Archive for category: Uncategorized

Almost since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, epidemiologists, policymakers, science journalists, and many more have held onto two general assumptions that give them hope: that eventually enough people might develop immunity to Covid-19 to slow down transmission and that even if Covid doesn’t fade away, it might become a more seasonal illness, like respiratory viruses such as the flu, RSV, and other bugs—even other coronaviruses. But now, as cases rise steeply and summer approaches, Covid is again taking us by surprise.

There were some early signs that Covid might be different: While previous waves have reached their greatest peaks in winter, the virus also did significant damage in other seasons. And now, with the omicron wave, even more evidence is accumulating. While we’ve had two relatively calmer summers with regional spread, the relaxation of measures across the country seems to have triggered another surge, with nearly every state seeing an increase in Covid cases and hospitalizations.

“The wild card is the rise of variants,” Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told me over a year ago, when I asked him to predict what Covid would look like in 2022. How fast the virus would evolve would determine much about the next few years. Since then, variants have arisen that can evade our immune protections with startling efficiency. Even those who already suffered from cases of the first omicron variant in January or February are now reporting new cases of BA.2 or BA.2.12.1, two omicron subvariants in the United States that have quickly risen to dominance. While back in November 2020, one study suggested people who contracted Covid-19 and recovered might be immune to reinfection for years or even decades, it’s now clear that won’t be the case because of rapidly changing variants. People who recover from Covid-19 now can be reinfected in a matter of months.

With a virus that spreads year-round, is capable of reinfection, and is still evolving rapidly, and with few public protections still in place, we could be facing a future where we all get sick several times a year. Covid may stay with us for the foreseeable future, not as a seasonal threat but as a regular companion.

A future where people get Covid several times per year could have major implications for the immune-compromised and anyone seeking health care in a perennially stretched system. And it will ripple through schools and workplaces strained by illness. “It’s very disruptive to the functioning of society to have repeat surges and repeat infections with new variants every few months,” Abraar Karan, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford University, told me. Resurgences are “very, very disruptive—you’re still sick enough to be out of work, to have to be at home.”

Even before the pandemic, parents struggled to care for kids unexpectedly home from daycare and school with a seemingly endless array of viruses. People who didn’t have paid leave had to take unpaid time off from work, if they could, or work while they or loved ones were sick. Adding another virus to the mix, permanently and without any real off-season, could interrupt education and wreak professional and economic havoc.

Even once quarantine and isolation requirements are lifted, sick people will still need to stay home to recover, and parents will have to care for sick children. While omicron has been hailed as “milder”—a complicated concept already—a new preprint study that has not been peer reviewed or published indicates that omicron is just as severe as previous variants, including delta. Meanwhile, immunity from vaccines and prior infection is waning.

Medical care could also become infinitely more complicated. What happens for those seeking any type of care during a surge, when health systems are once again overwhelmed? What of patients with new diagnoses, new cancer treatments, new transplants—how will they navigate a system that, thanks to the desire of millions to get “back to normal,” is increasingly hostile to medically vulnerable people? This is an especially pressing question as millions of Americans are now grappling with long Covid.

Right now, two and a half years into the pandemic, there are still many questions without answers. How will we navigate a world with so much Covid spreading, if this is something like our steady state? What will multiple infections do to our bodies, our organs, our lives? And if this isn’t the future we want, what do we need to do to stop it? “That’s, of course, the question that everybody’s asking right now,” said Daniela Weiskopf, a research assistant professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology.

Adapting to constant Covid risk won’t be easy. “We have a strategy for flu,” Karan said, noting that influenza is more seasonal and less transmissible. Updated vaccines for the flu roll out right before it’s expected to rise each winter, helping to suppress severe illness and death. But with Covid, there’s no such strategy. “With Covid, we’re seeing something different, which is very fast mutations, large resurgences with new variants.”

And it’s not just its relative lack of seasonality that sets Covid apart—it also damages organs in ways we usually don’t see with respiratory viruses. There’s evidence that Covid affects the heart, lungs, brain, liver, and kidneys, possibly for years or even a lifetime. “We don’t know what the long-term effects are,” Karan said. And it is unclear now what repeat infection will do to our bodies. The recent shift to focusing on hospitalizations and deaths instead of cases could do a major disservice to those whose mild cases have long-term consequences, he said. “Given that we don’t know that, our policymakers and public health leaders should not be discounting the importance of cases.”

“As long as we allow uncontrolled spread, every time the virus infects somebody, it has a chance to mutate.”

The crystal ball is still cloudy on Covid’s future, even after years of learning about it. “We don’t know what the next variants are going to do. They could be more virulent. They could be more transmissible. They could be both,” Karan said. “We’re dealing with a lot of unknowns, and what we do know is that we are very vulnerable to having major disruption at minimum and potentially more hospitalizations and deaths, at worst, in the future.”

Even once we reach a steady state where Covid cases are more predictable, that doesn’t mean the virus won’t have severe implications. HIV is endemic. Malaria is endemic. Tuberculosis is endemic. Those viruses are still deadly—in fact, in some case, they’re growing deadlier as they evolve to survive.

“As long as we allow uncontrolled spread, every time the virus infects somebody, it has a chance to mutate,” Weiskopf said. “There is a possibility that new variants come up, and we do not know if they are milder or more severe.”

Every time Covid reveals a new surprise—that it spreads through the air, or it’s evolving more than expected, or emerging with surprising characteristics from unexpected sources—experts always come back to the same conclusion. At any point, we could choose to curtail this virus sharply, cutting off future mutations and tamping down the general uncertainty of the pandemic, or we could choose to continue believing that eventually it will just go away. We could use what we’ve learned to prevent future heartache, or we could allow the virus to keep leading the way—with plenty of middle ground in between.

The fact that we now are where we are—that Covid doesn’t seem to be weakening as people had hoped and seems to be getting better at evading vaccine protection—has a lot to do with policymakers deliberately choosing the low-investment path. But it still doesn’t have to happen this way. Our knowledge of how to prevent respiratory infections has grown exponentially; we have flattened cases of the flu and RSV to an astounding extent during previous rounds of the pandemic.

One of the most dangerous traps of understanding and responding to infectious disease is falling into binary thinking: Precautions are 100 percent effective, or they’re useless; Covid is over, or it’s everywhere.

“Even if we don’t eliminate Covid, we can still mitigate transmission,” Karan said. “We could do a lot better.” Tried-and-true prevention includes high-quality masks, ventilation, widespread and affordable testing and treatment, paid sick leave, and other support for caregivers and those who fall ill. “Those things matter,” Karan said. But “we have not been doing those. In fact, we’ve just abandoned a lot of that now.”

It is difficult to control disease only through individual behavior, and it’s hard to maintain, especially in the long term. Tools like condoms to prevent HIV or bed nets to prevent malaria can be extremely helpful for individuals navigating a risky environment, but systemic changes can matter even more. For Covid, that means strategies like updating vaccines, developing highly effective treatments, and improving ventilation in indoor spaces. “What if we increased air changes per hour in all public areas, with input from ventilation experts—could that significantly reduce the chance of airborne spread? That’s a really important question that the administration should really be focusing on,” Karan said.

