Archive for category: Uncategorized

Asking himself how deep the reconstruction of the project of Enlightenment has to go, McCarraher’s answer is an emphatically italicized “all the way down” I think he’s right.

Ishan Desai-Geller

The post When Did the Ruling Class Get Woke? appeared first on The Nation.

The Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey set the attitude of the mainstream view on the impact of inflation in February, when he said that “I’m not saying nobody gets a pay rise, don’t get me wrong. But what I am saying is, we do need to see restraint in pay bargaining, otherwise it will get out of control”.

Bailey followed the Keynesian explanation of rising inflation as being the result of a tight (‘full employment’) labour market allowing workers to push for higher wages and thus forcing employers to hike prices to sustain profits. This ‘wage-push’ theory of inflation has been refuted both theoretically and empirically, as I have shown in several previous posts.

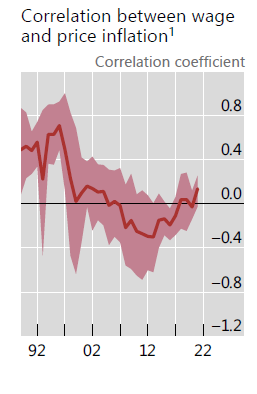

And more recently the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) study confirms that “by some measures, the current environment does not look conducive to such a spiral. After all, the correlation between wage growth and inflation has declined over recent decades and is currently near historical lows.”

But this wage push theory persists among orthodox Keynesians because they think full employment breeds inflation; and it is supported by the authorities because it ignores any impact on prices by businesses attempting to boost profit. Bailey did not talk about ‘restraint’ in market pricing or profits.

The wage-push theory existed before Keynes. As far back as in the mid-19th century, the neo-Ricardian trade unionist Thomas Weston argued in the circles of the International Working Man’s Association that workers could not push for wages that were higher than the cost of subsistence because it would only lead to employers hiking prices and was therefore self-defeating. For Weston, there was an ‘iron law’ of real wages tied to the labour time required for subsistence which could not be broken.

Marx rebutted Weston’s views both theoretically and empirically in a series of speeches published in the pamphlet, Value Price and Profit. Marx argued that the value (price) of commodity ultimately depended on the average labour time taken to produce it. But that meant the shares of that labour time between the workers who created the commodity and the capitalist who owned it was not fixed but depended on the class struggle between employers and employed. As he said, “capitalists cannot raise or lower wages merely at their whim, nor can they raise prices at will in order to make up for lost profits resulting from an increase in wages.” If wages are ‘restrained’ that may not lower prices but instead simply increase profits.

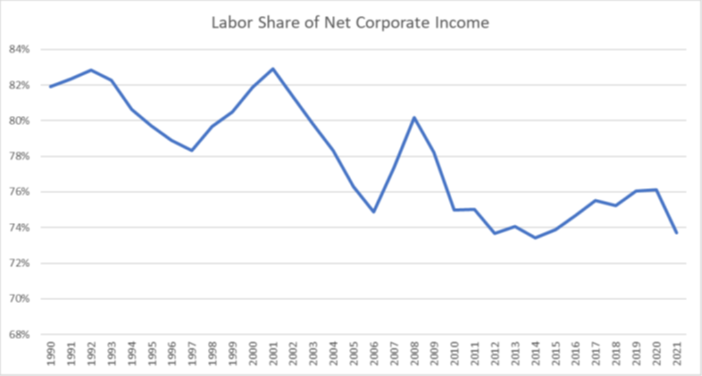

Indeed, that is what is happening now in the current bout of inflation. In the Great Recession recovery, price growth was actually quite subdued over the first few years of that recovery. Corporations instead applied extreme wage suppression (aided by high and persistent levels of unemployment). Unit labour costs (ie the cost of labour per unit of production) fell over a three-year stretch from the recession’s trough in the second quarter of 2009 to the middle of 2012.

There has been a general pattern of the labour share of income falling during the early phase of recoveries characterized most of the post–World War II recoveries, though it has become more extreme in recent business cycles. By 2019, labour’s share was at all-time low. The decade of the 2010s saw basically a stagnation of average real wages in most major economies.

