institute data shows: Medical debt in Washington, D.C.’s predominantly minority neighborhoods is nearly four times as common as in white neighborhoods.

In minority communities already struggling with fewer educational and economic opportunities, the debt can be crippling, said Joseph Leitmann-Santa Cruz, chief executive of Capital Area Asset Builders, a nonprofit that provides financial counseling to low-income Washington residents. “It’s like having another arm tied behind their backs,” he said.

Medical debt can also keep young people from building savings, finishing their education, or getting a job. One analysis of credit data found that debt from health care peaks for typical Americans in their late 20s and early 30s, then declines as they get older.

Cheyenne Dantona’s medical debt derailed her career before it began.

Dantona, 31, was diagnosed with blood cancer while in college. The cancer went into remission, but when Dantona changed health plans, she was hit with thousands of dollars of medical bills because one of her primary providers was out of network.

She enrolled in a medical credit card, only to get stuck paying even more in interest. Other bills went to collections, dragging down her credit score. Dantona still dreams of working with injured and orphaned wild animals, but she’s been forced to move back in with her mother outside Minneapolis.

“She’s been trapped,” said Dantona’s sister, Desiree. “Her life is on pause.”

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

Barriers to Care

Desiree Dantona said the debt has also made her sister hesitant to seek care to ensure her cancer remains in remission.

Medical providers say this is one of the most pernicious effects of America’s debt crisis, keeping the sick away from care and piling toxic stress on patients when they are most vulnerable.

The financial strain can slow patients’ recovery and even increase their chances of death, cancer researchers have found.

Yet the link between sickness and debt is a defining feature of American health care, according to the Urban Institute, which analyzed credit records and other demographic data on poverty, race, and health status.

U.S. counties with the highest share of residents with multiple chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease, also tend to have the most medical debt. That makes illness a stronger predictor of medical debt than either poverty or insurance.

In the 100 U.S. counties with the highest levels of chronic disease, nearly a quarter of adults have medical debt on their credit records, compared with fewer than 1 in 10 in the healthiest counties.

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data and the 2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

Tabulations of the August 2021 Urban Institute credit bureau data and the 2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data.Juweek Adolphe / Alyson Hurt for KHN and NPR

The problem is so pervasive that even many physicians and business leaders concede debt has become a black mark on American health care.

“There is no reason in this country that people should have medical debt that destroys them,” said George Halvorson, former chief executive of Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest integrated medical system and health plan. KP has a relatively generous financial assistance policy but does sometimes sue patients. (The health system is not affiliated with KHN.)

Halvorson cited the growth of high-deductible health insurance as a key driver of the debt crisis. “People are getting bankrupted when they get care,” he said, “even if they have insurance.”

Washington’s Role

The Affordable Care Act bolstered financial protections for millions of Americans, not only increasing health coverage but also setting insurance standards that were supposed to limit how much patients must pay out of their own pockets.

By some measures, the law worked, research shows. In California, there was an 11% decline in the monthly use of payday loans after the state expanded coverage through the law.

But the law’s caps on out-of-pocket costs have proven too high for most Americans. Federal regulations allow out-of-pocket maximums on individual plans up to $8,700.

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

KFF Health Care Debt Survey of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,674 with current or past debt from medical or dental bills, conducted Feb. 25 through March 20. The margin of sampling error for the overall sample is 3 percentage points.Daniel Wood / NPR and Noam N. Levey / KHN

Additionally, the law did not stop the growth of high-deductible plans, which have become standard over the past decade. That has forced many Americans to pay thousands of dollars out of their own pockets before their coverage kicks in.

Last year the average annual deductible for a single worker with job-based coverage topped $1,400, almost four times what it was in 2006, according to an annual employer survey by KFF. Family deductibles can top $10,000.

While health plans are requiring patients to pay more, hospitals, drugmakers, and other medical providers are raising prices.

From 2012 to 2016, prices for medical care surged 16%, almost four times the rate of overall inflation, a report by the nonprofit Health Care Cost Institute found.

