Archive for category: Uncategorized

Beijing will boost economy and introduce market-friendly policies, says top economic official Liu He

The state of Sunrise Movement, one of the more successful and visible U.S. Left organizations to emerge in the last five years, reflects trends in the broader Left. We hit a high-water mark with Sen. Bernie Sanders’ February 2020 victory in the Nevada caucus. Shortly after, the revenge of the Democratic establishment and the COVID pandemic halted all momentum and put Sunrise into a rear-guard…

The anti-psychiatry movement advanced a radical critique of the role that capitalism and power play in the medical profession. Its motives were noble, but it ended up closing the door to understanding, and properly treating, psychological suffering.

Leftists have understandably sought to find explanations of mental illness in the quotidian miseries of capitalist societies. (JEFF PACHOUD/AFP via Getty Images)

Mental health is notoriously difficult to categorize or define. After more than two centuries of dedicated study, we are scarcely any closer to achieving satisfactory explanations — scientific or otherwise — for the various forms of mental distress and disturbance that people can experience.

Compounding the difficulty of getting to grips with psychological suffering is the fact that social and personal adversity — such as poverty, inequality, economic precarity, and experiences of violence or abuse — significantly influence our mental health. And yet the experience of similar travails impact individuals and their mental health differently. Why do some survivors of war develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and not others?

Driven by a humanistic desire to alleviate suffering, and a justified deep-seated suspicion of its ideological justifications, leftists have understandably sought to find explanations of mental illness in the quotidian miseries of capitalist societies. Economic precarity and low incomes alone can’t explain depression — not everyone who lives on a low income is depressed, and not everyone with depression has a low income. Other forms of mental disturbance, like mania or psychosis, are even more difficult to solely attribute to issues of economic justice. Still, barring some modest scientific advances around social and genetic risk factors (in the case of schizophrenia) we are far from understanding their cause.

It is difficult to broach these questions of causation when the very issues we are trying to explain are so tenuously defined. Diagnostic labels attempt to impose order on a great diversity of experiences that we are simply unable to account for. Some people with schizophrenia hear voices and continue to lead rich and meaningful lives. Others experience debilitating and, at times, violently disturbing hallucinations or profound disorganization of thought and speech. Such individuals may be severely limited in their ability to complete the most basic everyday tasks. A combination of psychotherapy and antipsychotic medication can temper distressing features of psychosis in some, but not all, cases. For an unfortunate few, pharmacological side effects can be severe enough that they outweigh expected benefits.

In order to attend to any human ailment with appropriate compassion and suitability of treatment, we require some shared understanding, however broad, of the nature of the problem we seek to address. Many of the well-meaning criticisms of the medical profession’s treatment of psychological suffering have focused exclusively on its social causes, closing off the possibility of a rapprochement between a socialist critique of capitalist society and a scientific attempt to remedy unnecessary misery.

The Controversial Nature of Psychiatry

By and large, we have assigned the twin tasks of understanding and responding to mental suffering to psychiatrists. If not the most scientifically primitive area of modern Western medicine, psychiatry is easily the most polarizing. A study of psychiatry’s history will present bewilderingly divergent depictions of the profession. In its two-hundred-year history, psychiatry has undergone many periods of crisis and reinvention — and, with each transformation, new paradigms, evidentiary standards, and research methods emerge.

Mental health is defined not by how well an individual can adapt to their society but by how well society adjusts to the needs of its people.

Whether one is a proponent or critic of the discipline, the ever-shifting identity of psychiatry poses a significant challenge to anyone trying to weave a coherent narrative of its institutional and intellectual history. Advocates contend that psychiatrists are stubborn idealists or beleaguered soldiers of medical science. The field’s high-profile scandals, failed reforms, grand pronouncements, and public defeats are all stages along the familiar scientific path of incremental progress.

Critics, on the other hand, depict the discipline’s history as rife with startling violence. From this view, psychiatry is characterized by repression and conspiracy — psychiatrists are calculating agents who both benefit from and contribute to the punishment of those who threaten bourgeois morality and routine orderliness. And yet across these deep schisms of disagreement, one finds a fragile consensus connecting psychiatry’s apologists and many of its critics: madness continues to evade our basic comprehension.

Critics of the status quo approach to mental suffering have offered valuable objections to our most cherished assumptions about what constitutes mental illness. More importantly, they have drawn crucial attention to serious issues of moral and scientific integrity in the field.

On the Left, common criticisms seek to explain how psychiatry can inadvertently medicalize injustice. These criticisms highlight the incriminating relationship of interdependence between psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry and the ways in which psychiatry can be used to legitimize violence and social oppression. Critics such as Michel Foucault, R. D. Laing, and David Cooper have brought an invaluable political lens to bear on issues of diagnosis, treatment, and detention. They have, however, also given succor to the view that further interventions that target mental suffering are either misguided, futile, or inhumane.

Capitalism Is the Disorder, Mental Illness Is the Symptom

The intimate links between social inequality and mental suffering are well documented, and understood by liberals and leftists alike. The New York Times, the Financial Times, and Canada’s Globe and Mail have linked rising rates of depression, anxiety, and “deaths of despair” to defective social safety nets and woefully underfunded or severely inaccessible health care systems. Leftists, on the other hand, have long highlighted the structural tension between social welfare programs and the basic functioning of capitalism. The systematic privileging of accumulation over human need ensures that nothing — including care work — can take precedence over the imperatives of commodification and profit.

If poverty, exploitation, and alienation are inherent features of capitalism, the degradation of physical and mental health is inevitable as long as we continue to live under the domination of the market. For some, both episodic and chronic feelings of sadness, anxiety, and stress are best understood as logical responses to the structural forces at play in everyday life under capitalism.