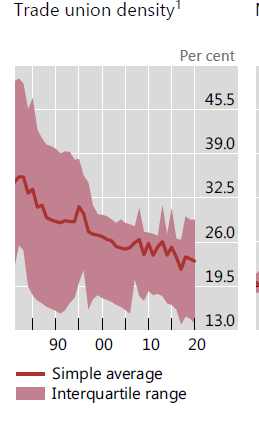

In a recent report, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) makes the point that “in recent decades, workers’ collective bargaining power has declined alongside falling trade union membership. Relatedly, the indexation and COLA clauses that fuelled past wage-price spirals are less prevalent. In the euro area, the share of private sector employees whose contracts involve a formal role for inflation in wage-setting fell from 24% in 2008 to 16% in 2021. COLA coverage in the United States hovered around 25% in the 1960s and rose to about 60% during the inflationary episode of the late 1970s and early 1980s, but rapidly declined to 20% by the mid-1990s “

Since the COVID slump, labour’s share of income and real wages have been falling sharply even as unemployment falls. This is the complete opposite of the Keynesian inflation theory and the so-called ‘iron law of wages’ proposed by Weston against Marx. The rise in inflation has not been driven by anything that looks like an overheating labour market—instead it has been driven by higher corporate profit margins and supply-chain bottlenecks. That means that central banks hiking interest rates to ‘cool down’ labour markets and reduce wage rises will have little effect on inflation and are more likely to cause stagnation in investment and consumption, thus provoking a slump.

Prices of commodities can be broken down into the three main components: labour costs (v= the value of labour power in Marxist terminology, non-labour inputs (c =the constant capital consumed, and the “mark-up” of profits over the first two components (s = surplus value appropriated by the capitalist owners). P = v + c + s.

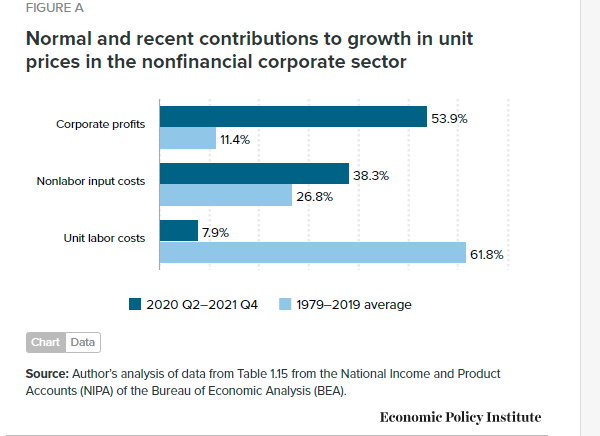

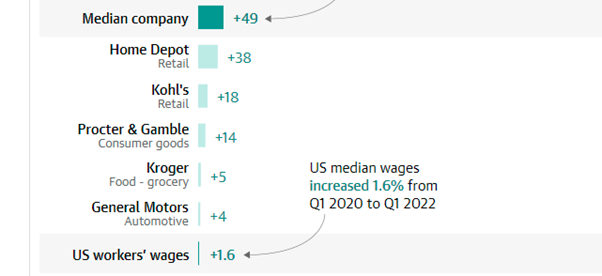

The Economic Policy Institute reckons that, since the trough of the COVID-19 recession in the second quarter of 2020, overall prices in the producing sector of the US economy have risen at an annualised rate of 6.1%—a pronounced acceleration over the 1.8% price growth that characterized the pre-pandemic business cycle of 2007–2019. Over half of this increase (53.9%) can be attributed to fatter profit margins, with labour costs contributing less than 8% of this increase. This is not normal. From 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 11% to price growth and labour costs over 60%. Non labour inputs (raw materials and components) are also driving up prices more than usual in the current economic recovery.

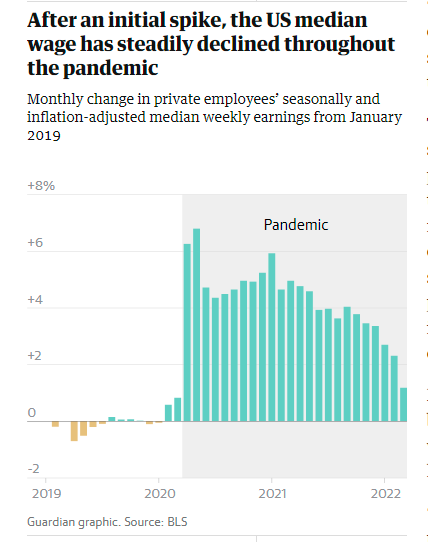

Current inflation is concentrated in the goods sector (particularly durable goods), driven by a collapse of supply chains in durable goods (with rolling port shutdowns around the world). The bottleneck is not labour asking for higher wages, shipping capacity and other non-labour shortages. Indeed, in the current inflation spike, US weekly earnings growth has been slowing month by month.