And vaccines still matter. Although existing vaccines no longer offer the protection they once did, given new variants, they still help prevent severe illness in many people, particularly among those who receive boosters. “None of these variants we have seen so far has been able to completely evade our immune system,” Weiskopf said. While existing variants can evade antibodies, “all of them are recognized by our T-cells—the second line of our immune system,” she said. That’s what keeps an infection from progressing to severe illness. And the genes defining our T-cell response are the most diverse in all of the genes that the human body has, Weiskopf said—which means vaccines, even when they don’t prevent infection, will continue to help keep many of us safe.

Next-generation vaccines, like those inducing mucosal immunity, could stop infections in their tracks, which is why continuing to invest in our national Covid response is key. In the meantime, Weiskopf is researching how often we need boosters. “What we don’t know still today [is] what is the level of antibodies that we need—how high does the wall need to be, to make sure that people are protected from severe disease?” she said. Do you reach a plateau after, say, three shots, or do you need an annual immune reminder? Weiskopf puts it this way: “How long is your body able to keep the memory?”

Her words echoed in my ears. As I began work on this piece, the number of known U.S. Covid deaths officially passed one million. If 100,000 Covid deaths were an “incalculable loss,” what is 10 times greater than incalculable? Yet the memorials organized by local authorities or published by mainstream newspapers dropped quietly into a country where almost no mandates for precautions remain in place. Nationally, we have largely succumbed to the urge to move beyond the pandemic, even as it rages around us, a strategy that cannot continue forever.

How long will we keep the memory? The memory of everything and everyone we’ve lost, the memory of what worked to keep us safe and could still help us in the future, if only we remember what’s at stake. If we cannot or will not remember, the virus will continue reminding us every few months.

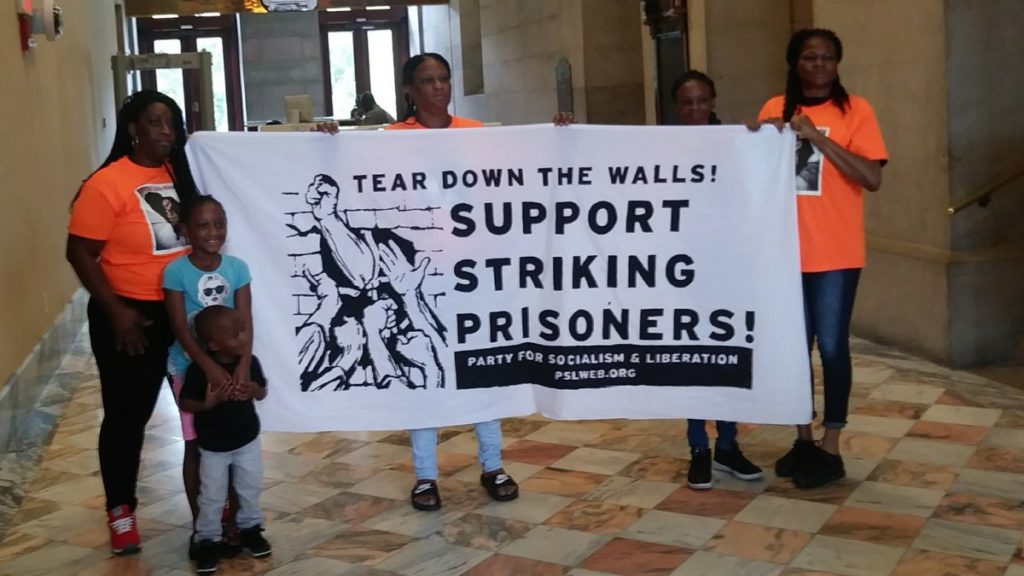

Just 41% of prison employees and 64% of prisoners are up to date on their vaccinations.

Just 41% of prison employees and 64% of prisoners are up to date on their vaccinations.

The post Court strikes down COVID vax mandate as COVID cases climb in California prisons appeared first on Liberation News.

The Squad and other progressives voted this week to ramp up the “war on terror” here at home. Right now, they might find it politically convenient to prop up draconian national security measures — but at some point, they’re going to have to take a stand.

Federal officers attempt to disperse racial justice protesters in Portland, Oregon, July 30, 2020. (Nathan Howard / Getty Images)

The post-9/11 “war on terror” was a disaster for Muslims and immigrant communities in the United States. Patriotic, law-abiding Muslim Americans were treated as foreign enemies and hundreds of immigrants were rounded up, detained, and deported. Americans’ constitutional rights were trampled while a sprawling system of mass surveillance took shape. Those brave enough to shine a light on its abuses were, at best, spied on and treated as criminals or, at worst, hounded into the poorhouse and even imprisoned and tortured. The only minor saving grace was that, technically, this “war” was never waged officially within the United States, where it could’ve led to even more alarmingly authoritarian outcomes.

That now seems to be changing under the Biden administration, which, ever since last year’s Capitol riot, has bit by bit ramped up a burgeoning domestic war on terror aimed at criminals and dissidents at home. The latest escalation in this budding campaign cleared the House on Thursday — and, horrifyingly, received the wholehearted backing of the congressional left.

Fast and Furious Bill Passage

The Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act of 2022 sailed through the House on a strict party-line vote, with not a single Democrat voting against and only one Republican, Illinois representative Adam Kinzinger, voting in its favor. Opposition to the bill was presumably considered politically toxic on the Left, as it was sold as a response to the racist mass murder committed in Buffalo last week, which is presumably why every single member of the “Squad” voted for it.

The legislation takes a tack similar to previous domestic anti-terrorism bills, making incremental additions to the terror-fighting strategy of US security apparatuses. The focus of this strategy now appears to be aimed at ostensibly homegrown extremists. The bill does not opt for the kind of sweeping overhaul we saw after the September 11 attacks.

The bill creates domestic terrorism offices within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Justice Department, and the FBI. These offices are all set to sunset in a decade. The heads of all three agencies must regularly issue a joint report on domestic terrorism threats, incidents, and arrests and prosecutions. The offices will direct their resources toward the threat categories with the highest number of instances. The bill also requires that they review and investigate hate crime charges with an eye on redefining or connecting them to domestic terror incidents.

The most defensible part of the bill is a section authorizing an interagency task force to “analyze and combat” white-supremacist infiltration of the armed forces and federal law enforcement. The effectiveness of this directive, however, remains to be seen. Although the bill’s language uses the term “combat,” it fails to spell out what this means. Its only specific details are in regard to the reports that federal agencies will be required to submit.

If the bill passes, it will represent at least some progress on a very serious and largely unaddressed problem. On the other hand, it also exposes the contradictory nature of progressives’, particularly the Squad’s, position on matters of civil liberties.

Still a Bad Idea

Joe Biden’s fledgling domestic war on terror has proven a tricky matter for left-wing lawmakers to navigate. The Left’s historical opposition to bigotry of all kinds made it somewhat less fraught for elected progressives to push back against the original “war on terror,” given its tendency to demonize and target Muslims and immigrants.

But ever since the national security state shifted its public-facing rhetoric around terrorism from Islamic extremists to far-right ones — and with progressives now tending to frame issues around the concept of “white supremacy” more and more — the congressional left has become increasingly quiet on the issue. After all, what progressive wants to look like they’re soft on literal Nazis?