Psychiatric medicine can function to legitimize and enforce the interests of the ruling elite either by default or design. As the late great Mark Fisher once wrote: “The current ruling ontology denies any possibility of a social causation of mental illness. The chemico-biologization of mental illness is of course strictly commensurate with its de-politicization.” This view, it must be said, is held by some psychiatrists and clinical mental health professionals themselves. Regardless, the general sentiment behind it is right: when political suffering is medicalized as personal dysfunction, our sense of social solidarity and collective political power also suffers.

In The Sane Society, the Marxist philosopher Erich Fromm attempts to offer a corrective formulation to the mainstream medical paradigm of mental health and illness. For Fromm, mental health is defined not by how well an individual can adapt to their society but by how well society adjusts to the needs of its people. A healthy society is one in which people have the means, freedom, and security to flourish as individuals while feeling solidarity and belonging as part of a greater whole. The corrosive ethos of competition and atomization of life under capitalism gnaws at our collective psyche and no one, not even the ruling class, is spared from its production of existential misery.

Efforts to expose the socioeconomic foundations of mental suffering typically take as their case studies mental states where the lines between health and illness are not easily differentiated. Depression, anxiety, existential dread — or “mood and anxiety disorders” — are as prevalent as they are different in degree. The near impossibility of drawing causal connections between concrete social phenomena and ill-defined mood and anxiety disorders is one of the limitations of socioeconomic explanations of mental illness.

It’s doubtful that all forms of mental suffering and disorganization — like psychosis — can be equally and satisfactorily explained by the miseries of life under capitalism (though one can easily see how they might be made worse). Discussions of the degree to which socialism could be a panacea for depression, anxiety, and trauma — especially those that are more chronic and severe — are mostly speculative. It seems more reasonable to presume that just as sorrow would exist in a postrevolutionary world, so, too, would mental illness.

Popular discussions of psychiatry often attribute to the profession an unnuanced understanding of our psychic life. One can certainly find neurobiological zealotry in the pharmaceutical industry and certain corners of the field. However, over the last two decades, the “biopsychosocial model” has emerged as the mainstream paradigm of contemporary psychiatry. It represents a significant shift in how the complex interplay between social factors, psychological development, and genes are taken into account by mental health clinicians.

Nevertheless, there are important criticisms regarding the applicability and coherence of the biopsychosocial model. Chief among these is that the model has no systematic framework for prioritizing between biological, psychological, and social factors. This leaves ample room for clinicians to ignore or overstate the importance of particular determinants and, in so doing, significantly impact care delivery.

History is rich with examples of how psychiatry has pathologized political resistance, dismissing acts of opposition as cases of mental disorder.

As an example, consider the hypothetical case of someone who is experiencing extreme distress due to their belief that powerful and malevolent spirits are trying to take control of their body. When interpreted through a narrow biological lens, their suffering might be attributed to poorly treated schizophrenia — it follows that finding a more effective antipsychotic medication would be the best course of action. A different physician, however, exploring this patient’s developmental history, might find a history of childhood abuse at the hands of a respected member of the patient’s faith community. Insofar as the patient’s current experience is rooted in psychological trauma, a psychotherapeutic intervention might be prioritized over medication trials. Yet another physician might explore both biological and psychological elements, but give further consideration to the patient’s social environment. If, for example, this patient resides in a dingy, violent, and chaotic boarding home, clinicians are far less likely to address the barriers that prevent them from pursuing psychotherapy, remembering to take their medication, and building trusting relationships.

Clinical case formulation is one of many areas in which a political analysis, guided by social and economic justice, is still sorely needed to avoid the kind of psychiatrization of daily life with which Fisher, Fromm, members of the Critical Psychiatry Network, and many others are rightly concerned. However, advancing a critique of the overreliance of psychiatry on chemical explanations of human suffering should not close off the possibility of investigating its biological causes.

Major Repressive Disorder: Madness and Social Control

Mental illness has assumed many different names, meanings, and definitions throughout history. Descriptions of “lunacy” and “melancholy” date back to antiquity. Because understandings of “madness” appear to be historically contingent, the very concept of mental illness is contentious.

Few thinkers have been as influential in constructing a theoretical scaffolding for madness as Michel Foucault. Madness and Civilization (1988), Foucault’s historico-philosophical analyses, traces the emergence of “madness” as a subject of scientific study and as a social phenomenon requiring state intervention and control. In his account, developing a “mental science” of madness — i.e., psychiatry — had nothing to do with deepening our understanding of human nature, and everything to do with new modes of governance. On this view, sciences of the mind are themselves structures of control — a “monologue of reason” drowning out all voices that threaten ruling-class authority or the social order.

Foucault’s theory that rulers in the early modern and industrial periods viewed the mad as threats to the social order is dubious at best. Historians have found virtually no evidence to substantiate this idea, which we should view as conjecture. Nonetheless, Foucault’s account still has merit. His careful treatment of the political and cultural values associated with madness has extended welcome theoretical tools to “mad activists” and anti-psychiatry groups. His work also inspired generations of scholars and clinicians to question what we deem normal and why, and how deviant behaviors are turned into disorders that need fixing.

These are useful questions. History is rich with examples of how psychiatry has pathologized political resistance, dismissing acts of opposition as cases of mental disorder. To cite two examples: drapetomania, or “the disease causing slaves to run away,” is an appalling instance of diagnosis giving cover to egregious social practice, and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD, presently included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) is a diagnosis typically applied to children and adolescents who appear unusually hostile and are insufficiently obedient or deferential to adults in positions of authority. As many critics have pointed out, ODD is a value-laden and poorly defined diagnosis that risks medicalizing the environmental and contextual factors that shape childhood development and behavior. Yet another of psychiatry’s failings, as LGBTQ campaigns and movements have shown, is the way in which sexual orientation and nonnormative expressions of gender have been targeted by medical pathology in unspeakably harmful ways.

However, arguments that equate psychiatry with almost dictatorial social control present a reductive understanding of the profession and credit psychiatrists with far more power than is warranted. Absent in these narratives is a vision of patients as recipients of care rather than victims. How then are we to make sense of present and former patients who report positive and, in some cases, life-changing outcomes following psychiatric treatment? Not only does the victimhood and survivorship view discount some people’s experiences of healing — it also suggests that people need only be freed from the vice grip of psychiatry to flourish.