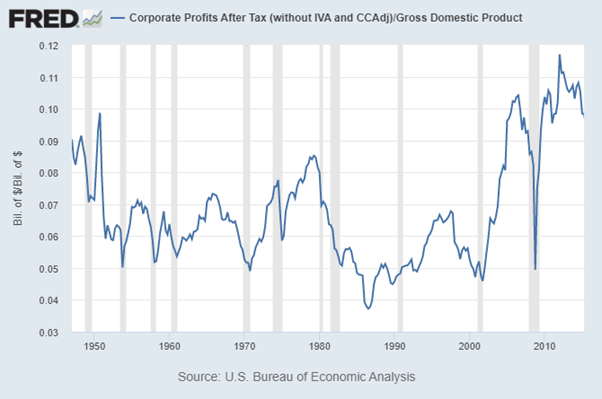

It’s profits that have been spiralling upwards. Firms that did happen to have supply on hand as the pandemic-driven demand surge hit have had enormous pricing power vis-à-vis their customers. Corporate profit margins (the share going to profits per unit of production) are at their highest since 1950.

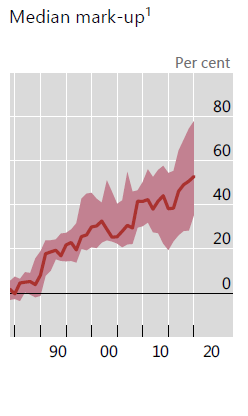

The BIS study finds similarly: “Firms’ pricing power, as measured by the markup of prices over costs, has increased to historical highs. In the low and stable inflation environment of the pre-pandemic era, higher markups lowered wage-price pass-through. But in a high inflation environment, higher markups could fuel inflation as businesses pay more attention to aggregate price growth and incorporate it into their pricing decisions. Indeed, this could be one reason why inflationary pressures have broadened recently in sectors that were not directly hit by bottlenecks.”

An analysis of the Securities and Exchange Commission filings for 100 US corporations found net profits up by a median of 49% in the last two years and in one case by as much as 111,000%!

Chief executives are acutely aware to the ability to hike prices in this inflationary spiral. Hershey bar CEO Michel Buck told shareholders: “Pricing will be an important lever for us this year and is expected to drive most of our growth.” Similarly, a Kroger executive told investors “a little bit of inflation is always good for our business”, while Hostess’s CEO in March said rising prices across the economy “helps” profits.

Does this mean that companies can raise prices at will and are engaged in what is called ‘price-gouging’? Marx, arguing with Weston in 1865, did not think that was the case in general. The power of competition still ruled. George Pearkes, an analyst at Bespoke Investment, pointed to Caterpillar, which recorded a 958% profit increase driven by volume growth and price realization between 2019 and 2021’s fourth quarters. Eliminating price increases may have dropped the company’s 2021 quarter four operating profits slightly below the $1.3bn it made in 2020. “This isn’t price gouging … and it shows pretty concretely that there’s a lot of nuance here,” Pearkes said, adding profiteering is “not the primary driver of inflation, nor the primary driver of corporate profits”. Indeed, companies that push prices as hard as the current environment allows to maximise profits in the short run may find themselves paying a price in market share down the road as others get into the game. It is clear, however, that the concentration of capital is any sector, the greater ability to hike prices. “When you go from 15 to 10 companies, not much changes,” one analyst argued. “When you go from 10 to six, a lot changes. But when you go from six to four – it’s a fix.”

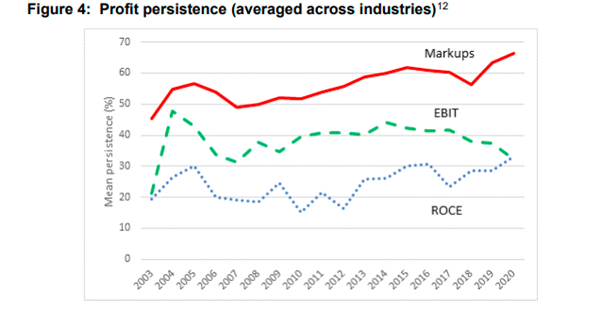

Recently, the UK’s Competitions and Market Authority (CMA) published an important report. The CMA found a mixed picture.Profit persistence has increased as measured by markups over marginal costs and the return on capital but not when measured by profits before tax.

And the CMA also found that the more international competition there was, the less ability for firms to increase prices and mark-ups. “This highlights the important role that international trade plays in contributing to keeping UK markets competitive.” The BIS summed up this debate: “In product markets, the degree of competition comes into play. Firms with higher markups – an indication of greater market power – could raise prices when wages increase, while those without such pricing power may hesitate to do so. Strategic considerations in price-setting are also relevant. Firms may feel more comfortable raising prices if they believe their competitors will also do so. Price increases are more likely when demand is strong. With less concern about losing sales and less room to adjust profit margins, even firms with less pricing power could pass higher costs through to customers.”

As a partner in the Bain consultancy, an adviser to many corporations, argued, “when times are tough, screw your customers while the screwing is good!”. The consultant went on: “I don’t think this is actually nefarious at all. Companies should charge what they can. Profit is the point of the whole exercise.”