But there are good reasons they should push back. For one, the leading progressive concerns about the license granted to the state by the original war on terror remain with this version of the bill. The powers authorized by this legislation can easily be turned on anyone — not simply the odious groups that are invoked for the bill’s passage.

The Biden administration’s official domestic counterterrorism strategy explicitly “makes no distinction based on political views” and name-checks supposed domestic terrorists motivated by a “range of ideologies,” including animal rights, environmentalism, anarchists, and anti-capitalists. In practice, the FBI has already imprisoned one Florida anarchist over what amounted to a series of public social media posts. Domestic terrorism prosecutions have exploded since 2020, now far outnumbering cases defined as international terrorism, and many of those have been racial justice protesters that the Biden administration has continued to prosecute as terrorists.

Even if, despite all this, one believes that a Democratic administration can be trusted to responsibly pursue a domestic “war on terror,” we would do well to remember that the United States is a two-party democracy where power regularly changes hands. Are progressives happy to hand ever-growing national security powers to Donald Trump, who mobilized the DHS for a campaign of repression against the George Floyd protests? Would they be comfortable entrusting them with Ron DeSantis, who just passed yet another law attacking protest rights, this time banning pickets outside private homes? Do they trust GOP-appointed federal agencies not to fudge the numbers and steer prosecutions toward threat categories that aren’t related to the far right?

Juicing the Steroidal Security State

Beefing up law enforcement and security powers is an understandable response to horrors like Buffalo, but there’s not much evidence that the increase of these powers will succeed as measures of prevention as the bill’s sponsor claims. Attacks like this are happening on a depressingly regular basis even though the United States is already operating the largest, most expensive national security bureaucracy in its history. Such attacks have continued, even in the teeth of the country’s vast surveillance state that effectively sweeps up and stores information about the private activities of most adults. This is the very same surveillance state that has already given the FBI sweeping authority to go after whoever it defines as extremists — which it has mostly used to, again, go after racial justice activists. This is largely why only a few years ago, both leftists and liberals rejected the idea of passing a domestic terror statute in the wake of the horrific El Paso shooting.

Given the long record of the FBI and federal agencies like the DHS targeting vulnerable communities, activists, and dissidents more generally — and given the Bureau’s copious recent use of far-right extremists as informants to target left-leaning protesters — does it really make sense to believe they’ll use these new authorities as progressives intend? It’s a bit of a glaring contradiction that the same bill that treats federal law enforcement as the leading instrument against far-right extremists is also concerned with its infiltration by white supremacists.

The Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act of 2022 is not as bad as it could have been. To some extent, it’s lucky that Biden’s domestic war on terror has so far been fairly incremental. But as more tragedies like Buffalo pile up — and as politicians continue to do nothing about the availability of guns or the root causes that drive people toward this kind of hatred and violence in the first place — pressure will build to ramp things up.

Right now, progressives like those of the Squad may find it politically easier go along with something that, judging by their past public statements and positions, they quietly know is a bad and dangerous idea. But at some point, they’re going to have to take a stand. And if they don’t, they’ll risk hurting the very communities and political movements they’re fighting for.

If the global economy comes crashing down as many pundits are predicting, it is good to know there are viable alternatives.

This is part two to a May 4, 2022 article called “A Monetary Reset Where the Rich Don’t Own Everything,” the gist of which was that national and global debt levels are unsustainably high. We need a “reset,” but of what sort? The “Great Reset” of the World Economic Forum (WEF) would leave the people as non-owner tenants in a feudalistic technocracy. The reset of the Eurasian Economic Union would allow participating nations to opt out of the Western capitalist system altogether, but what of the Western countries that are left? That is the question addressed here.

Our Forefathers Had Some Innovative Solutions

Fortunately for the United States, our national debt is in U.S. dollars. As former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan once observed, “The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default.”

Paying government debt by just printing the money was the innovative solution of the cash-strapped American colonial governments. The problem was that it tended to be inflationary. The paper scrip they issued was considered an advance against future taxes, but it was easier to issue the money than to tax it back, and over-issuing devalued the currency. The colony of Pennsylvania fixed that problem by forming a government-owned “land bank.” Money was issued as farm credit that was repaid. The new money went out from the local government and came back to it, stimulating the economy and trade without devaluing the currency.

But in the mid-eighteenth century, at the behest of the Bank of England, the colonies were forbidden by King George to issue their own currencies, triggering a recession and the American Revolution. The colonists won the war, but by the end of it the currency was so devalued (chiefly from British counterfeiting) that the Founding Fathers were afraid to include the power to issue paper money in the Constitution.

Hamilton’s Solution: Debt-for-equity Swaps

That left Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in a bind. After the war, the colonies-turned-states were heavily in debt, with no way to repay it. Hamilton solved the problem by turning the states’ debts into equity in the First United States Bank. The creditors became shareholders in the bank, earning a 6% dividend on their holdings.

Might that work today? H.R. 3339, a bill currently before Congress, would form a National Infrastructure Bank (NIB) modeled on Hamilton’s U.S. Bank, capitalized with federal securities acquired in debt-for-equity swaps. Shareholders would receive a guaranteed 2% dividend on non-voting preferred stock in the bank, with the option of recovering the principal after 20 years.

If the whole $30 trillion U.S. federal debt were turned into bank capital, leveraged into loans at 10 to 1 as banks are allowed to do, the bank could do $300 trillion in infrastructure loans. To start, the Federal Reserve could buy NIB stock with the $5.76 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities currently on its balance sheet, capitalizing potential loans of $57 trillion. The possibilities are breathtaking; and because the money would enter the money supply in the form of low-interest loans to local governments that would be paid back over time, the result need not be inflationary. Loans for infrastructure and other productive ventures would raise supply to meet demand, keeping prices stable.

Lincoln’s Solution: Just Issue the Money

Hamilton’s solution to an unsustainable federal debt was terminated when President Andrew Jackson closed down the Second U.S. Bank. That left Abraham Lincoln in a bind. Faced with a massive debt at usurious interest rates to fund the Civil War, he solved the problem by reverting to the solution of the American colonists: just issue the currency as paper money.

In the 1860s, these U.S. Notes or Greenbacks constituted 40% of the national currency. Today, 40% of the circulating money supply would be $7.6 trillion. Yet massive Greenback issuance during the Civil War did not lead to hyperinflation. U.S. Notes suffered a drop in value as against gold, but according to Milton Friedman and Anna Schwarz in A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, this was due not to “printing money” but to trade imbalances with foreign trading partners on the gold standard. The Greenbacks aided the Union not only in winning the war but in funding a period of unprecedented economic expansion, making the country the greatest industrial giant the world had yet seen. The steel industry was launched, a continental railroad system was created, a new era of farm machinery and cheap tools was promoted, free higher education was established, government support was provided to all branches of science, the Bureau of Mines was organized, and labor productivity was increased by 50 to 75 percent.

The Japanese “Free Lunch”

Another option is for the U.S. government to “monetize” its debt by having the central bank purchase and hold it or write it off. The Federal Reserve returns interest and profits to the Treasury after deducting its costs.