Taken to their logical end point, social control theories — those that are broadly termed “anti-psychiatry” — argue that mental illness is a myth. This is a deeply contentious proposition, especially for boots-on-the-ground mental health workers, or anyone who’s ever experienced or observed someone struggle with debilitatingly obsessive behavior, incomprehensibly horrific visual and auditory disturbances, or radically out-of-character and dangerous decisions in the throes of a manic state.

For the most intransigent members of the anti-psychiatry movement, the myth of mental illness is an attempt by oppressive social strictures to foreclose on the revolutionary power of desire and deviance. The concept of the schizophrenic, for some French thinkers writing in the wake of the Paris uprising of May 1968, was a lodestar for the libidinal power that could remake society. Revolutionaries, according to this school of thought, could dismantle structures of hierarchy and oppression by embracing madness and desire. While the liberatory force of the mad or deviant individual may have failed to achieve revolutionary social change, the architects of neoliberalism deployed an ethos of radical individualism to considerable success. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were only too happy to give emphasis to a social order premised on self-interest and self-gratification.

Historically, those who deny the existence of mental illness have found strange bedfellows in right-wing politicians. The Right, eager to justify the abdication of responsibility for publicly funded and humane mental health supports, is only too happy to trade on psychiatry’s manifest wrongs. In Canada and the UK, deinstitutionalization — the historic process of dismantling the asylum system toward community-based care — unfolded with the explicit aim of reducing health care expenditures.

Historically, those who deny the existence of mental illness have found odd bedfellows with right-wing politicians.

Over recent decades, community-based mental health services and supports have developed through a process of path dependency, without coherent plan or vision. The feeble networks of private, charity-based, and government services that now form the basis of community care across much of the United States and Canada are unable to provide continuous care to many people struggling with severe mental illness. The lives of those suffering from mental illness are often marked by violence, poverty, homelessness, and incarceration. Anti-psychiatry activists characterize psychiatry as a component part of this domination to claim that it does more harm than good, thereby advocating the eschewal of treatment. At what point does the struggle against social control align with a politics of social neglect?

The Pharmaceutical-Industrial Complex

The influence of the pharmaceutical industry over medical education, clinical research, and clinical practice is not unique to psychiatry. However, it is true that psychiatry’s role in impeding a thorough understanding of the very conditions the pharmaceutical industry’s drugs purport to treat is disturbing. Pharmaceutical companies exert a troubling degree of power and authority in defining mental disorders, conducting research into the causes of mental suffering, and determining how it can best be addressed.

In the mid-twentieth century, as psychiatry became increasingly reliant on pharmaceutical interventions, the pharmaceutical industry recognized how profitable an alliance could be, and a relationship of disquieting dependency was born. In Anatomy of an Epidemic (2010), Robert Whitaker traces psychiatry’s struggle for legitimacy alongside the interests of the pharmaceutical industry to expose the deep links of dependency between them. This relationship, following the emergence of “breakthrough” psychoactive drugs in the 1950s, is clearly illustrated by the transition from talk therapy as the dominant method of treatment toward pharmaceutically driven therapy.

Though initially developed to treat infections, drugs like Thorazine and meprobamate were found, rather serendipitously, to be helpful in altering mental states and blunting the presence of acute symptoms of psychosis, anxiety, and depression. Even though nobody knew how they worked, they rapidly gained widespread use in mental hospitals and outpatient settings.

Over time, researchers were able to observe that psychoactive drugs affected the balance of various chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) in the brain, and reasoned that the drugs must be correcting for chemical imbalances. For example, because Thorazine blocks dopamine receptors in the brain — the effect of which reduces aggression and psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations — it was postulated that psychoses must be caused by an excess of dopamine. From these kinds of observations, the infamous “chemical imbalance” theory of mental illness was born.

The following decades of research into the physiology of psychotic illnesses opened important lines of inquiry for understanding the neurobiological elements involved in mental distress and disturbance. The trouble with all this research, however, is the same problem inhibiting most psychiatric groundwork and experimentation — it is largely controlled by pharmaceutical interests. Working within the matrix of market incentives, pharmaceutical companies make bold pronouncements and reductive claims about the causes of mental illness. The chemical imbalance theory was peddled to patients and the public because it was a convenient marketing tool. But its promise of chemical cures was greatly exaggerated.

Pharmaceutical companies have explicit means of selling their products — such as direct-to-consumer advertising — and more covert strategies. Industry lobbying has a significant impact on public health and drug policy, and corporate financing of academic activities and clinical research seriously biases medical education and clinical practice guidelines. By and large, psychiatry rests on a knowledge base that has been compromised by industry involvement, but this fact alone does not explain legitimate concerns over psychiatric overreach. Family physicians — who are responsible for the majority of psychopharmaceutical medications available to outpatient populations — receive far less training in psychotherapy than they ought to. Their good-faith efforts to help people are often compromised by an overreliance on the prescription pad.

As prescribers continue to make use of crude psychopharmacological tools, research and development for novel psychopharmaceutical interventions has ground to a virtual halt. It’s far more profitable for companies to tweak, re-patent, and rebrand existing medications than it is to engage in the much riskier business of creating novel theories and treatments. This explains, in part, why pharmaceutical companies spend far more money on marketing than research and design.

It’s far more profitable for companies to tweak and rebrand existing medications than to engage in the much riskier business of creating novel theories and treatments.

Those who defend and promote psychopharmacology do so largely because its drugs, though imperfect, are generally effective. However, difficulties arise when appraising the truthfulness of the pharmaceutical company’s claims. The inordinate amount of pharmaceutical industry money involved in medical studies severely compromises the quality and trustworthiness of the information it makes public. The fact that studies with pharmaceutical industry funding are far more likely to report positive findings has been well documented. Furthermore, the drug approval processes of the US Federal Drug Administration and Health Canada — which generally follows decisions made in the United States — are dramatically skewed to the benefit of pharmaceutical companies.