This year is on track for record lobbying spending after lobbyists collectively clocked the biggest first quarter haul in history — with more than $1 billion disclosed during the first quarter of 2022 alone.

At this point in 2021, 10,503 lobbyists had brought in less than $929 million across all industries.

The federal budget was the most lobbied issue from January through March, with 3,394 clients paying for lobbying on the issue. Health issues were also heavily lobbied, with 2,068 clients.

Lobbying related to health continues to dominate spending as recovery from the coronavirus pandemic continues.

The health sector accounted for about $187 million in this year’s first quarter and $689 million over the course of 2021. Of the 3,130 lobbyists working for the health sector last year, nearly half — 47.8% — had taken a swing in the revolving door as former government employees.

Within the sector, the pharmaceuticals and health products industry continues to be a top lobbying spender as various companies fight drug pricing regulations, grapple with supply chain issues and seek approval for vaccinations.

Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America ranked third overall in the first quarter of 2022 with nearly $8.3 million in spending during that period. The pharmaceuticals industry trade group was the third largest lobbying spender of 2021 at over $30 million for that full year.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield is the fourth highest lobbying spender overall with about $7.6 million in the first quarter of 2022. The health insurance company spent over $25 million on lobbying last year, making it the fifth biggest lobbying spender overall in 2021.

The American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association are also major lobbying spenders with about $6.6 million in spending from each during the first quarter of 2022. The associations were also neck and neck in 2021 with their national associations spending about $20 million each on lobbying over the year, putting them among the top spenders. Along with its state affiliates, the American Hospital Association’s federal lobbying spending topped $25 million in 2021.

America’s Health Insurance Plans spent another $4.7 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, more than any prior quarter in the health insurance industry trade group’s history.

Biotechnology Innovation Organization spent nearly $3.2 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, falling lower among the ranks of lobbying spending but remaining a powerful influencer for the biotechnology industry.

Lobbying Stalwarts Continue to Top Spending Charts

While the health industry dominates overall, the top spender of this year’s first quarter was the U.S. Chamber of Commerce with about $19 million in lobbying spending.

A longtime top lobbying spender with more than $1.7 billion spent since 1998, the Chamber spent over $66 million on lobbying in 2021 alone. The business lobbying group’s heavy spending made it the top lobbying spender of 2021 despite fallout among Republicans after the Chamber’s endorsement of 30 Democrats seeking House seats in 2020, which led to several key officials parting ways with the group and criticism from GOP lawmakers.

The Chamber is also a big spender on elections, spending millions on ads targeting politicians it may later lobby. During the 2020 election cycle, the Chamber’s spending on electioneering communications – which can boost and attack candidates without explicitly advocating for their election or defeat – topped $5.7 million.

The National Association of Realtors was the second highest lobbying spender with over $12 million in the first quarter of this year.

The Realtors association was also the second highest spender in 2021 as it faced further scrutiny from the Justice Department related to antitrust issues, pouring about $40 million into lobbying spending over the course of last year. The association’s 2020 lobbying spending topped $84 million, the largest amount the association has spent on lobbying in any single year, and more than any other organization spent on lobbying that year.

While the association’s lobbying spending dipped in 2021, it has a history of dropping in non-election years. The association’s $12 million in first quarter spending is over $4 million more than it spent on lobbying during the same period last year but still about $1.5 million less than it spent during the first quarter in 2020.

Like the Chamber, the National Association of Realtors also spends to influence U.S. elections directly, along with its affiliated political groups, pouring more than $20 million into 2020 spending.

Technology companies were also among the top 10 lobbying spenders of 2022’s first quarter.

Facebook’s parent company, Meta, spent nearly $5.4 million on lobbying while online retail giant Amazon spent over $5.3 million.

With an eye to this November’s

elections, Paul Spink—like many union leaders in Wisconsin—plans to do his utmost this year to salvage what’s left of

democracy in his state. Spink, president of

the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, in

Wisconsin, says it’s vital to reelect the state’s Democratic governor, Tony

Evers, to preserve some semblance of majority rule in Wisconsin and to keep

some check on what he sees as a runaway Republican legislature that is pushing

hard to lock in GOP rule for the next 10 years.

“It’s really hard to use the term ‘democracy’ to describe what’s happening now in Wisconsin,” Spink said. “It has

been years of them trying to undermine the idea of having average people pick

their leaders.”

In 2010, a year when the GOP made major gains in state races across

the nation, Republicans won control of Wisconsin’s governor’s mansion and both

houses of its legislature. The next year, Republicans approved a gerrymandered district map that ensured continuation of the

GOP majority in both legislative houses in election after election, even when

Democrats won a majority of votes statewide in legislative races. Spink

complains that Wisconsin’s Republicans are now parlaying that decade-old

gerrymander into a more egregious one aimed to lock in a veto-proof majority.