This alternative, too, need not be inflationary, as has apparently been demonstrated by the Japanese. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) started buying government bonds in 1999, after reducing interest rates to zero, then dropping them into negative territory in 2015. Today Japan’s government debt is a whopping 260% of its Gross Domestic Product, and the Bank of Japan owns half of it. (Even the outsized U.S. debt to GDP ratio is only 126%.) Yet annual inflation is now only 1.2% in Japan, not even up to the BOJ’s longstanding 2% target. To the extent that prices are rising, it is not from money-printing but from lockdowns and supply chain disruptions and shortages, the same disruptions triggering price inflation globally.

Hedge fund manager Eric Peters discussed the Japanese experiment in a recent article titled “Can a Modern Nation Pull Off a Debt Jubilee Without Full Monetary Collapse?” Noting that “core prices in Japan’s economy remain almost identical today as they were when its zero-interest-rate experiment began,” he asked:

Could the central bank create money, buy all the outstanding bonds, and simply burn them? Execute a modern version of an Old Testament debt Jubilee? …. [M]ight it be possible for a country to pull off such a feat without full monetary collapse? We don’t know, yet.

A Treasury Issue of Special Coins or E-cash

For future budget expenses, rather than borrowing, the government could follow President Lincoln and just issue the money it needs. As Thomas Edison observed in the 1920s:

If the Nation can issue a dollar bond it can issue a dollar bill. The element that makes the bond good makes the bill good also. The difference between the bond and the bill is that the bond lets the money broker collect twice the amount of the bond and an additional 20%.

When the Constitution was ratified, coins were the only officially recognized legal tender. By 1850, coins made up only about half the currency. The total face value of all U.S. coins ever produced as of January 2022 is $170 billion dollars, or less than 0.9% of a $19 trillion circulating money supply (M2). These coins, along with about $25 million in U.S. Notes or Greenbacks, are all that is left of the Treasury’s money-creating power. As the Bank of England has acknowledged, the vast majority of the money supply is now created privately by banks as deposits when they make loans.

In the early 1980s, a chairman of the Coinage Subcommittee of the House of Representatives observed that the Constitution gives Congress the power to coin money and regulate its value, and that no limit is put on the value of the coins it creates. He said the government could pay off its entire debt with some billion dollar coins. In a 2007 book called ”Web of Debt,” I wrote about this and said in today’s America it would have to be trillion dollar coins.

In 1982, Congress chose to choke off this remaining vestige of its money-creating power by imposing limits on the amounts and denominations of most coins. The one exception was the platinum coin, which a special provision allows to be minted in any amount for commemorative purposes (31 U.S. Code § 5112). In 2013, Georgia attorney Carlos Mucha proposed issuing a platinum coin to capitalize on this loophole, in order to solve the gridlock then in Congress over the debt ceiling. Philip Diehl, former head of the U.S. Mint and co-author of the platinum coin law. He said:

In minting the $1 trillion platinum coin, the Treasury Secretary would be exercising authority which Congress has granted routinely for more than 220 years . . . under power expressly granted to Congress in the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8).

Prof. Randall Wray explained that the coin would not circulate but would be deposited in the government’s account at the Fed, so it would not inflate the circulating money supply. The budget would still need Congressional approval. To keep a lid on spending, Congress would just need to abide by some basic rules of economics. It could spend on goods and services up to full employment without creating price inflation (since supply and demand would rise together). After that, it would need to tax — not to fund the budget, but to shrink the circulating money supply and avoid driving up prices with excess demand.

A more modern option is for the Treasury to issue “e-cash,” an electronic form of cash transferred on secure hardware not requiring an internet connection. The ECASH Act, H.R. 7231, introduced on March 28, 2022 by Rep. Stephen Lynch, “directs the Secretary of the Treasury to develop and introduce a form of retail digital dollar called ‘e-cash,’ which replicates the off-line-capable, peer-to-peer, privacy-respecting, zero transaction-fee, and payable-to-bear features of physical cash….”

Unlike the central bank digital currencies now being developed by central banks globally, e-cash would be anonymous and not traceable, having all the privacy attributes of physical cash. Various models are in development, including one already introduced in China in 2021, an offline-capable smart payments card that was part of the government’s digital yuan rollout.

A People’s Reset

Those are alternatives for relieving the government’s debt burden, but what about the massive sums in student debt, medical debt, and rent and mortgage payments now in arrears? Biden promised in his presidential campaign to forgive student debt or some portion of it. But whether this can legally be done by presidential order, without congressional approval, is controversial. Arguments have been made both ways.

For most student debt, however, the creditor is actually the Department of Education, a cabinet-level department established by Congress with some limited power to cancel debt. In August 2021, for example, the Department canceled the student debt of the disabled. Congress itself could also write off the debt. The challenge is getting agreement on which debts to cancel and by how much.

What of the student debt, mortgage debt, and credit card debt held by private banks? Private banks have a contractual right to repayment. They also have an obligation to balance their books, meaning they could go bankrupt if unable to collect. But as British economist Michael Rowbotham observed, these debts too could be written off if the accounting standards were changed. Banks don’t actually lend their own money or their depositors’ money. The money they lend is created simply by writing the borrowed sums into the deposit accounts of their customers, so voiding out the debts would be cost-free. The accounting standards would just need to be changed so that the books would not need to balance. The debts could be carried as nonperforming loans or moved off the books in special purpose vehicles, as the Chinese have been known to do with their nonperforming loans. As for which debts to write off and by how much, that is a policy question for legislators.

Would that sort of debt jubilee be inflationary? Yes, to the extent that students and other debtors would have money to spend from their incomes that they did not have before, money that would be competing for a limited supply of goods and services. Again, however, inflation could be avoided by powering up the production of goods and services sufficiently to meet demand.

That means powering up small and medium-sized businesses, which generate most local productivity and employment; and that means providing them with affordable credit. As UK Prof. Richard Werner observes, big banks don’t lend to small businesses. Small banks do, and their numbers are rapidly shrinking. A national infrastructure bank could do it but would have trouble making prudent loans for businesses and farms across the country. The Soviet Union tried that and failed. Prof. Werner proposes instead to form a network of local public, cooperative and community banks.

Arguably, local publicly-owned banks could also be capitalized with debt-for-equity swaps, using the ballooning state bond debts. We have plenty of debt to go around! A network of state-owned public banks on the model of the Bank of North Dakota would be good.

Other Options

To the extent that taxes are needed to balance the money supply, a land value tax (LVT) would go far toward replacing income taxes, without taxing labor or productivity. See “Pennsylvania’s Success with Local Property Tax Reform” in the book “Earth Belongs to Everyone” by Alanna Hartzok. An LVT excludes physical structures (e.g. houses) and taxes only the value of the land itself, including the natural resources on and under it. It thus returns to the public a portion of any appreciation in value due to public works (new schools, subway stops, etc.), without taxing improvements made by the property owners themselves. It helps curb land hoarding and speculation, and ensures that land sites are put to good use.

Independent community currency and cryptocurrency systems are other possibilities for circumventing debts in the national currency, but those topics are beyond the scope of this article.