In order to take a drug to market, drug companies must submit all the clinical trials they have sponsored (they are not obliged to submit independent reviews of their products). Although drug companies can run as many trials as they like, they only must produce two trials showing that a drug is more effective than a placebo for it to be approved. Negative trials rarely see the light of day, while the positive studies are promoted at conferences and published in medical journals. The public, and to some extent the physicians who treat us, are left largely in the dark.

Toward a Left Politics of Mental Care

It’s easy to cherry-pick from psychiatry’s conspicuous abuses in order to cast the entire field — past, present, and future — in a negative light. It should be noted, however, that defenders of psychiatry have also been able to produce their own selective histories that cast a far less negative light on their discipline. A more evenhanded approach would be to maintain our criticisms of psychiatric medicine while recognizing the profoundly difficult task of responding to mental suffering.

Prominent figures in the field like Leon Eisenberg and Allen Frances have offered very public appraisals of psychiatry’s chronically limited capacities and its many failures. In 1982, amid the frenzied promises of a “neurobiological revolution” in psychiatry, Roberto Mangabeira Unger highlighted the discipline’s challenges in a stirring address to the American Psychiatry Association:

Nothing harms science more than the denial or the trivialization of enigma. By holding the explanatory failures of psychiatric science squarely before our eyes, we are also able to discover the element of valid insight in even the most extreme and least careful attacks on contemporary psychiatry: to make even his most confused and unforgiving critics into sources of inspiration is a scientist’s dream.

Science is far from politically neutral, but the Left can and must employ its methods to advance emancipatory and transformative political ends.

There are several dimensions to the politics of mental suffering. We know that people are enduring significant mental distress that can be reduced or resolved. However, we lack satisfying sociological, psychological, and biological explanations for the diverse forms of mental distress and disturbance that people can experience. Psychiatrists do not have a monopoly over this state of ignorance — we all share it. But we have ceded significant authority and power to physician researchers and pharmaceutical companies to advance our public understanding over matters of great concern and complexity. Further study must be held to higher standards of transparency and democratic accountability.

Care work is an important part of the broader fight to win universal social and economic freedoms. The public provision of thoughtfully designed social and therapeutic programs — such as clubhouses, peer groups, supportive housing, case management, and truly accessible psychological and medical therapies — are desperately needed to support people to live safely and well.

Wresting power from the corporations and institutions currently profiting off their monopoly over mental suffering is neither easy nor straightforward. The road to democratizing scientific research is sure to be an uphill battle. Nevertheless, it is critical that we move beyond censure and wholesale rejection of psychiatry toward a more active engagement with these issues. This begins with humility and a nuanced appreciation of the epistemological and political challenges we face.

A left politics of mental care must call for publicly funded and democratic inquiry into the nature of mental suffering and possible treatments, ongoing assessments of what is important to people who suffer, and a commitment to provision of treatment and solicitude in care. Societal responses to mental illness have long been characterized by extremes of paternalism or neglect. The Left has much to contribute to forging a new path.

Collapses of local junk bond prices signal that even tougher times lie ahead

This week, 27 foreign policy experts called for a no-fly zone in Ukraine that would lead to the shooting down of Russian planes — an idea that could lead to a nuclear holocaust. Their message is being bankrolled by arms manufacturers and fossil fuel interests.

An F-15E Strike Eagle flies in the US Central Command “area of responsibility” on January 27, 2021. (Staff Sgt. Sean Carnes / US Air Force via Wikimedia Commons)

In spite of its immense danger, the campaign for a “no-fly zone” in Ukraine seems to be gaining momentum, with twenty-seven foreign policy luminaries signing a letter earlier this week calling on the Joe Biden administration to set up a “limited” one over the country, to protect the humanitarian corridors recently agreed to in Russia-Ukraine talks. The letter has already been widely cited in the press, giving the disastrous idea more legitimacy.

What you won’t be told about is the behind-the-scenes role of weapons manufacturers, fossil fuels, and certain oligarchs in promoting these views.

A no-fly zone is a deviously clever euphemism for war, involving the shooting down of Russian planes and destruction of Russian air defenses. As soon as US forces destroy a Russian aircraft, killing its pilot, it would turn Moscow’s invasion from a regional war to something closer to the scale of a world war — only this time involving stockpiles of hundreds and thousands of nuclear weapons, which didn’t exist when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland. Even a hawk like Marco Rubio says as much in opposing the idea.

Given this outcome, it’s perhaps not surprising that numerous names on the letter are either financially intertwined with the defense industry or work for organizations funded by it.

Ian Brzezinski had a five-year stint as a principal in Booz Allen Hamilton, a Pentagon contractor, before going to lead the Brzezinski Group, described as “a strategic advisory firm serving U.S. and international commercial clients in the financial, energy, and defense sectors.” John Kornblum is a senior advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a think tank that counts Northrop Grumman as one of its two largest corporate donors and that also receives donations from firms like General Atomics, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing.

Both Ben Hodges and Kurt Volker are part of the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), a think tank that in 2021 counted defense firms BAE Systems, General Dynamics, General Atomics, and Lockheed among its list of contributors. Volker is also the international managing director for and cochair of the advisory board to BGR Group, which “represents major defense and aerospace companies, aerospace suppliers, government service providers, non-profit organizations, and states and municipalities that have an interest in U.S. defense policy.”

Philip Breedlove serves on the board of advisors of the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), a hawkish liberal think tank that has been used to staff Democratic administrations, including this one. Besides the Pentagon, Northrop Grumman is CNAS’s top donor, with Raytheon, Palantir, BAE, Boeing, Booz Allen, Lockheed, and General Dynamics in lower tiers of contributors.