Spink is outraged that Wisconsin’s

Republican legislature—aided by a ruling from the United States Supreme Court’s hard-right

majority—pushed through a redistricting plan that aims to give the GOP veto-proof,

two-thirds control of

the State Assembly and Senate even though

the Democrats won all five top races for statewide office in 2018. Spink said that if the Republicans win either the governorship or a veto-proof legislative majority in November,

“we’ll see them passing more and more laws to make it so they’ll never lose

power.”

Noting Wisconsin’s progressive,

labor-friendly past—it was the first state to enact

unemployment insurance, for example—Spink

added, “We used to be a laboratory of democracy. Now we’ve become a laboratory

of autocracy.”

Spink, a 43-year-old Milwaukee resident, became head of

AFSCME in Wisconsin in 2015, after years working as a state employee who

inspected childcare centers for safety. Spink typically talks with a calm

demeanor, but when he turns to the precarious state of democracy in Wisconsin,

frustration and anger quickly seep into his voice.

“In recent months,

there’ve been at least five or six bills the

legislature passed to limit voting rights and undermine

elections,” Spink said. “We’re trying very hard to keep a Democratic governor

in this state to block those.”

When John Johnson, a Marquette

University law professor, analyzed the GOP’s voting map this April, he

predicted hugely skewed results for this November: that Republicans would win 63 out of Wisconsin’s 99 Assembly

seats and 23 out of 33 Senate seats—this in a state with a population that is

widely viewed as being split 50–50 between Democrats and Republicans. Gerrymandering of

this magnitude is unhealthy in a democracy; not only does it disadvantage

certain blocs of voters over others, diluting the power of their votes, it also

undermines the validity of the resulting government itself. Spink very much hopes that organized labor and its allies

will—by helping Democrats win enough of the

few legislative districts that remain competitive—manage to block the GOP’s ambitions to secure a veto-proof

majority in both houses.

Spink aims to mobilize hundreds of AFSCME

members to knock on doors, do phone-banking, and speak to fellow employees in

the workplace to explain that democracy is on the line and that Republican

politicians, from Donald Trump on down, have delivered far more to corporations

and the wealthy than to the nation’s workers. “It’s up to me and people like me

to beat the odds in some of these districts,” Spink said. “We’re going to have

to run a better political program than we have before. It will be all hands on

deck.”

Making Spink’s political efforts

tougher, back in 2011 Wisconsin’s then-Governor Scott Walker and the

Republican-led legislature enacted a landmark anti-union law that aimed to

cripple most of the state’s government employee unions by creating several

hurdles that made it harder and more expensive for union locals to survive.

(One of those hurdles is a hard-to-win annual recertification vote with rules

stacked hugely against unions.) As a result of that law, AFSCME’s Wisconsin

membership has plummeted to just 10,000 from over 50,000 a decade ago. Indeed,

largely as a result of that 2011 law and other measures to weaken unions,

Wisconsin’s union membership has plunged by 170,000, or 44 percent, since 2009, with the percentage of workers in unions falling to 7.9 percent from 15.2

percent—the steepest drop of any state. Wisconsin’s Republicans recognized that by weakening

labor unions and their treasuries, they would undermine the Democrats’

electoral chances.

Spink said, “We’ll just have to

punch above our weight when it comes to the total number of doors we’re going

to hit and the calls we’re going to make and some of the checks we’re going to

write.”

The GOP push to undermine majority rule by minimizing the

political voice of unions and minority voters will hurt Wisconsin’s workers,

Spink says. He predicts

that veto-proof Republican control will mean new legislation to increase child

labor and little effort to modernize the state’s balky unemployment insurance

system. Wisconsin Republicans have proposed letting 14-year-olds work until 9:30 p.m. on school days and until 11:00 p.m. on non-school days.

“If we don’t have democracy,” Spink

said, “there is no fairness for working people.”

The need for a nationwide effort

Across the nation, many labor leaders share Spink’s alarm

about preserving democracy as well as his goal of punching above one’s weight

in this year’s elections. They view this year’s election and 2024’s with dire urgency, as

a goal-line stand to defend America’s democracy;

and they also understand that, thanks to

organized labor’s ability to mobilize tens of thousands of foot soldiers,

America’s unions, with their 14 million members, are one of the nation’s most

potent and effective political forces.

Labor unions typically focus on

presidential and congressional races, but this year, in Wisconsin and

elsewhere, they plan to focus far more than usual on state and local races—for instance, to defeat Republican

candidates for elections commissions and secretaries of state who support

Trump’s “Big Lie” and who have suggested they will overturn their state’s vote

results in 2024 if the Democratic presidential nominee comes out ahead.