In any case, if the global economy comes crashing down as many pundits are predicting, it is good to know there are viable alternatives to the technocratic feudalism of the WEF’s Great Reset. In his 2020 book “The Great Reset,” WEF leader Klaus Schwab declared that the COVID-19 pandemic “represents a rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, reimagine and reset our world,” making way for a polycentric technocracy. It is also a rare opportunity for us to implement an alternative system with a mandate to serve the people. We might call it the People’s Great Reset.

Ellen Brown

Web of Debt

This article was first posted on ScheerPost.

“Attention, MOVE. This is America. You have to abide by the laws of the United States.” This was the ultimatum given through a Philadelphia police megaphone to a group of Black activists trapped in their home in the early morning of 13 May 1985.

Pennsylvania Democratic congressional candidate, state Rep. Summer Lee, talks to the press in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. | Nate Smallwood/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Democratic voters are moving their party to the left — and dragging candidates with them.

This year’s Democratic primaries are being largely framed as an ideological struggle between the national party’s moderate and progressive wings. But voting patterns over the last few weeks have complicated that narrative.

In marquee contests in Pennsylvania and Oregon, progressive wins led to proclamations that the left wing of the party is gaining influence, while some moderate victories defied that thinking. What’s becoming clear as votes are counted, however, is that Democratic primary voters seem to care less about who the “progressive candidate” is and more about if candidates are campaigning on progressive goals. What many of the Democrats who won this week have in common is that they all embraced progressive priorities tailored to where they were running.

Perhaps nowhere encapsulated this reality better than swing-state Pennsylvania, where a relatively progressive and locally trusted candidate who repeatedly rejected the progressive label — Lt. Gov. John Fetterman — trounced the more moderate, Washington favorite, Rep. Conor Lamb, in the primary race for the US Senate.

“Just being a centrist anymore, it’s hard to get things done. There’s shrinking room left in the middle,” Mustafa Rashed, a Democratic strategist in Philadelphia, told me about the state’s dynamics.

Around the state, candidates who delivered digestible versions of progressive messages did well, from the left-leaning candidates who won races in heavily Democratic areas for state and federal legislatures to the moderate incumbents who survived tough challenges from the left. In nearly all of these races, a general shift to the left was apparent among the party’s base and candidates.

This trend isn’t necessarily universal: Plenty of more traditional moderate Democrats won their races in Ohio and North Carolina. And it’s possible upcoming races in California, Illinois, Michigan, and Texas may upset this narrative. But for the most part, the primaries so far appear to show that progressive activism and ideas have changed what primary voters want and what their candidates are offering.

Every team scored wins on Tuesday

Both sides of the Democratic ideological spectrum could claim wins on Tuesday. From North Carolina to Oregon, there wasn’t uniformity in who emerged victorious.

What does tie a lot of Tuesday’s races together, though, is how few moderates ran openly down the middle of the ideological spectrum without co-opting at least some of the issues and language progressives have used in previous races. That includes things like advocating for a higher minimum wage, expanding health care access and coverage, more openly embracing gun control and abortion rights, and at least addressing climate change.

A more moderate, establishment type prevailed in Pennsylvania’s Third Congressional District, where Rep. Dwight Evans beat back progressive challengers by focusing on affordable housing, criminal justice reform, gun violence, and crime. A similar dynamic could be seen in other seats in the state legislature, including with longtime state Sen. Anthony Williams, who campaigned on abortion access, gun-violence prevention, and criminal justice reform as he faced his first serious challenge from the left. And in the primary for lieutenant governor, frontrunner Rep. Austin Davis defeated rivals to his left running on abortion and criminal justice reform.

This trend wasn’t just seen in Pennsylvania.

In Kentucky, liberal state Senate Minority Leader Morgan McGarvey defeated a lefty rival to represent the Louisville-area Third Congressional District, which is solidly Democratic, by supporting partial student loan cancellation, single-payer health care, and endorsing the idea of a Green New Deal.

In North Carolina, a similar picture emerged. Centrist-minded state Sen. Don Davis, backed by outgoing US Rep. GK Butterfield, comfortably beat his progressive challenger, a former state senator endorsed by US Sen. Elizabeth Warren and an array of progressive groups. Though Davis doesn’t back a Green New Deal or Medicare-for-all, he still campaigned on affordable health care, voting rights, reproductive rights, and increasing the minimum wage.

Things were a little different in Democrat-dominated Oregon, however, where progressives were ascendant. The solidly centrist incumbent Rep. Kurt Schrader, who campaigned on pragmatism and consensus-building, is on track to lose to progressive activist Jamie McLeod-Skinner in the Fifth District, while crypto-backed lawyer Carrick Flynn, who had no political experience, is also trailing the progressive state Rep. Andrea Salinas. And after a difficult campaign, former state House Speaker Tina Kotek defeated a moderate challenger, state Treasurer Tobias Read, in the primary for Oregon governor.

Oregon’s results, which saw voters gravitate toward the conventional, genuine progressive, add another layer of complexity to the primary picture. Regardless, races this week showed Democratic candidates of all ideologies feel compelled to address their left flank.

Progressive ideas have changed the way candidates run

A lot has changed since the last midterms in 2018, when progressives made big gains but moderate Democrats were instrumental in giving the party a majority in the House. So far, the party’s primaries are showing an electorate much more willing to accept populist, progressive(-ish) ideas than before — a big win for left-wing activists and thinkers who have managed to move the party’s ideological center in their direction.

Few candidates so far have run overtly as centrists without at least paying lip service to progressive priorities. Where they refused to do so, as in Schrader’s race, they faced headwinds from a changing Democratic primary electorate.

“Ten years ago, blue-dog and corporate Democrats would run on that [centrist] message against progressives,” Adam Green, the co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, which has endorsed several progressive upstarts this election cycle, told me. “These days, they’re more willing to use the language of progressives against progressives in primaries — but Schrader was the exception to this rule.”

That’s not to say a moderate using progressive talking points has a sure path to success. Marcia Wilson, the chair of rural Pennsylvania’s Adams County Democratic Party, said Lamb’s campaign showed how some Democrats fear electing an apparent liberal who turns out to be a Joe Manchin-style Democrat.

“Democrats are feeling more galvanized and want to be known as Democrats, not because they are unwilling to compromise but because we want to support Democratic ideals,” she said. Wilson told me that partly explains why Lamb’s pitch to the state didn’t resonate — a more conservative background and platform in past races made his leftward shift in the Senate primary seem inauthentic.

But still, Lamb attempted some ideological change. A similar thing happened in earlier Democratic primaries in Ohio, where more moderate candidates like Tim Ryan (in the state’s Democratic Senate race), Nan Whaley (in the governor’s race), and Shontel Brown (in the 11th Congressional District) were pushed to the left. Upcoming races will test this trend, but so far, it appears Democratic voters want their candidates to speak like progressives, even if they aren’t actually progressive.

The general election may in turn change the way these candidates talk about their priorities. The citizens who typically turn out to vote in November tend to be less ideological and party-affiliated than the voters who participate in primary elections. And the progressive ideals beloved by hardcore Democrats may not be as well received by moderates and centrists in competitive general election seats.

If progressives — and progressive ideas — do win uphill battles in these swing districts, however, Democrats may end up with a newly empowered left flank, catalyzing the political polarization Americans have come to expect from their government.