Evelyn Farkas, meanwhile, is a former Pentagon official and national security analyst who heads the somewhat mysterious Farkas Global Strategies, which describes itself vaguely as working for “strategic growth at some of the largest corporations around the world.” Farkas’s page describes her as “leveraging technology companies’ capabilities to improve key defense acquisition programs,” and lists “operational resilience, risk mitigation, cybersecurity, [and] critical infrastructure protection” as some of her expertise, possibly hinting at the kind of work the firm does.

Farkas is also on the board of directors of the Project 2049 Institute, which pushes for a more confrontational stance toward China and upping military sales to Asian countries in tension with it. While it no longer displays its donors, an archived page lists several of the weapons manufacturers named previously, as well as private military contractor DynCorp (later bought by Amentum), defense firm Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), and SBD Advisors, which “focuses on identifying and connecting private sector innovation to meet national security challenges.”

It’s an important reminder of the way that, in Washington, foreign policy and private financial interests tend to conveniently overlap. Lockheed and Raytheon executives had lamented the impact on their bottom line of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan last year, and they and General Dynamics had celebrated the business opportunities coming from the current and entirely avoidable geopolitical tensions with China. In January of this year, they were positively salivating over the rising tensions over Ukraine, and there’s now talk of rebranding weapons-manufacturer stocks as “socially responsible” investments in light of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s invasion.

This is how the modern version of the military-industrial complex that President Dwight Eisenhower talked about works. Certain companies have a vested interest in war and conflict; they lavishly pay and promote voices that favor policies that would create more of it; those voices cycle through government positions, corporate-funded think tanks, and their own business ventures trading off that experience, raising their prominence further; so when the opportunity for more war comes, there is always a bench of high-profile, credentialed hawks instinctually ready to make the public case for more war.

Ten of the signatories hold various positions at the Atlantic Council, a hawkish think tank funded by a cornucopia of business interests, while another was a senior fellow there for six years. The Atlantic Council has its share of military-industry donors, as well as various NATO governments and NATO itself, but two other sources are of special interest: System Capital Management (SCM) and the Victor Pinchuk Foundation.

Pinchuk and Rinat Akhmetov, the head of SCM, are two of the richest men in Ukraine. Some of the country’s oligarchs, including Akhmetov, had initially fled the country when Moscow’s invasion began but soon returned to rally together against the war, in spite of preexisting conflicts and tensions with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. According to Forbes, the value of the oligarchs’ assets had fallen sharply in the separatist-controlled regions and around the country in the lead-up to the war.

“They realized that Putin presents a clear threat to all of Ukraine, and their assets as well,” Ukrainian analyst Taras Berezovets told Forbes. He added that Akhmetov’s assets are especially in danger, since “the majority of his factories and assets are located in Mariupol and Dnipro.” It’s important to note Akhmetov has significant business interests in Russia, too.

Pinchuk, meanwhile, has been a major donor to the Atlantic Council for years and sits on its international advisory board. It is just one of many pro-Western and pro-NATO initiatives Pinchuk has funded over the years. He also recently commissioned a survey backing greater support for Ukraine against Russia and in the lead-up to war had “hosted a lot of off-record meetings with Western officials to persuade them to get more assistance to Ukraine,” Berezovets told Forbes. (Pinchuk is also a donor to CEPA).

Besides the two oligarchs, there is another major business interest funding both the Atlantic Council and some of the other entities with whom the letter’s signatories are aligned: fossil fuel. Oil companies like Crescent Petroleum, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, Chevron, Mubadala Petroleum, and Exxon litter the list of its donors, along with the oil magnate–founded Charles Koch Institute.

War is big business for fossil fuel companies, with the Pentagon the world’s largest institutional consumer of petroleum. In a world that continues to drag its feet on transitioning to an energy source that won’t eventually kill us all, fighter planes, tanks, military vehicles, and the like overwhelmingly run on fossil fuels, as do the vehicles that transport tens of thousands of soldiers to fight in far-off countries. And that’s not even getting into the fossil fuels needed to manufacture all these things.

It’s no surprise, then, that CSIS also counts BP, Chevron, Exxon, and Saudi Aramco as major donors. The McCain Institute, where signatory Claire Sechler Merkel is senior director of Arizona programs, has among its donors Chevron, MEG Energy, and BP, as well as the Saudi embassy and Raytheon. CNAS counts BP, Exxon, and the Charles Koch Institute among its contributors.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic Council, CEPA, and the Project 2049 Institute all also list the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) as a funder, while Daniel Fried, another signatory, sits on its board of directors.

The NED, a benign-sounding entity whose creator has said does the work that “was done covertly twenty-five years ago by the CIA,” has played an important role in the tit-for-tat game of political meddling between Russian and the United States this century, which has heightened tensions between the two countries. It was this back-and-forth that culminated in Moscow’s involvement in the 2016 US election, which was reportedly Putin’s revenge for the actions of entities like NED in Russia and elsewhere earlier that decade. The NED had a big part in stoking the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, for instance, which played an important role in the chain of events that led to this current war.

Finally, it’s worth noting that several of the signatories were directly involved in NATO policy that has sowed the seeds for this conflict. Brzezinski played a key role in expanding NATO under George W. Bush, while Barry Pavel led defense planning for the first round of NATO expansion under Bill Clinton. Alexander Vershbow, meanwhile, “was centrally involved” in “transforming NATO and other European security organizations to meet post-Cold War challenges” — in other words, transforming NATO from a defensive alliance to an offensive one fighting several wars that had nothing to do with defending Europe against foreign attack, a key part of why the Russian establishment, not just Putin, views the alliance as threatening.

Needless to say, the above isn’t a justification for Putin’s criminal and increasingly destructive war. Rather, these are points that have been made by numerous establishment foreign policy experts over the decades as underlying factors that led us to this point, the same way that the Treaty of Versailles, despite its authors’ intentions, laid the groundwork for World War II. So besides the financial interests involved here, there’s also the factor of individual judgment: some of the same people who helped bring us to this mess are now urging another potentially disastrous policy.