For many Americans, the combination of high prices and high out-of-pocket costs almost inevitably means debt. The KFF poll found that 6 in 10 working-age adults with coverage have gone into debt getting care in the past five years, a rate only slightly lower than the uninsured.

Even Medicare coverage can leave patients on the hook for thousands of dollars in charges for drugs and treatment, studies show.

About a third of seniors have owed money for care, the poll found. And 37% of these said they or someone in their household have been forced to cut spending on food, clothing, or other essentials because of what they owe; 12% said they’ve taken on extra work.

The widespread burden of medical debt has sparked new interest from elected officials, regulators, and industry leaders.

In March, following warnings from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the major credit reporting companies said they would remove medical debts under $500 and those that had been repaid from consumer credit reports.

In April, the Biden administration announced a new CFPB crackdown on debt collectors and an initiative by the Department of Health and Human Services to gather more information on how hospitals provide financial aid.

The actions were applauded by patient advocates. However, the changes likely won’t address the root causes of this national crisis.

“The No. 1 reason, and the No. 2, 3, and 4 reasons, that people go into medical debt is they don’t have the money,” said Alan Cohen, a co-founder of insurer Centivo who has worked in health benefits for more than 30 years. “It’s not complicated.”

Buck, the father in Arizona who was denied care, has seen this firsthand while selling Medicare plans to seniors. “I’ve had old people crying on the phone with me,” he said. “It’s horrifying.”

Now 30, Buck faces his own struggles. He recovered from the intestinal infection, but after being forced to go to a hospital emergency room, he was hit with thousands of dollars in medical bills.

More piled on when Buck’s wife landed in an emergency room for ovarian cysts.

Today the Bucks, who have three children, estimate they owe more than $50,000, including medical bills they put on credit cards that they can’t pay off.

“We’ve all had to cut back on everything,” Buck said. The kids wear hand-me-downs. They scrimp on school supplies and rely on family for Christmas gifts. A dinner out for chili is an extravagance.

“It pains me when my kids ask to go somewhere, and I can’t,” Buck said. “I feel as if I’ve failed as a parent.”

The couple is preparing to file for bankruptcy.

About This Project

“Diagnosis: Debt” is a reporting partnership between KHN and NPR exploring the scale, impact, and causes of medical debt in America.

The series draws on the “KFF Health Care Debt Survey,” a poll designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at KFF in collaboration with KHN journalists and editors. The survey was conducted Feb. 25 through March 20, 2022, online and via telephone, in English and Spanish, among a nationally representative sample of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,292 adults with current health care debt and 382 adults who had health care debt in the past five years. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample and 3 percentage points for those with current debt. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher.

Additional research was conducted by the Urban Institute, which analyzed credit bureau and other demographic data on poverty, race, and health status to explore where medical debt is concentrated in the U.S. and what factors are associated with high debt levels.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute analyzed records from a sampling of Chase credit card holders to look at how customers’ balances may be affected by major medical expenses.

Reporters from KHN and NPR also conducted hundreds of interviews with patients across the country; spoke with physicians, health industry leaders, consumer advocates, debt lawyers, and researchers; and reviewed scores of studies and surveys about medical debt.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Developing economies face their biggest set of challenges for years

Bruising week for managers as fears intensify over a global downturn

Wall Street braces for borrowing-cost rise not just next month but in September too as 8.6% rise in annual inflation spurs on central bank

The ghost of Paul Volcker is haunting Washington today after the US Federal Reserve announced it was stepping up the fight against inflation with an aggressive 0.75 percentage point increase in interest rates.

Four decades ago – the last time the annual increase in the American cost of living was higher than its current 8.6% – Volcker became legendary as the central banker who was prepared to drive the world’s biggest economy into deep recession to squeeze inflation out of the system.

Last month, The New Republic published an issue dedicated to the contemporary crisis of democracy at home and abroad. With articles ranging from a deep look into how Viktor Orbán has transformed Hungary into an autocracy to interviews with top commentators about what would happen if Donald Trump were to be reelected in 2024, the issue really ran the gamut of this (all too grim) waterfront.