Until a few decades ago, most Democrats did not hate Republicans, and most Republicans did not hate Democrats. Very few Americans thought the policies of the other side were a threat to the country or worried about their child marrying a spouse who belonged to a different political party.

All of that has changed. A 2016 survey found that 60 percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans would now balk at their child’s marrying a supporter of a different political party. In the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, the Pew Research Center reported that roughly nine out of 10 supporters of Joe Biden and of Donald Trump alike were convinced that a victory by their opponent would cause “lasting harm” to the United States.

[Kori Schake: The U.S. puts its greatest vulnerability on display]

As someone who lived in many countries—including Germany, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom—before coming to the United States, I have long had the sense that American levels of partisan animosity were exceptionally high. Although I’d seen animosity between left and right in other nations, their hatred never felt so personal or intense as in the U.S.

A study just published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace confirms that impression. Drawing on the Variety of Democracies (V-Dem) data set, published by an independent research institute in Sweden that covers 202 countries and goes back more than two centuries, its authors assess to what degree each country suffers from “pernicious” levels of partisan polarization. Do their citizens have such hostile views of opponents that they’re willing to act in ways that put democracy itself at risk?

The authors’ conclusion is startling: No established democracy in recent history has been as deeply polarized as the U.S. “For the United States,” Jennifer McCoy, the lead author of the study and a political-science professor at Georgia State University, told me in an interview, “I am very pessimistic.”

On virtually every continent, supporters of rival political camps are more likely to interact in hostile ways than they did a few decades ago. According to the Carnegie study, “us versus them polarization” has been increasing since 2005. McCoy and her colleagues don’t try to explain the causes, though the rise of social media is obviously a contributing factor.

As near-universal as political polarization has become, it is more pronounced in some places than in others. On a five-point scale, with 0 indicating a country with very little partisan polarization and 4 indicating a country with extreme polarization, both the U.S. and the rest of the world, on average, displayed only a modest degree of polarization at the turn of the millennium: They each scored about a 2.0. By 2020, the world average had increased significantly, to a score of about 2.4. But in the United States, polarization accelerated much more sharply, growing to a score of 3.8.

Among countries whose political institutions have been relatively stable, the pace and extent of American polarization is an eye-popping outlier. “Very few countries classified as full liberal democracies have ever reached pernicious levels,” the study’s authors write. “The United States stands out today as the only wealthy Western democracy with persistent levels of pernicious polarization.” When I spoke by phone with McCoy, she was even more categorical: “The situation of the United States is unique.”

[From the May 2022 issue: Why the past 10 years of American life have been uniquely stupid]

To live in a country where political disagreements turn into personal vendettas is no fun, but a growing body of research reveals more systemic effects. Pernicious polarization makes good-faith efforts to tackle social problems such as public-health crises harder and bad-faith efforts to turn them into political gain easier. At worst, an erosion of trust in democratic norms and political institutions can end up as political violence and civil war.

The fundamental premise of democracy is that citizens agree to be ruled by whoever wins an election. But if many citizens come to believe that letting the other side rule poses a threat to their well-being, even their lives, they may no longer be willing to accept the outcome of an election they lose. This makes it easier for demagogues to attract fervent supporters, and even to turn them against a country’s political institutions. The January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol is just such a symptom of the malaise.

We might hope that the history of other nations would offer clues to how the U.S. could get its polarization under control. The past century has yielded notable cases of “depolarization,” from Italy in the 1980s to Rwanda in the early 2000s. In Italy, escalating political violence from both the far left and the far right had threatened to tear the country apart, but leaders from rival political parties eventually united against terrorism, and that enabled the country to weather the crisis. In 1990s Rwanda, Hutus murdered hundreds of thousands of Tutsis in an orgy of genocidal violence, yet the country has achieved a modicum of national reconciliation and managed to keep the peace (though at the price of Paul Kagame’s autocratic leadership). Do examples like these contain any useful lessons for the U.S.?

Unfortunately, the data in the Carnegie study do not offer much cause for optimism. About half of the time a country experienced serious polarization since 1900, mutual distrust and hatred turned into a permanent condition. Although political tensions waxed and waned, these countries never fell below the level of pernicious polarization for any extended period. And many countries never recovered. Once pernicious polarization has set in, it stays.

That leaves the other half of cases. Those don’t offer much hope, either. Many of the supposed success stories saw either a relapse into dangerous levels of polarization or merely a moderate degree of depolarization. And when a country did manage to depolarize in a lasting way, a major political disaster seemed needed to force it: a civil war, a cruel dictatorship, or a struggle for independence. Only after overcoming such dire turmoil did these countries escape their vicious cycles. “The prevalence of systemic shocks in bringing about depolarization,” the study’s authors note, “was especially striking.”

That no such systemic shock has struck the U.S. in modern history would seem to bode ill for American prospects of depolarization. But do things really have to fall apart before we can put them back together?

The state of America’s union is especially fractious, true, but our predicament may not be quite as dire as it seems. The limitations of the Carnegie study itself illustrate why we should take predictions of doom with a grain of salt.

The survey’s polarization data are ambitious in scope—aggregating 120 years of historical information about a large number of countries—but the methodology behind them is more modest. The V-Dem data set used in the Carnegie study relies on asking a group of from five to seven country experts a single question about any given nation: “To what extent is society divided into mutually antagonistic camps in which political differences affect social relationships beyond political discussions?” If the experts answer that this is the case to a “noticeable extent,” with supporters of opposing camps “more likely to interact in a hostile than friendly manner,” this counts as a 3, on a scale of 0 to 4. That score is enough to qualify as “pernicious polarization.” What’s more, this assessment is highly retrospective: How polarized America was in, say, 1935, or in 1968, or in 1999 is a judgment made by a handful of social scientists only recently. Quantifying polarization like this is susceptible to distortion in two ways: presentism and provincialism.

[Adam Serwer: The myth that Roe broke America]

Experts evaluating how polarized America has been in the past century might remember every detail of a shouting match with a Trumpy uncle at last year’s Thanksgiving, but they cannot possibly have such a visceral feel for political divisions in, say, the 1910s, however much they’ve read about the period. That risks presentism. With their personal experience of partisan conflict and the shrill tone on social media top of mind, they may overestimate how much partisan hatred there is today and underestimate how much partisan hatred there was in the past.

“Expert surveys are subjective,” McCoy admitted when I put this concern to her. “There is no way of getting around that.”

What’s more, these experts will surely have different cultural assumptions about what constitutes a hostile political interaction. This—the danger of provincialism—makes comparisons among countries more difficult. In America, what is salient is how much nastier and more aggressive political discourse has become in recent decades. But in a society that recently experienced civil war, what may be more salient is that people are now willing to disagree about politics without killing one another. That perceptual gap between what counts here and what counts there could lead experts to assess a comparatively peaceful country that has become more sharply divided, like the U.S., as more polarized than a war-ravaged country that is somewhat less divided than it used to be.

In many of the countries that have experienced pernicious polarization, partisan political identity aligns almost perfectly with visible markers of ethnic or religious identity. In Lebanon and Kenya, for example, it is enough to see or hear a person’s name to know which way they’re likely to vote. When polarization spikes in these places, supporters and opponents of a political candidate don’t just yell at each other; they withdraw from all social cooperation, and their animosity grows vengeful and deadly.