The only way to end this war without prolonging the suffering of Ukrainians or sparking global destruction is a political settlement between Russia, Ukraine, and the United States and the European Union. Unfortunately, that doesn’t sound nearly as sexy or viscerally satisfying as a shooting war, and it means a lot of wealthy, powerful people won’t be able to make a lot of money.

The false narrative of rampant voter fraud defouling US elections has been around for decades. But fueled in large part by Donald Trump’s persistent lies about the 2020 presidential election, which he lost, the myth of voter fraud appears to continually be reaching an apotheosis, only to pass it.

Now, enter another dystopian turn: Election cops. The country’s first election police force is poised to make its debut in Governor Ron DeSantis’ Florida.

The state’s GOP-controlled legislature on Wednesday approved a bill that includes a measure to create the “Office of Election Crimes and Security,” which will hire election investigators that aren’t sworn officers of the law, in order to crack down on voter fraud at the ballot box. According to CNN, the squad will have the power to launch independent investigations “into allegations of election law violations or election irregularities in this state.” Voting organizations found in violation of Florida’s already stringent election laws will have their fine caps increased from $1,000 to a staggering $50,000.

Critics say the plan is a recipe for disaster that’s all but certain to intimidate voters and suppress the vote. But it’s also a curious one for DeSantis, considering his own praise for how the 2020 election was conducted. “The way Florida did it, I think inspires confidence, I think that’s how elections should be run,” the Florida Republican had said at the time. Only three instances of voter fraud were identified in the state—and two of the cases involved registered Republicans.

But as my colleague Ari Berman has reported, the exceedingly low instances of voter fraud haven’t stopped the GOP, let alone DeSantis, from adopting extreme voting measures around the country. Thanks to DeSantis, who is widely expected to run for president, we can now add an election police force to the list.

Northeast Ohio’s Cuyahoga River bisects the city of Cleveland, winding its way past parks, railyards, and downtown breweries before emptying out into Lake Erie. The waterway has come a long way since 1969, when the river’s polluted waters caught fire and brought national attention to the nascent environmental movement. Today, people fish in the river, stroll along its banks, and enjoy paddleboarding festivals. But several dozen times a year, heavy rains flood the waterway with raw sewage.

Like many older cities in the Midwest and Northeast, Cleveland’s sewer and stormwater systems are combined, and too often can’t handle the volume of water coursing through them after a heavy storm. The city is a little over halfway through an effort to upgrade this network, building tunnels to store extra wastewater deep underground. But there’s a problem, experts warn: The designs are based on decades-old rainfall estimates that do not reflect current – let alone future – climate risk.

That worries Derek Schafer, executive director of the West Creek Conservancy, a local nonprofit that aims to protect Cleveland’s watershed. “Flooding is natural,” Schafer told Grist. But now, “with a changing climate system, we have higher volumes at quicker intervals, so our systems become even more quickly inundated.”