On May 18, for a TNR Live event (video below), editor Michael Tomasky spoke with three of the issue’s contributors for their perspectives on the perilous state of democracy in the world today: David Rieff, a longtime TNR contributor and policy analyst; Barbara F. Walter, a political scientist at University of California, San Diego, and author of the acclaimed book How Civil Wars Start; and Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a historian at New York University, author of the acclaimed book Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, and frequent recent guest on MSNBC.

In his comments, Rieff discussed the erosion of democracy across the globe and whether a democratic resurgence is viable today. Despite Russia’s war in Ukraine, he sees China as a far larger threat to democracy than Vladimir Putin. Walter classifies the United States as an “anocracy,” falling somewhere between a democracy and autocracy—a society in which imagining a civil war is no longer far-fetched. And Ben-Ghiat spoke about the mystical bonds between strongmen and their followers, and chillingly described January 6 as a “leader-cult rescue operation.”

Tackling inflation requires reining in private markets—and embracing economic democracy.

The January 6 hearings fail to tackle the most important questions about the incident; they won’t hold anyone accountable; and most Americans have tuned them out. As political theater and a play for the midterms, they’re an opening night bomb.

Far-right protesters in front of the Capitol building on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Brett Davis / Flickr)

Not long after the Capitol riot in early 2021, I suggested four possible measures that among others would be practical, effective ways to respond to the incident and help prevent something like it from happening again: a comprehensive inquiry into the baffling law enforcement failure on the day; a nationwide investigation into police around the country and the extremists among them; steps to curb the power of corporate media monopolies, particularly on cable; and taking on the system of legalized bribery that had financed the right-wing figures behind the event and extremist movements more generally. A year later, I noted that nothing had been done about any of this, and in fact, in several cases, what had been done was to make all of these issues worse.

Now, six months after that, as Congress holds yet another series of hearings meant to be the absolute last, damning word on the episode, I’m tempted to write the same piece again.

It would be wrong to say that this latest set of hearings is a waste of time. The parade of Donald Trump lackeys and various Republican officials calling bullshit on the former president’s election fraud claims helps make the lie ever more untenable, though as always, anyone who bought into it in the first place will find a way to keep believing. And behind-the-scenes details about Trump’s behavior while the riot raged — including the alleged statement that protesters chanting “hang Mike Pence” might “have the right idea” — speak to the man’s extraordinary callousness and irresponsibility, not that we needed more evidence of that.

But for the most part so far, if you’ve consumed any of the previous January 6–related content out there, you already know what you’re going to get. The hearings have been little more than a reminder that the Capitol riot happened and that it was bad, only this time with a narrower focus on Trump and his personal role in the incident. A much-hyped compilation of never-before-seen footage of the day offers not a whole lot new from the hours upon hours of footage you would’ve already seen. Probably the most interesting pieces are the bird’s-eye shots, starting around the three-minute mark, that make it abundantly clear how badly unprepared the police were, a handful of officers being the only thing standing between the Capitol and a tidal wave of marchers.

We still don’t have any clue why that security failure happened, by the way, or why the copious warnings about the crowd’s size and plans were ignored. This is despite a Capitol police whistleblower accusing two high-ranking officials of profound failures that enabled what happened and saying that “the truth of the leadership/intelligence failures of the 6th is purposefully not being delivered to the officers and the public,” because the congressional community has “purposefully failed” to provide the truth.

It’s also in spite of knowing that at least one officer was sympathetic to the rioters and the fact that an after-action report the Capitol police produced identified serious intelligence failures, including a discrepancy between what the body’s hazardous response division was told — that there was the chance of violence and that protesters wanted to breach police lines — and what everyone else was told, which did not mention those possibilities. If the police had just prepared the same way they normally do for any other protest, the entire episode would likely have never happened, and yet this fundamental cause continues to go unexplored — deliberately, if you believe the whistleblower.

We also still haven’t gotten a national inquiry into extremism among the police and armed forces, even though 13 percent of those charged over entering the Capitol have backgrounds in one or the other, active duty in some cases. Corporate media, cable news in particular, still hasn’t faced the kind of reckoning for its role in spreading election disinformation that Congress has visited on, for instance, tech companies. And the broken political economy that helped make it all possible, and the role of economic dislocation in fomenting election delusions, is still untouched as a subject.