“If you work for the Croat Catholic fire department,” Eboo Patel, a prominent interfaith leader, writes about Mostar, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, “you don’t respond to the burning buildings of Bosnian Muslims, even if you happen to be closer. And if you work for the Bosnian Muslim fire department, you let the flames engulf Croat Catholic homes.”

America’s polarization clearly differs from the Bosnian example—which experts actually scored as significantly lower than the United States’ (at 3.2 out of 4)—in two crucial ways. First, the overlap between partisan polarization and divisions of race, class, or religion is at best imperfect in the U.S. Although demographic patterns do offer clues to the likelihood of people’s support for Democrats or Republicans, a significant number of Latino Americans vote for the Republican Party and a lot of white Americans vote for the Democratic Party. Second, in many spheres of American life—including the workplace and Little League games—people put aside political differences or may not even be aware of them. And the local fire department does not ask for your voter registration before deciding whether to put out your house fire.

Perhaps America is not so much uniquely polarized as polarized in a unique way. Fifty years ago, out-group hatred in the United States primarily involved race and religion: Protestants against Catholics, Christians against Jews, and, of course, white people against Black people. Most Americans did not care whether their children married someone from a different political party, but they were horrified to learn that their child was planning to “marry out.”

[Read: The bipartisan group that’s not afraid of partisanship]

Today, the number of Americans who oppose interracial marriage has fallen from well over nine in 10 in 1960 to far less than one in 10. And as the rapid increase in the number of interracial babies shows, this is not just a matter of people’s telling pollsters what they want to hear. In contrast to the dynamic in other deeply polarized societies, the division in America between opposing political camps revolves less around demographics and more around ideology.

A host of recent social-science studies backs this up. In one experiment, a sample of Americans was asked to award scholarships to fictitious high-school students. Presented with a candidate’s résumé suggesting that the applicant was of a different racial group from theirs, the subjects engaged in surprisingly little discrimination. (In fact, Americans of European descent tended to favor, not discriminate against, African American candidates.) But presented with a résumé that suggested the applicant had a different political-party affiliation from theirs, the subjects had a strong tendency toward bias: When choosing between similarly qualified scholarship candidates, four out of five Democrats and Republicans favored an applicant who belonged to the same political party.

Even as American politics got nastier in recent years, the overlap between ethnic identity and partisan polarization has actually continued to weaken. Trump was competitive in the 2020 election in part because he significantly increased his 2016 share of the vote among Black, Asian-American, and especially Latino voters. And Biden won appreciably more white voters than Hillary Clinton did. In other words, a voter’s racial identity was much less predictive of voting behavior in 2020 than it was in 2016.

Jennifer McCoy affirmed this, when I asked her about the difference between the United States and other perniciously polarized democracies: “Unlike many other polarized democracies, we are not a tribal country based on ethnicity … The key identity is party, not race or religion.”

America’s uniqueness could allow a more hopeful story than the headline findings of the Carnegie report might suggest. If polarization is mainly a matter of partisan political identities, the problem may be easier to solve than divisions based on ethnic or religious sectarianism.

One approach that could alleviate polarization in the U.S. is institutional reform. Right now, many congressional districts are gerrymandered, shielding incumbents from competitive primaries while making them hostage to the extremist portion of their base. Some states have attenuated this problem by taking districting out of party control. But other measures, such as adopting the single transferable vote or creating multimember districts, could also shift political incentives away from polarization.

California has already adopted a small-seeming—and thus realistic—innovation. In so-called jungle primaries, candidates from all parties compete in the election’s first round; then the top two finishers face off in the second-round general election. As a result, moderates with cross-party appeal get a fighting chance at being elected. If this can work in deep-blue states like California, it can work in deep-red states like Alabama.

Soothsayers of doom are in demand for a reason. American partisan polarization has, without a doubt, reached a perilous level. But America’s comparative competence at managing its ethnic and religious diversity, which has so far ensured that partisan political identities do not neatly map onto demographic ones, could be a saving grace.

We urgently need visionary leaders and institutional reforms that can lower the stakes of political competition. Imagining what a depolarization of American politics would look like is not too difficult. The only problem is that America’s political partisans may already hate one another too much to take the steps necessary to avoid catastrophe.

Still, fringe candidates are luring GOP voters and winning key races.

The Republican Party’s radical right flank is making inroads among voters and winning key primaries east of the Mississippi. But out West, among the five states that held their 2022 primary elections on May 17, a string of GOP candidates for office who deny the 2020’s presidential election results and have embraced various conspiracies were rejected by Republicans who voted for more mainstream conservatives.

In Pennsylvania, Douglas Mastriano, an election denier and white nationalist, won the GOP’s nomination for governor. He received 587,772 votes, which was 43.96 percent of the vote in a low turnout primary. One-quarter of Pennsylvania’s 9 million registered voters cast ballots.

In Idaho, by contrast, Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin, who also claimed Joe Biden’s election was illegitimate and has campaigned at white supremacist rallies, according to the Western States Center, an Oregon-based group that monitors the far right, lost her bid for the GOP gubernatorial nomination to incumbent Gov. Brad Little.

Idaho also saw two 2020 election-denying candidates vying for the GOP nomination for secretary of state lose to a career civil servant and election administrator who defended 2020’s results as accurate. On the other hand, an ex-congressman who is an election denier won the GOP primary for attorney general.

“In addition to Janice McGeachin, who was defeated in her bid for governor, a number of other anti-democracy candidates were rejected by voters, including Priscilla Giddings, who ran for [Idaho] Lieutenant Governor; Dorothy Moon, who ran for Secretary of State; and Chad Christensen, Todd Engel and Eric Parker, who mounted bids for the state legislature,” the Western States Center’s analysis said. “In Ada County, antisemitic sheriff candidate Doug Traubel was soundly defeated, alongside losses for Proud Boy and conspiratorial candidates in Oregon.”

Voters in Western states with histories of far-right organizing and militia violence have more experience sizing up extremist politics and candidates than voters out East, the center suggested. However, as May 17’s five state primaries make clear, the GOP’s far-right flank is ascendant nationally.

Various stripes of GOP conspiracy theorists and uncompromising culture war-embracing candidates attracted a third or more of the May 17 primary electorate, a volume of votes sufficient to win some high-stakes races in crowded fields.

Low Turnouts Boost GOP Radicals

The highest-profile contests were in the presidential swing state of Pennsylvania, where Mastriano, a state legislator, won the gubernatorial primary with votes from less than 7 percent of Pennsylvania’s 9 million registered voters.

In its primary for an open U.S. Senate seat, several thousand votes separated two election-denier candidates, a margin that will trigger a recount. As Pennsylvania’s mailed-out ballots are counted and added into totals, the lead keeps shifting between hedge-fund billionaire David McCormick and celebrity broadcaster Dr. Mehmet Oz.

Mastriano campaigned on his rejection of President Joe Biden’s victory, chartered buses to transport Trump supporters to the U.S. Capitol for what became the January 6 insurrection, is stridently anti-abortion and often says his religion shapes his politics. On his primary victory night, he sounded like former President Trump, proclaiming that he and his base were aggrieved underdogs.