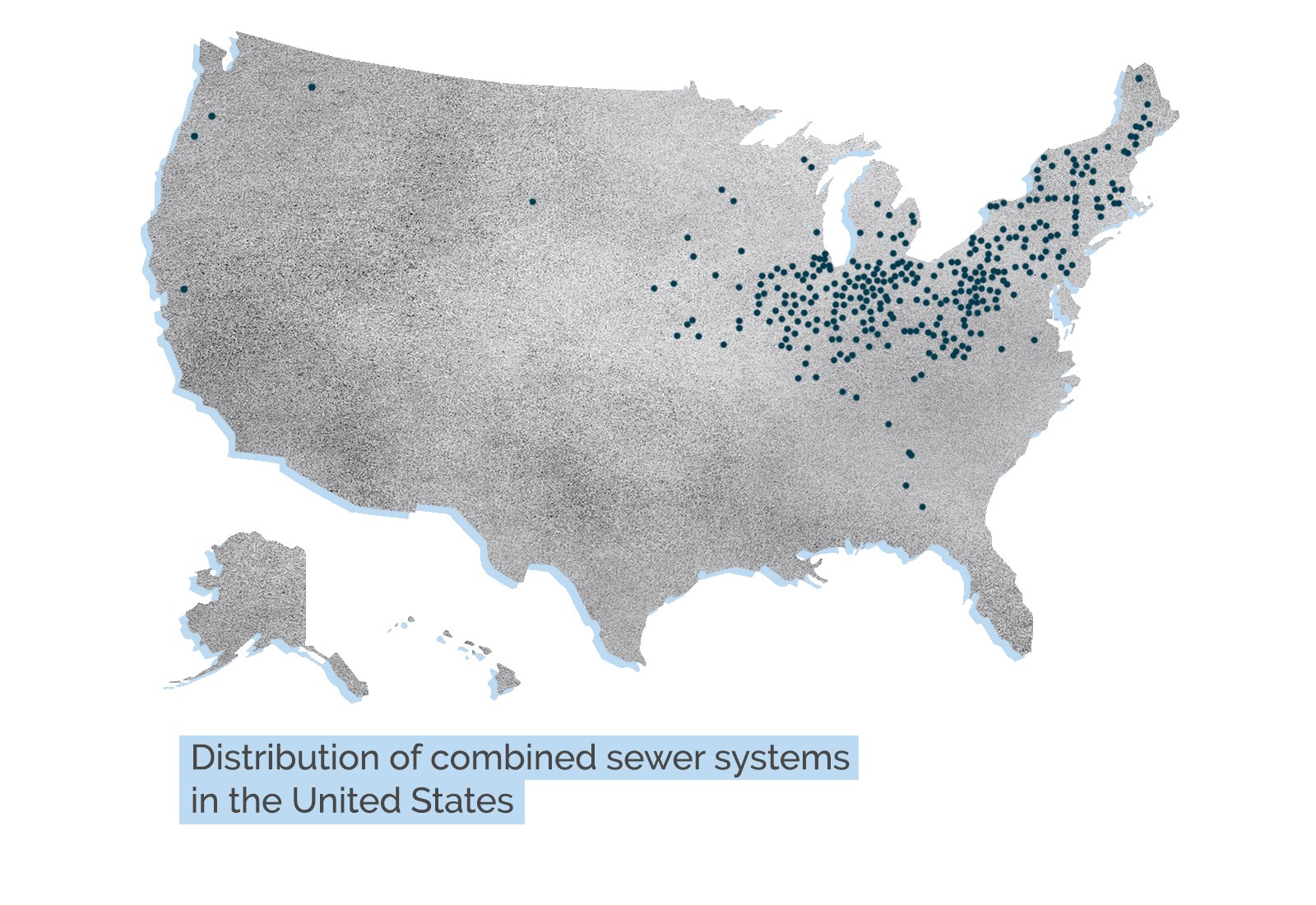

Today, combined sewer systems like Cleveland’s are found in more than 700 communities around the country. In 2004, the last year for which federal data is available, they collectively released 850 billion gallons of raw sewage into rivers, streams, and lakes — closing beaches, polluting drinking water sources, and contributing to harmful algae blooms. The Midwest is home to 43 percent of these systems, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

As of 2004, more than 700 communities around the U.S. had combined sewer systems, where wastewater and stormwater flow through the same pipes. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

As of 2004, more than 700 communities around the U.S. had combined sewer systems, where wastewater and stormwater flow through the same pipes. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection AgencyGrist

Spilling large amounts of sewage into waterways is a direct violation of the Clean Water Act. And many cities, from Detroit to Chicago, have been forced to sign consent decrees with the EPA, requiring them to reduce the number of overflows by upgrading water infrastructure and capacity. This process, however, can take decades from planning, funding, and permitting to completion, said Becky Hammer, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council who focuses on federal clean water policy. That means the rainfall estimates that dozens of cities use to design their billion-dollar projects are already obsolete by the time they’re finished. The government’s own rainfall estimates are also outdated — it last released figures for Ohio, for example, in 2004 — making planning difficult even if updates were required.

Youngstown, Ohio finalized a $160 million long-term control plan for sewage overflows in 2015 based on rainfall data from the early 1980s. It’s currently in the second phase of its plan, which involves constructing a “wet-weather facility” to store and treat excess sewage and stormwater during periods of heavy rain. Indianapolis is halfway through a $2 billion tunnel project that was designed more than 20 years ago, using precipitation estimates from 1996 to 2000. Chicago is in the final stage of a nearly $4 billion effort to construct 109 miles of tunnels and three reservoirs that was designed in 1972, then updated based on modeling conducted in 2012.

Now, climate change is setting these infrastructure projects even further behind. In the decades since cities’ plans were first approved, storms in the Midwest have grown more frequent and intense. Total annual precipitation in the Great Lakes region has increased by 14 percent, according to research from scientists at the University of Michigan, and the amount of rainfall from the heaviest storms has grown by 35 percent.

A man tries to unplug a sewer drain in a suburb of Chicago following heavy rains in July 2017.

A man tries to unplug a sewer drain in a suburb of Chicago following heavy rains in July 2017.Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

The EPA doesn’t instruct cities to consider climate change projections in their proposals, despite a report from the agency finding that “many systems could experience increases in the frequency of [sewage overflow] events beyond their design capacity.” A provision that would have required projects receiving federal funding to conduct climate change assessments was struck from the bipartisan infrastructure bill before its passage last year, Hammer said.

“There are thousands of people [with] sewage and floodwater either backing up into their homes, or running off streets into their basements, damaging property and threatening their health,” Joel Brammeier, president of the nonprofit Alliance for the Great Lakes, told Grist. It is a “failure to modernize our water infrastructure to deal with the reality that people are facing across the Midwest.”

The issue is gaining new urgency with an infusion of federal funding from November’s bipartisan infrastructure bill expected to hit state coffers in the coming months. Though cities haven’t yet figured out exactly how they’re going to use the funding or how much they’ll receive, the package includes $55 billion for water, wastewater, and stormwater management over five years. Biden’s proposed Build Back Better bill, which is currently stalled in the Senate, also includes $400 million per year directly to deal with combined sewer systems.

Cleveland started the overhaul of its water infrastructure system in 1994 under the federal Combined Sewer Overflow Control Policy, and work got underway after signing a consent decree with the EPA in 2010. The $3 billion initiative, known as Project Clean Lake, was designed using rainfall data from the early 1990s. The project’s seven new tunnels — three of which are complete, with another operational next year and three others in the construction and design phases — are built to capture most of the runoff from the “largest-volume storm” in a “typical year,” which would dump 2.3 inches of rain in 16 hours, said Doug Lopata, a program manager for the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District.

Since Cleveland began planning Project Clean Lake, however, climate impacts have gotten worse. In September 2020, Cleveland received nearly four inches of rainfall in 24 hours, the third-highest total for a single day in the city. Half of the top ten rainfall days in the city have occurred since 2000, with more than 3.5 inches of rain falling in a day in 2005, 2014, and twice in 2011. Looking ahead, more intense rainfall in the 21st century “may amplify the risk of erosion, sewage overflow, interference with transportation, and flood damage” in the Great Lakes region, Michigan researchers found.