Political scientists say unions can

play a big role in preventing Trump and other Republicans from subverting

America’s democracy. “Unions are a huge mobilizer,” said Paul Frymer, a

political science professor at Princeton. “They’re one of the biggest

mobilizers for the Democratic Party, maybe the biggest.”

Shane Larson, director of government affairs for the

Communications Workers of America, sees a big attitude shift among union

leaders—to far greater

urgency. Larson said that many labor leaders, as usual, wanted to focus

overwhelmingly on jobs and other economic matters and weren’t paying much heed

to warnings that America’s democracy was threatened. January 6, 2021, was a huge “wake-up call” to those union leaders,

Larson said.

Now, he said, “the conversation among union presidents is

that our movement has to do something here for our democracy or we can lose

it.” Larson added

that part of labor’s focus this year “is to hold accountable a number of insurrectionists running for some of

these offices.”

Randi Weingarten,

president of the American Federation of Teachers, said some union leaders,

along with many Americans, “still

don’t have the imagination to believe that this [the destruction of democracy]

could happen in America. There’s a sense that our democracy is so well rooted

that nothing will dislodge it. If there is one thing that I could help change

right now, it is for people to have the sense of imagination that it could

happen here. Once you lose a certain number of democratic institutions, it’s

very hard to get them back.”

Ensuring broader participation

America’s labor unions are pursuing

two interlocking strategies in their effort to protect and preserve America’s

democracy. One strategy is to battle against efforts that would reduce the

voice of minority voters, make it harder to vote, and empower Trump partisans

to twist and even overturn vote counts. The second strategy is to make sure

that Democrats win pivotal states, especially longtime union strongholds, such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and

Wisconsin, but also states that have more recently moved from red to blue, such

as Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Virginia.

“For me, protecting democracy right now means

rebuilding the blue wall in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania,” said Steve

Rosenthal, a former AFL-CIO political director. “Without those states, there is no

way that Donald Trump or the next Donald Trump or any anti-worker candidate

could win in 2024.”

In Rosenthal’s view,

if union households totaled 25 to 30 percent of the vote in those three

industrial states, as they did 25 years ago, instead of

totaling 15 or 20 percent, as they do today, Trump would never have won

Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in 2016—and with them the election. Nor would he be able to win those states again in 2024.

There are hundreds of thousands of former union members in those three states,

who are no longer contacted by their union, who no longer receive union

political literature, who no longer have union members knocking on their doors,

and that, many political experts say, helps explain why Trump was able to

narrowly win those three states in 2016. (Many unions were so confident that

Hillary Clinton would win those states that they didn’t mount nearly as much of

a campaign effort as they might have.)

For many labor leaders and

Democratic lawmakers, a major concern is that many blue-collar workers—union members, former union members, and

nonunion workers—have gotten swept into a

right-wing echo chamber that amplifies the messaging from Fox News, Sinclair Broadcasting, Breitbart, Mark Levin,

Charlie Kirk, Sean Hannity, and Tucker Carlson. “Where we’re failing is with

the right-wing sound machine and echo chamber—their

message is constantly reinforced,” Larson said. “We have to figure out, how are

we going to counter that story? The one thing we

know is that workers value their union as an information source. In a time when

people don’t trust information sources, we’re constantly finding they see their

unions as a valid source of information—even

if workers don’t agree all the time with their union.”

Rosenthal has founded

a group, In Union, that aims to

counter the right-wing echo chamber and give blue-collar workers accurate

information on what’s happening in the economy and what various candidates

stand for. His group keeps in regular contact with hundreds of thousands of

former union members in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Those voters

perhaps lost their union membership when their steel mills or auto plants

closed and they lost their jobs. In Union sends emails and texts, mails

newsletters, and knocks on doors to talk to voters about issues months in

advance of elections and then holds long conversations at voters’ doors closer

to the election about which candidates are pro-worker and which aren’t.

Throughout 2020, In Union was in regular contact with 1.2 million voters in

Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin (including many nonunion voters who

surveys show share the views of union members). Rosenthal hopes to get funding

to reach out to another three million nonunion voters in the coming months.

With money from

unions, foundations, and individuals, his group seeks to build trust with those

voters and explain, for example, as it did during the 2020 election, how Joe

Biden would do more for workers than Donald Trump would. A

recent In Union newsletter for Pennsylvania voters explains what new

infrastructure investments will mean for Pennsylvania and how Biden’s new rules

mandate that the federal government use its powers to buy American-made goods.

Jacob Grumbach, a political science professor at the

University of Washington, says unions can play an important role in offsetting

the GOP’s repeated use of cultural issues such as transgender rights and critical race theory to create “moral

panics” in order to get blue-collar workers to vote

Republican. “They often vote now based on anti-immigrant views and culture-war

issues,” Grumbach said, “but compare that becoming a priority to how people

voted when unions were the main organizing force for the working class.”