Even the extremely narrow focus of these particular hearings — holding Trump and his cronies to account — will come to nothing. Representative Bennie Thompson, the chair of the House select committee running these hearings, has explicitly said he won’t be making criminal referrals of anyone to the Justice Department.

That’s because the point of these hearings isn’t to actually solve anything but to serve as political theater that Democrats hope will give voters a reason to back them in this year’s midterms. There’s nothing wrong with political theater, of course. But the question is: is this actually useful political theater?

The ratings for the hearings have been respectable, even without coverage from Fox, but they’re lower than Joe Biden’s State of the Union address and don’t come close to the numbers that tuned into the Watergate hearings. More importantly, apart from Democrats, the US public just doesn’t really care that much. Instead, poll after poll after poll show it’s the economy, above all inflation, that’s most on voters’ minds.

The Democrats’ use of the hearings as an electoral tool shows that they’re well aware of the power of the bully pulpit they hold. Imagine if they had used it on something people cared about: hauling corporate profiteers before Congress and dressing them down over price gouging; calling in Amazon and other companies to testify about their union-busting efforts and worker mistreatment; summoning pharma executives to berate them about the extortionate prices they charge for drugs; or as Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) recently suggested the president should do, “bring the major oil companies in and tell them we’re going to have a windfall profits tax on what they’re doing in order to stop them from ripping off the American people.”

The Democrats have already held hearings like these in the recent past. Imagine if they were given the kind of blockbuster, prime-time attention right now that the January 6 hearings are getting, for which the party hired a TV executive to create the feel of a docuseries.

Instead, the January 6 hearings are the worst of all worlds: they won’t lead to anyone facing any consequences, don’t touch any of the lingering questions and underlying causes of the Capitol riot, and probably won’t make a hell of a lot of difference to the impending midterm bloodbath, since it’s largely only Democratic voters who afford the event this kind of importance. Democrats are correct that American democracy is in peril. But they clearly have no idea how to save it.

Joe Biden is old—79 years old now, he will be 82 when the next president is inaugurated in 2025. He is also underwater in the polls. According to FiveThirtyEight’s poll of polls, fewer than 40 percent of voters rate his presidency positively as of Monday; more than 53 percent disapprove. The Democratic Party is racing to an all-but-certain bloodbath in November’s midterm elections and is likely to lose control of both chambers of Congress. This means that the final two years of Biden’s presidency will be beset by baseless and intrusive investigations (if not impeachment on an endless scroll) and inertia. And none of that covers the worst inflation in decades, numerous geopolitical crises, and whatever other horrors the world unleashes between now and November 2024.

Biden can’t be stuck with all the blame. Much of his legislative agenda fell by the wayside thanks to the inability of Democratic lawmakers to resolve their own internecine negotiations. But Democrats are worried and for good reason. Biden’s age creates a not-unjustified impression that he may not be the ideal person to handle the myriad crises the United States is facing at the moment. Moreover, Biden’s unpopularity has been stubbornly constant—his approval rating has been on the decline for nearly a year. And so it is perhaps no surprise that a murmuration, over whether Biden’s the best choice to run for president in two years’ time, has begun.

Recent stories in New York and The New York Times capture this mix of angst and frustration. The Times noted the “challenges facing the nation mount” and described the party’s “fatigued base,” while observing that many party insiders “feel sorry for [Biden].” New York, meanwhile, set the scene in similar terms: “With Trumpism reascendant, ambivalence about Biden’s age and political standing is fueling skepticism just as the image of his understudy, Vice-President Kamala Harris, dips even further than his.” But while there’s little doubt that the Democrats and Biden are in deep trouble, there isn’t really a solid case to be made that the party should change horses—at least not with months before the midterms and years to go in Biden’s term.