“We’re under siege now,” Mastriano told supporters, according to a Philadelphia Inquirer report. “The media doesn’t like groups of us who believe certain things.”

That “siege” appears to include a cold shoulder from pro-corporate Republicans who campaigned against Mastriano as the primary crested, fearing that he would lose in the fall’s general election. A day after the May 17 primary, the Republican Governors Association downplayed his victory, a signal that it was unlikely to steer donors toward him, the Washington Post reported.

Other election-denying candidates sailed to victory across Pennsylvania, including five GOP congressmen who voted against certifying their state’s 2020 Electoral College slate: Scott Perry, John Joyce, Mike Kelly, Guy Reschenthaler and Lloyd Smucker. Their primaries, while not garnering national attention, underscore Trump’s enduring impact on wide swaths of the Republican Party.

It remains to be seen if any of the primary winners will prevail in the fall’s general election. It may be that candidates who can win in crowded primary fields when a quarter to a third of voters turn out will not win in the fall, when turnout is likely to double. But a closer look at some primary results shows that large numbers of Republican voters are embracing extremists—even if individual candidates lose.

That trend can be seen in Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor’s race. The combined votes of three election-denying candidates (Rick Saccone, 15.69 percent; Teddy Daniels, 12.18 percent; Russ Diamond, 5.93 percent) was about 34 percent. That share of the party’s electorate, had it voted for one candidate, would have defeated the primary winner, Carrie DelRosso, a more moderate Republican who received 25.65 percent of the vote and will have to defend conspiracies as Mastriano’s running mate.

Fissures Inside the GOP

While Trump-appeasing candidates won primaries in May 17’s four other primary states—Idaho, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Oregon—some outspoken and badly behaved GOP radicals, such as North Carolina’s Rep. Madison Cawthorn, lost to a more traditional conservative Republican.

Cawthorn was defeated by Chuck Edwards, a pro-business Republican and state senator described by the Washington Post as “a McDonald’s franchise owner [who] was head of the local chamber of commerce.”

Edwards campaigned on returning the House to a GOP majority and backed a predictable obstructionist agenda to block the Biden White House, as opposed to Cawthorn’s embrace of 2020 election conspiracies and incendiary antics—which included taking loaded guns on planes and accusing other GOP congressmen of lurid and illegal behavior.

Edwards’ focus, the Washington Post reported, “will be on ‘removing the gavel out of Nancy Pelosi’s hand, and then taking the teleprompter from Joe Biden and restoring the policies that we enjoyed under the Trump administration, to help get this country back on track.’”

Cawthorn’s defeat came as North Carolina Republicans chose a Trump-praising candidate, Ted Budd, for its U.S. Senate nomination over an ex-governor, Pat McCrory.

As Tim Miller noted in the May 18 morning newsletter from the Bulwark, a pro-Republican but anti-Trump news and opinion website, McCrory had “criticized Trump over his Putinphilia and insurrectionist incitement… he lost bigly to Ted Budd, a milquetoast Trump stooge who will do what he’s told.”

As in Pennsylvania, a handful of incumbent members of congress in North Carolina who voted to reject their 2020 Electoral College slate easily won their primaries.

“Virginia Foxx and Greg Murphy voted to overturn the results of the 2020 election after the events of January 6 and have been endorsed by Trump in their 2022 campaigns,” said a May 16 fact sheet from the Defend Democracy Project, which tracks the GOP’s election-denying candidates. “Foxx was later fined $5,000 for failing to comply with security measures put in place in the House after the January 6 attack and Murphy has claimed that antifa may have been responsible for the violence at the Capitol.”

Foxx won her primary with 77 percent of the vote. Murphy won his primary with 76 percent of the vote.

Idaho Republicans Clash

The election-denial and conspiracy-embracing candidates fared less well in May 17’s primaries out West, the Western States Center’s analysis noted.

“Yesterday in elections in Oregon and Idaho, anti-democracy candidates were defeated in several marquee races,” it said on May 18. “Most notably Idaho gubernatorial hopeful Janice McGeachin, whose embrace of white nationalism and militias was soundly rejected by voters.”

In the GOP primary for secretary of state, which oversees Idaho’s elections, Ada County Clerk Phil McGrane narrowly beat two 2020 election deniers, state Rep. Dorothy Moon (R-Stanley) and state Sen. Mary Souza (R-Coeur d’Alene). McGrane had 43.1 percent or 114,348 votes. Moon had 41.4 percent, or 109,898 votes. Souza had 15.5 percent or 41,201 votes.

“Donald Trump carried Idaho by 30 points in 2020, but… State Rep. Dorothy Moon has alleged without evidence that people are ‘coming over and voting’ in Idaho from Canada and called for the decertification of the 2020 election,” said the Defend Democracy Project’s fact sheet. “State Sen. Mary Souza is part of the voter suppression group the Honest Elections Project and has blamed ‘ballot harvesting’ for Biden’s victory. Only Ada County Clerk Phil McGrane has stated that he believes that Idaho’s elections are legitimate and that Joe Biden was the winner of the 2020 election.”

Another way of looking at the contest’s results is that an election-denying candidate might have won, had Idaho’s Republican Party more forcefully controlled how many candidates were running for this office. Together, Moon and Souza won nearly 57 percent of the vote, compared to McGrane’s 43 percent.

McGrane will be part of a GOP ticket that includes an election denier who won the primary for attorney general. Former congressman Raul Labrador received 51.5 percent of the vote, compared to the five-term incumbent, Lawrence Wasden, who received 37.9 percent. Labrador accused Wasden of “being insufficiently committed to overturning the 2020 election,” the Defend Democracy Project said.

On the other hand, another 2020 election defender won his GOP primary. Rep. Mike Simpson won 54.6 percent of the vote in Idaho’s 2nd U.S. House district in a field with several challengers who attacked him for being one of 35 House Republicans who voted in favor of creating the January 6 committee.

What Do GOP Voters Want?

But Mastriano’s victory in Pennsylvania’s GOP gubernatorial primary, more so than any other outcome from May 17’s primaries, is “giving the GOP fits,” as Blake Hounshell, the New York Times’ “On Politics” editor, wrote on May 18.

“Conversations with Republican strategists, donors and lobbyists in and outside of Pennsylvania in recent days reveal a party seething with anxiety, dissension and score-settling over Mastriano’s nomination,” Hounshell said.

That assessment may be accurate. But one key voice—or GOP sector—is missing from the New York Times’ analysis: the GOP primary voters, a third or more of them on May 17, who embraced conspiratorial candidates—though more widely in the East than in the West.

For decades we’ve seen that our [Western] region has been a bellwether for white nationalist and paramilitary attacks on democratic institutions and communities, but also home to the broad, moral coalitions that have risen up to defeat them,” said Eric K. Ward, the Western States Center’s executive director. “The defeat of anti-democracy candidates with white nationalist and paramilitary ties up and down the ballot is evidence that those of us committed to inclusive democracy, even if we have vastly different political views, do indeed have the power to come together to defeat movements that traffic in bigotry, white nationalism and political violence.”

Steven Rosenfeld

Independent Media Institute

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.