Grumbach said the Biden administration recognizes the

political advantages of strengthening unions. “Hopefully it’s not too little too late,” he said. “It’s

crucial for the Democrats to have this long-term base to structure politics

around material circumstances [such as housing

affordability and access to childcare] rather than around a cultural war.”

Many labor leaders say Democratic lawmakers have

unwittingly undermined their party’s chances by doing so little in recent

decades to stop unions’ membership and clout from declining. More than 20

percent of all workers were in unions in the 1980s, but that has fallen to just

10 percent today.

“For a long time, the Democrats have ignored just how

important unions are to represent workers and raise salaries—and how important they are to the

Democratic Party for winning elections,” said Princeton’s Frymer. “They let the union decline happen right before their eyes.

They didn’t do anything to stop it. They let their coalition decline.”

Over the past 50 years, the Democrats have repeatedly failed to enact

legislation to make it easier for unions to grow. Democratic lawmakers are

quick to note that Republican filibusters blocked efforts by Presidents Carter,

Clinton, Obama, and Biden to make it easier to unionize.

While labor leaders often criticize Carter,

Clinton, and Obama for not doing enough to strengthen unions, they give higher

praise to Joe Biden. Biden and his administration seem eager to reverse the

decline in union membership and union power, all while many Republicans are

clearly intent on hastening labor’s decline. Biden has vigorously backed the

Protecting the Right Organize, or PRO, Act, one of the most comprehensive

pieces of pro-union legislation since the New Deal. But that legislation, which

the House has approved, has stalled in the Senate, not just because of a

Republican filibuster but because several Democratic senators have opposed it,

undermining efforts to get even a simple majority of senators to back it.

It is well known that unions boost election prospects for Democratic candidates by

educating union members on issues and getting out the vote through door knocking

and phone banking. But unions help the Democrats in other important ways.

Various academic studies have found that unions help discourage workers from

backing right-wing populists such as Trump who

appeal to worker resentment. Unions help prevent workers from growing resentful

and alienated by delivering economic gains, by rooting workers in social

networks, and by reducing racial resentment among white workers. Unionized workers are more prosperous than nonunion

workers in comparable jobs. They earn more; receive better health coverage and

pensions; and have more job security, vacation days, and paid sick days.

A study of union

members by Frymer and Grumbach found that by bringing

workers of different races together and having them cooperate in pursuit of

common goals, unions reduce racial resentment. “White

union members,” they write, “have lower racial resentment and greater support

for policies that benefit African Americans.” As a candidate, Trump milked many

white workers’ racial resentment to win their support.

Unions have long played a big role reaching that

much-analyzed, much-discussed demographic: blue-collar whites. That group was

key to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition but has moved sharply away from

the Democrats in recent years. Unions have tempered that shift, however. Frymer

and Grumbach found that white union members vote eight to 14 percentage points more for Democrats than do white nonunion members. This

more Democratic

tilt among white union members accounted for 1.7 percentage points of Obama’s victory margin in 2008 and again in 2012, several studies have found.

“Unions remain the

only set of organizations in the U.S. that can help prevent working-class

whites from going conservative,” said Jake Rosenfeld, a sociology professor at

Washington University in St. Louis. While Trump often boasts that he did

well among union members, Rosenfeld reminds us that Trump lost among union

members in both 2016 and 2020.

It is often forgotten

that unions frequently

educate and engage typical Americans in the basics of

democracy and civic activism. In that way, unions help to get many

nonaffluent Americans involved in politics, and that, at least somewhat,

offsets the disproportionate political voice that corporations and the wealthy

have thanks to their lobbying and hefty campaign donations. Robert D.

Putnam, author of Bowling Alone, has

praised unions for building an important sense of community—with their meetings, marches, protests, and

picnics—and for serving as “schools for

democracy,” where workers get involved in everything from collective bargaining

to debates in union meetings to canvassing in political campaigns.

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, a political science professor

at Columbia University who is overseeing some research for the Labor Department, said, “Unions serve as a school for democracy for citizens by

introducing individuals, particularly those who might not be involved in other

civic organizations, to the rhythms of democracy.”

The ground game

When it comes to

fighting to defend democracy, Unite Here, a 300,000-member union of hotel and

restaurant workers, has perhaps punched above its weight more than any other

union. It was a principal sponsor of a modern-day “Freedom

Ride,” in which 1,500 hotel housekeepers, dishwashers, and other

union members were bused into Washington along with Black Lives Matters

activists and other allies to press Congress to enact new voting rights

protections. In Arizona, Unite Here co-sponsored a hunger

strike to pressure Senator Kyrsten Sinema to enact voting rights legislation.