Democrats couldn’t have predicted many of the crises that have caused the Biden presidency to flatline since late August of last year. The withdrawal from Afghanistan was much clumsier than it needed to be. But few foresaw the serious, prolonged threat of inflation—Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has only recently offered a mea culpa for her rosier predictions—and now that we’re in its grip, there aren’t many options at the disposal of a president to rapidly reverse the trend. Similarly, the scope of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was also difficult to envision before it kicked off, and the White House has done most of what could realistically be expected in response.

Even so, the big picture for Democrats is hardly shocking. Incumbent parties typically get trounced in the midterm elections, and 2022 will be no different. It is exceedingly rare for incumbent parties to gain ground in the midterm elections. In fact, since the start of the Civil War, it’s only happened twice and in moments of national crisis: Once in 1934 following the launch of the New Deal and again in 2002 after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Biden’s age, meanwhile, didn’t just emerge as a concern; it was a factor in the Democratic primary Biden won, and Donald Trump attempted to make Biden’s cognitive faculties one of the big election storylines when they faced off in the general election. Yes, Biden will be four years older in 2024—but so will we all, including the Republican Party’s most likely nominee, Donald Trump, who will be 78.

This recent boomlet of stories regarding the party making a big switch at the top of the ticket is a new, apocalyptic take on the age-old Democrats in disarray story. But this Chicken Little response to dampening political prospects is also normal.

But just because this storyline is emerging doesn’t mean it makes a lot of sense. Are there Democratic operatives lying around right now, happy to be the anonymous source for this kind of story? Sure. The bigger problem facing Democrats—and with anyone pitching the idea that Democrats should be looking for a successor—is that there really isn’t one on hand. After The New York Times makes mention of the deeply unpopular Harris, it gets to the bottom of a barrel rather swiftly:

These Democrats mentioned a host of other figures who lost to Mr. Biden in the 2020 primary: Senators Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, Bernie Sanders of Vermont, Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Cory Booker of New Jersey; Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg; and Beto O’Rourke, the former congressman who is now running for Texas governor, among others.

So that’s a bunch of people who already have the distinction of being beaten by Biden, some of whom fail to resolve the age issue that is supposedly a preeminent concern. New York’s roster, meanwhile, is more imaginative if also more far-fetched:

Governor Roy Cooper—the conference’s host, who had twice won North Carolina in the same years the swing state was carried by Donald Trump—was the most frequent topic of shadow-campaign chatter. Governor Phil Murphy, the New Jerseyan whose national ambitions are among Washington’s worst-kept secrets, was a close second. Also in heavy rotation, according to Democratic power brokers in the mix (and familiar with months of similar conversations): Governor J.B. Pritzker, the billionaire hotel-chain heir from Illinois, and Governor Jared Polis, the Coloradan with a mandate-light approach to COVID. When the conversation stretched into the bar, it lingered on Governor Gavin Newsom, who is coasting to reelection after defeating a recall attempt in California, and Governor Gretchen Whitmer, who knows from personal experience about the rising threat of white nationalism in Michigan.

Of all the candidates name-checked in the above roster of options, Sanders enjoys the most relative popularity—though he is a divisive figure within the party—and he’s even older than Biden. Murphy, meanwhile, only narrowly won reelection in New Jersey eight months ago, squeaking out a win over a relative unknown he was supposed to beat by double digits. Few have heard of Cooper, Pritzker, or Polis outside of their own states. The Democrats have boasted about the party’s deep bench, but the party doesn’t have a magic wand to simply anoint one of these figures the Chosen One. The idea of replacing Biden is just a fantasy. The idea that any one of these prospective candidates stands a better chance of beating Donald Trump may very well be as well.

And so the portrait that emerges is one that we’ve known for a while. Biden is old. The Democrats are going to get shellacked in the midterms. Their popular agenda didn’t pass because not enough Democrats supported it in the end. But no one really has any idea what might happen in the next two years, and what’s known isn’t enough to just toss Biden’s biggest strength, his incumbency, out the window, in favor of either a familiar candidate voters preferred less than Biden or an untested alternative yet to emerge on the scene. Regardless, Democrats should understand that there are few plausible scenarios in which swapping out Biden doesn’t get treated as a panicky decision. In theory, it may look like a justifiable move. In practice, it will be a world of hurt.