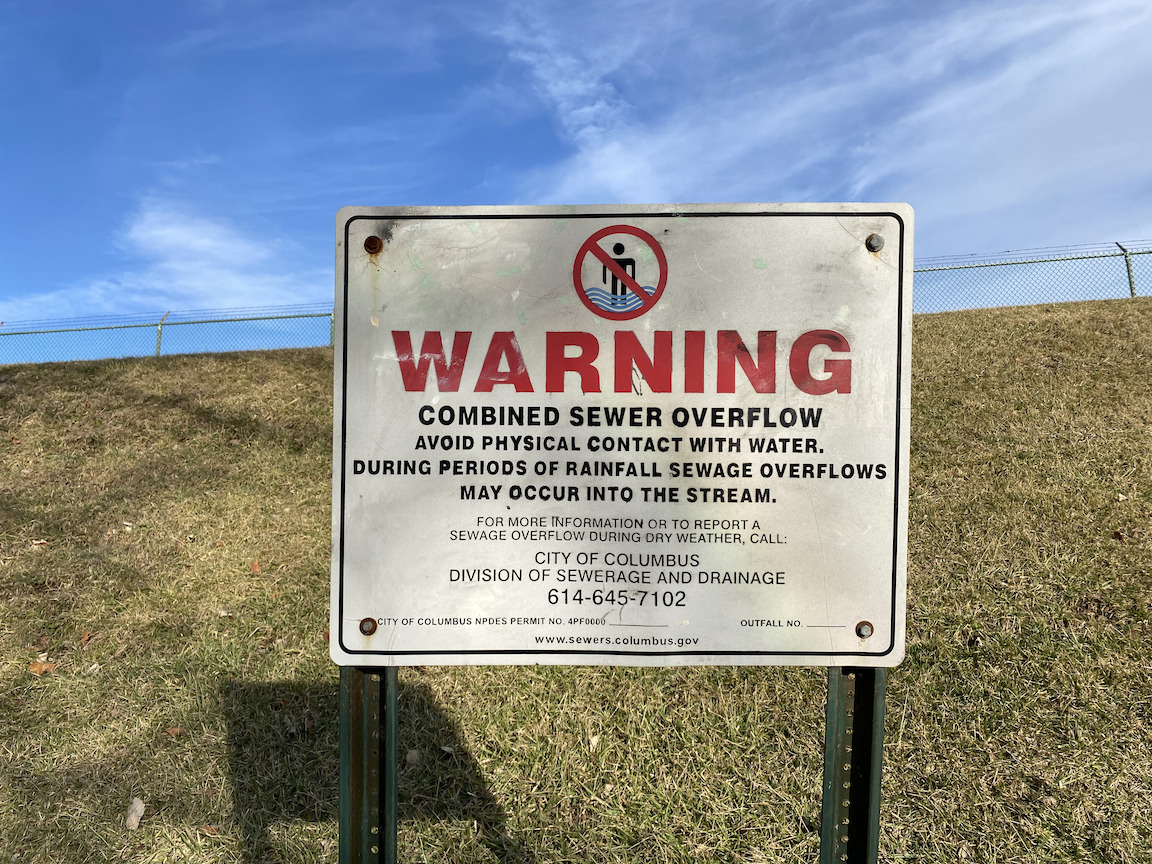

A sign warns of a combined sewer overflow, a point where sewage and rainwater discharge into the Olentangy River in Columbus, Ohio. Diana Kruzman/Grist

A sign warns of a combined sewer overflow, a point where sewage and rainwater discharge into the Olentangy River in Columbus, Ohio. Diana Kruzman/GristDespite these changes, Lopata said the sewer district isn’t planning to change the structure or design of Project Clean Lake, which aims to capture 98 percent of the water that would otherwise result in sewage overflows. Lopata believes that goal will still be achieved, even as climate change stresses the system. And even if sewage overflows aren’t eliminated entirely, he said, they’ll be reduced enough to keep the sewer system in compliance with the EPA. However, Lopata also said the district is monitoring rainfall data from the past decade and conducting an internal study to learn more about how the “typical year” has changed.

Anticipating greater and more frequent rainfall doesn’t just mean building bigger tunnels to accommodate it, though. Brammeier said cities will have to implement more of what’s known as “green infrastructure” — restoring wetlands that can absorb water and removing impervious surfaces like asphalt to reduce the amount of water that ends up in combined sewer systems in the first place. That’s going to require “a new way of thinking about doing water infrastructure at a large scale,” Brammeier said.

“You can’t build a tunnel big enough to stop the impacts of climate change,” Brammeier said. “You’ve got to think about how we’re going to make our water [infrastructure] more resilient in a more integrated way than we’ve thought about it in the past.”

Some cities are waking up to that message. Project Clean Lake includes $42 million in green infrastructure investments, and Detroit developed a 15-year green infrastructure plan to replace a tunnel project that was canceled in 2009. Milwaukee, which completed its own “deep tunnel” in 1993, now aims to eliminate sewer overflows entirely by 2035, capturing 50 million gallons of runoff with green infrastructure alone.

Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) to deal with combined sewer overflows involves building three large reservoirs to hold extra wastewater during storms.

Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP) to deal with combined sewer overflows involves building three large reservoirs to hold extra wastewater during storms.Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

While these improvements are progress, they’re likely not enough to prepare for what’s ahead, Brammeier said, and that even agencies that invest in resilient infrastructure now will need money to maintain it. Detroit’s calculations for how much rainwater the system will capture are based on data only up to 2013, and the plan states that “climate change is ignored” in this modeling. Milwaukee, which commissioned a report examining the sewer system’s vulnerability to climate change in 2014, has yet to implement many of its recommendations, according to a 2019 assessment. The city acknowledged that “continued increases in rainfall intensities and amounts” due to climate change would make it difficult to meet its rainwater-capture goal consistently.

Without significant federal aid, the costs of dealing with sewage-laced flooding are passed on to ratepayers, many of whom can’t afford to pay higher water bills in the first place. The price of water in cities like Cleveland and Chicago has more than doubled over the last decade, according to an investigation by APM Reports. Despite these increases, though, low-income communities still experience the worst consequences of aging infrastructure, Hammer said — including flooded basements from backed-up sewers. That makes funding for climate resilience in these communities all the more urgent.

“The estimates for the nationwide need for wastewater and stormwater projects is in the hundreds of billions,” Hammer said. “So we are not done.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Cities are investing billions in new sewage systems. They’re already obsolete. on Mar 8, 2022.