The union also posted videos and ran full-page newspaper ads to press Arizona’s

Republican legislature not to roll back voting rights, and it pushed Arizona

lawmakers to condemn Cyber Ninjas’ much-derided review of the presidential

vote.

Other unions have

also done their best to dissuade GOP-led state legislatures from making it

harder for people to vote, but that’s an uphill battle in deep-red states where

many lawmakers have swallowed Trump’s lie about widespread voter fraud. In

Georgia and Texas, the Service

Employees International Union ran internet ads that criticized Coca-Cola, Delta

Airlines, Home Depot, and other corporations for donating to lawmakers who

backed new voting restrictions. AFSCME, the National Education Association, and the American

Federation of Teachers held rallies in Washington, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and

Detroit to defend the right to vote

and protest efforts to make it harder for Americans of color to vote. AFSCME also provided plaintiffs in lawsuits

that have challenged new laws that it says

illegally discriminate against and disenfranchise voters of color. Many unions are urging their members to serve as poll

watchers in communities where they fear that Trumpist poll watchers will seek

to intimidate voters of color.

At the same time, AFSCME and other unions are educating people about how to make

sure they can vote despite all the newly enacted voter restrictions, such as

laws cutting back on early voting, drop boxes, and Election Day registration.

“We’re not going to sit back and assume the courts are

going to help us out,” said Brian Weeks, AFSCME’s national political director. “We assume that we will

have problems, and we’ll make sure that our program helps overcome that.”

In recent months, teachers unions have fought a different

type of battle to defend democracy—often by fighting against book bans and defending teachers who face punishment for teaching about

racism. “In many countries, labor

unions have been a bulwark against authoritarianism,” said Weingarten of the

American Federation of Teachers.

Weingarten said her

union might endorse some non-Trumpist Republicans, such as Lynn Cheney, who

reject the “Big Lie” and Trump’s efforts to overturn election results. This

means that in districts where Democrats have little chance of victory, the

teachers union might help elect Republicans who oppose the GOP’s increasing embrace

of authoritarianism.

For the 2020 elections, Unite Here ran a huge

door-knocking operation that some political experts say could serve as a model

for the overall labor movement.

That

union had 500 full-time canvassers going door to door in Nevada and another 500

doing the same in Arizona. Unite Here says its canvassers contacted 48,364 infrequent voters in

Arizona who did not vote in 2016 and

urged them to back Biden. The union says that helps explain why Biden won

Arizona by 10,457 votes, a victory that surprised and shocked the Trump forces.

Many of Unite Here’s canvassers were hotel workers who were laid off during the

pandemic, and their union, often helped by funds from other unions, paid them

about $700 a week to canvas.

All told, Unite Here says its canvassers knocked on three million doors in Arizona, Florida, Nevada, and Pennsylvania in 2020 and talked

with more than 460,000 infrequent voters. Its canvassers did so well in those

states that Stacey Abrams asked Unite Here to send its canvassers to help push

Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff over the top in the Senate runoff in Georgia. The union says it sent 1,000 canvassers to

Georgia from Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and other states.

Chris Smith, a

53-year-old Unite Here member who works as a bartender in San Diego, spent six

weeks canvassing in Georgia. “People whose doors I knocked on, they

got excited,” Smith said. “They asked me a lot of questions. I felt I was

making a difference, that I did matter. We were going to turn the Senate away

from the bullying Republicans.”

Susan Minato,

co-president of Unite Here’s giant union local in Southern California and

Arizona, sees her union’s effort as an example for all of labor. “I want other

unions to have more people canvassing in these races, to do it in every state,”

she said. “That would be huge.”

Gwen Mills, Unite

Here’s secretary-treasurer, said the union’s goal is to have 1,500 union

members canvassing in key races this year, “going door to door, reigniting people to vote.” Mills said, “We try to keep a drum beat year

in and year out: Do democracy at work, do democracy at the doors, do democracy

at the polls, do democracy in the capital.”

With Stacey Abrams

running for governor in Georgia, Unite Here expects her to ask it to send in

some canvassers again this year. The

New Georgia Project is an influential voter registration and mobilization

organization founded by Abrams, and Eric Robertson, its labor liaison, said,

“Labor can have an outsized impact by being out there this year. They have

relationships with workers who are part of these communities. If the unions are

able to activate them, that’s going to move the dial, and moving the dial

is important in this election because the margins of victory will be so narrow.

Labor can really make a difference.”

This essay was commissioned by and is co-published with the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

News / 6th May 2022

The number of people suffering from extreme hunger reached an all-time high in 2021 and is on track to increase further this year—unless wealthy countries ramp up efforts to “tackle the root causes of food crises rather than just responding after they occur.